Disclaimer

Apologies up front, this is a bit of a hodge podge of a blog post. I have about half a dozen stubs on rental data and affordability that I looked at at some point while trying to understand some aspect of rental affordability. But it’s a large and complex topic, and I never took the time to distill out coherent storylines. Rather than keep pushing things off I decided to grab a couple of relevant pieces and put them together in a short blog post. Some of this is based on public census release data, other parts are based on a a custom tabulation that I have also used in a previous post and that I am unfortunately not at liberty to share the raw data.

There is no clear storyline in the data, rather its a bunch of different aspects that partially intersect and that illuminate some aspects of rental affordability in the City of Vancouver. Hopefully someone will find some of this useful

What is affordability?

In Vancouver we talk a lot about affordability. Different people have different definitions of what affordability is. And affordability is not the only metric that counts. StatCan says a household is in core housing need if the household does not meet at least one of the adequacy, affordability or suitability standards. A dwelling unit is adequate if it does not need major repairs, affordable if the household spends no more than 30% of total income on shelter costs, and suitable if it is not overcrowded (meets NOS standards). The universe excludes non-family households with at least one maintainer between the ages of 15 to 29 attending school full-time, as well as households with shelter-cost-to-income ratios at 100% or above. Additionally CMHC ran estimates for rents by number of bedrooms (in good repair) in each community, and it does not consider a household in core housing need if such rents would be affordable to a household that currently does not meet the core housing criteria.

Affordability is part of core housing needs, but there are households in core housing need whose housing is affordable and households that don’t meet the affordability cutoff that are not considered in core housing needs.

Often we see the affordability metric being used without the nuances that the core housing metrics introduce, and StatCan reports the proportion of households with income greater than zero spending more than 30% of income on shelter in their regular census releases, as well as the proportion of households spending 100% or more of income on shelter.

The latter category is difficult to interpret. Sometimes people exclude these when reporting household affordability statistics just like the core housing need definition does, as these are generally dominated by student households and households that otherwise don’t fall into the usual framework of people struggling for housing. In Vancouver, owner households in that category have been interpreted as a sign of undeclared income. Income volatility is at the root of another segment of such households.

At other times people include these households when reporting on affordability metrics. As mentioned above, CMHC excludes student households on top of that, which adds an additional filter to separate out households that CMHC considers in ‘transitional’ stages. Another worthwhile approach would be to take the cost of student housing into consideration and model affordability changes of students separately.

Custom tabulations can separate out renter and owner households, renter households in subsidized housing and market rental, households spending 50% or more of their income on shelter or less than 15% of income on shelter. For specific questions, one can tailor custom tabulations to report different cutoffs and slice by other variables of interest.

Affordability standards and City of Vancouver affordability

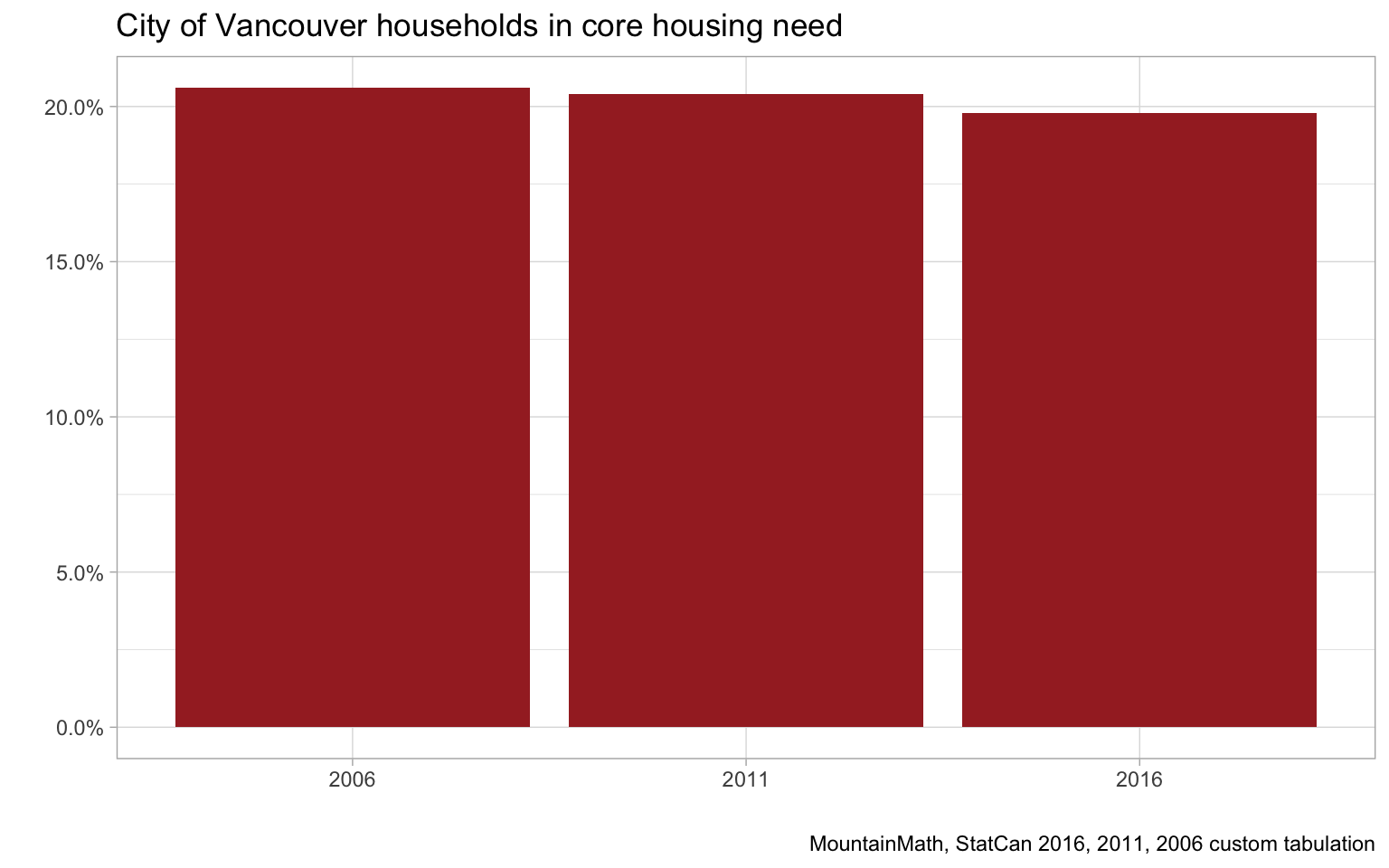

Census data shows that using shelter-cost-to-income ratios, City of Vancouver affordability has slightly improved from the 2006 and 2011 censuses to the the 2016 census. This is of course in stark contrast to some other affordability metrics like median multiples that compare median home values to median incomes. So what’s going on? These metrics measure different things. Shelter-cost-to-income ratios, taken at the individual level, focus on how individual households are handling their housing costs. Ecological level median multiples look take median incomes in an area and compare these to median home prices. There are a number of underlying assumption behind median multiples to ensure this is a useful metric, for example that either everyone does or should buy a home, or that dwelling values are reflected in people’s rent, and that the composition of households in terms of seniors, students and working people is uniform.

These two metrics, shelter-cost-to-income ratio and median multiples, tell diverging stories of affordability in Vancouver. While researchers have been struggling with this since October 2017, it is curious that the media has so far been able to largely ignore this. News searches reveal that there are stories about the change in the shelter-cost-to-income ratio in Toronto, but nothing in Vancouver. It is probably no coincidence that affordability according to this metric worsened in Toronto, but improved in Vancouver.

So how can we interpret the improving of the shelter-cost-to-income metrics in Vancouver? We already separated out renters and owners, as renter households are far more likely to be stressed for shelter cost than owner households. And the metric still improved for owners and renters when separated out.

Another view into this is using a custom tabulation put out by StatCan and CMHC to look specifically at core housing need.

Again, we see that the share of households in core housing need has slightly decreased in the City of Vancouver. This custom tabulation also allows us to better understand the nuances in the core housing definition, in particular how it is applied and what population is excluded from the universe.

Overall the share of households in the City of Vancouver considered in core housing need was 19.8% in 2016. This includes households not meeting one of the three core housing need standards, including the affordability standard. But this is significantly lower than the share of shelter-burdened households often pegged at 36.6%.

