School has started, and with it debate about people driving their kids to and from school is flaring up. And again people are questioning how much traffic is caused by this. As someone who bikes to school with his son every day I am keenly aware of the traffic mess around schools. But since I choose not to drive regularly, I don’t have a feeling for broader traffic patterns on non-school days to compare this too.

But who needs anecdata when we have actual data on this: counts from traffic light induction loops. While the City of Vancouver has been talking for more than a year to make this data available, Surrey has been at it for about a year now (big thanks!), and we have played with that data a while back. It seems however that the Surrey Open Data API changed since then and the interactive map from last year is not pulling in live data any more. Instead of updating the old map I thought my time is better spent in doing something new.

There are still lots of challenges when using loop counts for answering questions about school traffic, but it’s a great resource to ground the discussion on. But it is also a resource that I admittedly have not spent much time with, and that will need some work to better understand the data quirks and issues. But not better way to get started with this than doing an exploratory blog post!

Induction Loops

Most people will recognized induction loops as the circular (or rectangular) cutouts in the road close to the stop line of traffic lights that detect if cars are waiting to make a turn. The loops emit an RF frequency which will induce a current in nearby metal objects, e.g. a car sitting on top, which in turn will induce a magnetic field that will induce a current in the induction loop. Which enables the induction loop to detect the presence of metal objects: motor vehicles in most cases.

