In the past weeks I got interested in several news stories on aboriginal youth admissions to correctional services, adult incarceration rates and frequency of getting carded. I have this habit that when something interests me I go grab the original data and take a look myself. Having done this three times on related issues within a fairly short timeframe I decided to throw my code snippets together into a blog post.

TL;DR

The takeaway is that no matter how you look at things, aboriginal people are overrepresented in our correctional systems, as well as when it comes to just getting carded on the street. This clearly shows that the long shadow of Canada’s ugly history towards aboriginal people is still very present in today’s experience of aboriginal people. It points to sytemic failures within the Canadian system lasting to this day, much work is still to be done along the path to reconciliation.

Youth admissions to correctional services

This is the first article I read, and in many ways the most troubling. If we can’t reduce youth admissions to correctional services, it will be even harder to reduce adult incarceration rates. Indeed, another report on this topic notes that

Sinclair recalls that in a survey conducted in 1991, more than 70 per cent of adult inmates in the federal system had prior experience with the child welfare system.

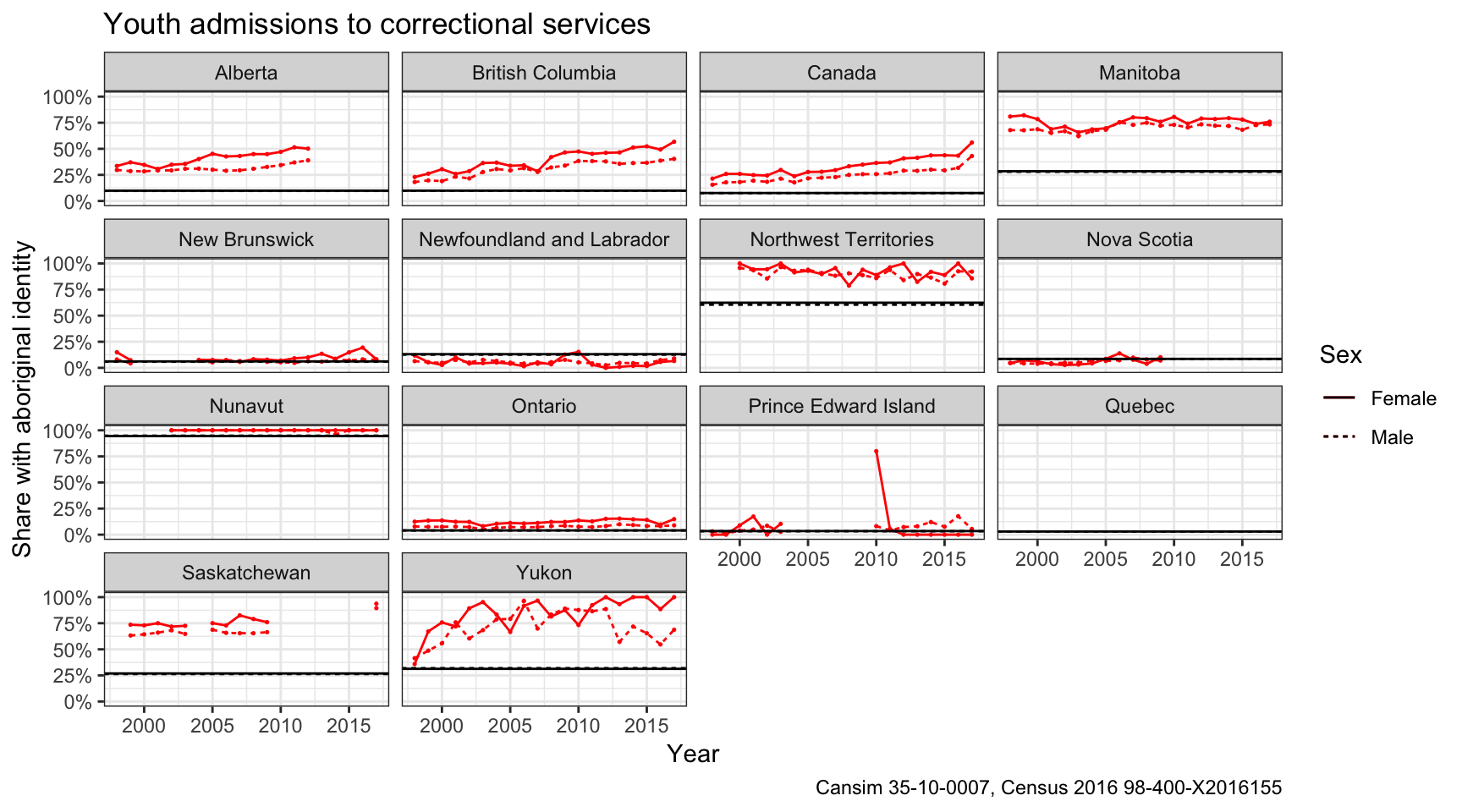

Here we added the share of the youth (under 20) population with aboriginal identity in 2016 as horizontal black lines. We see that the the frequency of admissions of youth with aboriginal identity is consistently above the aboriginal share in the general population in some provinces.

