(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

What are the best metrics for understanding if a given place has enough housing, just the right amount, or too much? Whether you’re a potential renter or buyer or an analyst or policymaker, the answer really depends on what you’re looking for.

For potential renters and buyers, if you can’t find what you’re looking for and/or it’s not in your price range, then there’s not enough housing. If you can find it, then there’s just the right amount. When is there too much housing? Mostly if you’re already comfortably housed, but concerned about changes to your neighbourhood and/or you’re looking to maximize the price you can get for selling your housing. So we can root a set of foundational answers to questions about housing supply in peoples’ direct experiences interacting with the housing market. We can also extend this to non-market housing. If there are people on the waitlist, there’s not enough non-market housing (note: there are ALWAYS people on the waitlist and we definitely need more non-market housing).

But decisions about whether we have enough housing aren’t actually left to people interacting directly with housing markets. Most people can’t add much to the supply of housing by themselves. Housing has become exceptionally technical, and a vast slew of regulations now prevent most self-building except in informal sectors (in Vancouver most notably the subdivision of existing dwellings into suites, only a minority of which comply with building codes and have a permit). Instead most decisions about how much housing we have are produced via a combination of developers working through their financial models in conjunction with planners, regulators, and politicians working with tight existing constraints on what can be built where. Interestingly, both the comfortably housed and those looking to maximize their prices for selling housing DO get a voice. Why? They tend to be the ones electing (and speaking directly to) local politicians. This group notably includes local developers, who are both actively engaged in maximizing the prices they can get for selling housing and actively engaged in local politics (if you think market developers are unambiguously pro-supply, think again).

So how do we know if we have enough housing in a given place? Or, since the answer always depends upon the perspective, how do we hear from potential residents (including renters and buyers) about whether THEY have enough housing? Their voices are the ones that tend to get left out of debates. Usually, to the extent their voices are heard at all, it’s through some set of metrics informing decision-makers. So let’s return to metrics, because different metrics tell us different things!

Ideally decision-makers consider metrics with specific goals in mind: do we have enough housing in a given place for what purpose? Are we interested in enough housing to meet demand, preserve affordability, or address need? Enough to promote the right kind of growth? Enough to support transit, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote urban vitality? Or perhaps we’re worried about too much housing to support our preferred sales price, keep out the wrong kind of people, preserve our favourite aesthetic, maintain green space, or just generally keep our neighbourhood the way we like it? Being clear about these goals is helpful, insofar as they set the criteria for which metrics can provide meaningful answers. If we can decide on our criteria, then we still have to figure out the right metric. Let’s start by looking at the four common elements that make up most metrics:

- Dwellings

- Money

- People

- Land

These are the things we tend to track with our metrics for whether or not we have enough housing, just the right amount, or too much. Dwellings are housing. If we want to figure out if we have enough, then we definitely need to keep track of dwellings. Of note, dwellings can also be differentiated by square footage, number of bedrooms, and related characteristics. Money is an expression of desire, weighted by wealth and/or income (and hence also inherently unequal). People are bodies, variously disposed to live together and share space. Both money and people move around, unlike most dwellings, which are fixed in place. Land is how we fix dwellings in place, and can support various numbers of dwellings. By virtue of fixing dwellings in place, land also defines various kinds of places we might be concerned about: e.g. neighbourhoods, cities, and metropolitan areas. Places are connected to one another: what happens Downtown has an impact on nearby neighbourhoods (e.g. Kitsilano), just as what happens in the City of Vancouver has effects on what happens in the City of Surrey. As a result, metrics should pay careful attention both to place of interest and interconnection between places. In the background, fitting these elements together, we also want to keep in mind that time matters to how we construct metrics.

The key metrics we tend to track often involve just two of the elements above, measured at varying scales of aggregation, places, and times. We can provide a quick and dirty guide to the different questions answered by the key metrics we use to measure if we have enough housing or too much as well as the underlying logistical mechanism guiding our inquiries.

| Class of Metric | Q. Do we have enough / too much housing to… | Logistical Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Money per Dwelling | Preserve Affordability | Market Allocation / Inequality |

| People per Dwelling | Fit people into dwelling units | Rationing / Sharing Rules |

| Dwelling per Land | Support Urbanism / Reduce Env. Impact | Rationing / Sharing Rules (via zoning) |

How we define elements matters to how the metrics work, as does how we incorporate time and the level of aggregation (individuals, households, census tracts, cities, metro areas). We’ll keep coming back to these throughout, often with reference to examples from Vancouver, the metro area we know best, but it’s helpful to start by keeping things simple.

Money per Dwelling (a.k.a. price)

Perhaps the most obvious way to bring these elements together is by asking how much dwellings cost. Given the persistence of market allocation for housing, there will always be enough housing to meet demand… at some price. That’s because the price mechanism sets prices at where demand curves and supply curves meet. Put differently, the demand for $1 dwellings is practically limitless. The demand for $100 million dwellings is practically zero (so far). In between, there’s a demand curve specifying how many dwellings would sell at what price. On the supply side, self-interested owners would rarely sell dwellings if they could only sell them for $1. But they’d probably sell as many as they could get away with if they could sell them for $100 million. In between there’s a supply curve specifying how many dwellings will be sold at what price. The market pricing mechanism moves prices toward equilibrium where demand and supply curves meet. This is the stuff of basic economic analysis (brought to you by a mathematician and a sociologist).

How about if you don’t just want to meet demand, but you want to meet it at a particular price? Maybe you want the market to meet a certain affordability threshold for a certain kind of dwelling? Let’s define this better: do we have enough housing if we want the average two bedroom dwelling priced at $250,000? In some places (e.g. Edmonton), this isn’t far off the mark. There’s enough housing there relative to demand that two bedroom dwellings sell for about $250,000. In other places (e.g. Vancouver), there’s not enough two bedroom dwellings to go around to everyone who might want them at that price, so they’re bid up to a far higher price. It would take the addition of a lot more dwellings to bring prices down to $250,000. So if that’s where you want prices to go, then there is definitely not enough housing.

