District wide enrolment in VSB schools has been on a steady decline for over a decade. At the same time there are areas within the VSB that have seen strong growth in children requiring new schools to get built.

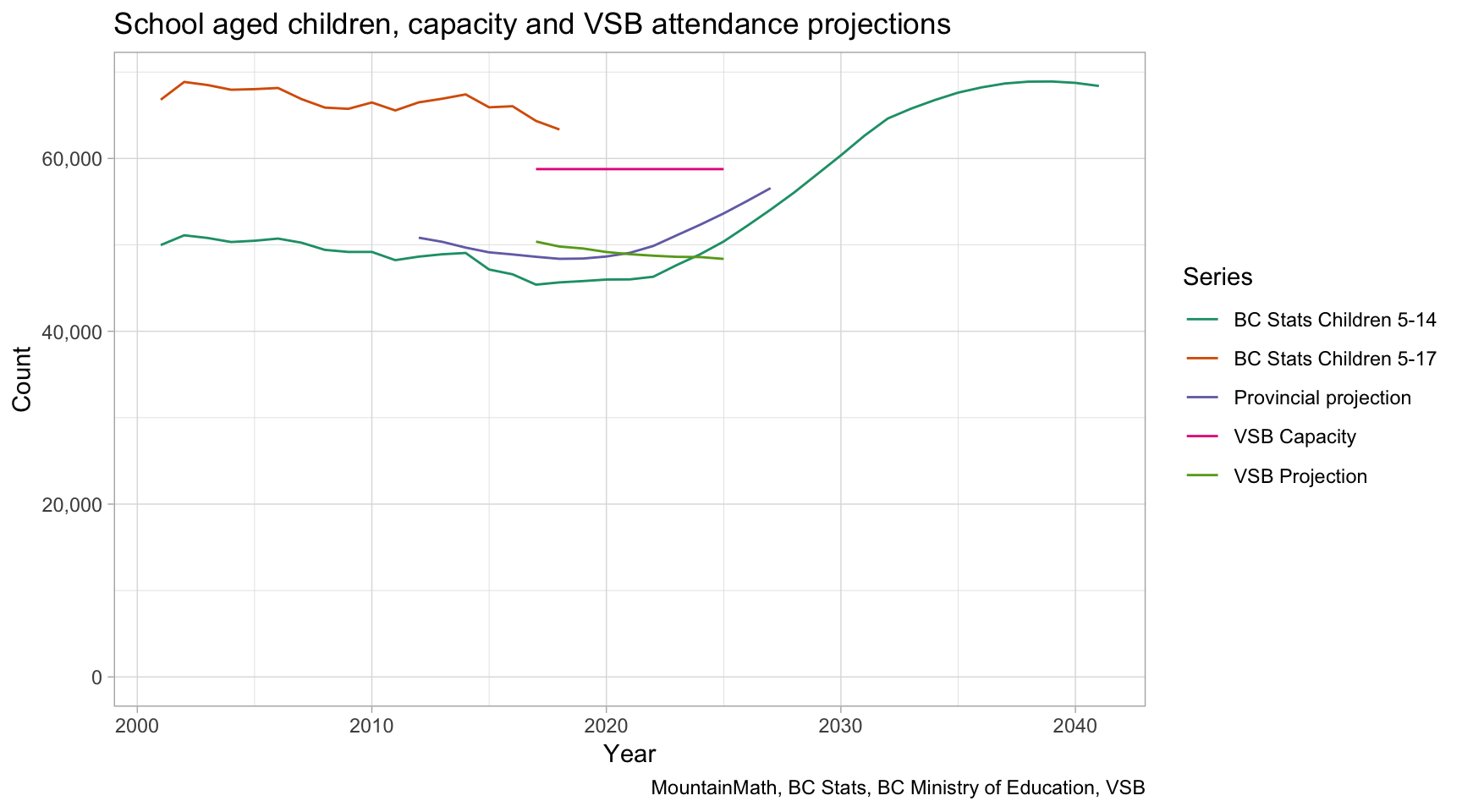

Looking at a couple of time series for the VSB District we can see where the problem lies. The children aged 5-17 living in the VSB District is estimated by BC Stats based on a number of data sources, and the number has been declining over the years. We can see a similar decline in provincial (projection) data, which lists actual numbers for past years. The provincial enrolment data is somewhat lower than the VSB projections that reflect actual enrolment for the current year, we are not sure what causes this. Possible explanations are that provincial enrolment counts don’t count children below school age, and we are not sure if they count international students.

The most interesting feature is the very different trends of Ministry of Education and internal VSB enrolment projections, with the former starting to turn from declining to rising around 2019, whereas the internal VSB projections show a steady decline.

Projections

Projections are hard, and always wrong, some more than others. In cases where different methods give significantly different results, and it is important to get fairly accurate estimates for facility planning, the usual procedure would be to read through the methodology of the diverging models to better understand what causes the discrepancy and make informed decisions. Unfortunately this is not possible in this case. While the Ministry’s projections are based on the BC Stats models, which is described in depth on the BC Stats webesite, VSB internal projections are based on private black box methods by Barager systems.

The BC Stats projection are publicly available for 5-year age brackets, and we show the 5-14 year old age group and we can see how the change lines up nicely with the change in enrolment projections done by the Ministry.

While overall enrolment is a primary driver for the enrolment issues faced by VSB, it is not the only one. We also need to pay attention to the shifting distribution of students within VSB, which has lead to some schools overcrowding, and new schools being added, while other schools have been losing students.