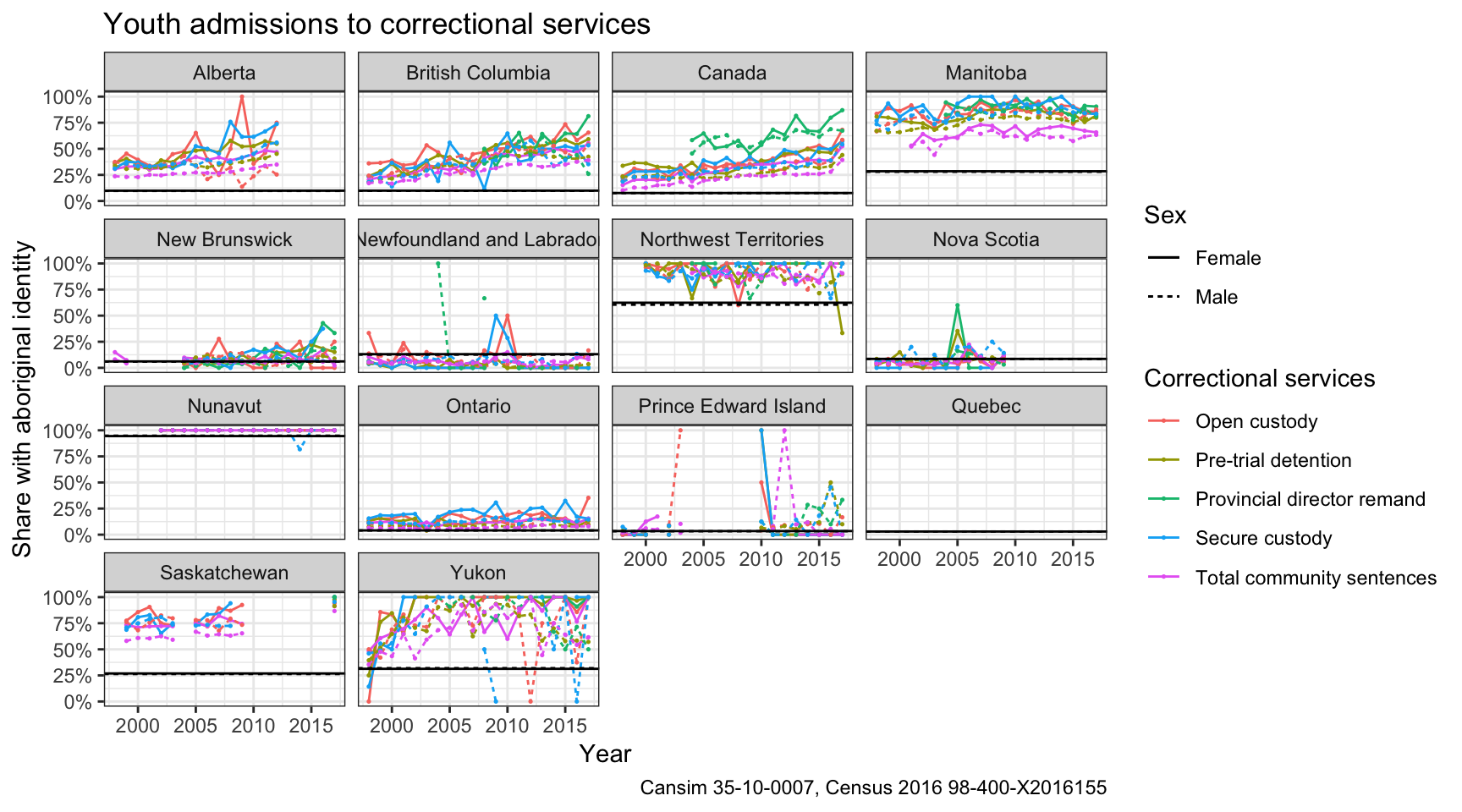

We can split the data into groups of correctional services.

This shows a discrepancy in the type of correctional services for aboriginal youths.