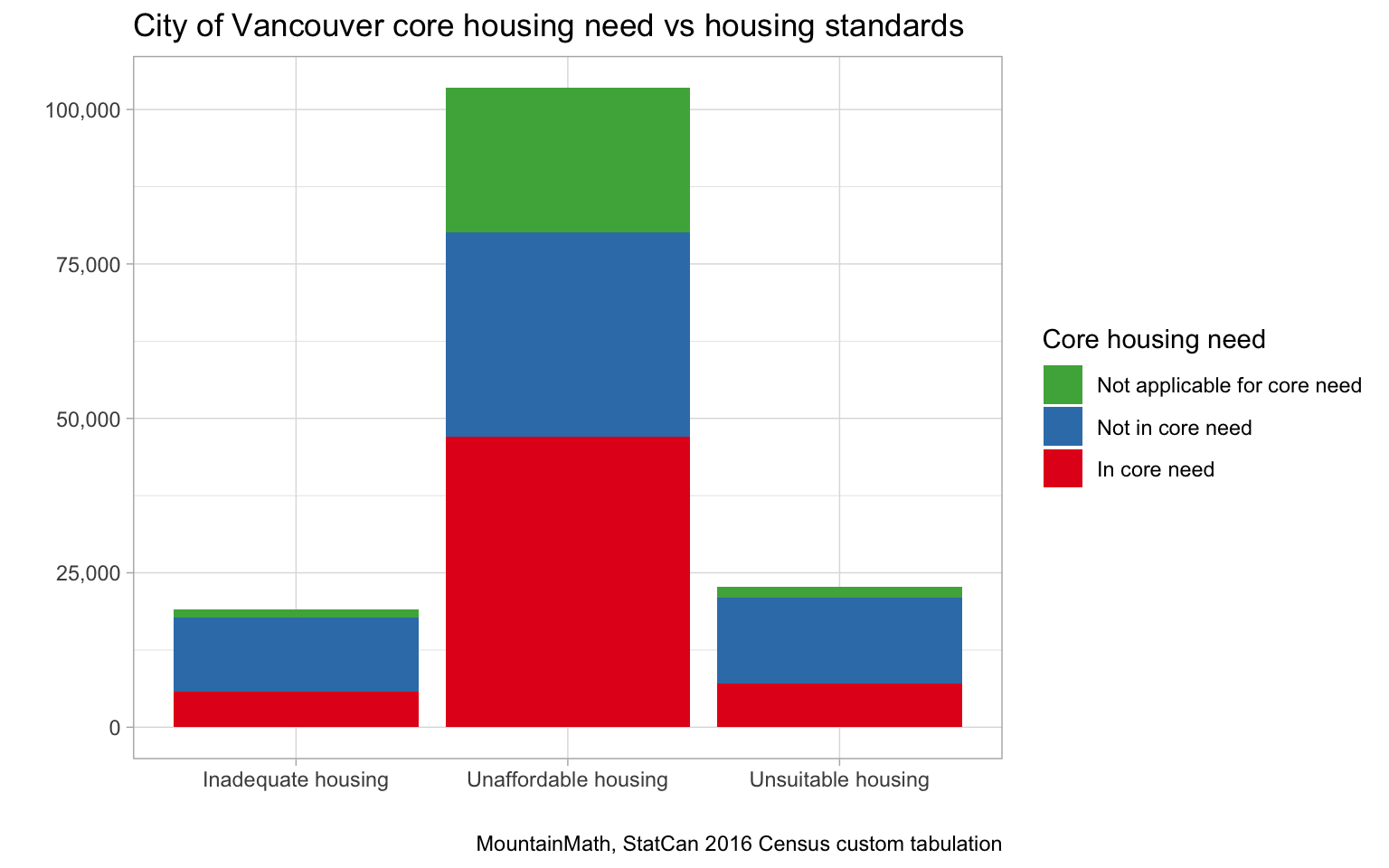

It is instructional to look at the difference between the straight-up 36.6% of households (with income greater than zero) and the portion of them that CMHC deems in core housing need.

The bottom bar in each of these stacks count the number of households in core housing need not meeting the specified metric. The top bar counts the number of households with (income greater than zero and) shelter cost higher than income that were excluded from the core housing universe, and that don’t meet the specified standards. The middle bar counts households not meeting the standard that could afford a suitable and adequate accommodation in the community, as well as the non-family full-time student households that don’t meet the specified standard but have higher household income than shelter cost.

This explains the differences we see in how these metrics are applied. We can slice the data further to better understand the households that are facing affordability challenges in Vancouver. From the high-level numbers we see that renters in particular are having a hard time making ends meet in Vancouver, so for the rest of this post we want to focus on the City of Vancouver and explore the affordability of rental households in more detail.

Regional context

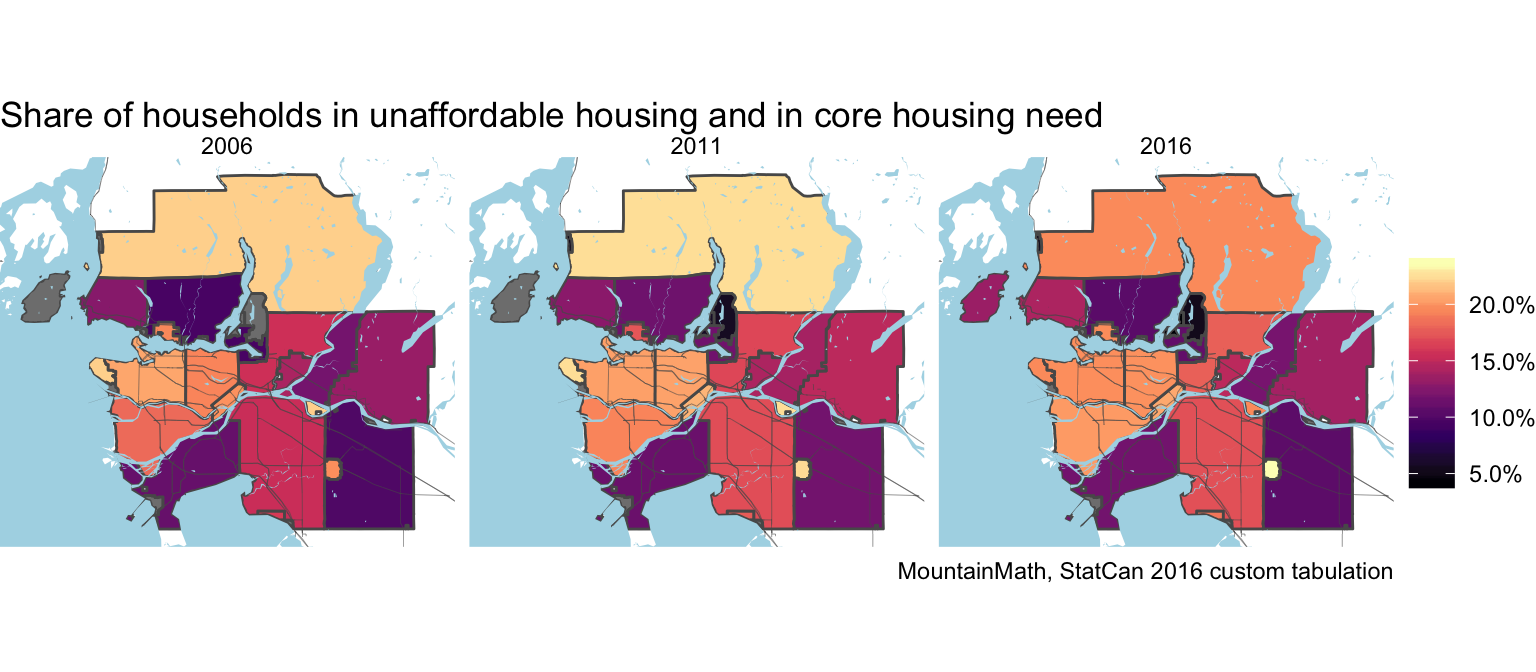

This highlights how households in unaffordable housing in core housing need are more prevalent in central regions, although the City of Langley is a curious outlier. Typically outlying regions make up for there more affordable housing options with higher transportation costs. We have explored the tradeoff between housing and transportation costs in the past (using 2011 data) at the ecological level, it would be worthwhile to revisit this with 2016 data, as well as computing this at the individual household level via a custom tabulation.

Shelter-cost-to-income ratios of renter households

Renters are at the core of affordability. Canadians value home ownership, but ownership is not a core housing need. As discussed above, CMHC explicitly excludes shelter-cost burdened homeowners that could afford to rent a suitable dwelling in the community from their core housing need data. But if someone can’t afford to rent in the community, they are getting displaced.

