A number I have been watching fairly closely is the job vacancy rate. It comes from StatCan’s Job Vacancy and Wage Survey (JVWS), and is updated quarterly. It is one of several surveys that complement the Labour Force Survey (LFS) that tends to receive a lot of attention. But the LFS is missing some important aspects of the labour market. I have been pushing JVWS data on numerous occasions, so I wanted to do a quick post to add a little more context. This is also a good opportunity to mix in data from the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH) and the Canadian Income Survey (CIS).

The LFS reports employment (and unemployment) numbers. Often this is used as a stand-in for the number of jobs, but the LFS is an imperfect proxy for two reasons.

- The LFS is based on geography of residence of the workers, not on the geography of where their job is. This matters when looking at timelines at the CMA level, where for example in Vancouver the number of workers commuting (net) in from Abbotsford-Mission CMA has increased over time. The LFS misses this trend and, when used as a proxy for jobs, will under-estimate job growth in Metro Vancouver and over-estimate job growth in Abbotsford-Mission.

- The LFS does not capture job vacancies, that is jobs that are currently vacant and actively looking to get filled. Thus the LFS misses job growth beyond what the current labour market is able to fill, although it reports on proxies like low unemployment rate and high participation rate that usually come alongside elevated job vacancy rates.

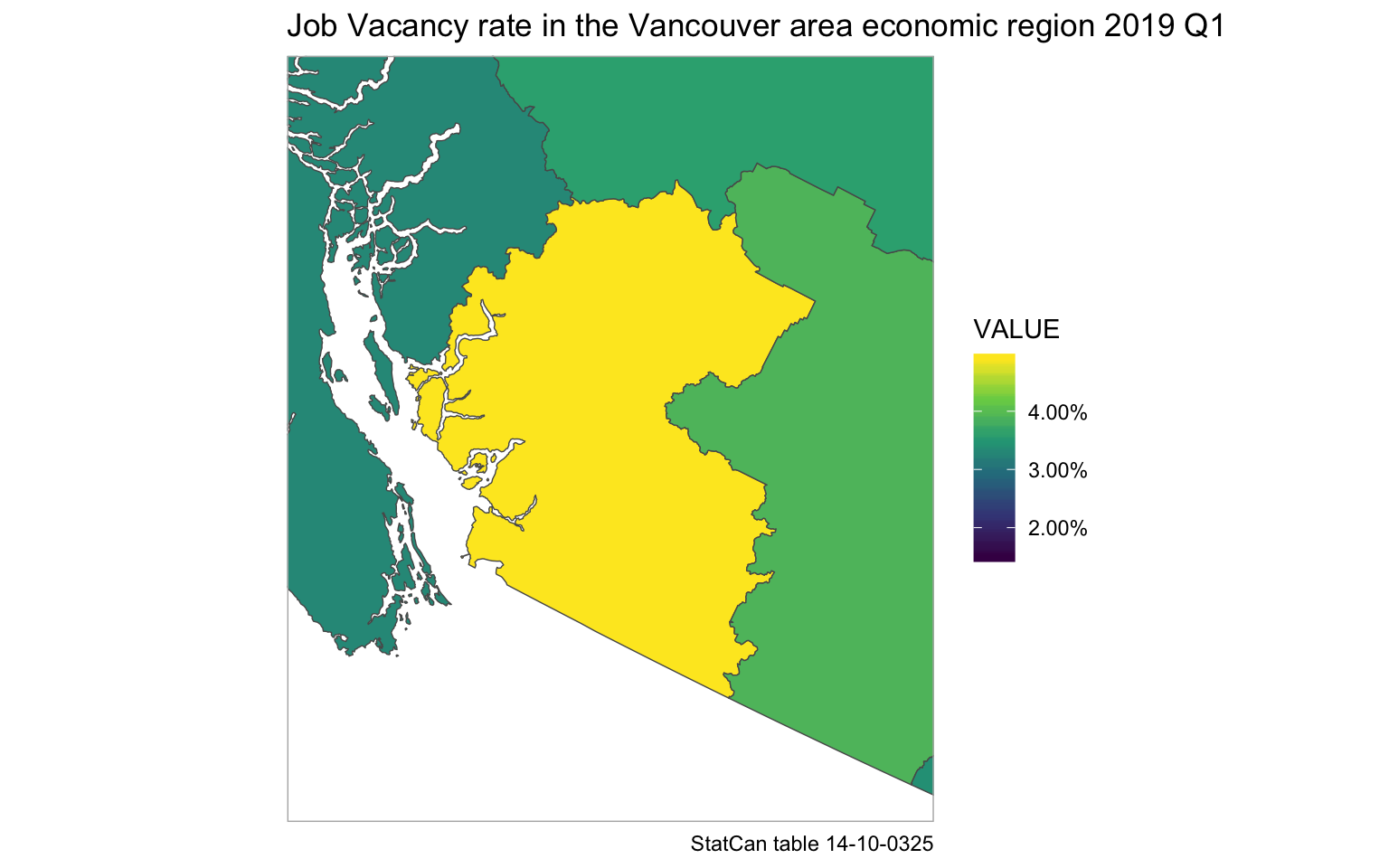

Unfortunately the JVWS is not available at the CMA level, only at economic regions. For Vancouver that means the economic region of the Lower Mainland-Southwest, which spans the census districts of Greater Vancouver, Fraser Valley and Squamish-Lillooet, and contains Metro Vancouver. The economic region for Toronto consists of Toronto, Peel, York and Durham which misses part of Metro Toronto and contains some parts outside of Metro Toronto.