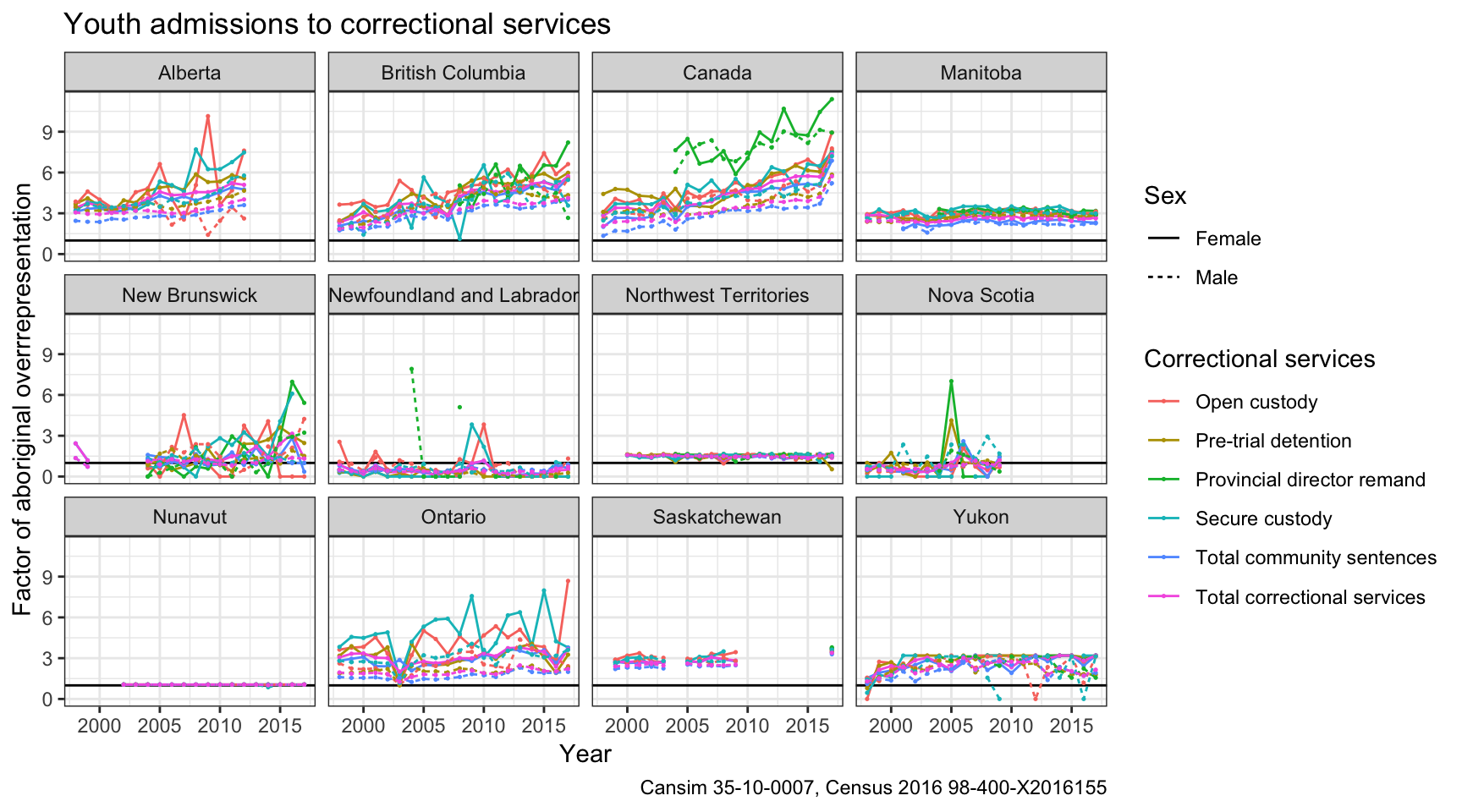

We can normalize the data by dividing by the share of aboriginal youth in the overall youth population in each region in 2016 to show the “factor of overrepresentation”. The share of aboriginal youth in the population may have changed over time, this analysis could be refined by folding in older census data.

This shows alarmingly high rates for British Columbia, as well as Alberta, although Alberta is missing data for recent years. The overall Canadian numbers are skewed when looking at sub-types like Provincial director remand that are dominated by a few provinces with higher aboriginal share.