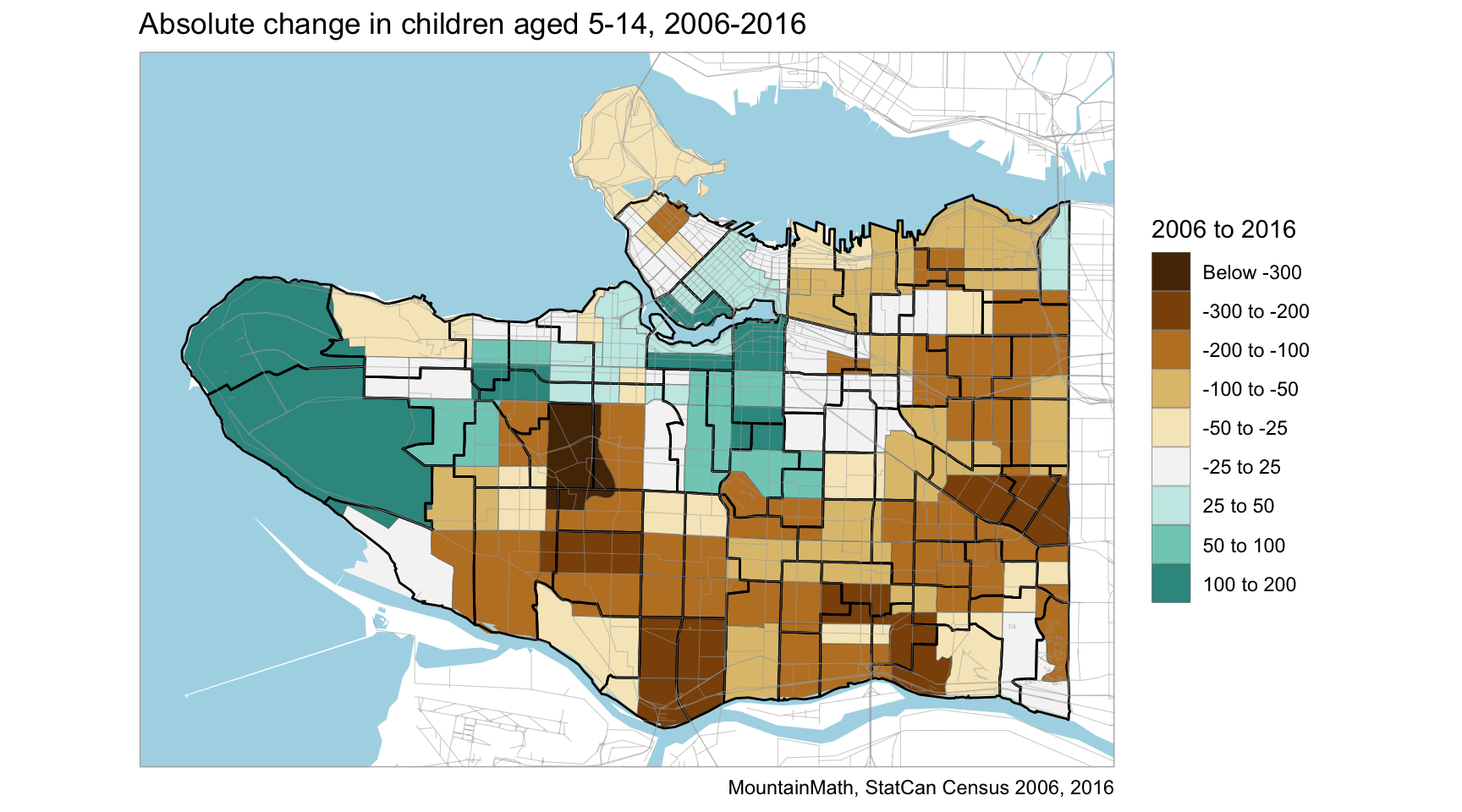

Census data can give a good indication of the changing spatial patterns.

This shows quite clearly the problems VSB is facing, which demand for schools building up in some areas, and dropping in others.

We see that the number of children increased in Downtown, Olympic Village and Mount Pleasant along the Cambie Corridor, as well as UBC and pockets in Dunbar and Point Gray, and to a lesser extent in Kits. Other areas ranged from stable to very strong decreases, most pronounced in Arbutus ridge. It would be interesting to dig down further into what is driving these geographic patterns. Just taking a cursory look we see that traditional single family neighbourhoods are losing children, which we have observed before.

We have overlaid the catchment areas, which gives some indication which schools are struggling to attract students, and which are turning students away. To better understand why VSB had such a hard time dealing with areas experience student growth like Yaletown or Olympic Village, it’s instructional to take a closer look at one example.

UBC schools, a case study

I am most familiar with the schools near UBC, since that’s where my son goes. A little under five years ago Norma Rose Point opened, relieving a lot of the pressures on University Hill Elementary and Secondary schools. At the time, University Hill Elementary was reduced from K-7 to K-5, leading to lots of changes at the school from letting go of teachers to removal of portables that housed an after-school program. This was done based on enrolment projections done at the time. Past summer, four years after the downsizing of the school to K-5, the VSB board voted to change UHill Elementary back to K-7, based on the current enrolment realities. At the same time, the board also voted to postpone plans for the South Campus elementary school for at least a couple of years.