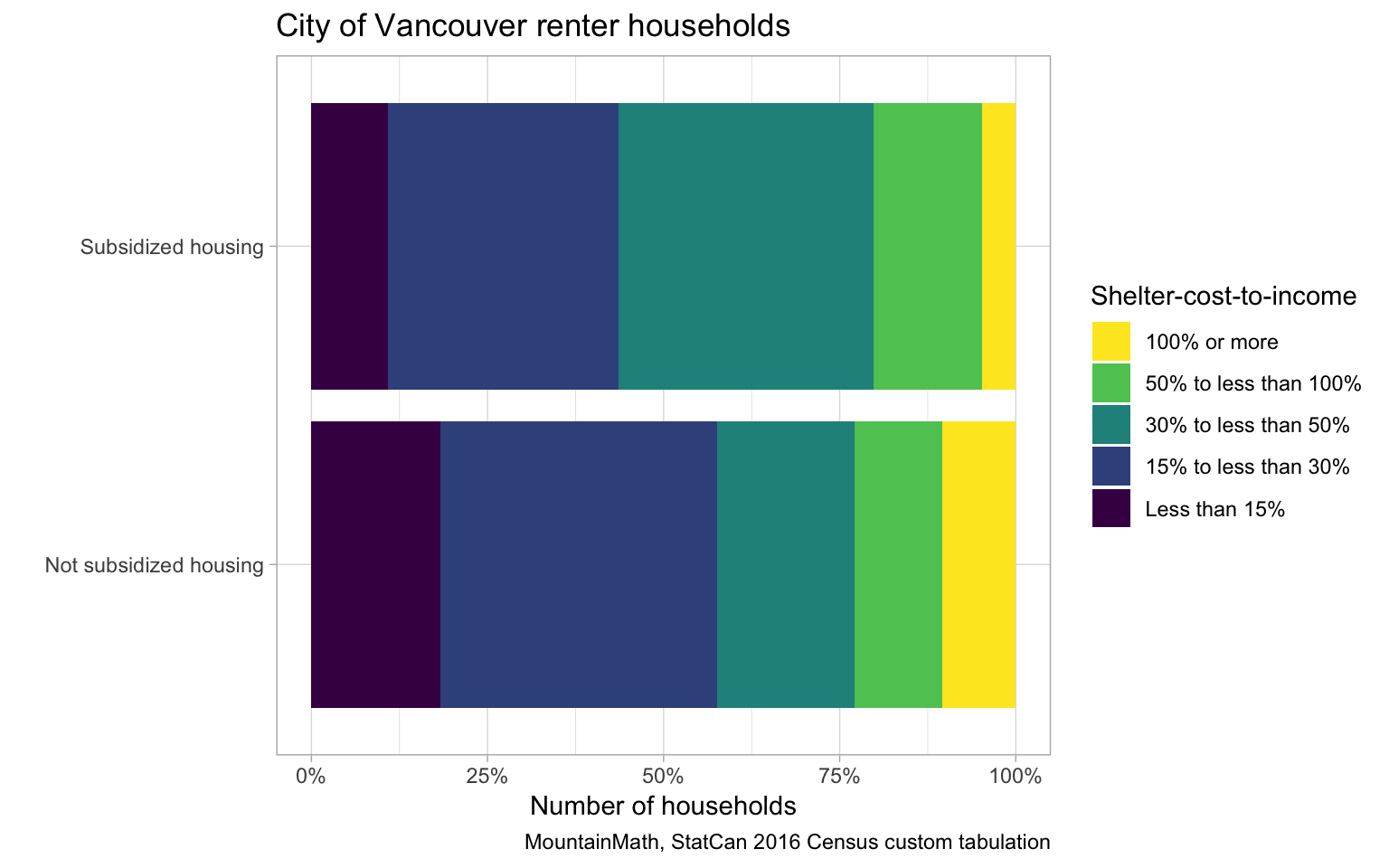

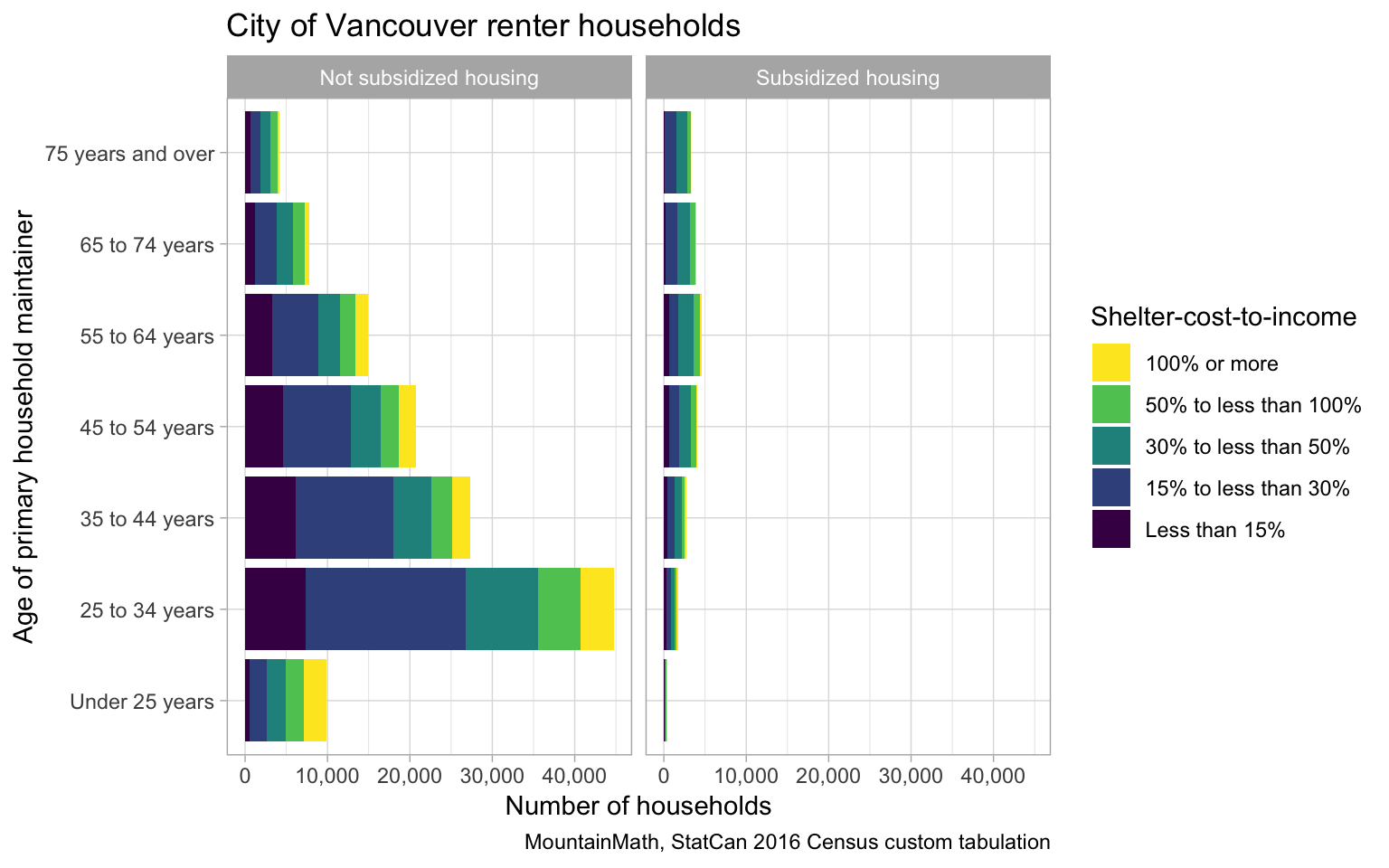

When looking at renter households, we like to distinguish those in subsidized housing from those in market housing. We expect different types of households and different types of rent between these groups, so it is useful to keep them separate. Overall, 13.8% of renter households are in subsidized housing in the City of Vancouver. That includes cases where the unit is subsidized, or where the household receives cash rent subsidies.

When looking at the overall affordability picture there are fewer comfortably housed renter households, those paying less than 15% or less than 30% of income on shelter costs, in subsidized housing than in market rentals, which is to be expected. Comfortably housed households tend to be more affluent and won’t qualify for subsidized housing. However at the high end, we see that there is a higher share of severely shelter-cost burdened households, those paying 50% to 100% of their income on housing, than in market housing. As to be expect, the portion of households spending 100% or more of their income on housing is larger in market housing. As we have seen above, these are hard to interpret and CMHC does not consider these in their core housing need categories.

To get a better idea of these households, we proceed to slice the data by different variables.

We see that renter households in the City of Vancouver are overwhelmingly young. Households below the age of 25 have a quite different affordability pattern, a good portion consists likely of student households. Senior renter households also show a declining share being comfortably housed. For now, we will focus on households between the ages of 25 and 64 to approximate the labour force.