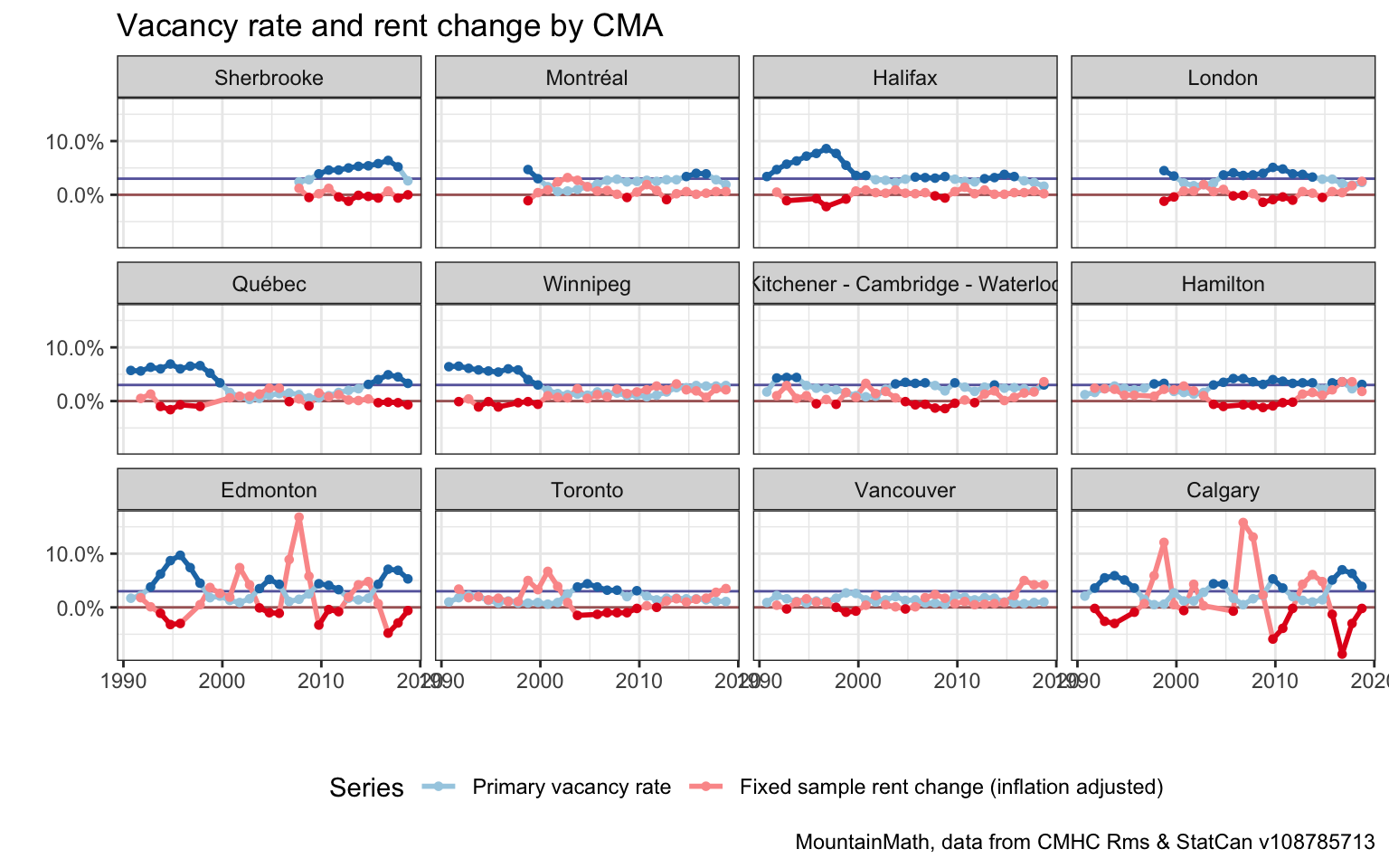

The same general dynamics apply to the market pricing mechanism for apartment rents. Landlords respond to their understanding of local supply and demand when setting their asking rents. The longer their apartments stay on the market without being rented, the more likely they are to lower their asking rents accordingly. Vacancy rates measure the supply of apartments for rent. Correspondingly, the negative correlation between vacancy rates and rent change is very strong. As vacancy rates go up, rents come down. Here’s a comparison by metropolitan area in Canada.

Say you want to ensure average rents for two bedroom apartments are affordable, at about $1,200/mo (again, around the rent level of Edmonton, vacancy rate around 5%). The takeaway from the above would appear to be that if you want to lower rents to this level in a market like Metro Vancouver (average rent @ $1,650, asking rents much higher, vacancy rate around 1%), then you need to ensure that a lot more two bedroom apartments come on the market to rent. In short, you don’t have enough housing.

Exactly how many two bedroom apartments would you need to add to bring average two bedroom rents down to $1,200/mo in Vancouver? This is a tricky (and worthy) question to answer. It would require knowing the shape of the demand curve (made up by knowing how many apartments would be rented at each rent from, say $1/mo to $1 million/mo). It would be difficult to figure this out, even if we could ask everyone in Vancouver what rent they’d be willing to pay for a two bedroom apartment. Why? Two reasons: 1) at lower rent points, some people might be willing to pay for multiple two bedroom apartments (rich people do all kinds of odd things, and when we use price as our metric, the whims of the wealthy matter more than the needs of the poor); 2) we should almost certainly assume that there are a lot of people living outside of Vancouver (including former residents) who would love to move here if they could find a two bedroom apartment for $1,200/mo. They only get a vote in how much housing gets built through their influence on the demand curve. Otherwise they don’t get heard at all. So it’s difficult to tell just how many two bedroom apartments we would need to add to bring Metro Vancouver rents down to $1,200/mo.

Another way to set a metric is to set an ideal vacancy rate instead of a specific rent. Vacancy rate targeting was explicitly mentioned by several candidates in the last City of Vancouver civic election. Inflation-adjusted rents tend to fall when vacancy rates rise above 3%. Setting a vacancy rate target of 4% or 5% will work to deflate rents.

In general, if your goal in asking if a place has enough housing is to preserve the affordability of market housing, then prices (or rental vacancy rates) should be your metric. If prices are higher (or lower) then you want them to be, then you should work to add to (or reduce) the supply of housing accordingly.

But how do we add to the supply of housing? Generally the most important way to add supply is to build more housing. It’s what builders do. But it’s worth noting that if they want to build more housing, builders get stuck in the middle of even more demand and supply curves. Labour, materials, and (most variably) land all influence the costs of constructing new housing. Just like buyers and sellers in the housing market, builders also watch price signals, and they tend to build when they think they can sell the housing they construct for a significantly higher price than they pay to purchase labour, materials, and land, with the difference equal to profit. The Minimum Profitable Production Cost (MPPC), or the minimum cost to bring a new unit to market, sets a hard cap on when builders have any incentive at all to try and add housing. As a result, it also provides a lower bound on the price of new market housing. And this minimum cost rises as density increases and construction becomes more involved and expensive (the minimum profitable production cost of new rental housing in Vancouver is currently too high for market developers to offer new two bedroom apartments at $1,200 market rents). Not surprisingly, holding other characteristics constant, new housing always tends to be more expensive than old housing. As a result, when you compare new housing to old housing, it might seem like new housing is doing nothing at all to bring down prices. But when you consider that building new housing is the primary way of adding more dwellings to the market overall then you get how new housing might “soak up” some of the demand in a given market, thereby lowering the prices of older housing from where they’d otherwise be and bringing down prices overall. Of course, building new housing only adds to the total housing market to the extent that you build more new housing than you demolish, a point to which we’ll return below.

Aside from demolitions, how would one reduce the supply of housing? Generally speaking, we seldom see demolitions exceed new construction, so this doesn’t happen much. But there are a few examples we can talk through, perhaps most prominently AirBnB. In response to new profit-making incentives of AirBnB, many property owners have removed dwellings from the long-term rental market into the short-term, hotel-style market (these markets once weren’t so distinct, but they have become so over time with the passage of laws like BC’s Residential Tenancy Act). As dwellings get removed from the long-term rental market, it drives down vacancy rates and correspondingly drives up asking rents for those units remaining.

What else matters? Location, location, location. Additions and subtractions from the supply of dwellings for sale or rent don’t just have local effects. Their effects spill over into places near and far, tied together by their fixture to land and to transportation networks. For instance, the effects of building and renting out a bunch of new housing in Downtown Vancouver may be felt in asking rents in suburban Surrey. The degree to which additions of housing in one place affect rents in another is heavily dependent upon how long it takes and how much it costs to travel between them as well as to job centres and amenities. That said, some observers suggest that hyper-local “induced demand” may come in to play, meaning that new construction in Downtown Vancouver could potentially drop asking rents in suburban Surrey more than asking rents Downtown. The evidence gathered to date suggests this likely doesn’t happen much, but certainly the scale of the metric matters when thinking about how the addition of new supply affects prices and rents.