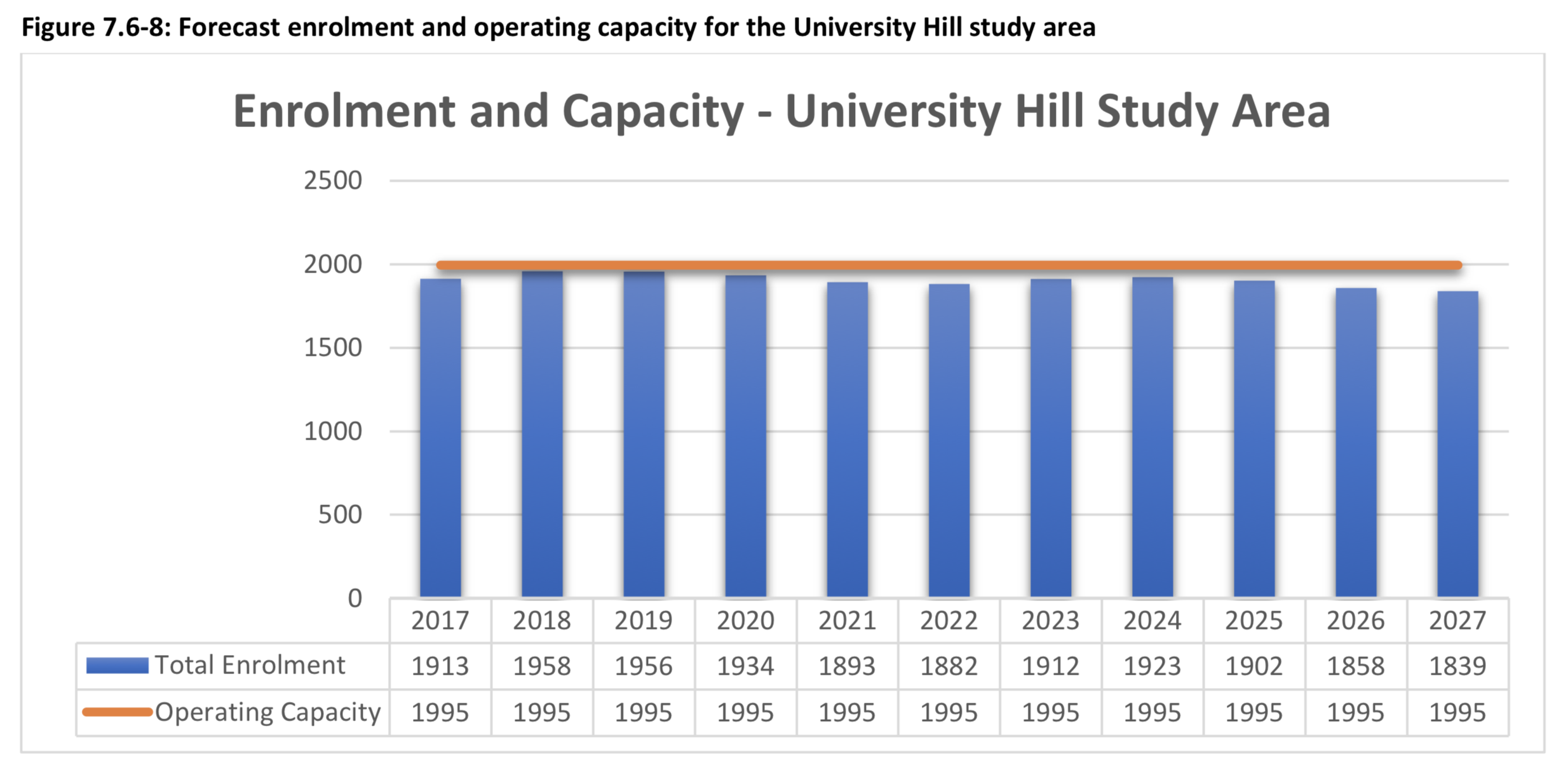

The enrolment and capacity situation is summed up in the Long Range Facilities Plan on page 64 and following.

The enrolment and capacity situation is summed up in the Long Range Facilities Plan on page 64 and following.

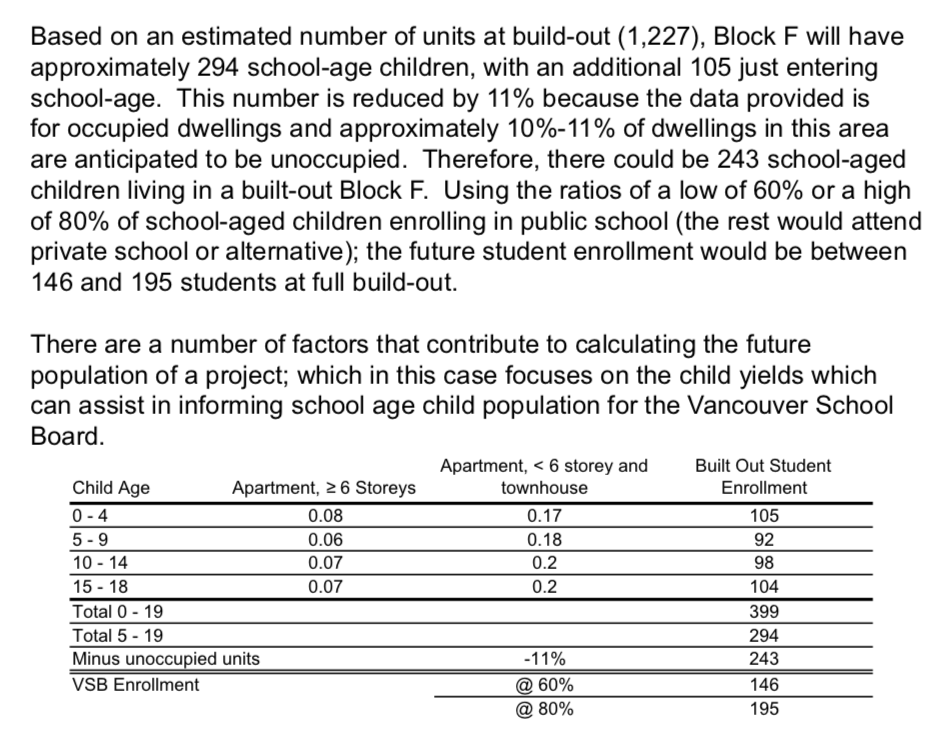

We see that the combined three schools in the area are operating at capacity, which is not a problem since VSB projects that enrolment will decline. UHill Secondary also has a good portion of international students that could be moved to other schools if the need arises, so there is a little more buffer than the graph suggests. However, anyone familiar with the university neighbourhoods will find the notion that enrolment will decline curious. The problem is that VSB does not take new developments like Block F into consideration, even though the developer did provide projections on the children population based on unit mix of the development and extrapolation from census counts for similar unit mix, coming up with around 170 additional children once built-out.

At the same time, development continues at the usual pace in South Campus, with several large multi-family buildings completing every year. This makes it really hard to understand the VSB insistence on working based on the assumption of declining future enrolment for the UBC area schools.

At the same time it explains well what went wrong with planning regarding Yaletown and the Olympic Village, VSB is really bad at accounting for new development. These stresses leads to increased cross-boundary traffic. Which can be quite difficult for students, especially in geographically isolated areas like the UBC schools.

School enrolment patterns

The VSB has made detailed cross-boundary data available, which gives us the ability to better understand the pressures each school faces and how children and parents work around these constraints.