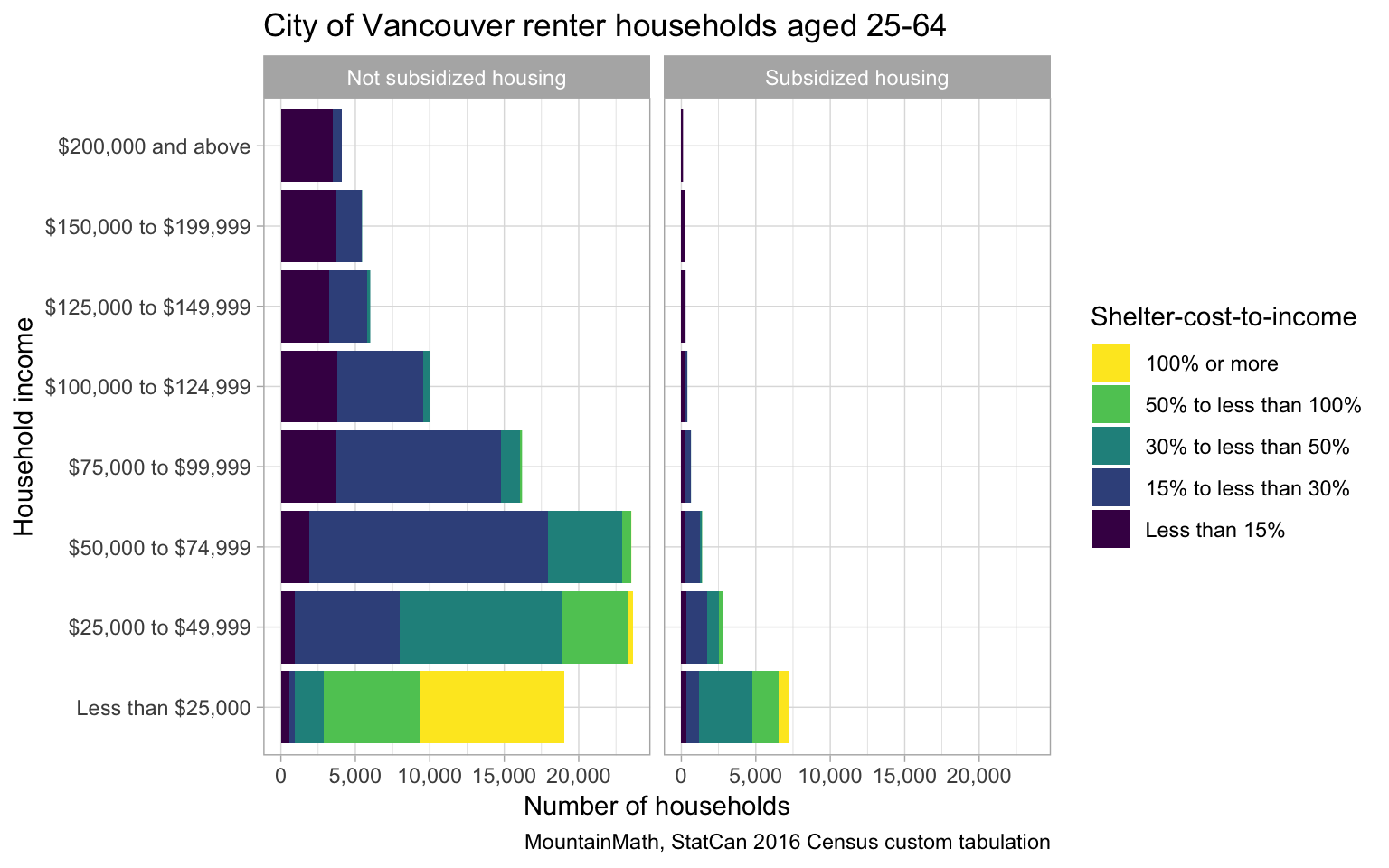

As can be expected, renters with income below $25,000 are severely strained, unless they are in subsidized housing. But even there the vast majority is shelter-cost burdened to severely shelter-cost burdened. It’s surprising to see 955 households with income above $100k in subsidized housing, as well as 21,380 households in market rentals spending less than 15% of income on housing, so being able to afford double their rent and utilities and still being comfortably housed spending less than 30% of income on shelter.

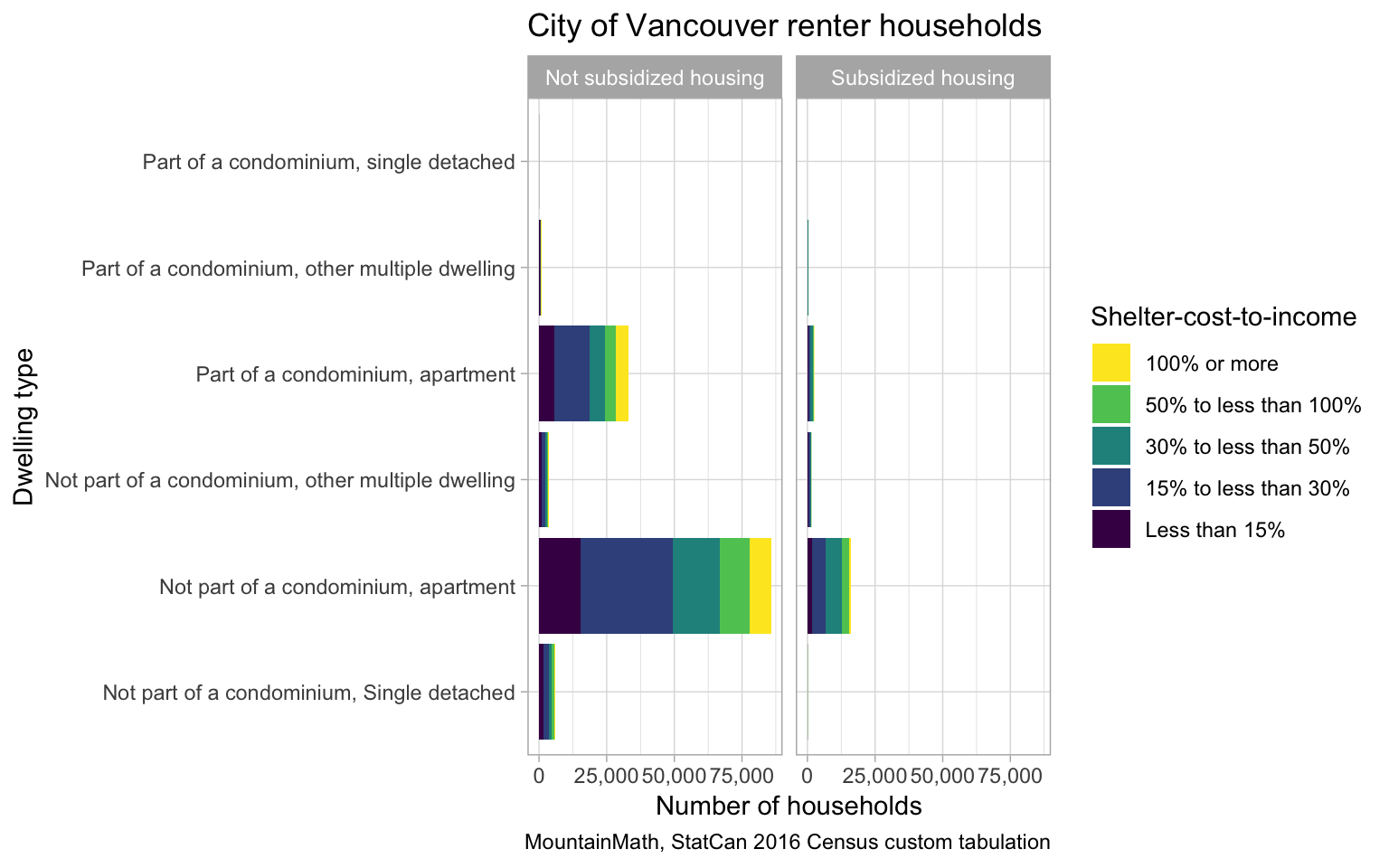

The ‘apartment’ category here captures apartments, either below 5 storeys or 5 storeys and above, as well as the census category ‘duplex’, which captures main units or suites in suited single family homes. We see that this category dominates the rental dwellings in Vancouver, with condo apartments a distant second place.