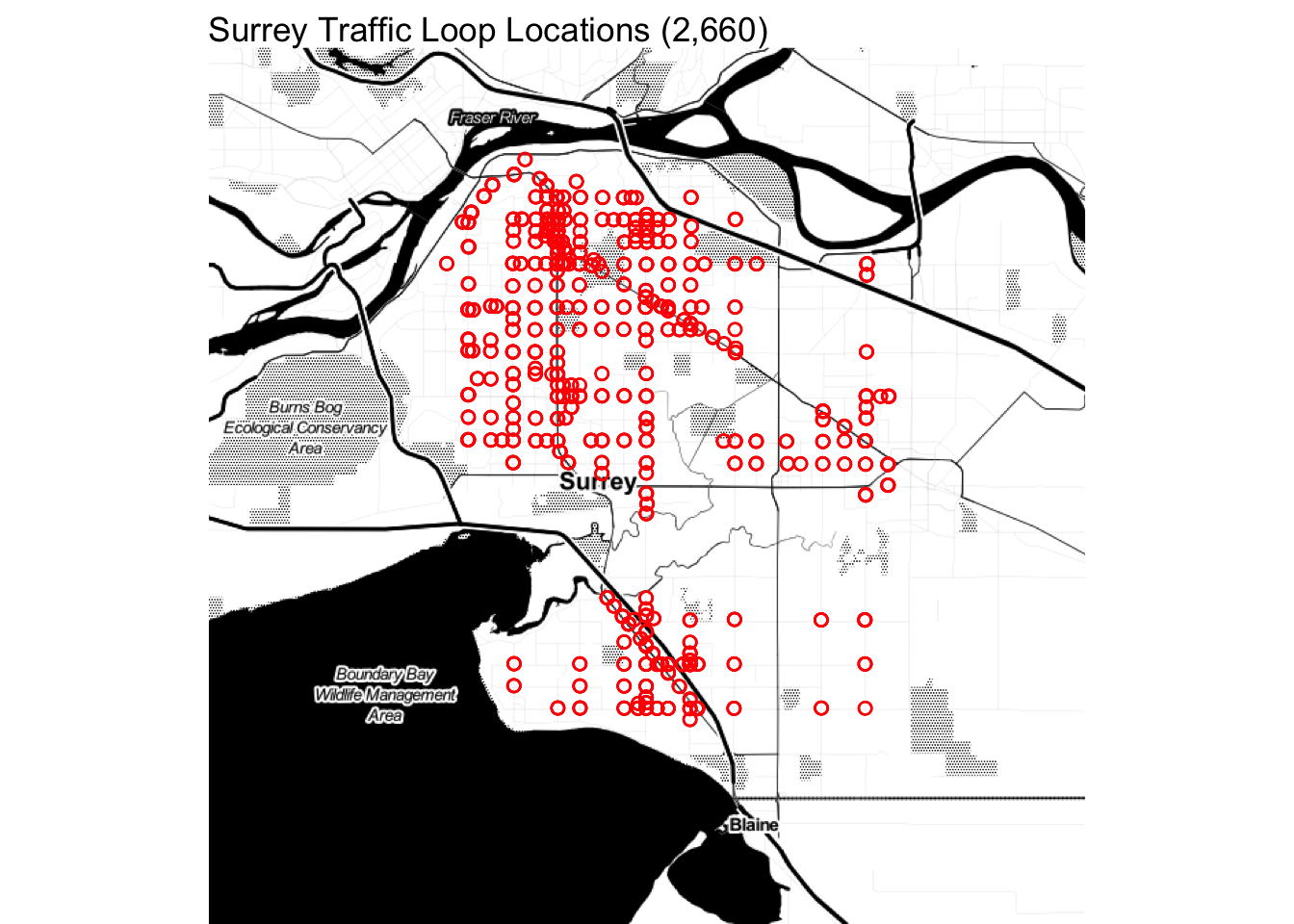

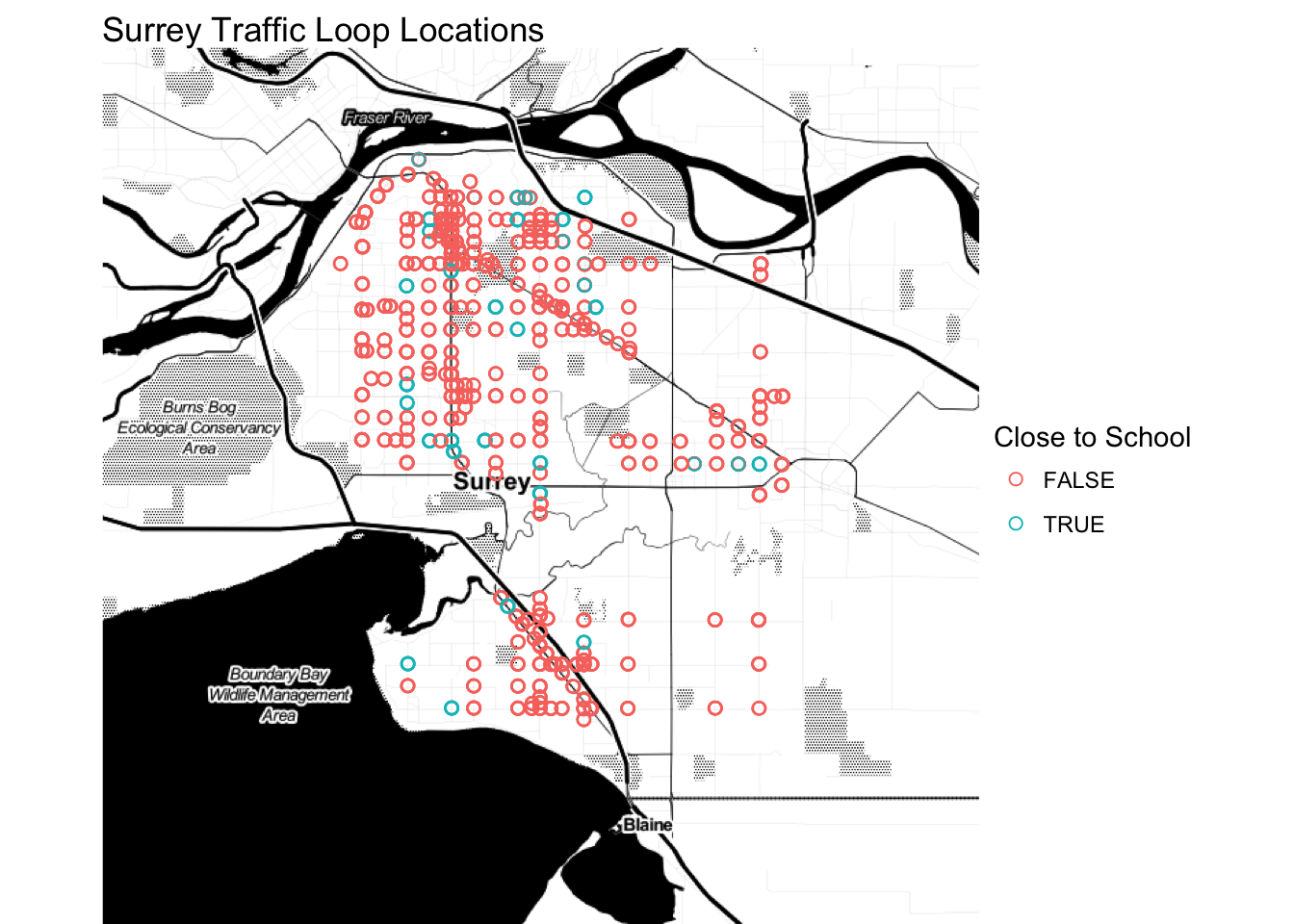

Surrey publishes (a selection of?) traffic loop counts on their Open Data website, about 1/3 of which have been geocoded so we know where they are.