So far we’re also talking strictly about dwelling characteristics like bedrooms and size, but not about the structural type of dwellings. We can’t add more single family homes in the inner municipalities in Vancouver, so market mechanisms are constrained in terms of reducing the rent or price when we restrict ourselves to single family homes in the inner municipalities. Being very picky on location can have similar effects. Adding condos or rental properties in the downtown peninsula is more expensive than adding them in e.g. Dunbar. Adding housing in downtown requires concrete high-rise, which is substantially more expensive than 4 or 6 storey low rise which can still add significant housing in Dunbar. Providing amenities like public spaces and libraries for a growing population is also more expensive in areas that are already denser. Given demand and various constraints, it’s quite possible that the market won’t ever be able to supply rental housing at a cost that can push rents down into the $1,200/month range (or push the sale price into the $250,000 range) for a 2 bedroom apartment in Downtown Vancouver. But Surrey seems possible. Regardless, if we want to try we have clear price signals that we’d need to add a lot more 2 bedroom apartments than we have now.

Considered as a class metrics for Money per Dwelling, including prices (per dwelling, per sq ft, etc.), rents (per BR, etc.), rental vacancy rates, and sales listings, represents transactional data reflecting market pricing mechanisms. Inequality is built into these measures as a reflection of how market allocation weighs the whims of the wealthy of greater importance than the desperate desires of the poor. Correspondingly, reductions in inequality make for more egalitarian housing outcomes. Given market allocation of housing, this is the class of metrics people should turn to if they’re interested in achieving or preserving affordability. They provide the clearest path for identifying if there’s enough (or too much) housing when affordability is the criteria of interest. Of course, these metrics don’t resolve the debate between those who want prices and rents to rise (home sellers and landlords) and those who want them to come down (home buyers and renters), but at least they provide a common empirical grounding.

People per Dwelling (a.k.a. residential crowding)

People per dwelling provides a different class of metrics for thinking about whether there’s enough housing, focused on residential crowding. Fundamentally these metrics ask if there are there enough dwellings to “fit” the number of people we have in a given place. Of course, this is only a potential measure of fit when houses are mostly distributed by the market. Wealthy people probably take up way more room (and rooms) than they need, while poor people more often end up stuffed together. There are two solutions to this situation: one is to ration housing, so that extra rooms are shared around. We see this only for the small proportion of our housing stock that’s non-market housing. Market housing isn’t at all rationed according to need, but instead doled out by wealth-weighted desire (money). The other solution, far more common across North America, is to outlaw too much residential crowding via maximum occupancy codes and sharing rules. This is very common, and in the absence of rationing housing according to need this tends to lead to the exclusion of poor people altogether.