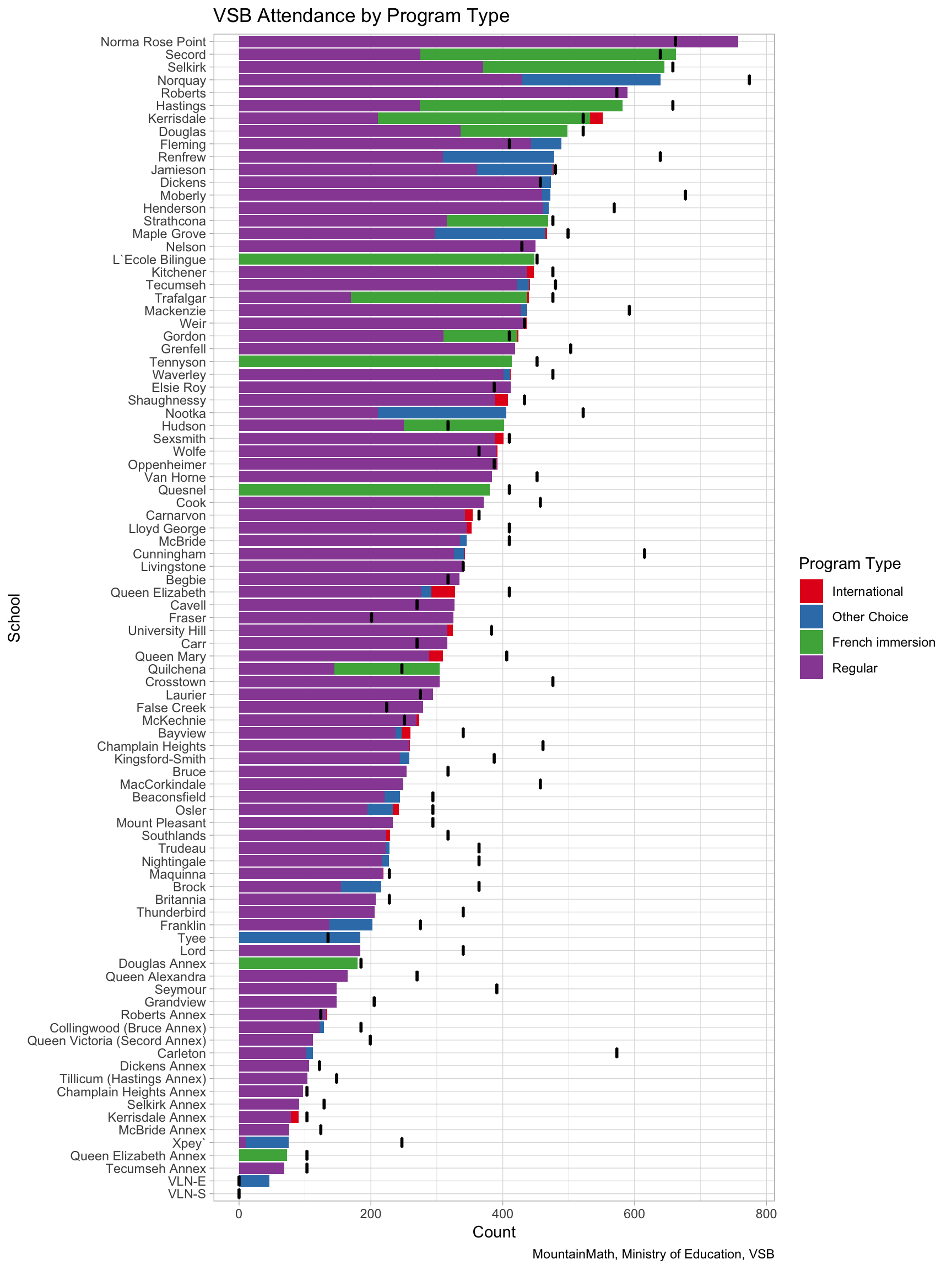

The VSB cross-boundary data allows to split enrolment into regular and “non-regular” programs, which includes district programs and international programs. The Ministry makes data on enrolment by program type available, and mixing the two one can get a good picture of enrolment patterns in schools. One caveat is that the two datasets may not line up perfectly due to timing of when they were pulled and some students dropping out or entering into the VSB program mid-year. In our data there are four schools where the total number of enrolled students differ by one between the two datasets, which gives us some confidence that the discrepancy is not large and it makes sense to merge the data from the two different sources.

The black bars indicate the capacity of each of the schools, showing most schools operating below capacity, some by a lot.