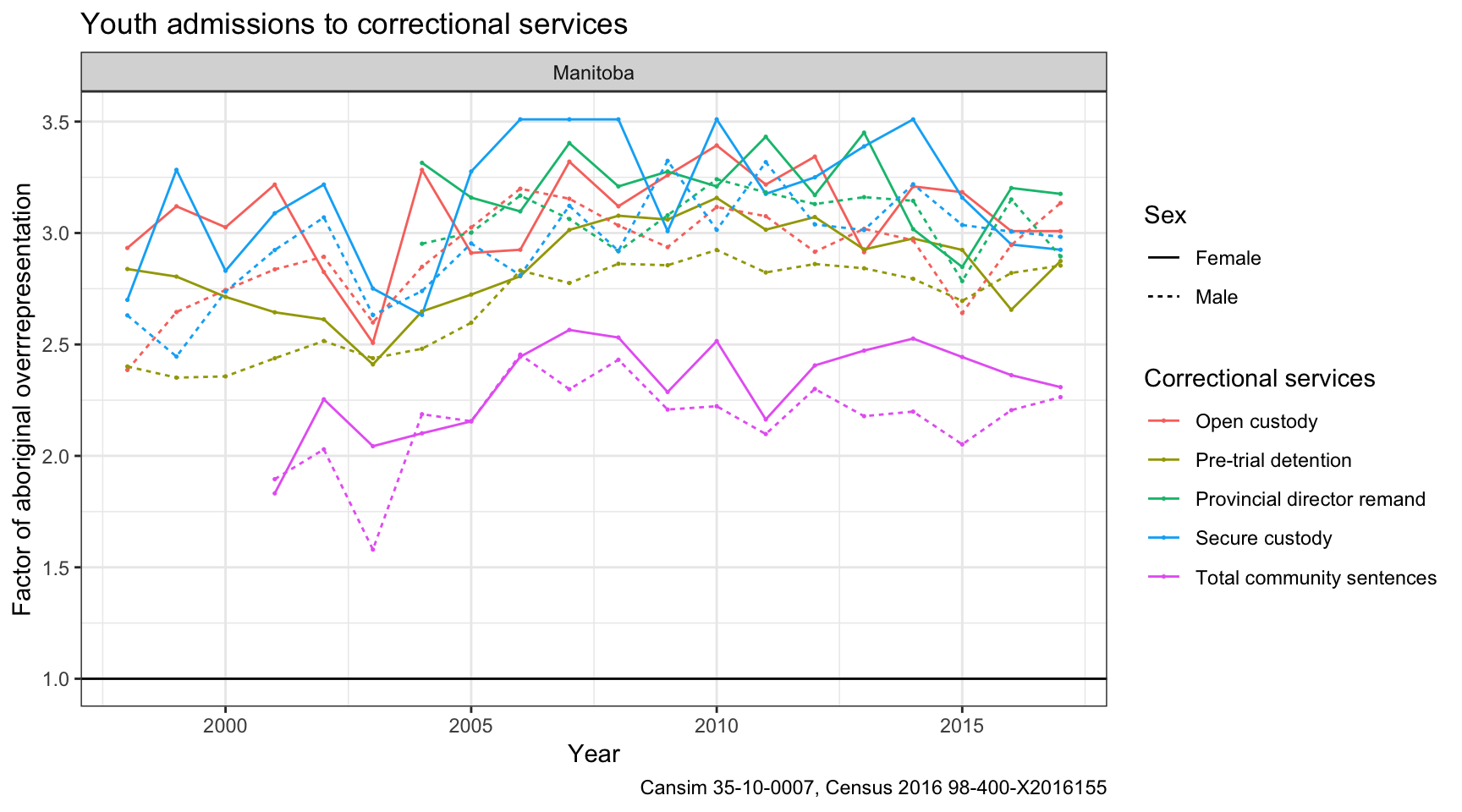

Looking at Manitoba in particular

we notice that the factor of overrepresentation is highest for secure custody and lowest for community sentences, which should receive more scrutiny.

Adult custodial admissions

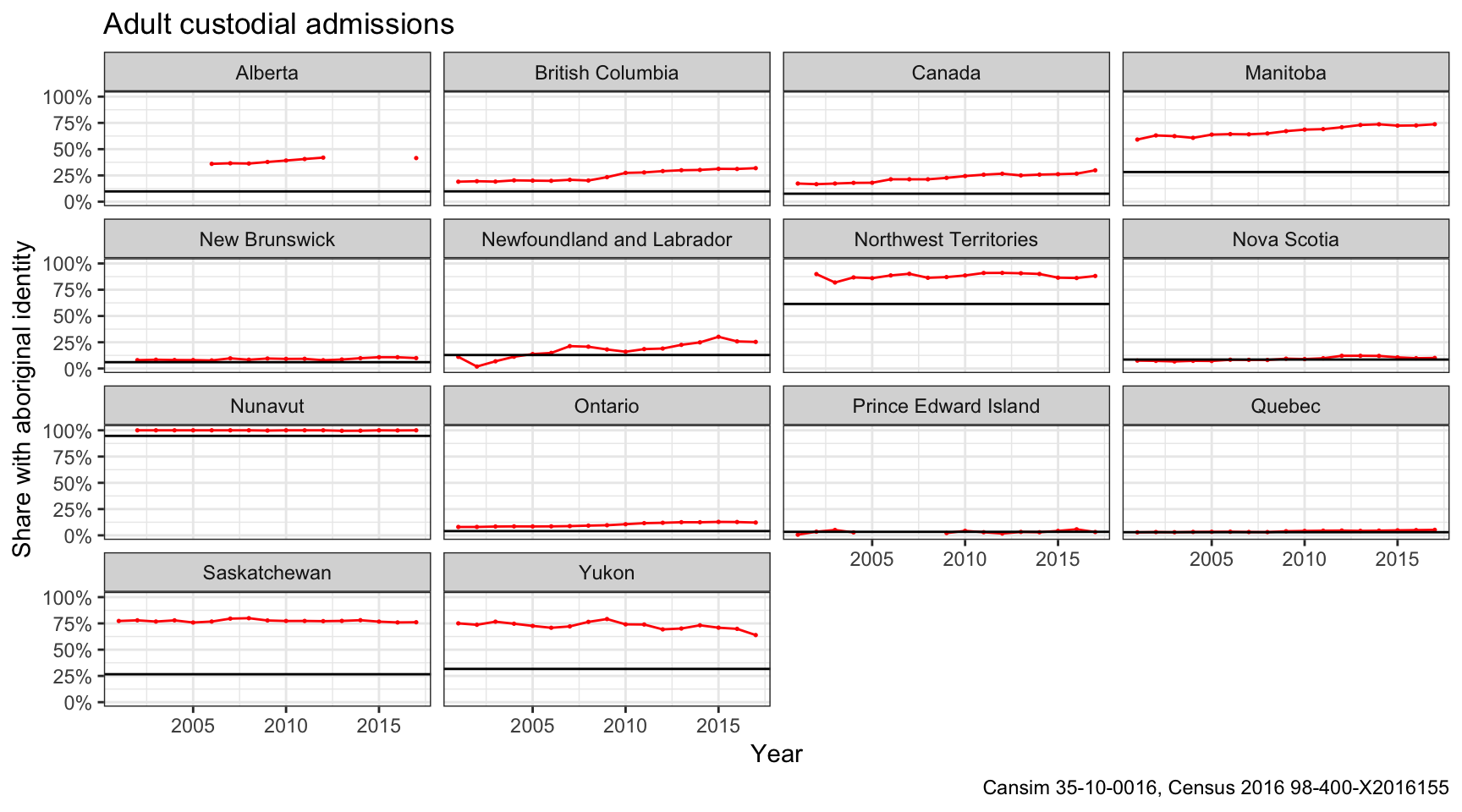

Just like before we can look at the share of admissions to custodial services that have aboriginal identity, which has been climbing Canada-wide as reported by Angela Sterritt.