Counts

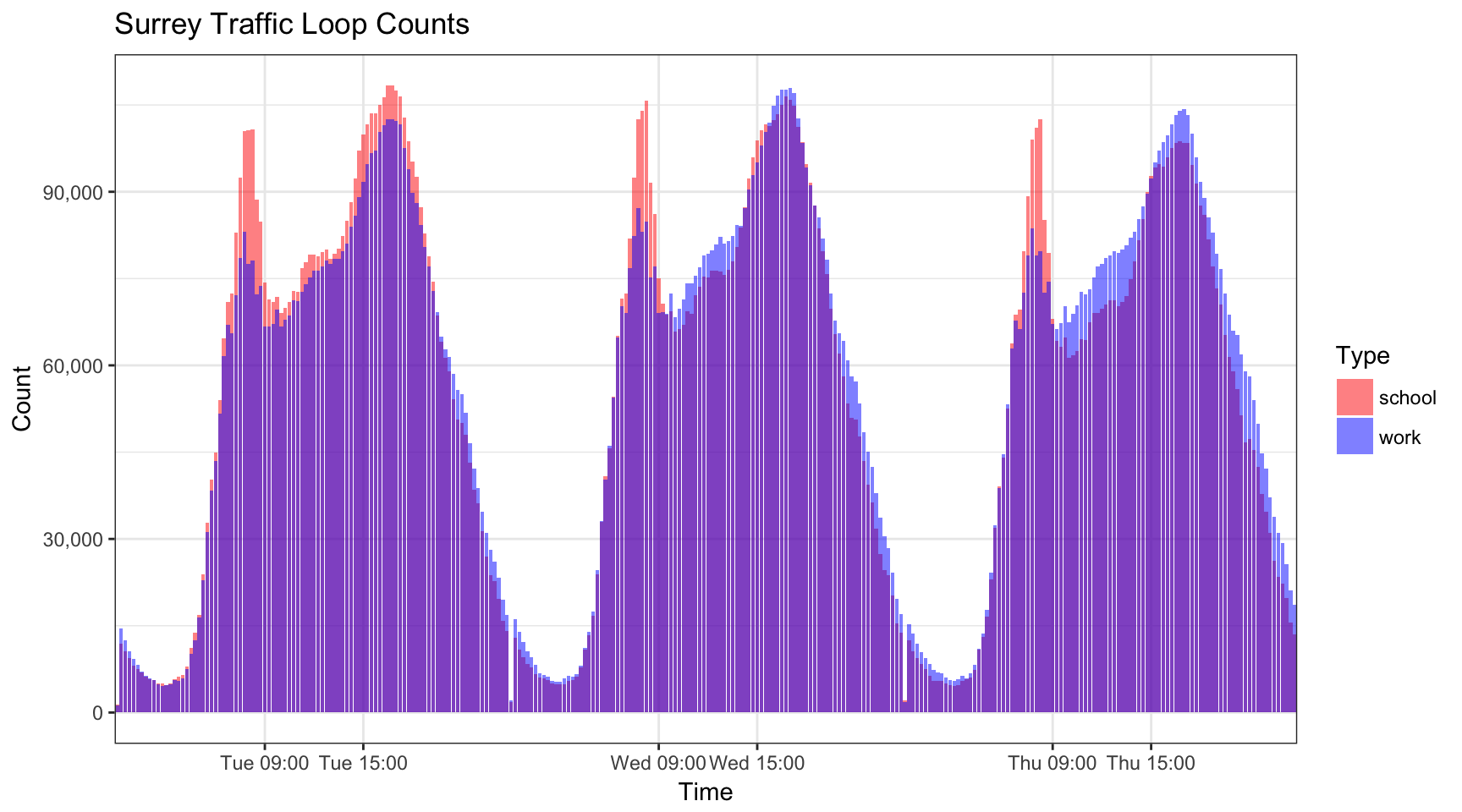

We compare traffic counts for a regular work day before and after school starts. To this end we use the start of the summer semester as a test, mostly because we don’t have enough data for the beginning of the spring term and because we don’t have good comparables for non-school days over the winter break.