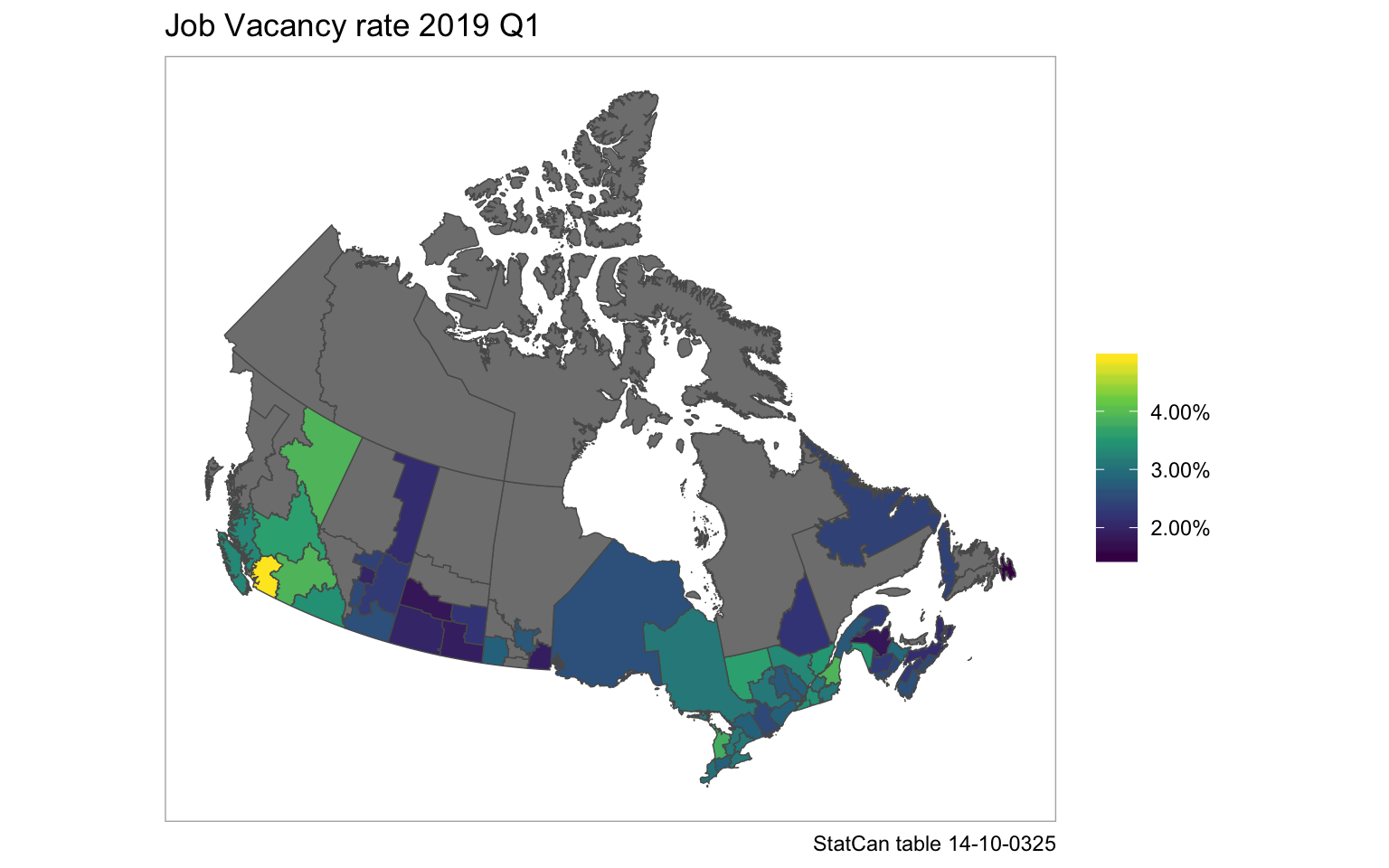

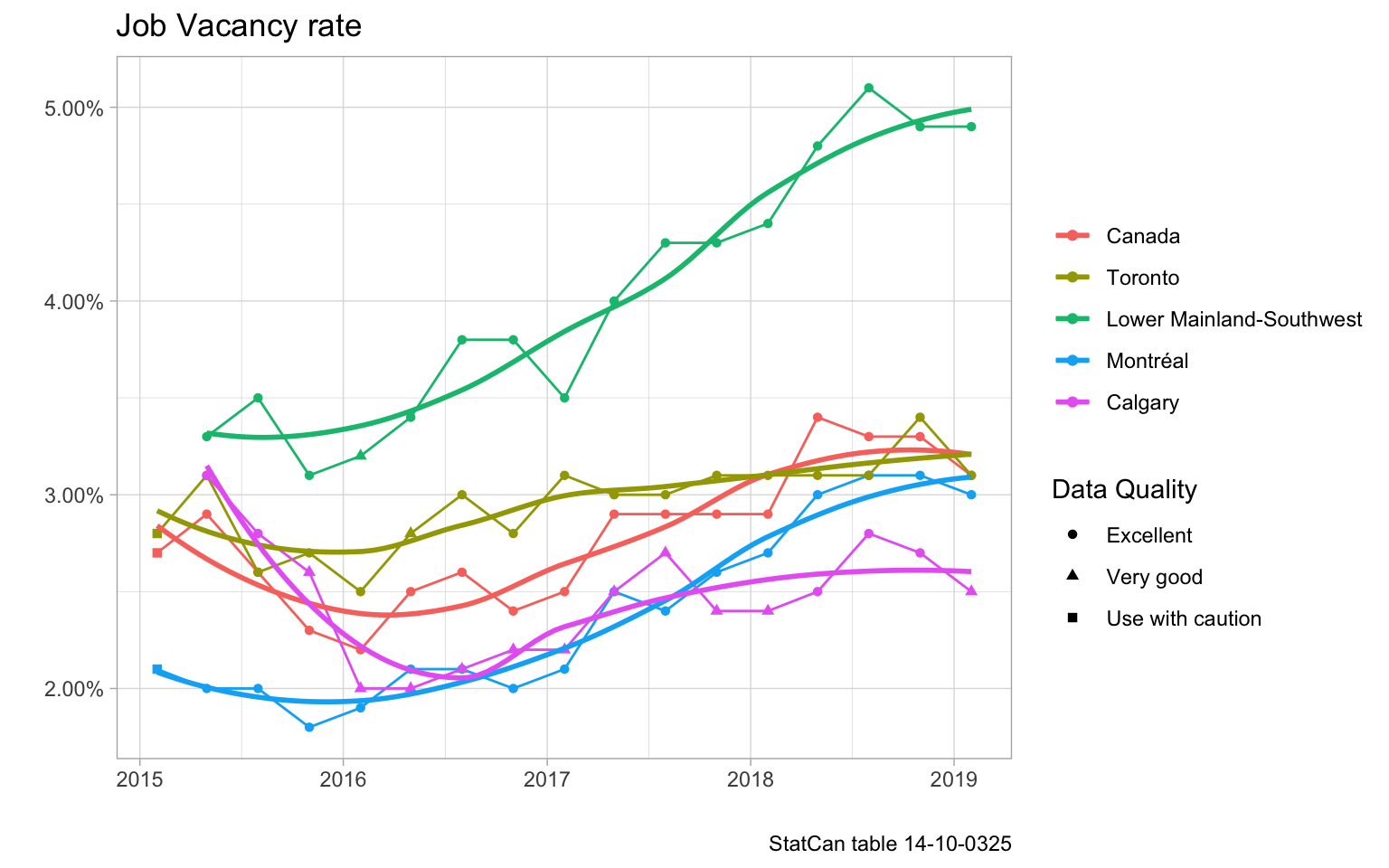

The rate in the Lower Mainland-Southwest with a job vacancy rate of 4.90% immediately jumps out, it’s the only economic region with a job vacancy rate above 4%. We zoom into the area for geographic reference of the extent of the economic region.