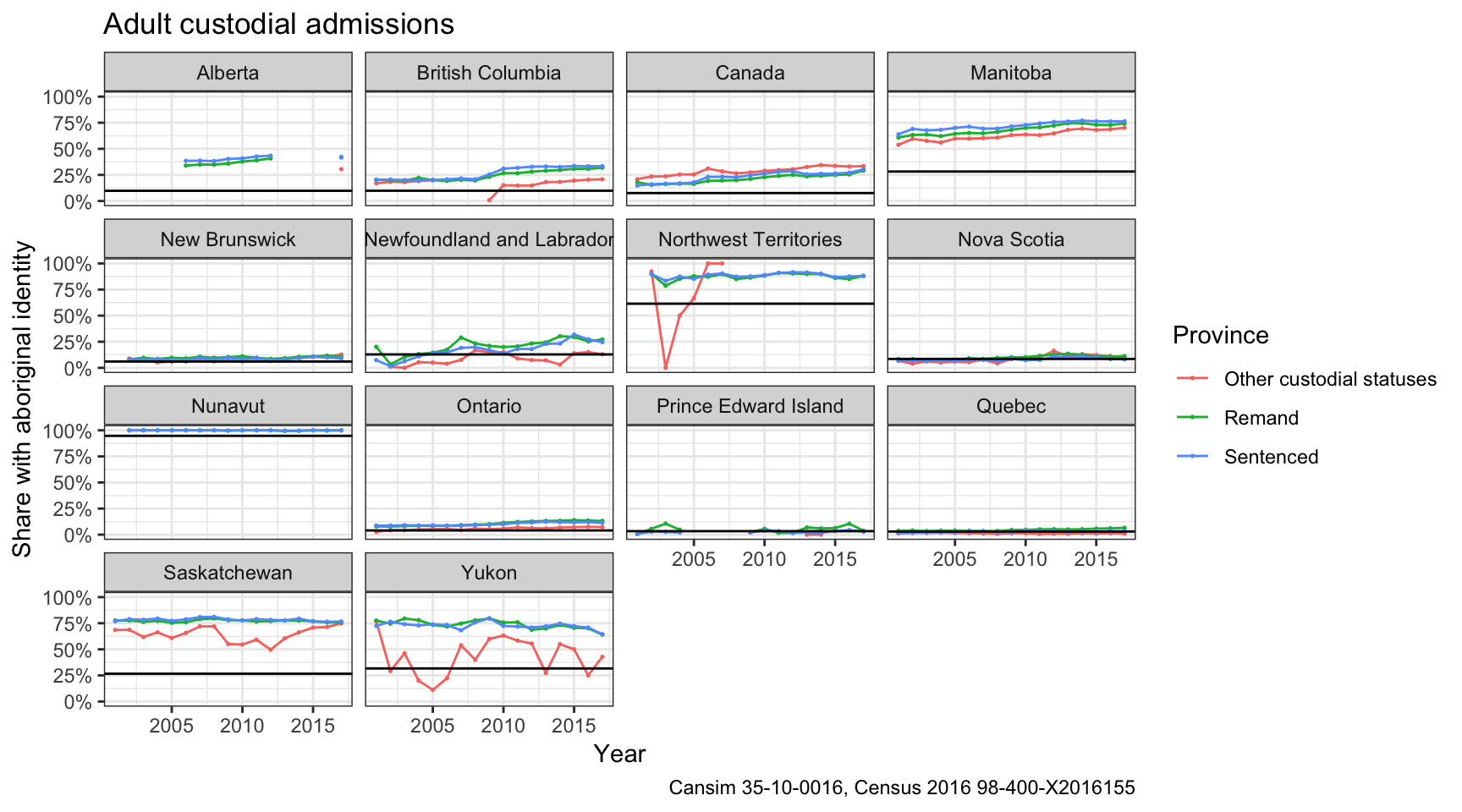

Splitting this out by type of admission

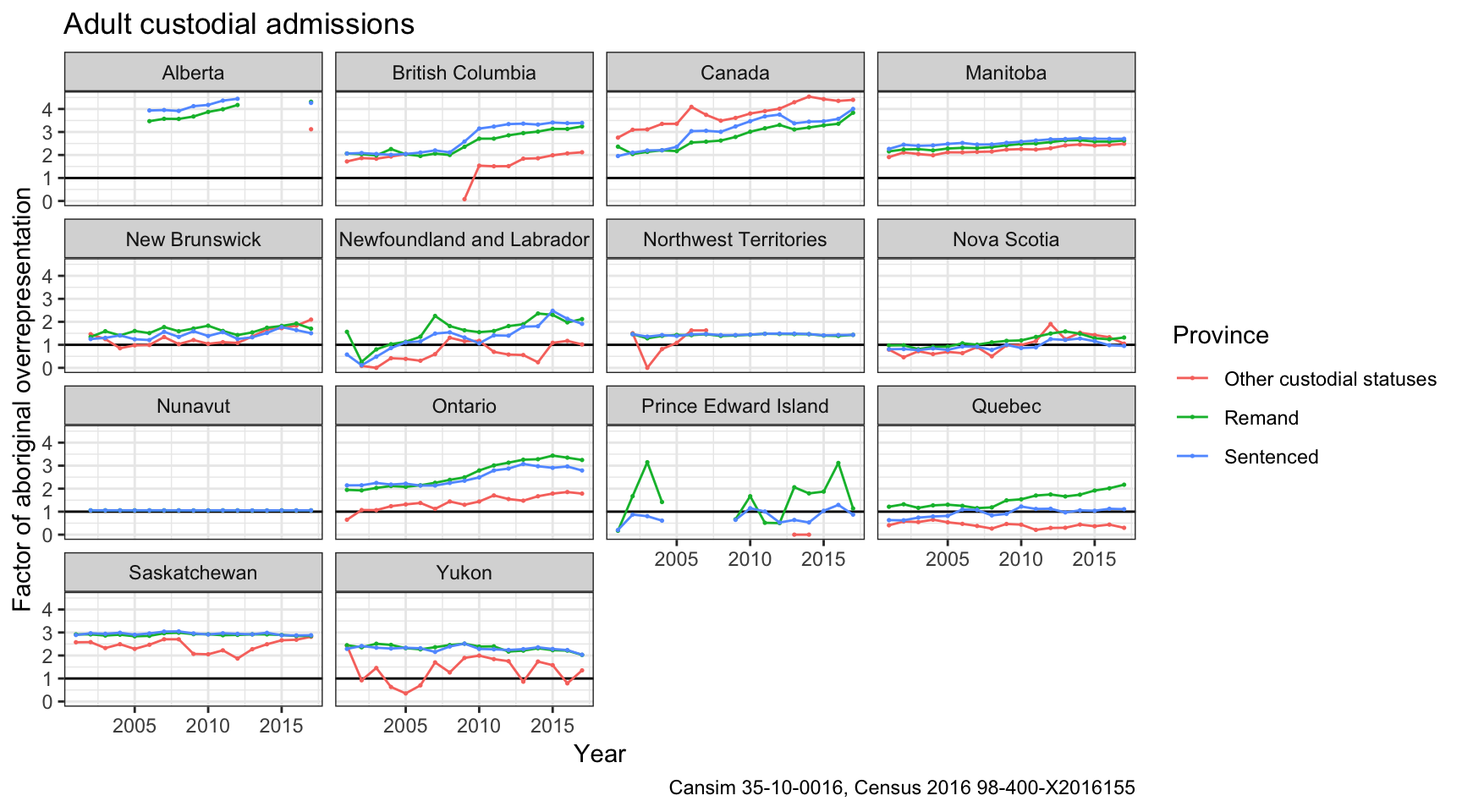

we again notice disparate shares in some provinces. We can again normalize the data by the share of aboriginals in the adult (20+) population to examine the factor of aboriginal overrepresentation.

Here we see that Alberta and British Columbia are again the provinces with the highest aboriginal overrepresentation, and we also notice that the the overrepresentation has been getting worse over time in some provinces.