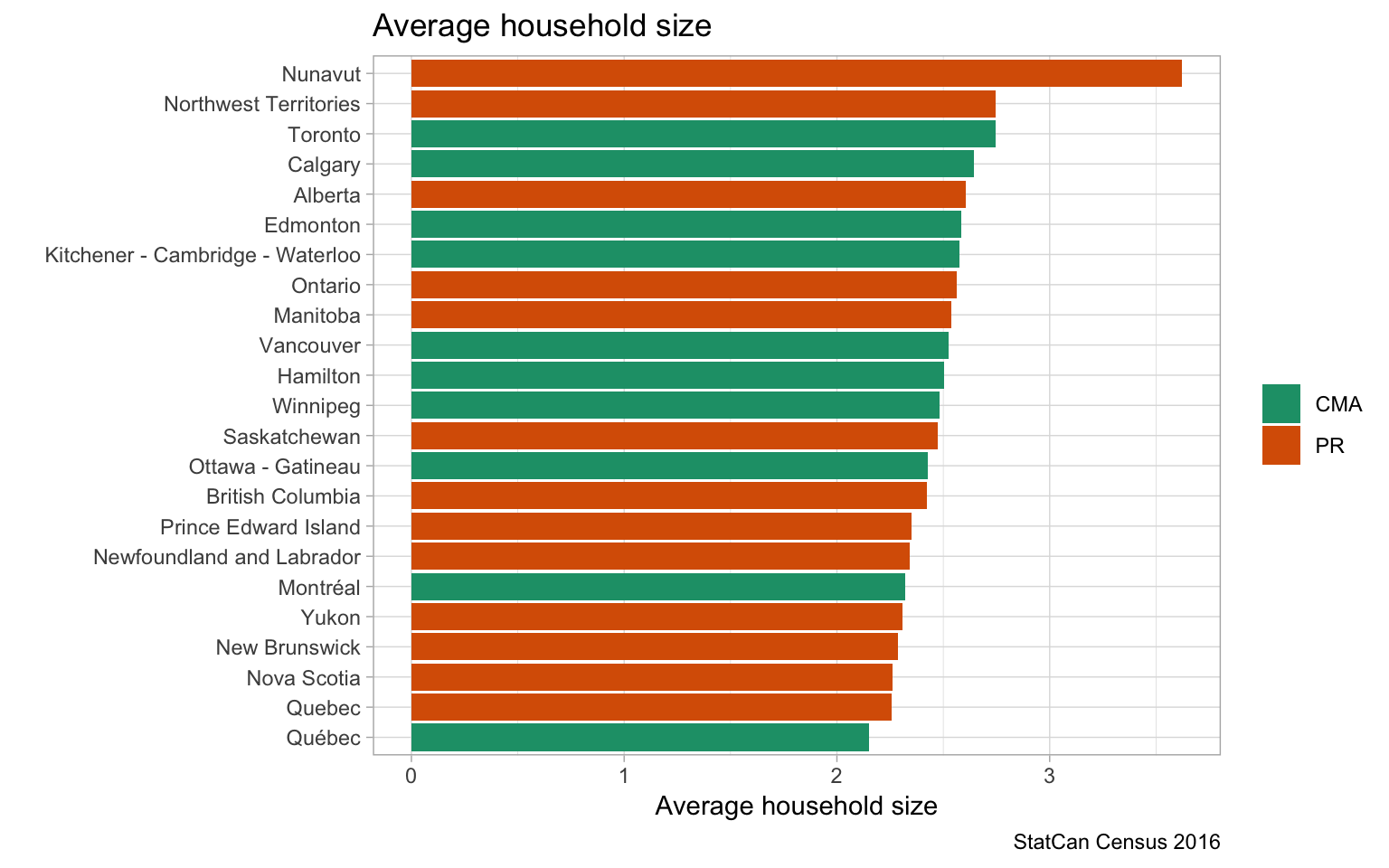

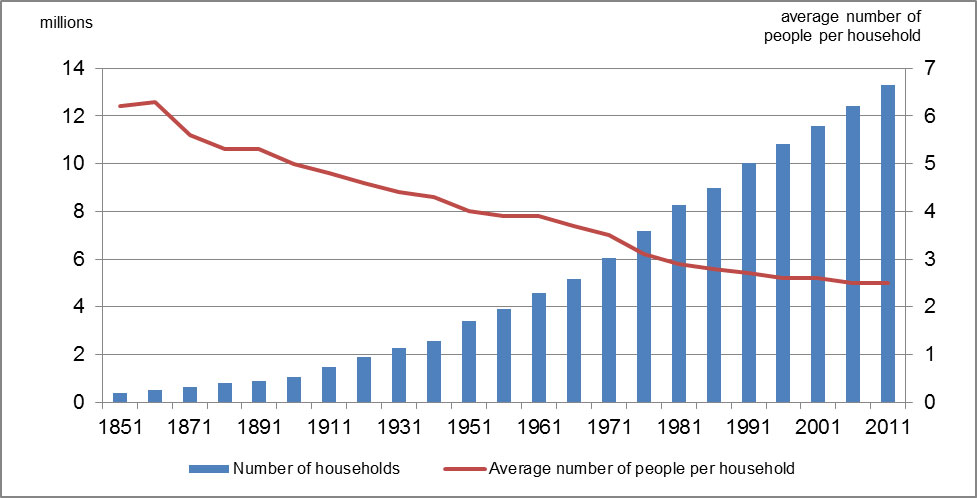

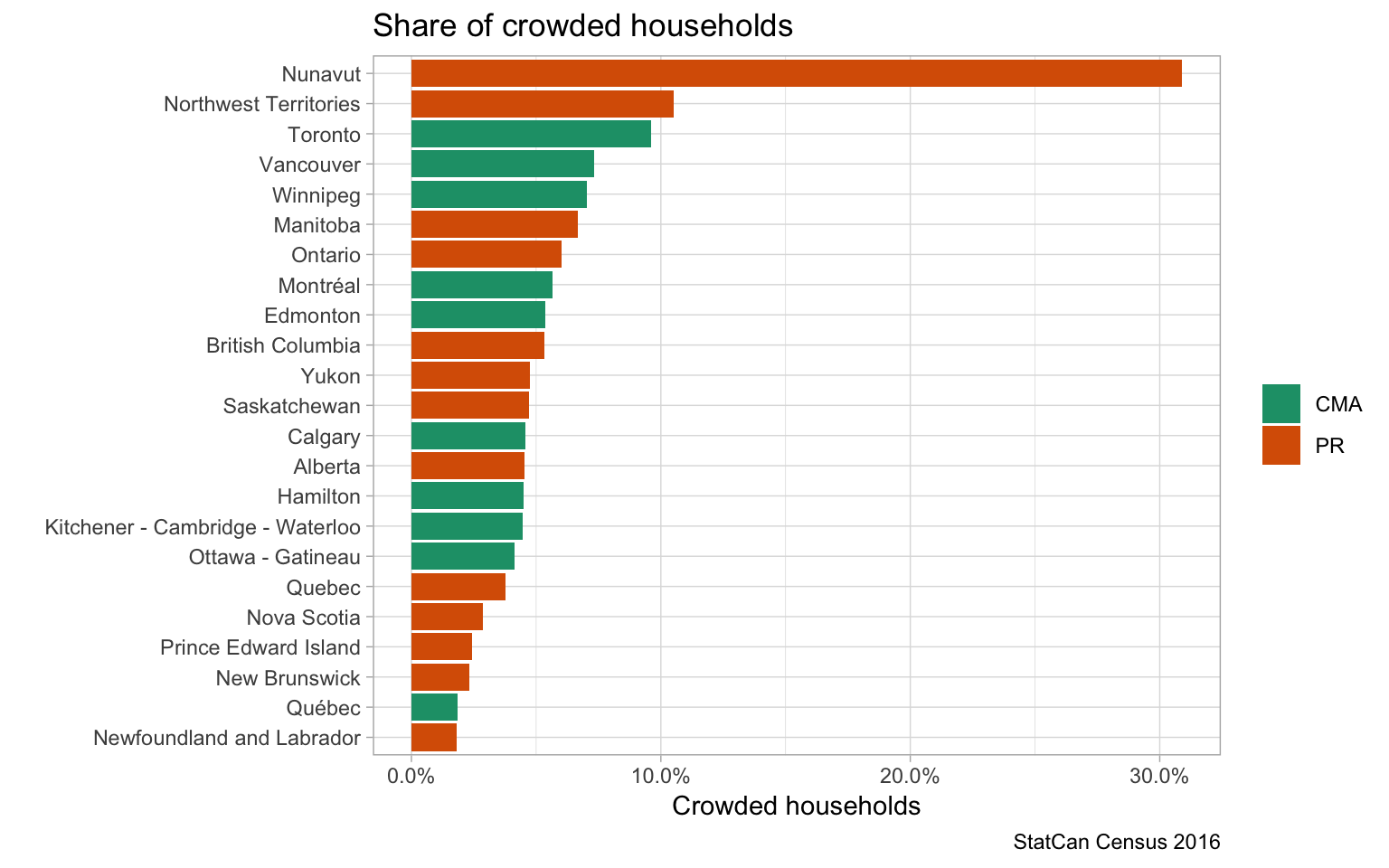

Across most of Canada residential crowding remains low. This is especially true of those places with strong municipal regulations against crowding (e.g. fire codes and occupancy standards) and market distribution of housing. Non-urban, non-market housing, especially on First Nations reserves and in Nunavut, where rationing is more common, tends to be where we see the greatest number of people per dwelling. Here we see a real failure of investment in non-market housing to match occupancy standards observed elsewhere, though differences in family sizes and cultural openness to different rules for living together also play a role.

While crude aggregate crowding metrics can help reveal the lack of housing across reservations and Northern territories, they don’t tell us much about differences between metropolitan areas, which stick together in a relatively narrow range between two to three people per dwelling. The narrow range reflects how crowding is both generally outlawed and also discouraged by market mechanisms distributing the vast majority of housing (above). We also know residential crowding is on the decline in most places, resulting from long-term declines in childbearing, family size, and tolerance for living together combined with the general rise of affluence, occupancy standards and enforcement. Correspondingly, crude aggregate crowding metrics should probably not be used to answer questions about whether metros or municipalities have enough housing. They don’t tell us much.

Despite their problematic nature, people per dwelling metrics are commonly used to answer questions for which they’re not suited. Several municipal planners and even a couple of academics have used new persons (or new households) per new dwelling as a metric for whether a place is adding enough housing. Given constraints on crowding and market mechanisms, this is equivalent to asking whether housing supply is meeting demand (as above). Of course it is! By definition, local housing is ALWAYS meeting demand (at some price). Similarly, by definition if you count all of the housed people added and all of the new housing added in a given location, there will always appear to be enough housing added to house everyone (at some level of crowding). After all, only housed people are counted, meaning only the net “winners” able to out-compete others for the dwellings being offered by the market. Net “losers” not provided housing by the market don’t get counted at all! Put differently, if price metrics weigh the whims of the wealthy too high relative to the needs of the poor (a valid critique), then crowding metrics ignore everyone without local housing entirely: all the people who want to live in a place but are prevented from finding housing there don’t get a vote.

Despite their problematic nature, people per dwelling metrics are commonly used to answer questions for which they’re not suited. Several municipal planners and even a couple of academics have used new persons (or new households) per new dwelling as a metric for whether a place is adding enough housing. Given constraints on crowding and market mechanisms, this is equivalent to asking whether housing supply is meeting demand (as above). Of course it is! By definition, local housing is ALWAYS meeting demand (at some price). Similarly, by definition if you count all of the housed people added and all of the new housing added in a given location, there will always appear to be enough housing added to house everyone (at some level of crowding). After all, only housed people are counted, meaning only the net “winners” able to out-compete others for the dwellings being offered by the market. Net “losers” not provided housing by the market don’t get counted at all! Put differently, if price metrics weigh the whims of the wealthy too high relative to the needs of the poor (a valid critique), then crowding metrics ignore everyone without local housing entirely: all the people who want to live in a place but are prevented from finding housing there don’t get a vote.