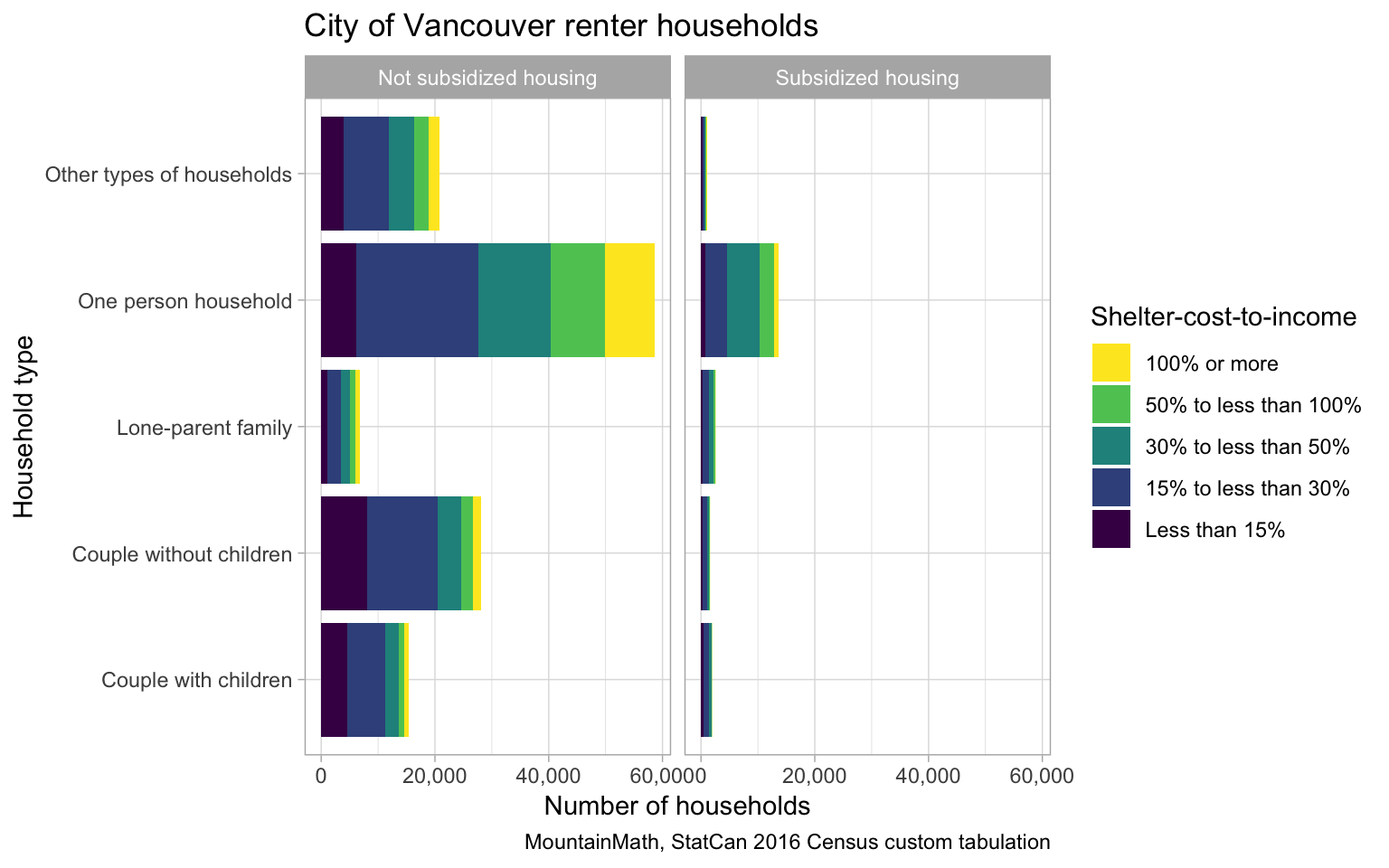

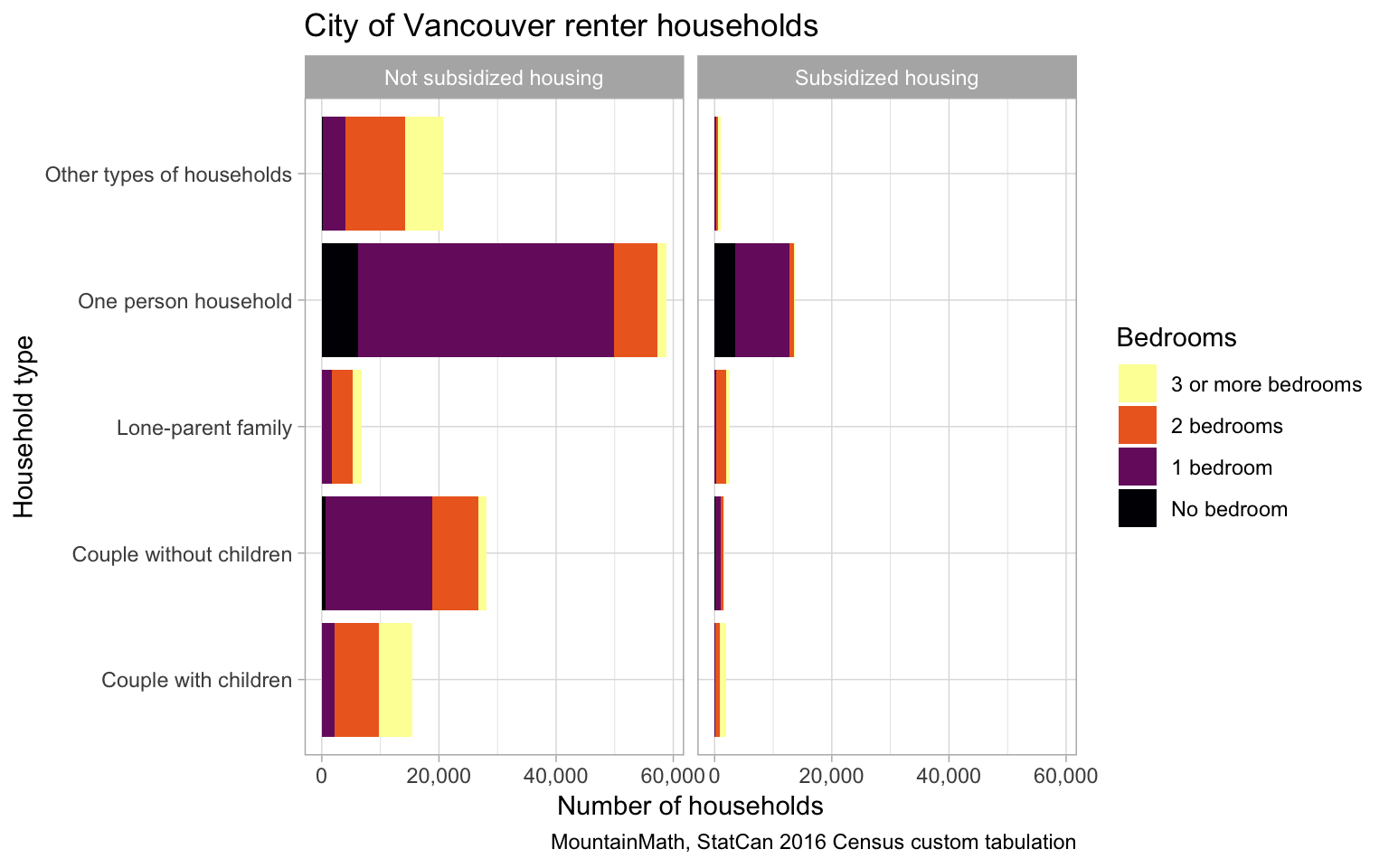

Lastly we can check what kind of households are renting.

Almost half of all renter households are one-person households. To better understand what kind of rentals these different family types are in we can look at the number of bedrooms.

The couple with children and lone parent households in 1 bedroom units likely feel crowded, and they won’t meet the CMHC suitability metric. Subsidized housing is better at right-sizing, which is usually part of their mandate.

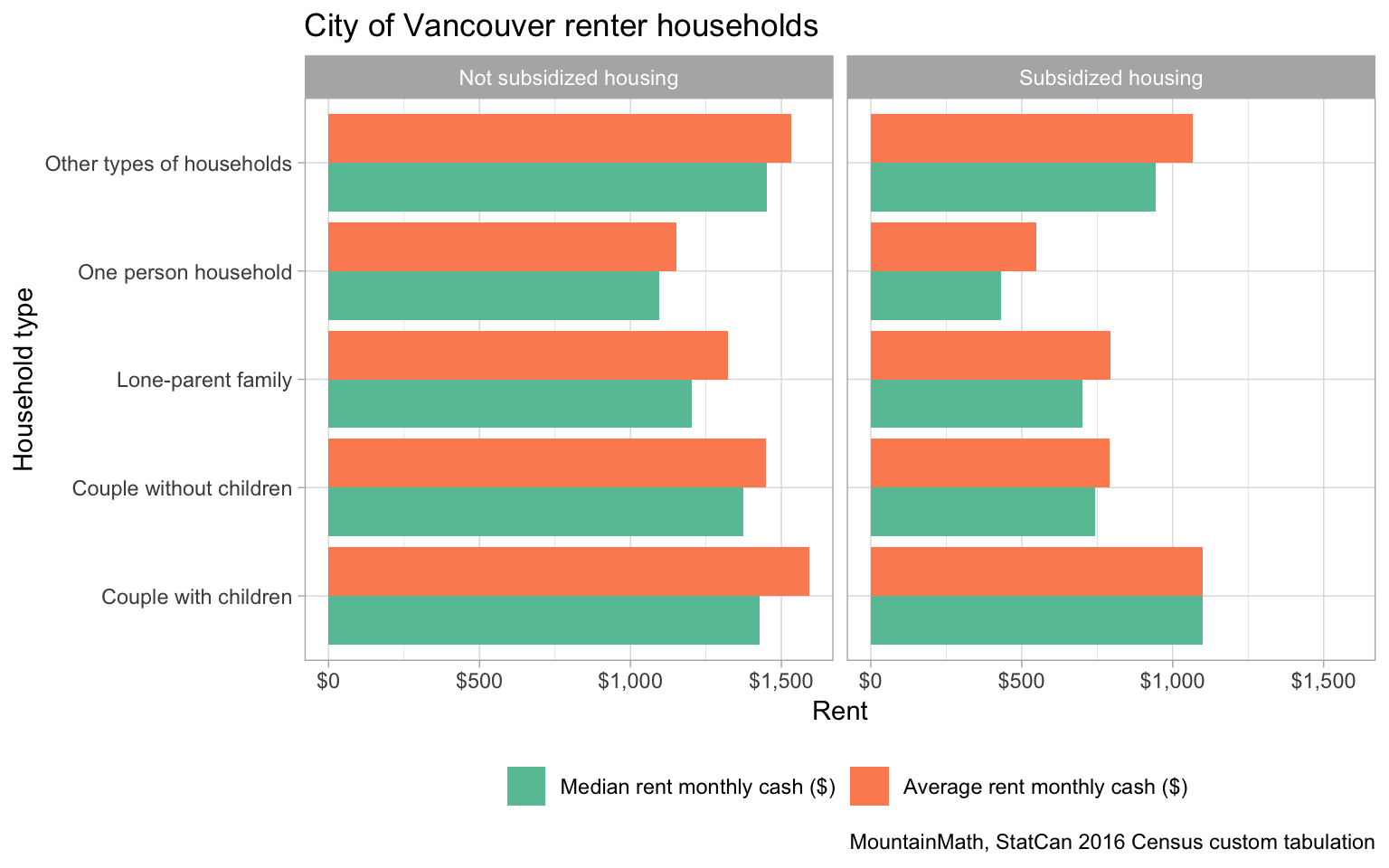

Lastly we can look at household rents, in this case excluding utilities unless utilities were already folded into the rents.