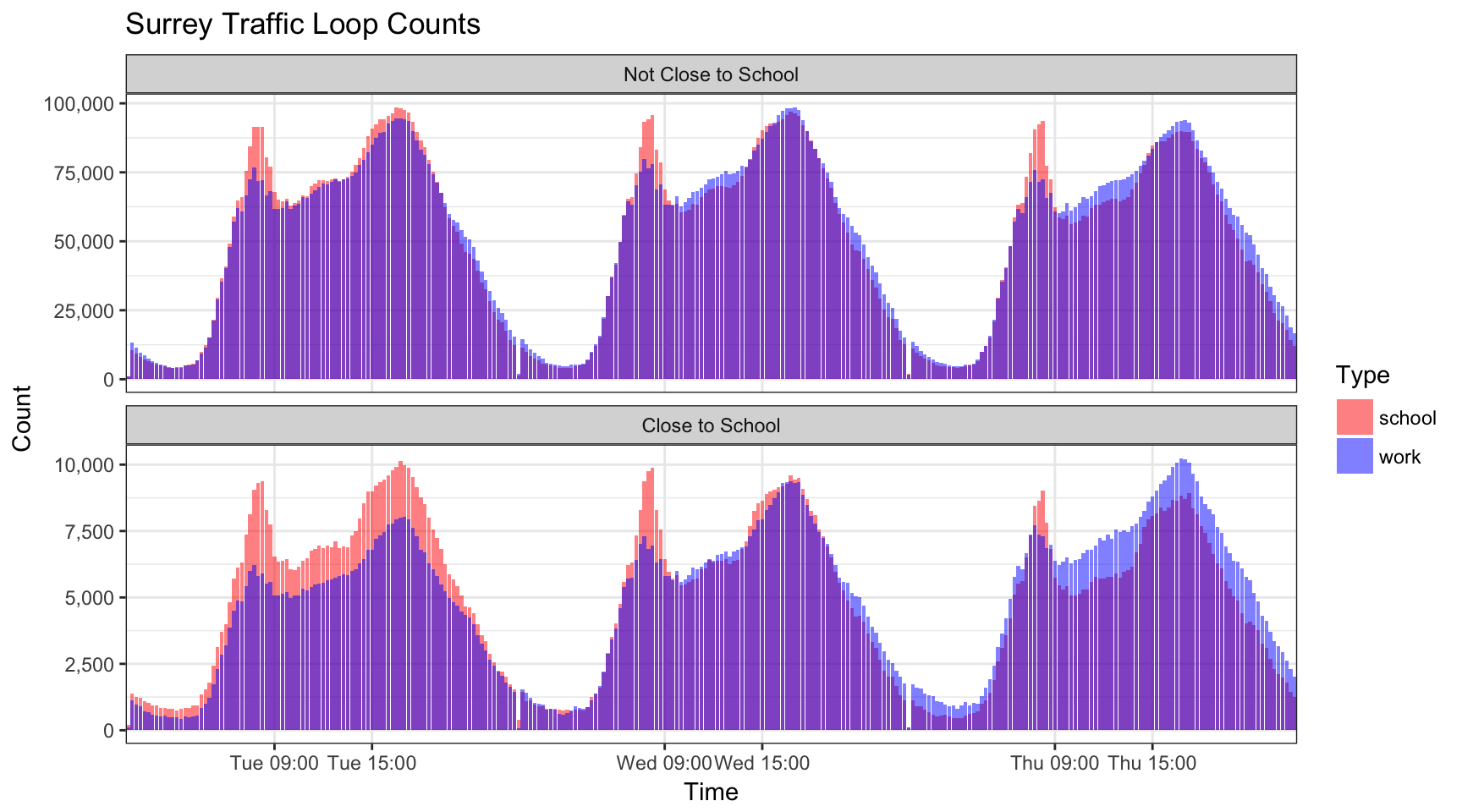

One issue is that the data is surprisingly volatile. To overcome this we average over Tue, Wed, Thu for three weeks prior to school start this summer compared to three weeks after school start. This should give us a first approximation of how traffic changes between school and non-school days, with the understanding that some of the difference may be due to more people being on vacation during non-school days and that there is a fair amount of children being driven to camps instead of schools during non-school days.