Contributing to this fundamental problem, net housing additions are also often poorly counted, either because of changing census methods or failure to combine completions data with demolitions data. This has proven a particular problem for analyses that take for granted how people distribute themselves into households and simply compare new households to new dwellings, taking the leftover number of new dwellings as “empty” excess (in this case, the number of net new housed households can never exceed the number of net new dwellings except in cases where there were previous “empty” dwellings). Given the myriad of problems involved, crude aggregate measures of new persons or new household per new dwelling are especially poor metrics for determining if metro areas or municipalities are building enough. The answer they provide, by default, is practically always “yes.” For similar reasons, reinterpreting past census counts into population projections as the basis for how much housing development to allow is backwards. In high demand places, the availability of housing limits population growth rather than the other way around. Planners and academics should stop using metrics that count only local winners as answers to whether we’re building enough housing.

What about more refined measurements of crowding at different levels of analysis? These are often worthwhile to consider. Given a few strong assumptions about the privacy needs of people while they sleep (practically the least interesting activity they undertake), residential crowding can be measured in terms of bedrooms rather than simply dwellings. Measured at the household level, we can get a sense of how many households are living in dwellings that force more than two people to share a bedroom. We can come up with even more elaborate rules, as in the Canadian National Occupancy Standard, where we assume people need one bedroom per sleeper, but we allow couples to share with each other, and kids to share with other kids (below age 6) and other kids of the same gender (below age 18). Applying these rules more clearly demonstrates the residential crowding on First Nations and in Nunavut. But once again, the metric tells us little about most municipal and metropolitan variation.

We can also refine measures to explore residential sharing at particular ages. When do children leave home? It might be that adult children remaining living with their parents is a sign of need for more dwellings. This is tenuous as an indicator (some children want to stay home, others do not), but interesting!

We can also count individuals without dwellings. This is a form of mismatch. Given the current distribution of housing, how many people are going without? Homeless counts offer an important signal about whether there’s enough housing: if we can count people who are homeless, then there is not enough housing. But this is a broader problem with inequality. Bringing more housing to market may not solve the problem, especially since the demand for housing isn’t just local, and the whims of the wealthy will continue to outweigh the needs of the homeless. Homeless counts are an especially good signal of the need for more non-market housing. Of course, another good signal of the need for non-market housing are the waitlists for cooperative, subsidized and supportive housing. Effectively, both homeless counts and non-market housing waitlists register urgent local needs not being met by the market distribution of housing. That said, homeless counts and waitlists suffer some of the same problems as other crowding metrics insofar as they only tend to record housing need that’s already in a given locale. But people fall in and out of need and they also move. The dire needs of refugees in tent camps tens or thousands of miles away do not get considered, even if those refugees might eventually show up in a municipality. As a result, there remain difficulties in determining just how much need to meet: there are probably no ethically satisfactory stopping points. And even if there were, under rationing systems of all sorts, housing waitlists can grow to enormous lengths. As with attempts to preserve market affordability, we can know we need to build a lot more non-market housing without necessarily knowing when (or if) we should stop.