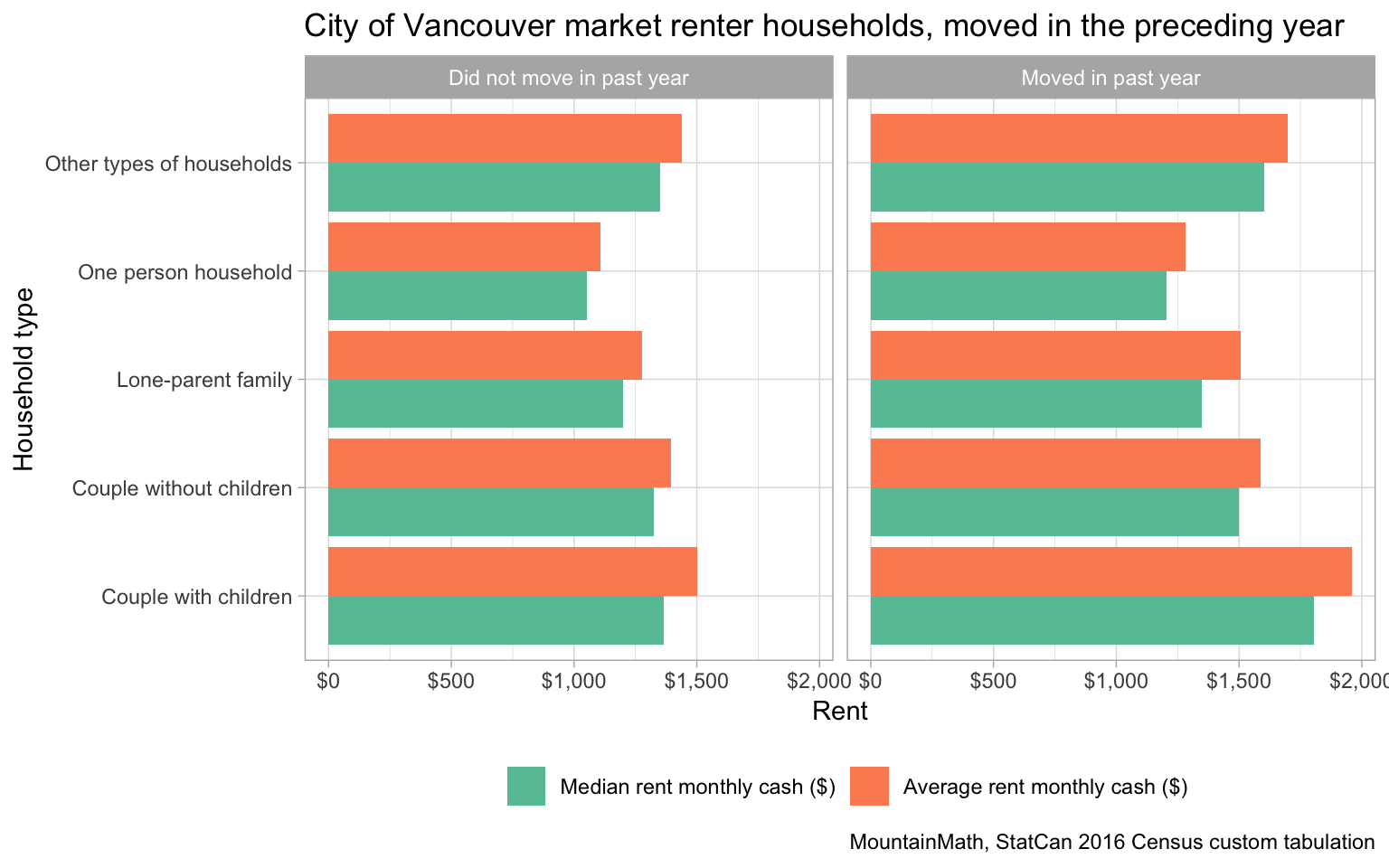

As expected, rents in subsidized units tend to be substantially lower. Averages out-perform medians, indicating the skewedness of the rent distribution. People that have been renting for a while typically pay significantly lower rents than people that moved into their rental unit more recently. We have explored the moving penalty, the ratio between turnover and in-place rents, before. To gain further insight, we can separate out households that have moved into their rental unit within the year preceding the census from those that did not.

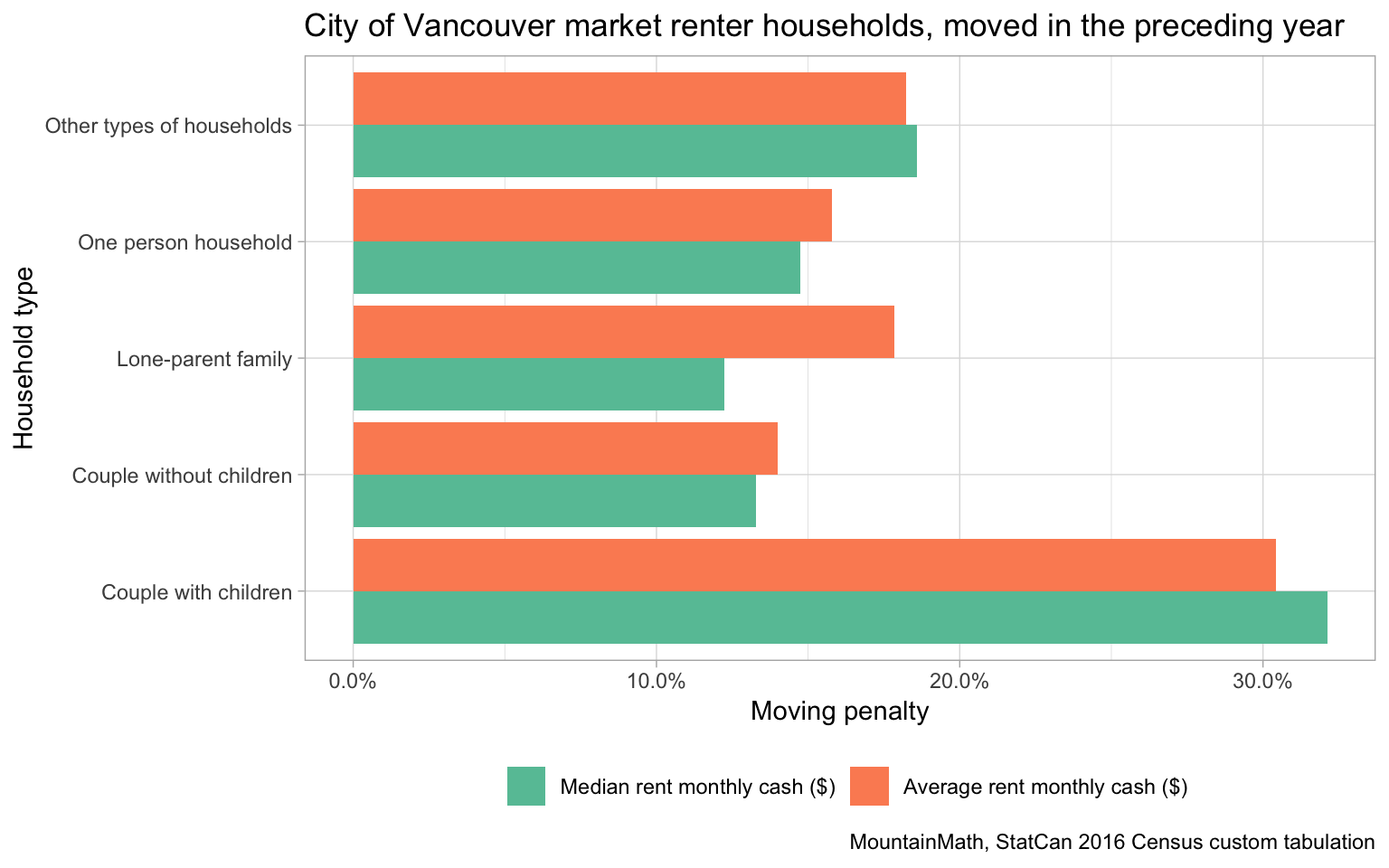

To bring this out more clearly we can compute the moving penalty, the rent increase that people that did not move in the past year would have experienced if they had moved.