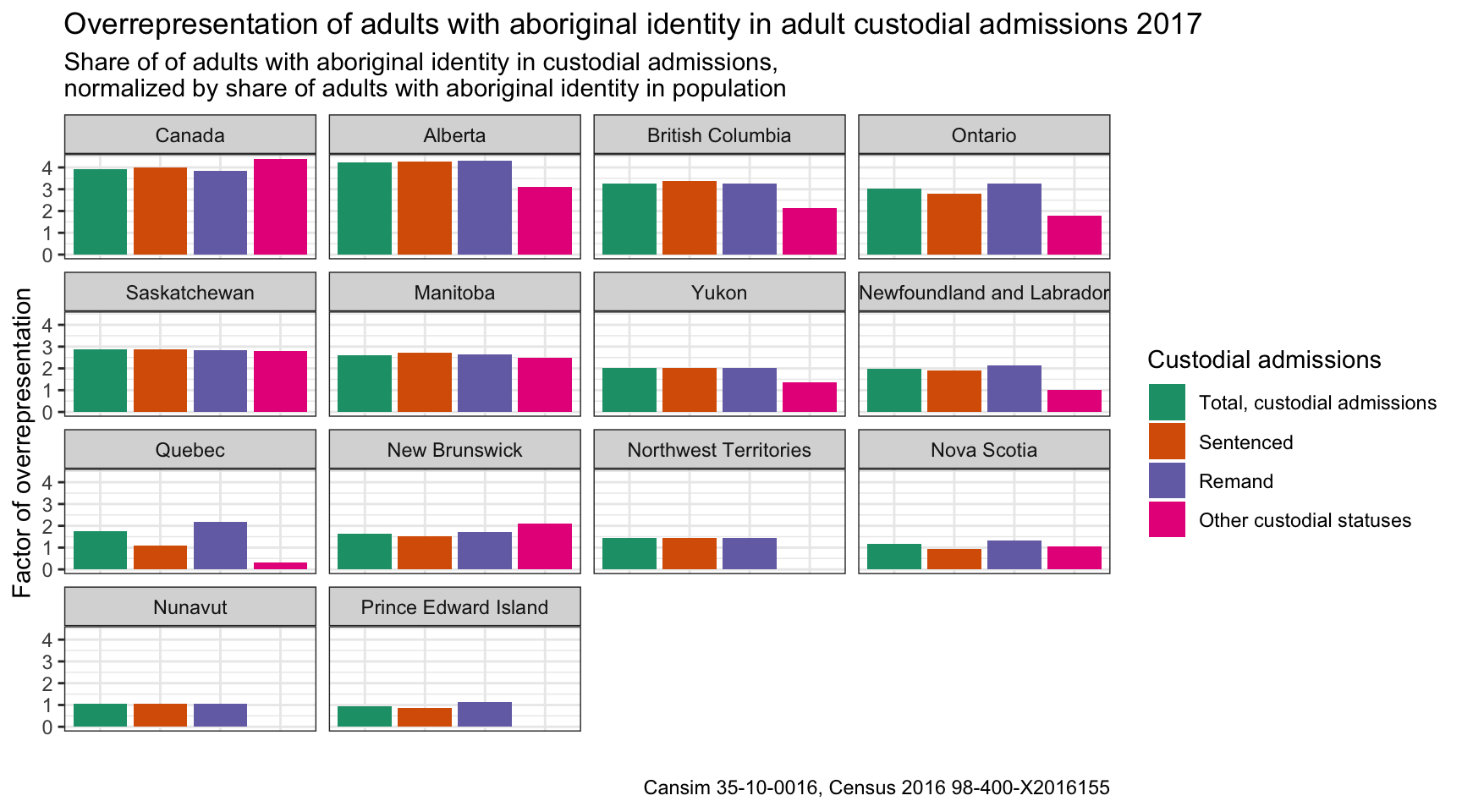

These graphs contain a lot of information and can be messy and difficult to read. To clean things up a bit we can focus on the last available year only.

Vancouver Street Checks

Lastly we turn to Vancouver street checks. It was reported yesterday that “1 in 5 women ‘carded’ by Vancouver police in 2016 were Indigenous”. The Union of BC Indian Chiefs and (UBCIC) and the BC Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) have filed a complaint with the Office of