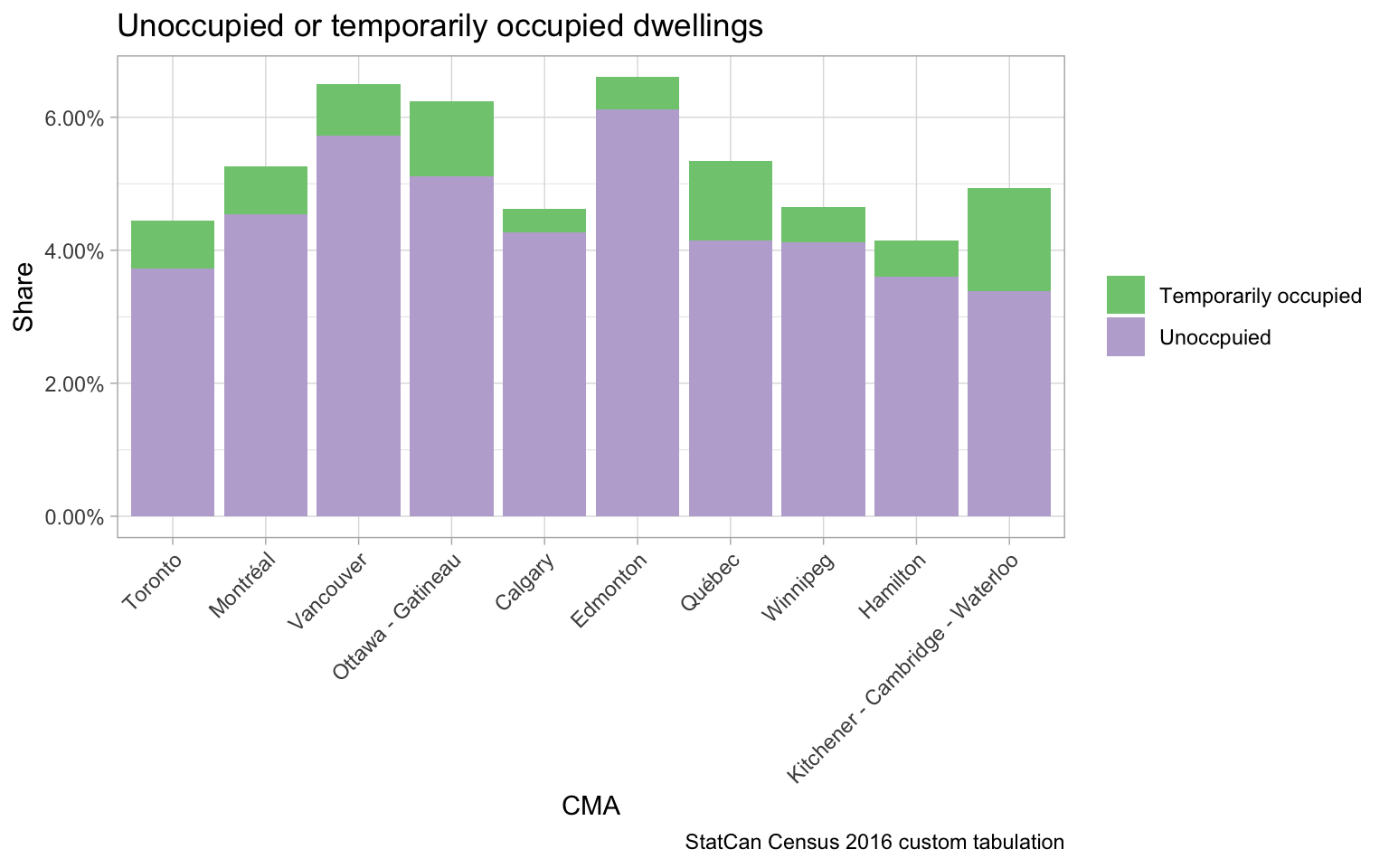

Finally, returning to the notion of “excess” dwellings, we can also count dwellings without people in them. This is ultimately a bad measure of whether there’s enough housing without a) greater knowledge of the reasons why units appear to be empty and without b) a corresponding will to expropriate “bad” empty units and ration them out according to need. Speaking to the first point, if dwellings register as “vacant” and available to the market (e.g. rental vacancies or unoccupied sales listings), then these dwellings will help reduce prices (see above). If they’re not on the market, they may reflect development processes (pre-demolition or recently constructed dwellings) working toward adding more housing. A variety of other procedural transitions (deaths, inheritances, etc.) may also account for dwellings without people in them before we get to second “vacation” residences (whims of the wealthy, etc.), and alternative uses (AirBnBs, etc.). To the extent these kinds of unoccupied dwellings are rising, they may result in reductions to the market supply of housing, pushing up prices for dwellings that remain. Finally, keeping housing empty and off the market may result from attempts to reduce transaction costs and/or speculatively manipulate market pricing. This is of greatest concern from the standpoint of maintaining market stability and affordability. The diversity of reasons that dwellings might show up as unoccupied means that, by itself, keeping track of unoccupied or empty dwellings is probably a bad measure of whether the market is building enough housing. After all, empty units may be adding to supply or detracting from supply, with varying affects on affordability, depending upon whether they’re on the market. That said, like homeless counts, “empty home” counts can be useful as an indicator of how the market is working to match people to dwellings (given underlying and unmeasured inequality). Moreover, empty homes can be bad in their own right, potentially deadening neighbourhoods. A Lincoln Institute report defines thresholds at which vacancy becomes a problem, with “low” vacancy (a problem for facilitating moves) below 4%, “reasonable” vacancy between 4%-8%, and high vacancies at 8%-20%. “Hypervacancy” (20% or more) poses special problems, especially in the case of declining cities. All major Canadian metro areas fit in the “reasonable range.”

But in high demand cities, lots of empty homes can point toward the desirability of higher property taxes, potentially including Empty Homes Taxes, which can distinguish between types of vacancies and induce owners of empty units and second homes to more quickly return them to market, boosting supply and lowering prices. This will reduce the profitability of any speculative market manipulation. But of course another response to that kind of manipulation is to add more dwellings and credibly promise to keep adding dwellings, placing pressure on prices and rents to lower over time and make speculation unprofitable.

Dwellings per Land (a.k.a. dwelling density)

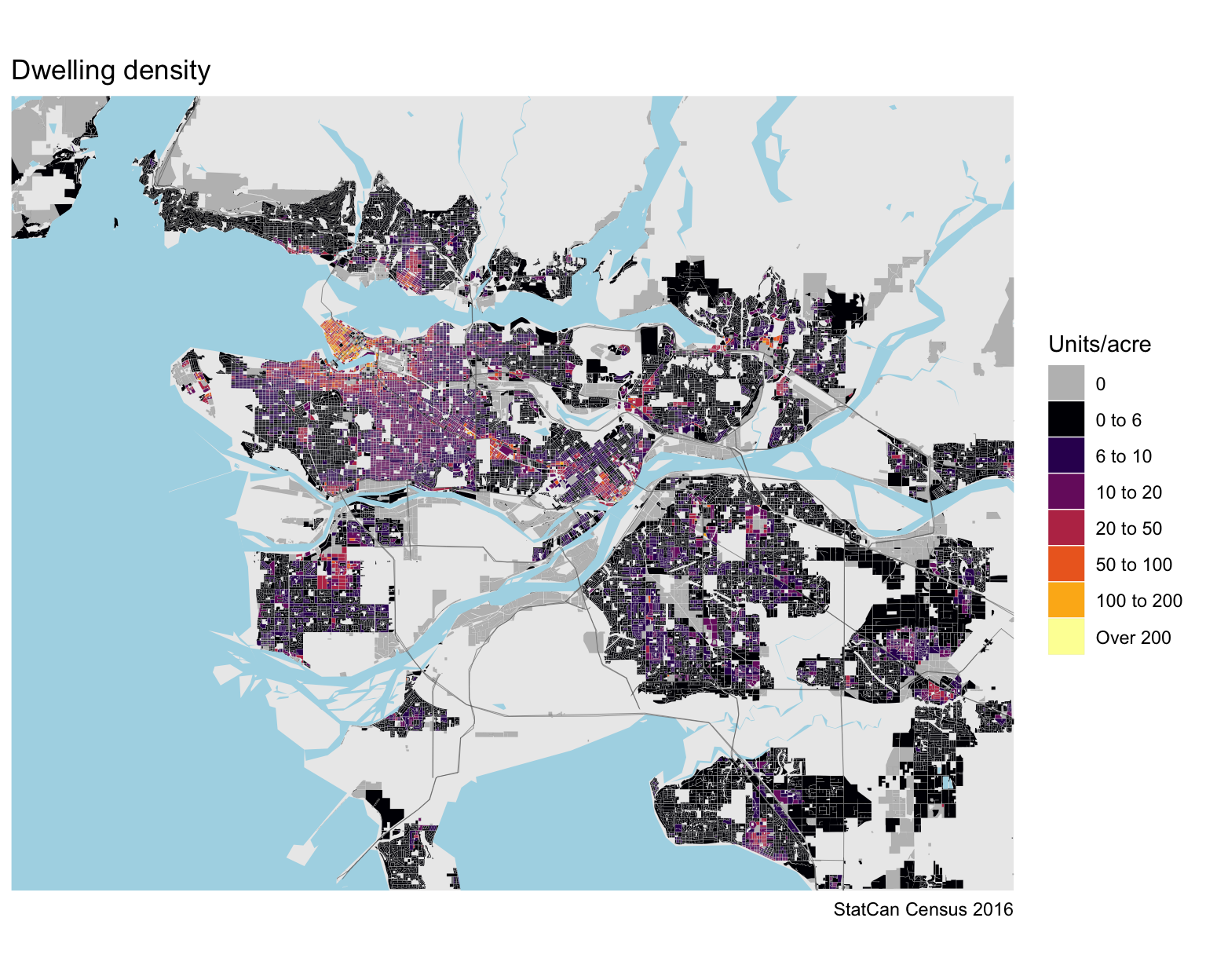

Dwellings per unit of land as a class of metrics measures dwelling density, constituting yet a different aspect of whether there’s enough (or too much) housing in a given place. This class of metrics has important implications for urban dynamism and environmental impact. It also has potential effects on for parking, noise, and the preferred aesthetics of many neighbourhood organizers. Dwellings per unit of land is often measured as dwellings per acre or hectare. Beyond definitional issues, there are tricky aspects to measuring this, insofar as both the areal unit (lot, block, neighbourhood, municipality, metro area) and what gets counted as potential land for dwellings (in the denominator) really matters. If we’re interested in housing density, should one count only land allowing dwellings? What about streets? Or other land uses, like industrial parks? What about recreational parks? Schools? Subtracting out streetscapes makes a big difference, and when other features fall within small areal units, like blocks, they can really affect measures of housing density, making a block with a park look much less than dense than the block next door, even if both are made up of entirely the same kind of housing. Counting only land allowing dwellings constitutes “net housing density” while counting all land and uses constitutes “gross housing density.”