This highlights to what degree couple with children families in particular are stuck in their current living arrangements, although the moving penalty is quite steep overall, and the overall ratios square quite nicely with our previous work on this using CMHC Rms data, indicating that a similar moving penalty persisted in 2018 two years after the census.

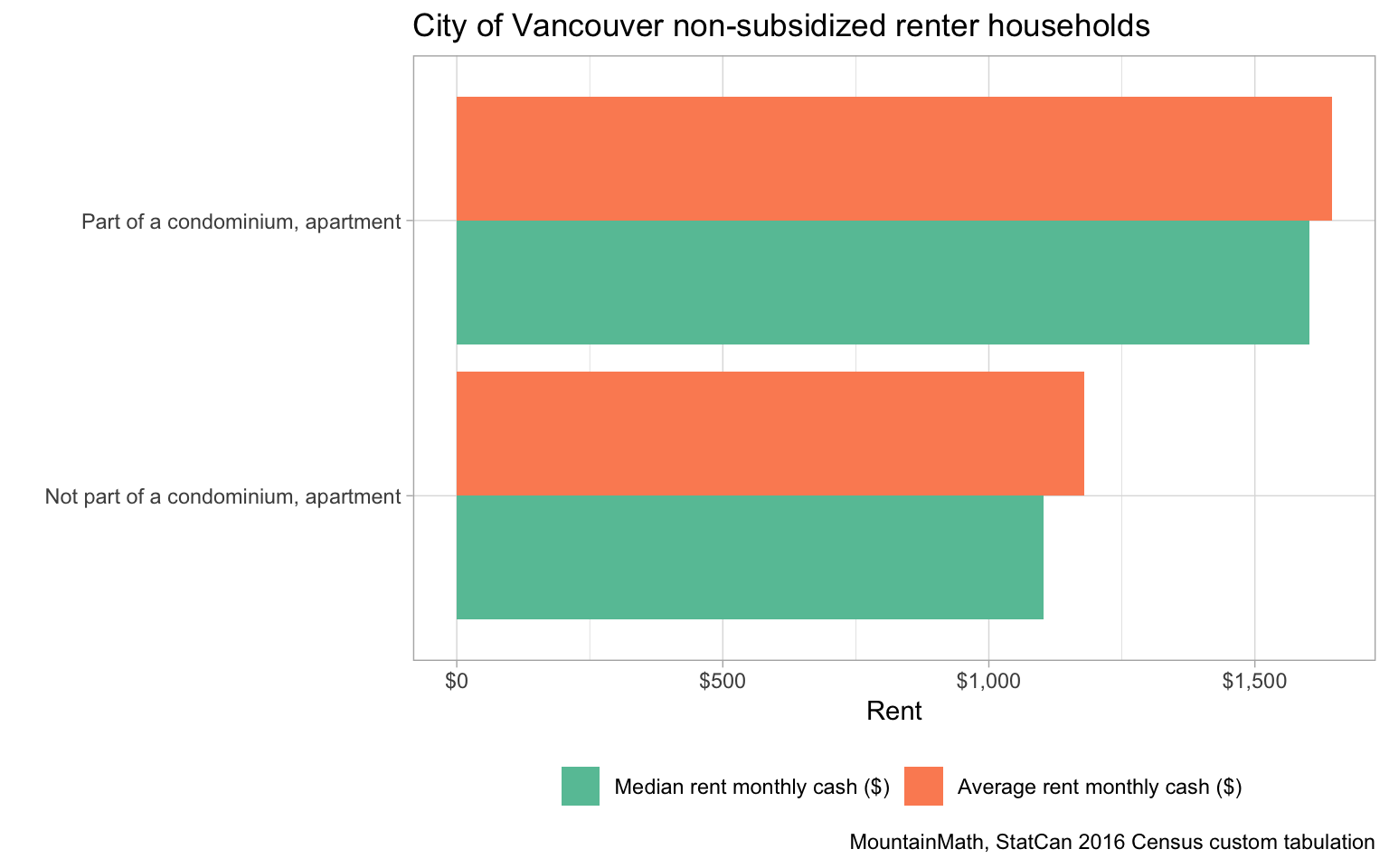

To round things off we want to compare condo apartments to non-condo apartment rents.

This shows how non-condo apartments (including single family with secondary suites) tend to rent for less than condo apartments. However, surveys show that renters are generally prepared to pay more for living in purpose built rental than on the secondary condo market, all else being equal. Unfortunately we don’t have granular enough data to filter by location and building age as proxies for quality to test this.

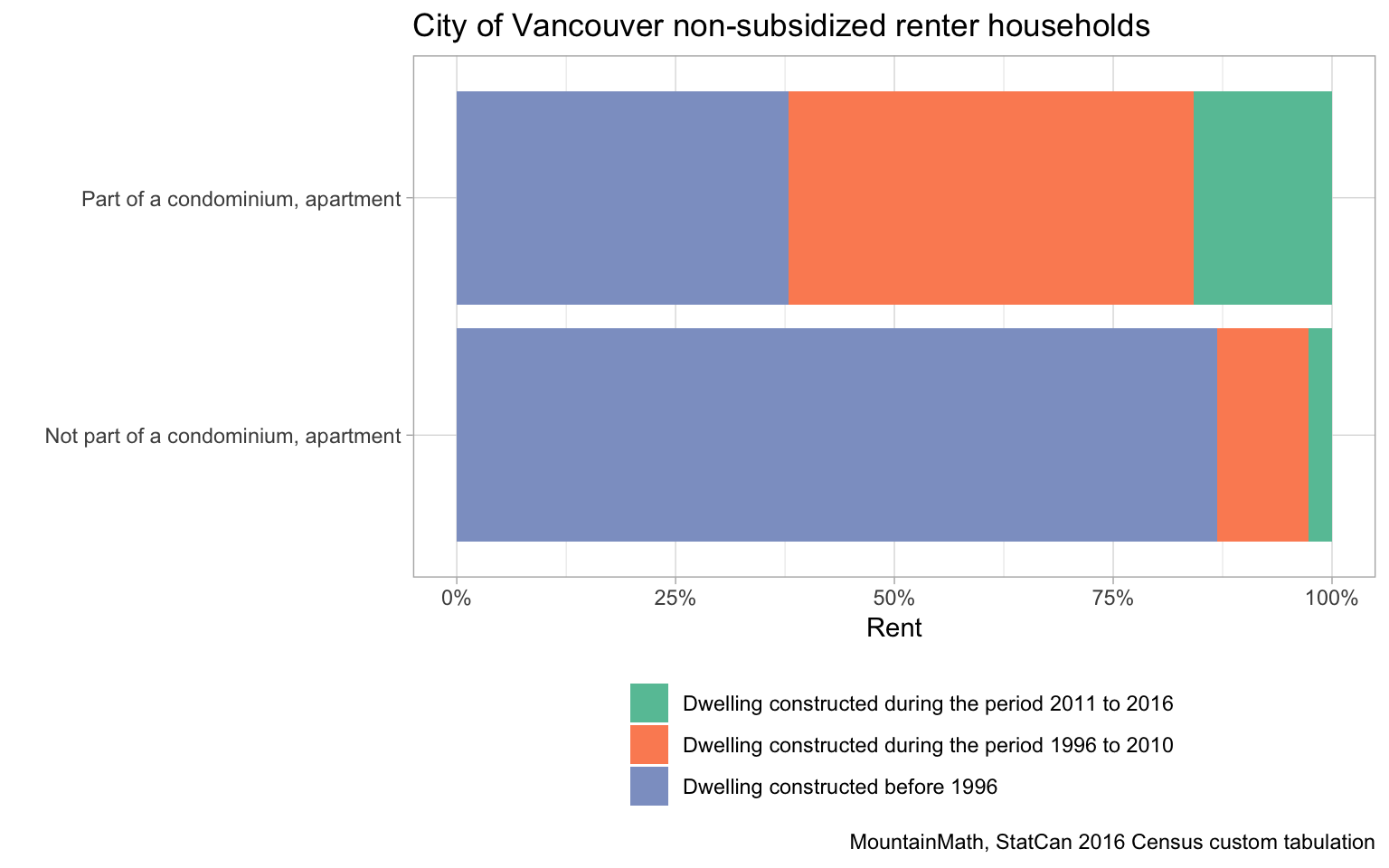

What we can do here is key out very rough building ages.

This shows that the condo apartments skew much more recent than non-stratified market rental buildings, confirming our suspicion that the rent differential may be due to dwelling quality. It would be interesting to get finer data on location and building age, as well as separate out secondary suites from non-condo apartment rentals, to better understand what drives the difference in attractiveness of these dwelling units that get reflected in the market rents they are able to fetch.