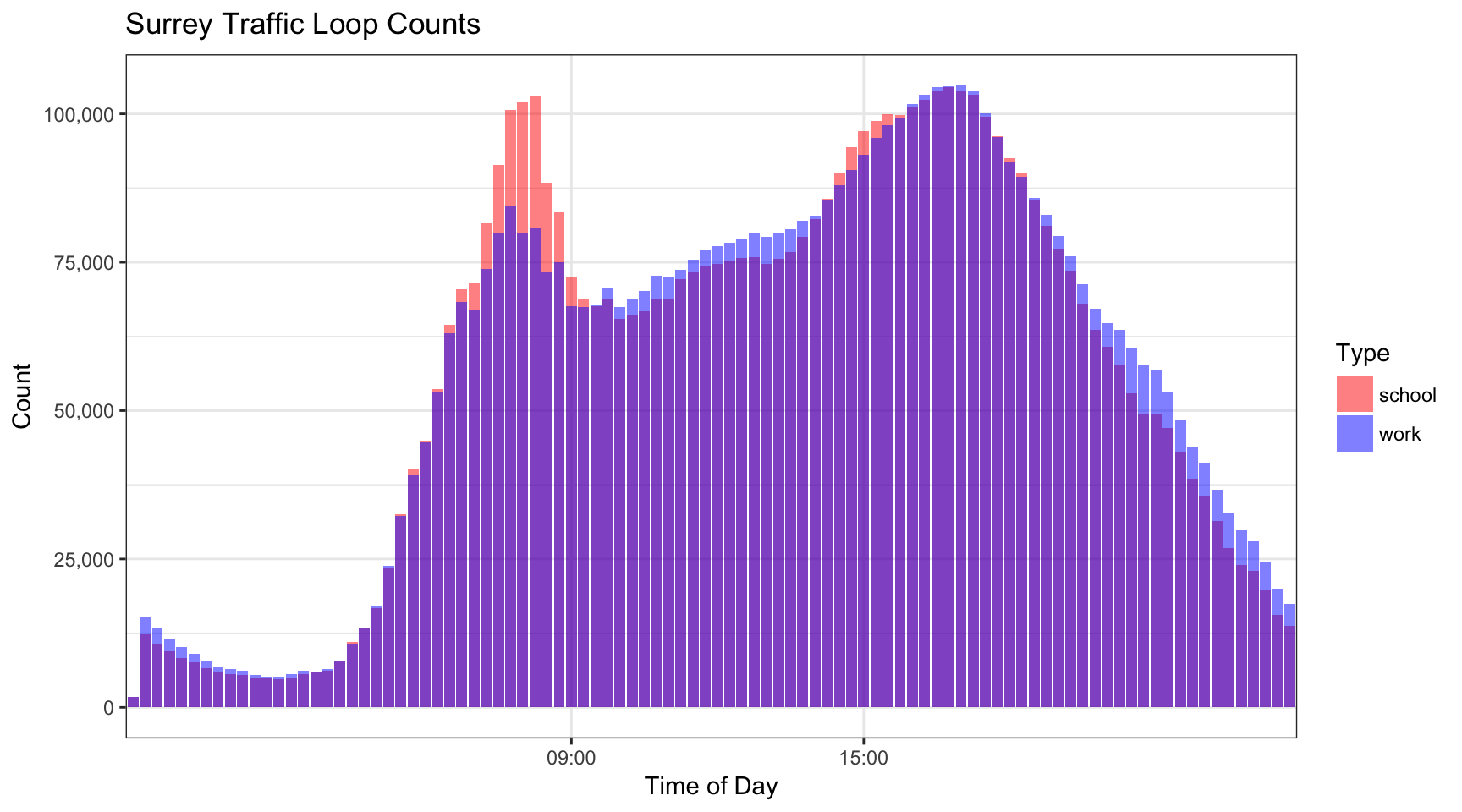

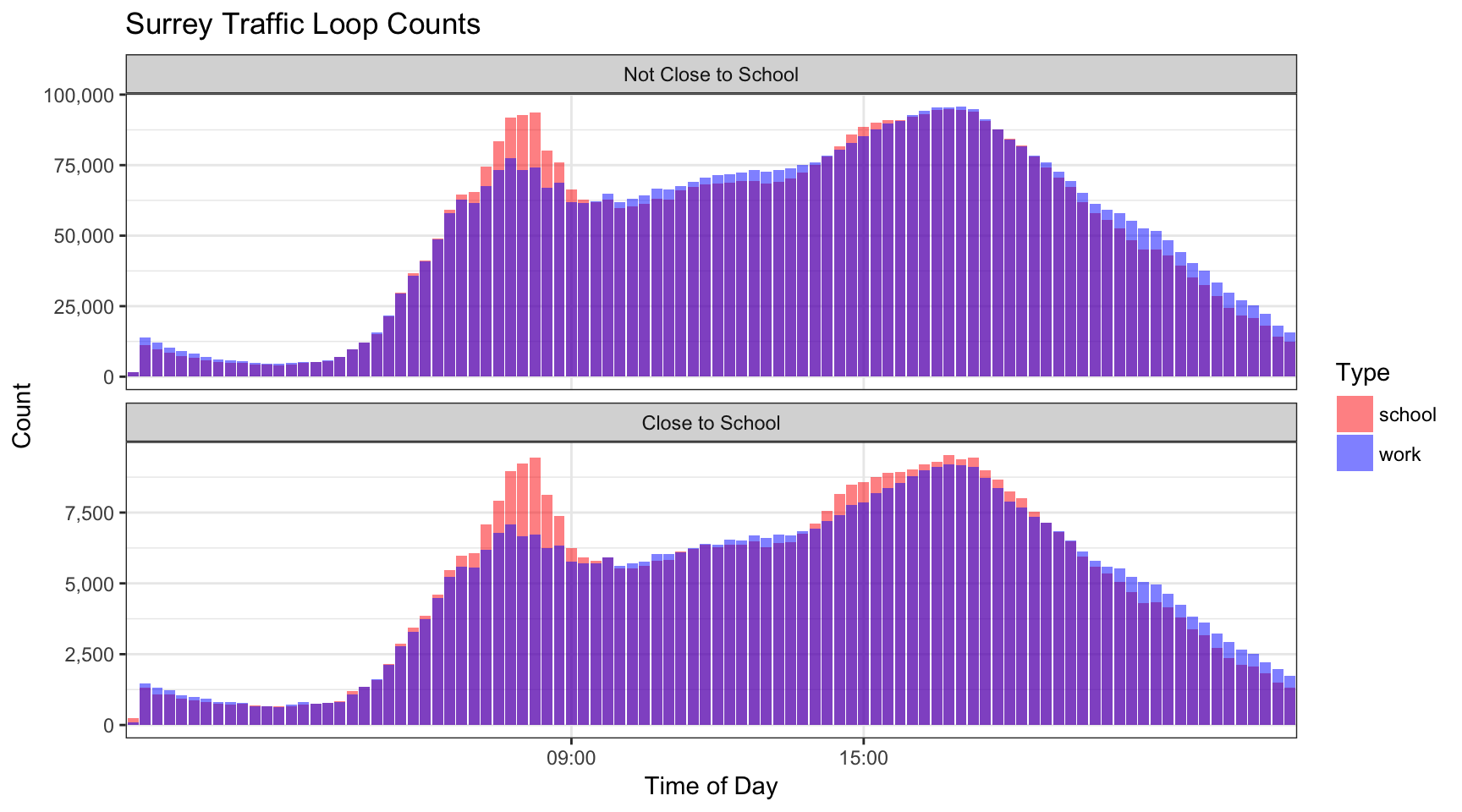

The data still shows substantial volatility even after averaging over three weeks, but there appears to be a consistent uptick in traffic associated with pickup times on school days, as well as increased traffic volumes within an hour before dropoff time. We can further average over the three weekdays to get a cleaner picture.

Without diving deeper into the changes in traffic patterns that are not associated with the start of the school year it is hard to make definite claims. The spike at pickup time around 3pm seems to correlate very well with the hypothesis of increased school traffic, but that argument seems a little harder for the morning spike that occurs quite a bit earlier than the 9am dropoff time slightly earlier than the Surrey schools dropoff time that varies between 8:30 and 9:00 am as Chad Skelton pointed out, who also notes classes are out already at 2:30pm at some schools.

We will have to dig a little deeper to tie this to school traffic.