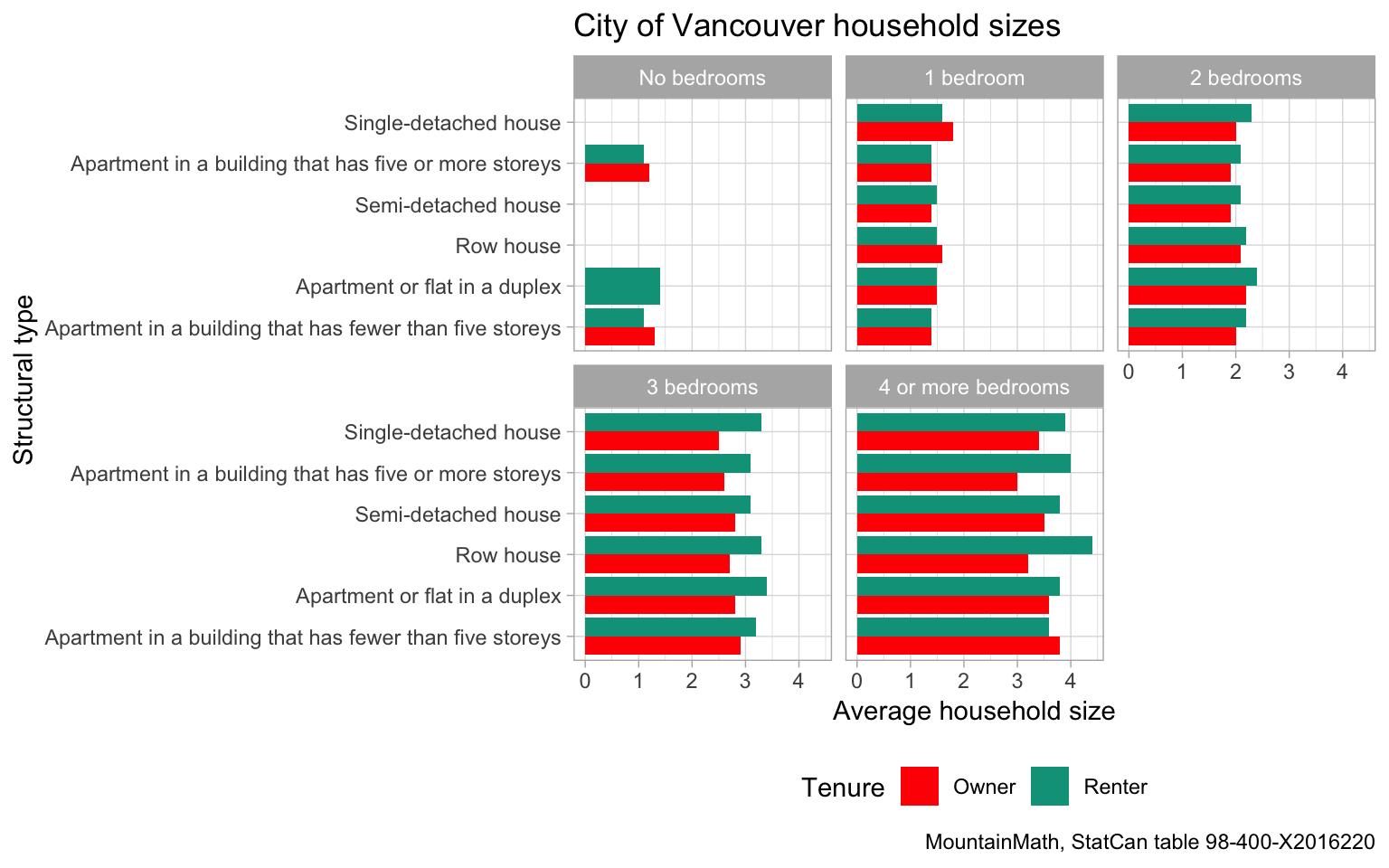

Overall it’s worth noting that this class of metrics is also a bit of a dodge, since often what we’re really interested is people per unit of land, better known as population density. After all more people in a given place constitute more potential interactants in public spaces, more likely transit riders, more shares of infrastructure, and more possible “eyes on the street.” More people also constitute more potential competition for parking and services. People sharing space are also often understood to be poor and potentially dangerous, bringing down property values. So debates over housing density as a class of metrics are often really about how many people should be encouraged or tolerated in a given place. But the regulatory powers of cities are stronger over buildings than bodies, so the focus often ends up being on dwelling density rather than population density. Aside from population density, dwellings per unit of land can have independent effects on the aesthetic “character” of neighbourhoods, as expressed by many peoples’ aversions to high-rises. As noted above, we can, more or less, substitute between population density and housing density just by dividing population density by average household size. This doesn’t always work, insofar as denser housing tends to hold smaller households, but it still gives us a rough translation. We can even figure in unoccupied dwellings if we want, which would give us an overall standard of about 2.34 people per dwelling in Metro Vancover. Alternatively, instead of measuring dwellings per acre, we could measure bedrooms per acre. Bedrooms relate more closely to population than dwellings, and are often similarly regulated by cities.

In terms of impact, housing density (or dwellings per acre) has been linked to urban vitality. Jane Jacobs famously set a few thresholds for what she considered suburban (six or fewer dwellings per acre) and truly urban (one hundred or more dwellings per acre). She considered “in-between densities” as less conducive to the “lively diversity and public life” of the city. Needless to say, the vast majority of the landscape of North American cities fall in Jacobs’ “in-between” ranges, “fit, generally, for nothing but trouble.” Outside of Downtown and a few other scattered census tracts, the same is also true of Metro Vancouver. Where the best threshold for urban vitality might be located remains a matter for debate.

Similar thresholds have been suggested for what kind of densities can support urban transit. Commonly cited thresholds suggest about 12 dwellings per acre around a large central business district is enough to support a decent urban transit system. Guerra & Cervero provide more careful updates on this estimate, exploring capital costs in conjunction with what can be supported by population and jobs located near stations. Using their estimates, a project like Vancouver’s forthcoming skytrain extension along Broadway, at a capital cost of nearly $500/km2 CAD (nearly $600/sq mile USD), would require over 120 people per acre gross population density to support, or more than 50 dwellings per acre near skytrain stations.

Generally speaking, higher dwelling densities enable more transit viability, encourage people to get out of their cars (when coupled with jobs and commercial destinations), promote lower energy useage and generally support transitions to more sustainable cities. But higher dwelling densities also challenge some peoples’ conceptions of what they want their neighbourhoods to look like and how many people they want to compete with for parking. Moreover, higher dwelling densities tend to be forbidden on the vast majority of North America’s urban land base. Why? Zoning.