Update (March 4, 2018)

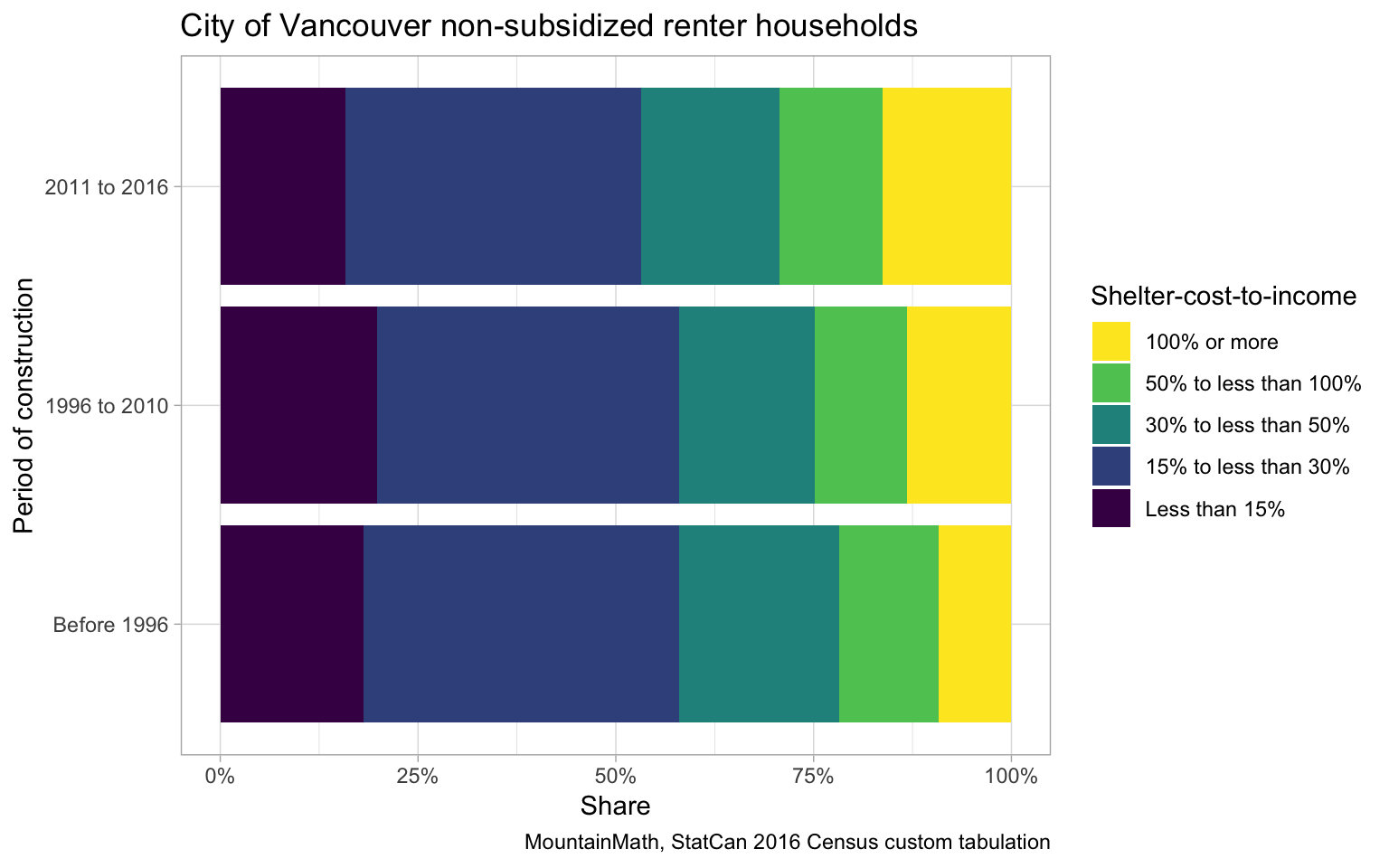

I just saw an interesting question about newer vs older rental units, and how affordability, as measured by shelter-cost-to-income ratios, relate to building age.

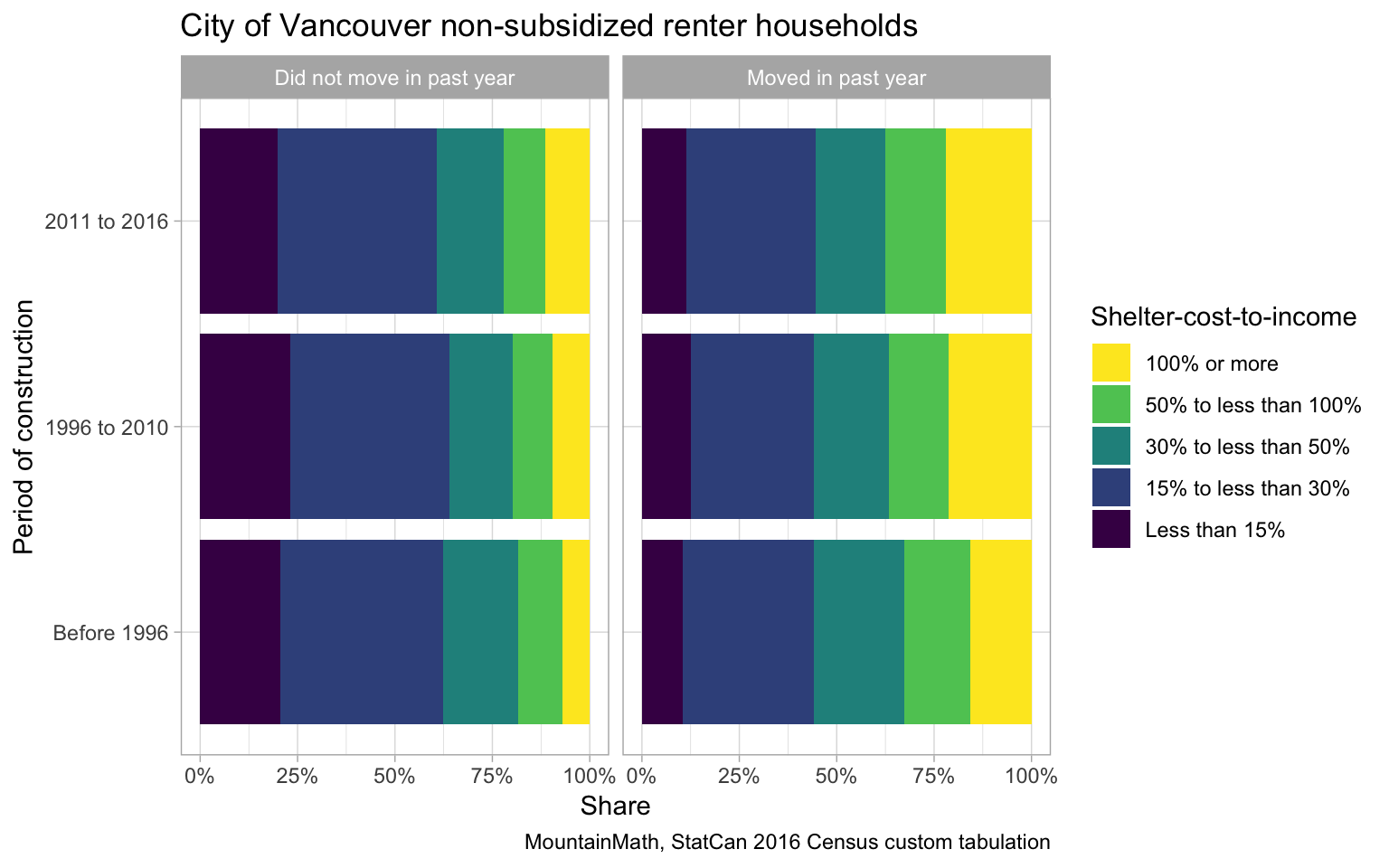

And indeed there is a tendency of older stock having higher shares of households below the 30% shelter-cost-to-income cutoff. Looking at discussions on the moving penalty higher up, we suspect that at least some of this effect is due to newer dwelling units have a higher share of people that moved in recently, and thus not benefiting as much from rent control as renters in older units. We can check this by looking at households that did and did not move in the previous year separately.

This shows that for people that have moved within the past year the share of people paying less than 30% of income on housing is independent of the age of the building, although the share of people paying very high shares of income on housing is lower in the pre-1996 stock. The picture for households that did not move in the preceding year aligns a little better than before taking out the recent movers, but still shows some variation. It would be good to come back to this again with a cross tabulation using the mobility 5 instead of the mobility 1 variable.

Next steps

This post opens up more questions than it answers. Hopefully I will find the time to add to this by adding posts on different aspects, or maybe others pick things up and continue from here. As always, the code is available on GitHub, although I am currently not at liberty to share some of the custom tabulations used in this post.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{vancouver-renters.2019,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Vancouver Renters},

date = {2019-02-15},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-02-15-vancouver-renters/},

langid = {en}

}