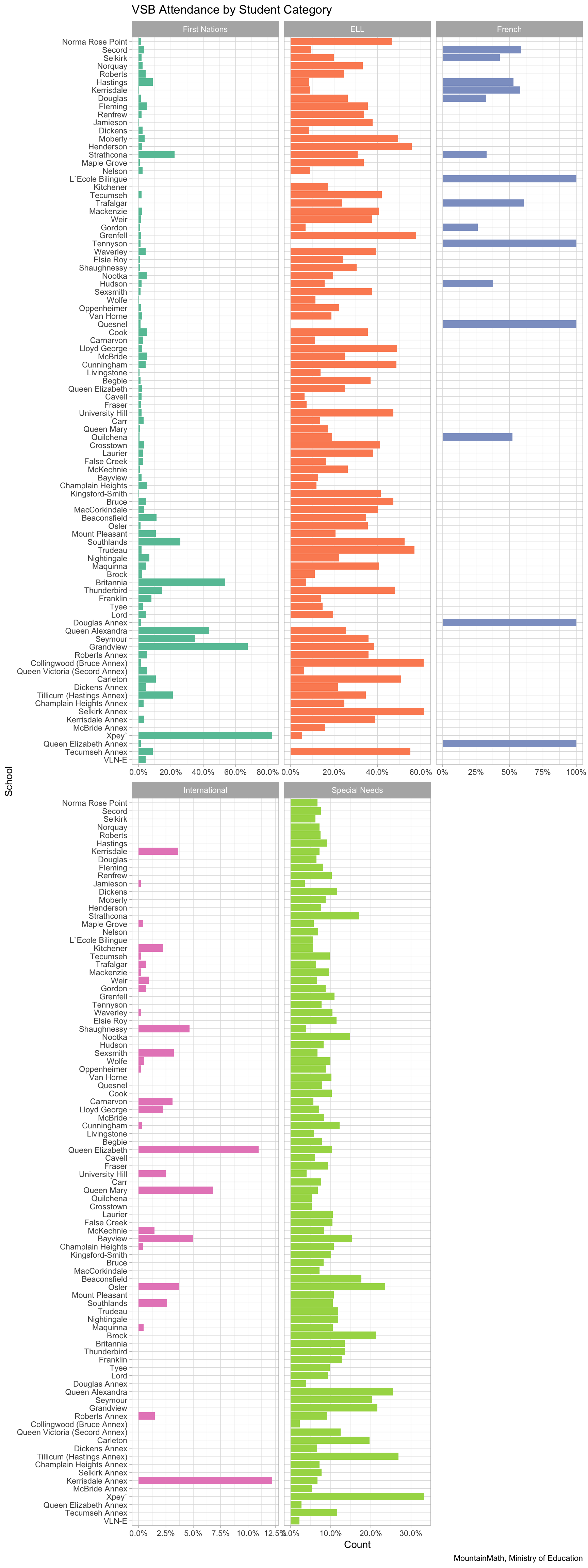

We can similarly explore other within-school metrics.

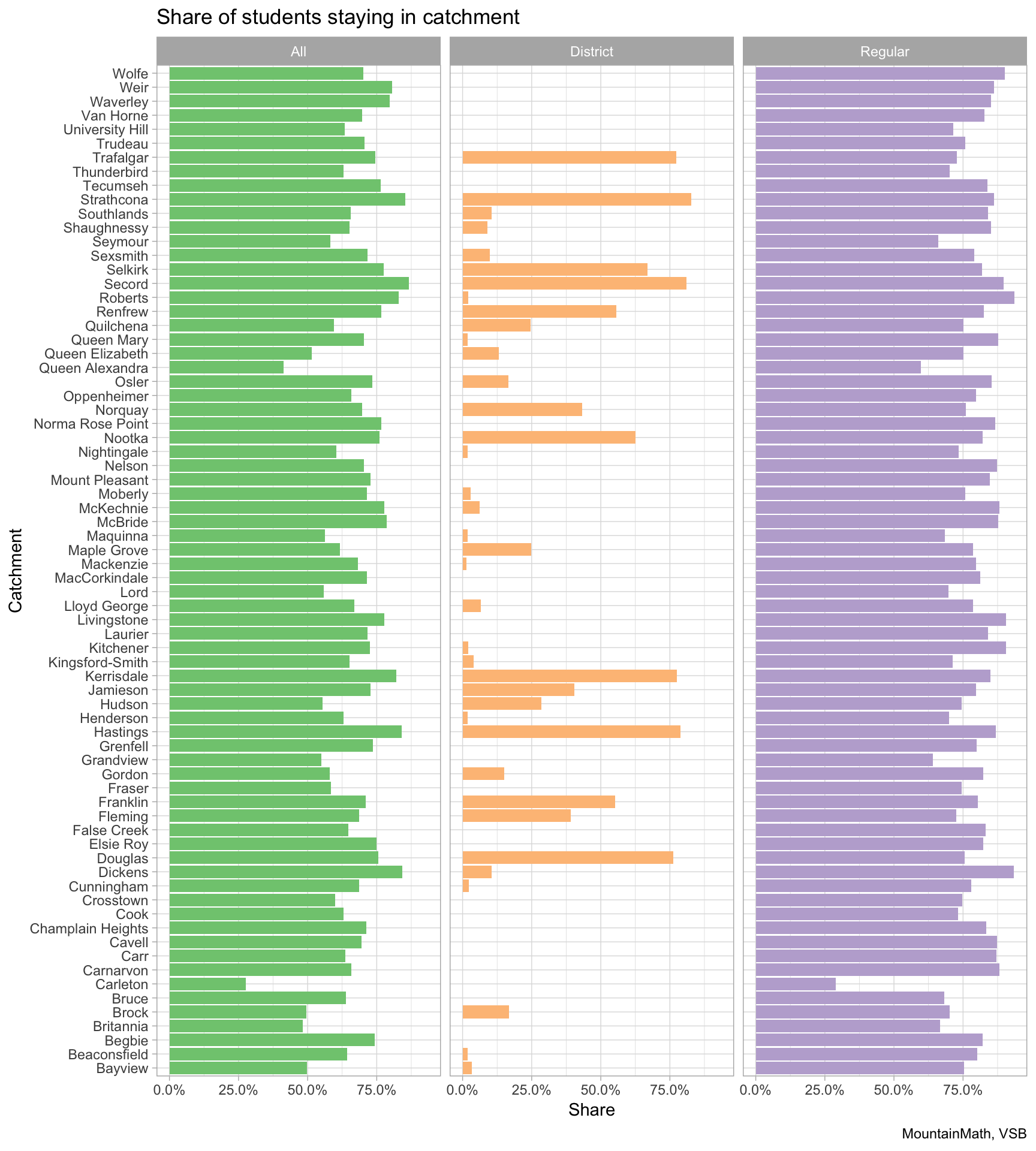

While enrolment has been the main metric employed by the VSB in school closure discussions, in-catchment population is another metric that should be of interest. The idea of neighbourhood schools is still important to many, including myself. This gets complicated by the abundance of district programs, some of which give priority to in-catchment children while others don’t. It also raises the question about Annexes, which might be best treated as extensions of the main catchment schools in terms of their capacity.

Looking at all students by catchment, we see that some of the variance in the rates of attendance in catchment schools (including annexes) is explained by varying proportion of students attending out-of-catchment district programs. Moreover, some catchment schools have in-house district programs, which students in that catchment seem to prefer over travelling to out-of-catchment district programs. This speaks to in-school district programs being quite attractive to students and their parents.