the Police Complaints Commissioner (OPCC) over data suggesting Indigenous people were being disproportionately street-checked.

This complaint is based upon data released via an FOI and posted on the Vancouver website. It’s in PDF format, so it requires a bit of scraping and massaging to get it into processeable form.

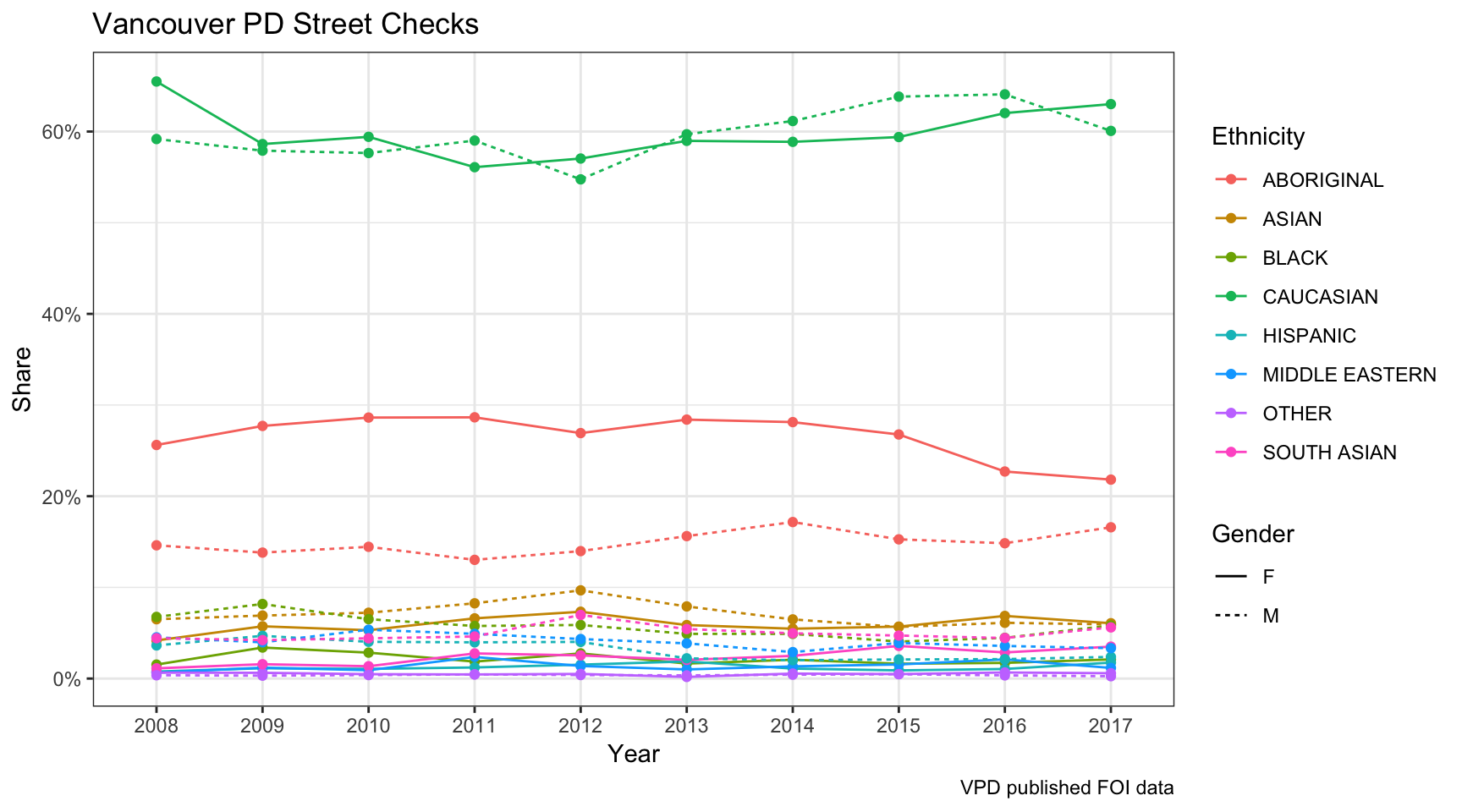

The data contains a breakdown of street checks by Ethnicity and Gender and we see how female aboriginals are disproportionally represented in the data.