Schools

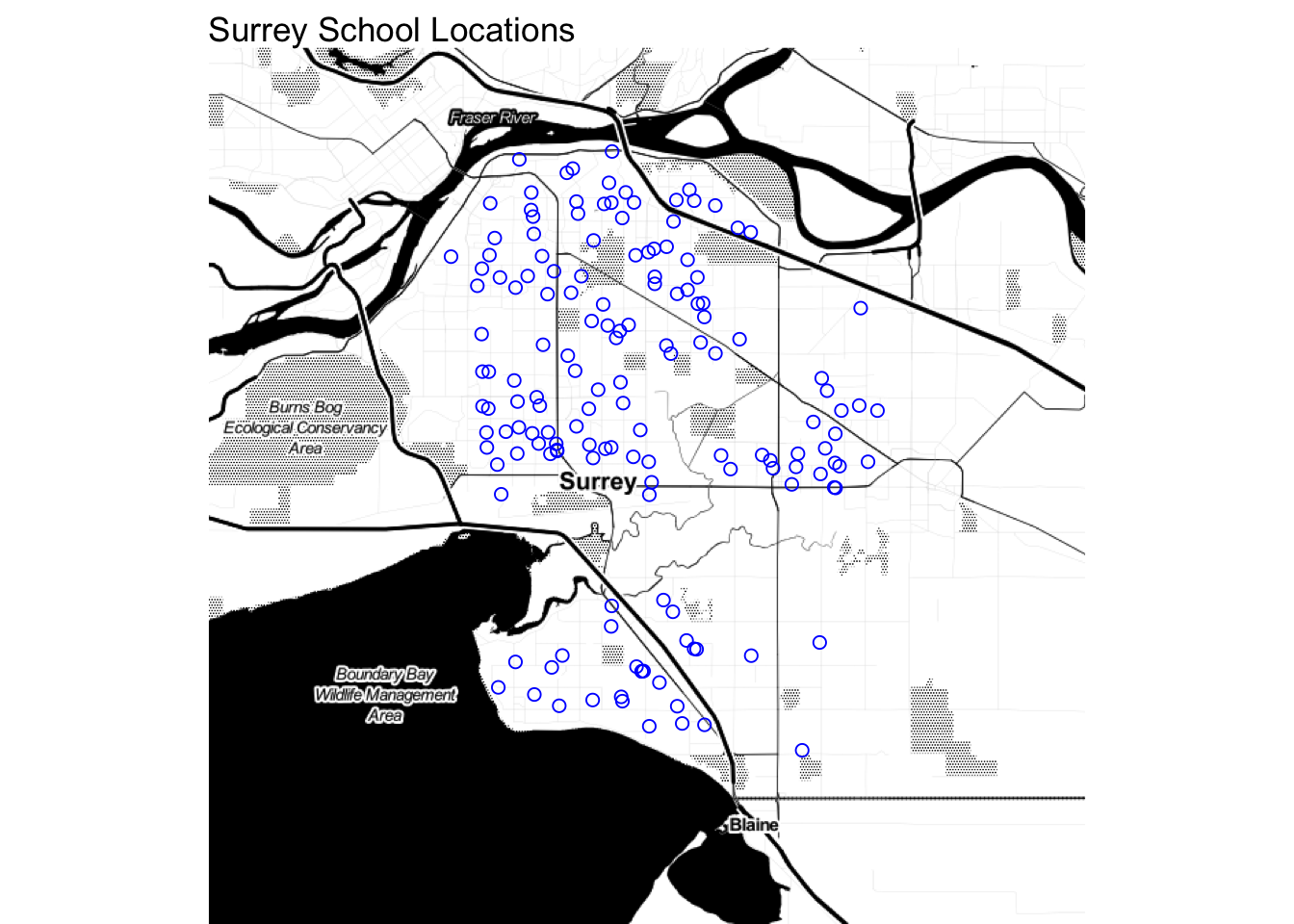

If change in traffic has anything to do with schools it stands to reason that on balance the change will be more pronounced in proximity to schools. So let’s load in the school data.

With this we can divide traffic loops into two groups, one within 200m of a school and the other more than 200m away from schools. We could choose a softer cutoff strategy or run a more broad analysis using school proximity, and we probably also should account for school enrolment, but that gets complex fast and won’t fit into my evening blog post time budget.

Armed with this data we can run our analysis separately for the two types of traffic loops.

What we see here is that while the effect seems more pronounced close to school on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, the reverse appears to be true on Thursdays.

Aggregating over all three workdays we see however that the spikes during school days do correlate with proximity to the school. So we do feel that this preliminary analysis verifies with some confidence that there is indeed a measurable uptick in traffic that can be associated to school dropoff traffic. Again, it is hard to quantify this in light of the noise in the data and that our control period likely also contains dropoff and pickup traffic to camps, some of which are also located at schools.

Summary

It appears that an increase in school-related traffic can be seen in traffic loop data, and it would be worthwhile to refine the methods and explore this more thoroughly. As always, the code to reproduce this analysis is available on GitHub for anyone interested in reproducing or refining the methods.

An obvious way to extend this is to compare instructional to non-instructional days, as well as to refine the association of traffic loops with schools and also account for school enrolment.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{school-traffic.2018,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {School {Traffic}},

date = {2018-01-09},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2018-01-09-school-traffic/},

langid = {en}

}