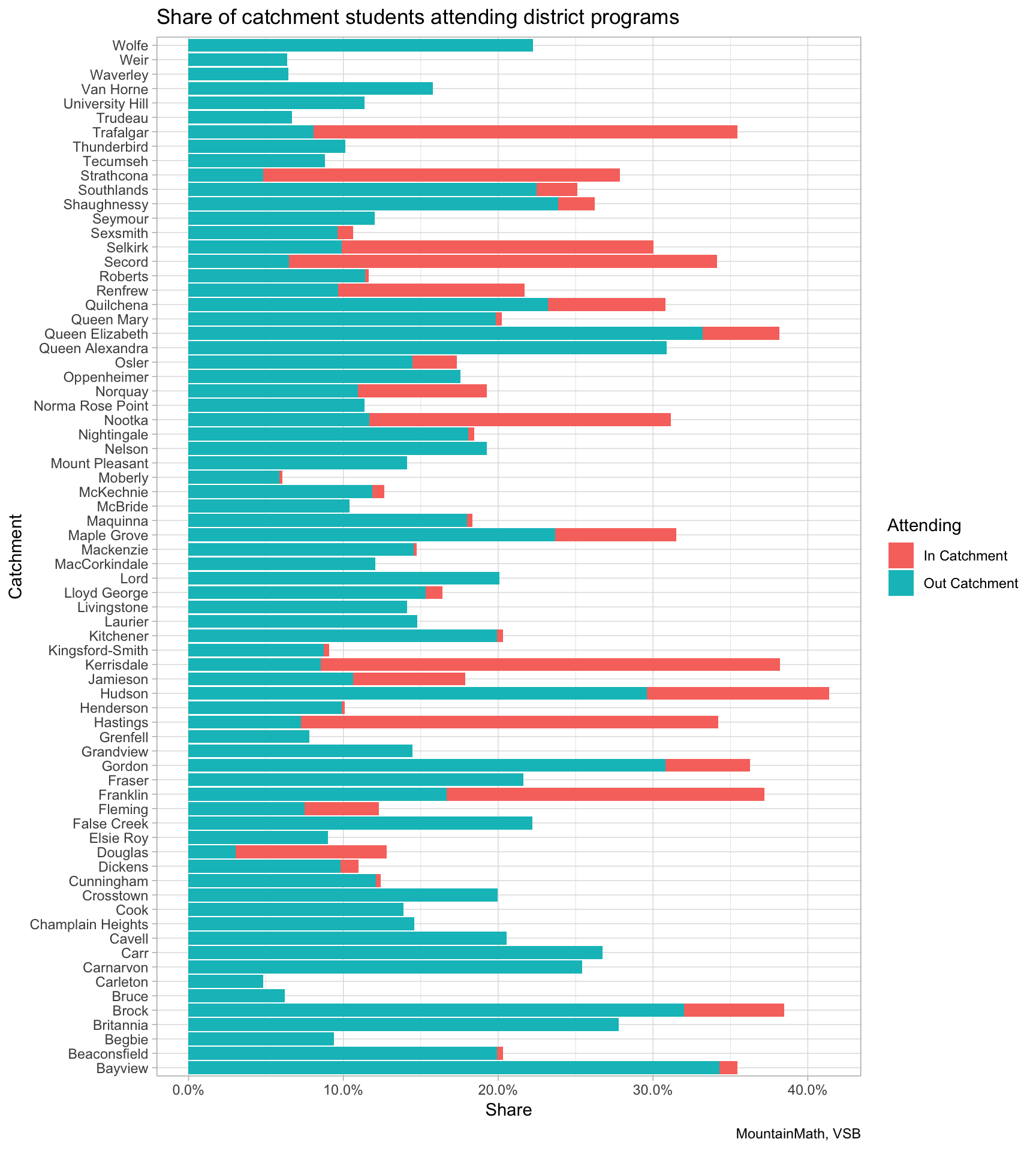

We can investigate this further by looking at the share of students in each catchment that attend district programs.

Some of the higher rates of children attending district programs can be explained by district programs in catchment schools, but that still leaves significant variation unexplained.

Cross-boundary

Of most interest to me are the cross-boundary movements of children. Here it is useful to distinguish movement to district programs like French Immersion from movements to regular programs.

Before we get started, it’s useful to first get a better overview of the cross-boundary movements. This interactive map allows one way to explore this, hovering over a school shows the origins and destinations of net flows, with the net flow arcs coloured red at their origins and green at their destinations. Net flows substantially under-state total flows. For example, there are 69 students in the University Hill Elementary catchment at attend Norma Rose Point and 64 children in the Norma Rose Point catchment that attend University Hill Elementary, resulting in a net flow of 5 students from University Hill Elementary catchment attending Norma Rose Point.

Here we peg the origins at the “catchment schools” coloured in blue on the map, with “annex schools” in black and “district program schools” in green. For “annex schools” we chose to count students with the catchment of the associated school as “in catchment” and won’t show them as flows from the catchment school to the annex. The radio buttons allow to show all flows, or just flows to regular programs or flows to district programs. We put the origin for students coming from out of district a little to the south-west of Vancouver. We don’t have data on students within VSB that attend schools in other districts.

Armed with this data, we can start to answer some basic questions about cross-boundary flows. Most importantly, what is the extent of net east-west flows?