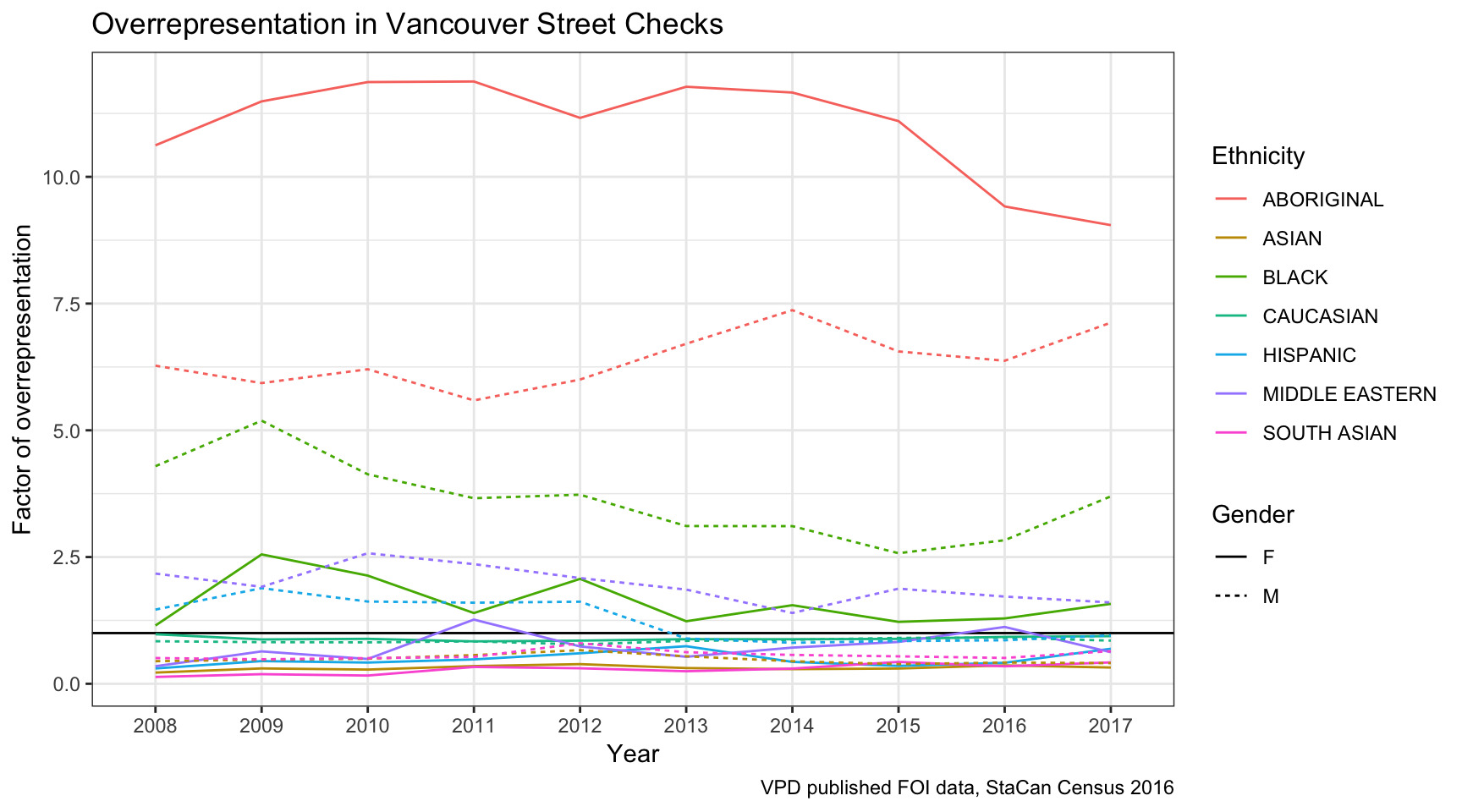

We can use data from the 2016 census for the City of Vancouver, as well as Musqueam 2 which is also part of the VPD jurisdiction, to compute the factor of overrepresentation like we did before.

This shows that aboriginal women are overrepresented by a factor 10, although there was a slight drop in recent years. Male aboriginal overrepresentation has been consistently lower, but trending slightly upward. People will not be surprised that black males are the next-most overrepresented group.

Next steps

These numbers are disturbing, and this analysis is just scratching the surface. It deserves more detailed look province by province. The disparate rates for different custodial services should also be examined more closely, and in this post we have not explored the full breakdown of custodial services that is available in the data.

As always, the code for the analysis is available on GitHub, the code automatically pulls in all the data needed and reproduces the analysis. This should make it fairly straightforward for anyone to copy, adapt and refine the results.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{aboriginal-overrepresentation-in-correctional-services-and-police-checks.2018,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Aboriginal Overrepresentation in Correctional Services and

Police Checks},

date = {2018-07-13},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2018-07-13-aboriginal-overrepresentation-in-correctional-services-and-police-checks/},

langid = {en}

}