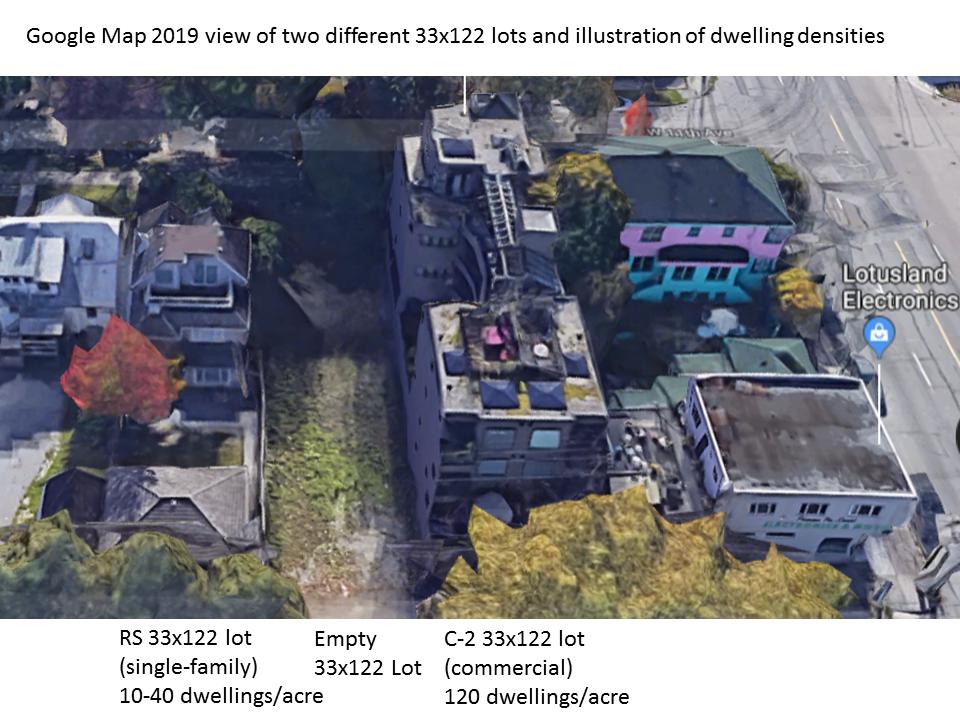

Most residential land, including in the City of Vancouver and surrounding suburbs, is zoned to support single-family residential character. At its strictest, single-family zoning insures only one dwelling can be built per lot, and in some cases minimum lot sizes can be enormous. Dwellings are often rationed out according to quite draconian land use rules. Even on the relatively modest 33’ x 122’ standard residential lots that make up a large part of Vancouver’s urban landscape, a single dwelling per lot standard nets only about 10 dwellings per residential acre. Initiatives to add and legalize secondary suites, laneway houses, and most recently duplexes (with secondary suites) means that the actual range of legal dwellings per lot on most single-family zoned land in the City of Vancouver can get all the way up to 40 dwellings per acre. Not bad, but nowhere near the densities supportive of urban vitality or skytrains.

On the other hand, a 33’ x 122’ lot located within a commercial zone in Vancouver is allowed greater dwelling density and the ability to build out to lot lines. Even under the same broad height restrictions applied to single-family zoning, twelve dwellings can easily be fit into a given lot while retaining a central courtyard, achieving a dwelling density of about 120 dwellings per residential acre, like this low-rise apartment building in a C-2 (where one of the co-authors of this post lived when he first moved to Vancouver). This moves solidly into Jane Jacobs & heavy transit supportive territory, though the difference between net density and gross density suggests we’re still not quite there yet.

On the other hand, a 33’ x 122’ lot located within a commercial zone in Vancouver is allowed greater dwelling density and the ability to build out to lot lines. Even under the same broad height restrictions applied to single-family zoning, twelve dwellings can easily be fit into a given lot while retaining a central courtyard, achieving a dwelling density of about 120 dwellings per residential acre, like this low-rise apartment building in a C-2 (where one of the co-authors of this post lived when he first moved to Vancouver). This moves solidly into Jane Jacobs & heavy transit supportive territory, though the difference between net density and gross density suggests we’re still not quite there yet.

Setting Rules to Metrics

A lot of the metrics we describe above are set into rules (e.g. by-laws, policies, etc.) for regulating cities. In particular: zoning by-laws often set hard limits to dwelling density (dwellings per land) and maximum square footage (Floor Space Ratios) for given lots. The metrics embedded in our zoning effectively mean that we’re rationing out how many dwellings we allow per land parcel. Through the sharing rules embedded in our occupancy standards, we’re also disallowing most residential crowding. But after we apply these rationing and sharing rules to structure housing production and occupancy, we switch to the market in terms of how we develop and distribute most housing. In high demand locations, the net result of these general policies is construction for rich people and the gradual exclusion of poor people. Their dire needs in the market weigh as less important than the whims of the wealthy. Since poor people are also prevented from sharing existing dwellings in high concentrations, they can’t even get a foot in the door, and don’t show up in crowding metrics at all.

While some rules set to metrics are built to be responsive and flexible, automatically adjusting to conditions (e.g. setting rent control to inflation, and setting below-market rates at a set discount from market rates), others require lengthy hearings and political debates to change (changing zoning). As presently configured, debates about dwelling density largely exclude everyone not currently living in our cities. Indeed, this is one reason legislators in places like California and Oregon have moved to erode the power of municipalities to exclude development near transit hubs. They want to give potential renters and buyers a bigger say in whether we have enough housing by allowing them to speak through the demand curve, encouraging developers to build more housing in these places. To date the political process hasn’t let them get away with much, which ironically insures that developers profit hansomely from the scarcity of new housing being added to the market. In a high demand place like Vancouver, this means that in the long term, rents and prices tend to just keep going higher (though as we’re learning, in the short term prices can still swing up and down in line with speculative booms and busts, just like anywhere else!)

If we’re concerned about the exclusionary effects of high prices, we could reform our zoning regulations to be responsive, automatically adjusting to both transit development and market conditions (just like with rent control or the setting of below-market rents). There seems to be a lot of potential in considering this possibility. One example would be to set affordability thresholds. We could, for instance, automatically enable a rise in the number of dwellings permitted on a lot equal to one for every $250,000 in its assessed value. Once a lot hits three million in value, we could automatically enable up to twelve dwellings, looking something like the building above. Thresholds for non-market housing could be set even lower, enabling non-market developers (including the City) a competitive advantage in securing lots. Cities could also take over the production of non-market dwellings themselves, purchasing low-density lots and using their power over zoning to upzone and redevelop for the higher densities needed to support a more economically diverse population.

Conclusion (and Preview)

Overall, there’s still lots to think through when asking if we have enough housing! But metrics can establish crucial common ground for providing answers. Stripping down our metrics to their basics helps demonstrate their utility in terms of what answers they can provide and who they give voice. Overall, price (and rent) metrics provide the best indicators of whether we have enough housing to preserve or achieve market affordability. Non-market waitlists and homeless counts provide the best indicators of local non-market housing need (though they still exclude need from elsewhere). By contrast, residential crowding metrics (people per dwelling) don’t generally tell us much in urbanized Canada, and tend to privilege the voices of those already living in a place (e.g. the “winners” in finding housing). Dwelling per land metrics point toward the limits often imposed upon getting to enough housing in a place, and potentially spell out the rewards for getting there in terms of sustainability and urban vitality.

In terms of underlying logics, the market distribution of housing tracked by price metrics is problematic insofar as the whims of the wealthy far outweigh the dire needs of the poor. But when we simply wave away price metrics, and pretend we’re rationing out housing by need instead (by only tracking persons per dwelling), then we’re saying we don’t care who wins for the limited amount of housing we’re willing to offer when we ration out dwellings to land. Really addressing housing need is a monumental and important task, and requires a much greater investment in non-market housing. But questions quickly arise as to how non-market housing should be rationed, and advocates should pay more attention to providing answers that don’t assume that no one ever moves.

In future posts on housing metrics, we’ll compare across specific measurements within the same class and dig further into more complicated metrics that combine multiple classes (e.g. price to income multiples, core housing needs, shelter & transportation cost to income rations, etc.) So consider this a preview. Rest assured we’ll keep playing around with metrics!

Reuse

Citation

@misc{simple-metrics-for-deciding-if-you-have-enough-housing.2019,

author = {Lauster, Nathan and {von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Simple {Metrics} for {Deciding} If {You} {Have} {Enough}

{Housing}},

date = {2019-06-12},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-06-12-simple-metrics-for-deciding-if-you-have-enough-housing/},

langid = {en}

}