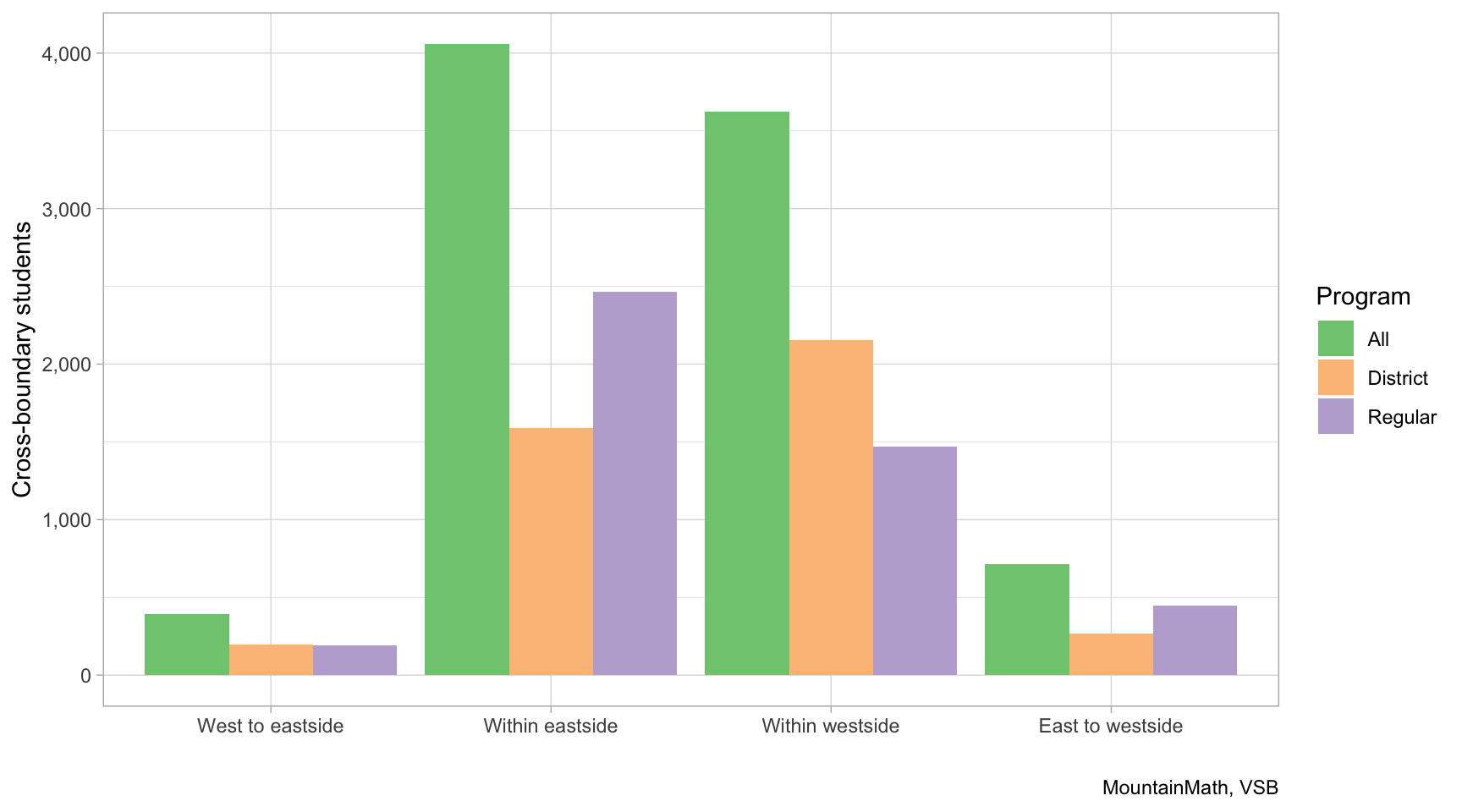

We use two different ways to quantify east-west flows. One is a simple metric that looks at movements relative to the eastside/westside division that to this day plays a role in Vancouver’s psyche and remains visible in demographic data.

This crude but psychologically important metric shows that while most movement is contained within each east/west side of the city, we do see stronger flows from eastside to westside than vice versa.

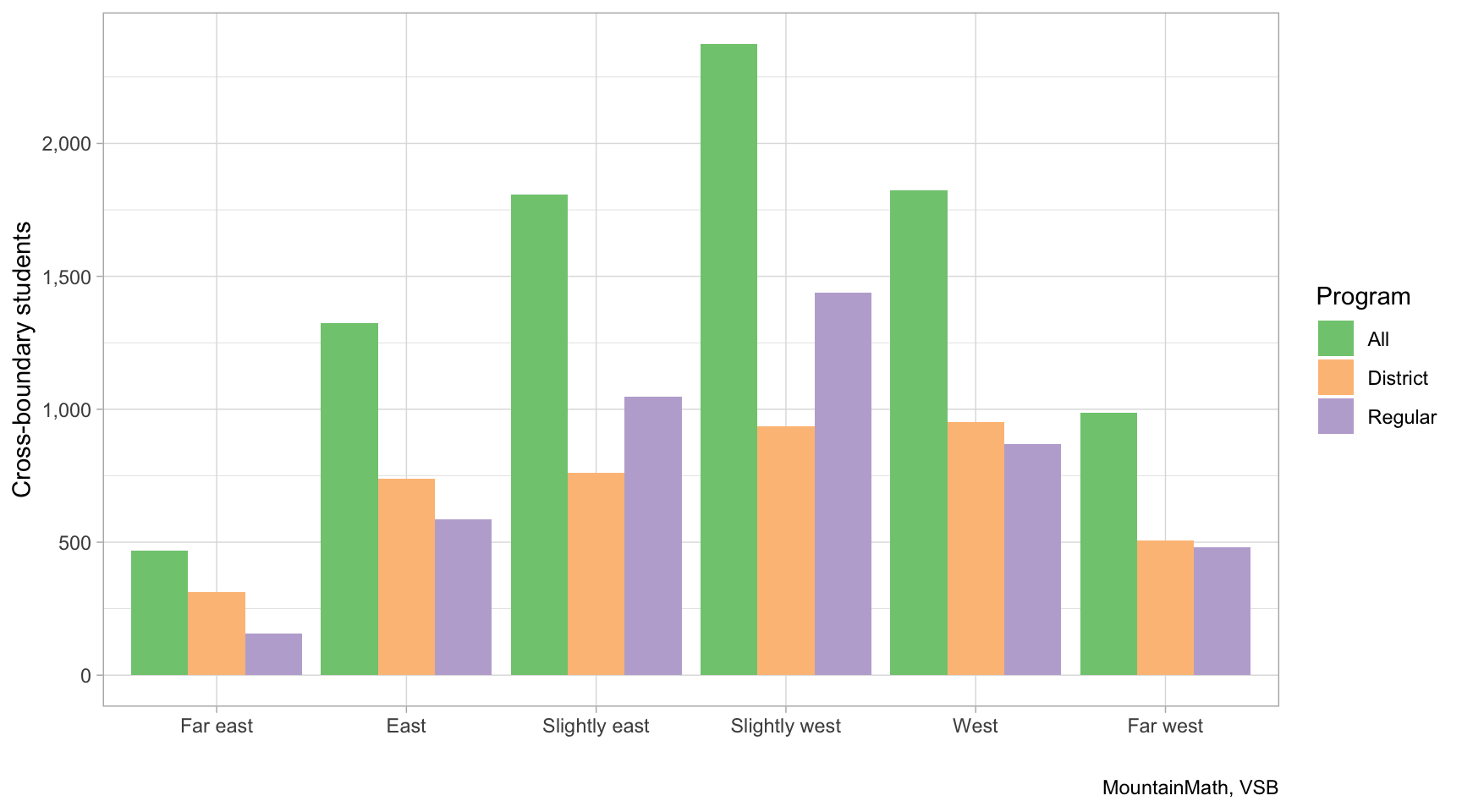

Next we quantify the general tendency to move east or west, focusing exclusively on the east-west component of moves and labelling moves farther than 2.5km along that component as “far” and moves closer than 1km as “near”.

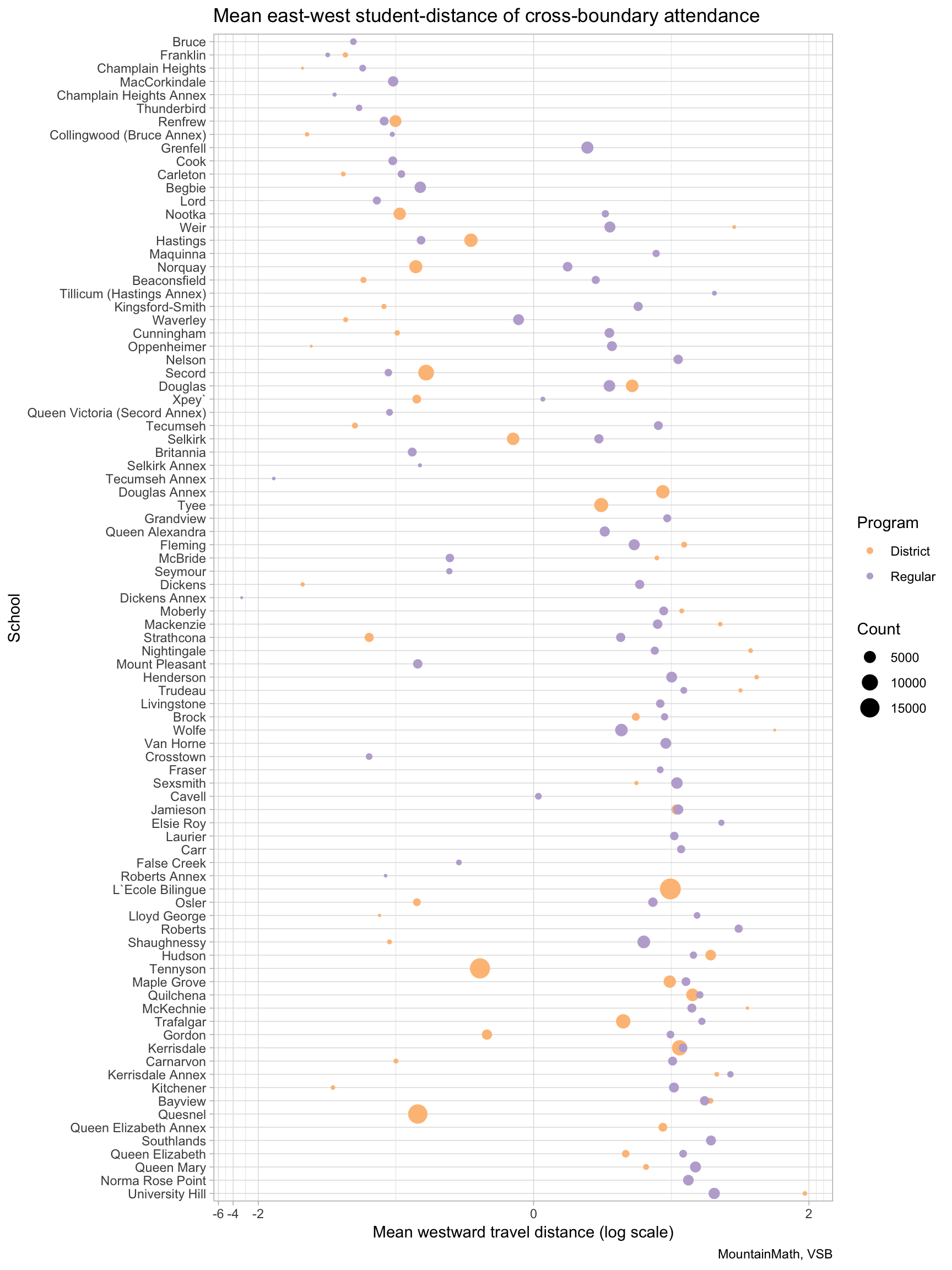

This cements the notion that there is indeed an east-to-west migration in the cross-boundary data. It is visible in district programs as well as regular programs, and most pronounced in “slight” east-west movements. Another way to look at this is to take the mean east-west person distance travelled to each school.

This helps identify which schools see the heaviest east-west traffic, and which schools see the reverse. The schools are ordered from east-most to west-most. The east-most schools can only attract cross-boundary traffic from the west, so their mean westward travel distance has to be negative. It’s remarkable how quickly schools located fairly east start to attract a net influx of westbound traffic.

One caveat here is that we don’t know the locations of the students within each catchment, but compute this based on the assumption that students are located at their catchment schools. However we should expect this to roughly average out in most cases.

Next steps

This post turned out a little more rambling than usual, mostly because it was written in small chunks over a period of several weeks. Big thanks to all the people helping when I tried to make sense of the data, as well as related discussions in this long twitter thread. And sincere apologies to everyone that got tagged into this for having to endure it.

There are lot of related questions that one could go after, but this post is already too long. We might pick this up again and drill down into related questions. Also, we only looked at elementary schools, at some point it would be good re-run this for secondary schools.

As usual, the code for the analysis is available on GitHub for anyone interested in looking into details or expanding on it.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{vsb-x-boundary.2019,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {VSB {X-Boundary}},

date = {2019-04-15},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-04-15-vsb-x-boundary/},

langid = {en}

}