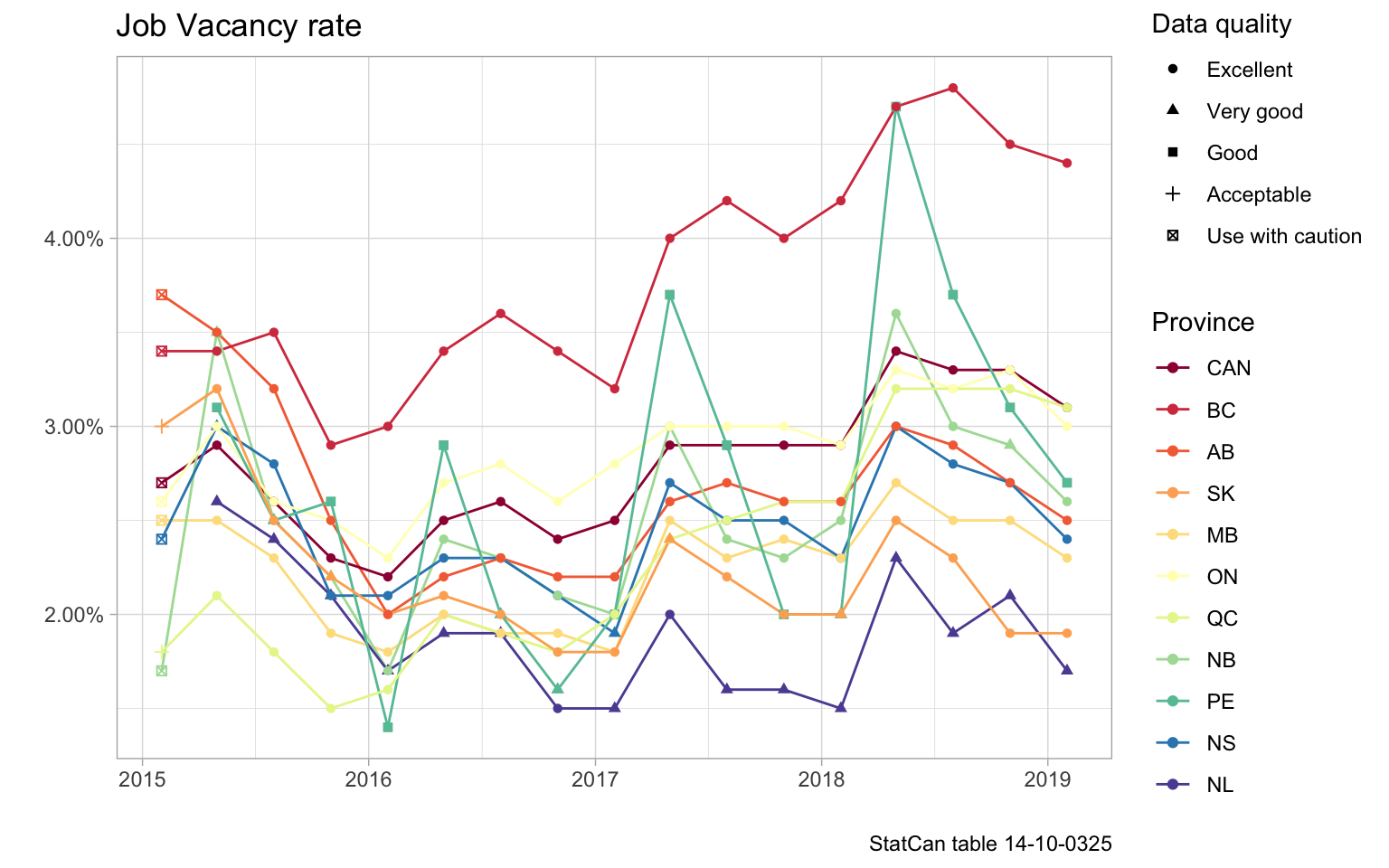

To get a better understanding of the job vacancies, we take a look at the timelines at the provincial level.

There is a fair amount of seasonal volatility in the data, especially for Prince Edward Island and the other maritime provinces. The sharp diversion of BC from the rest of Canada is very obvious, with the rest of Canada in the 1.5% to 3% band while B.C. showed increasing rates that are now far above that of any other province.

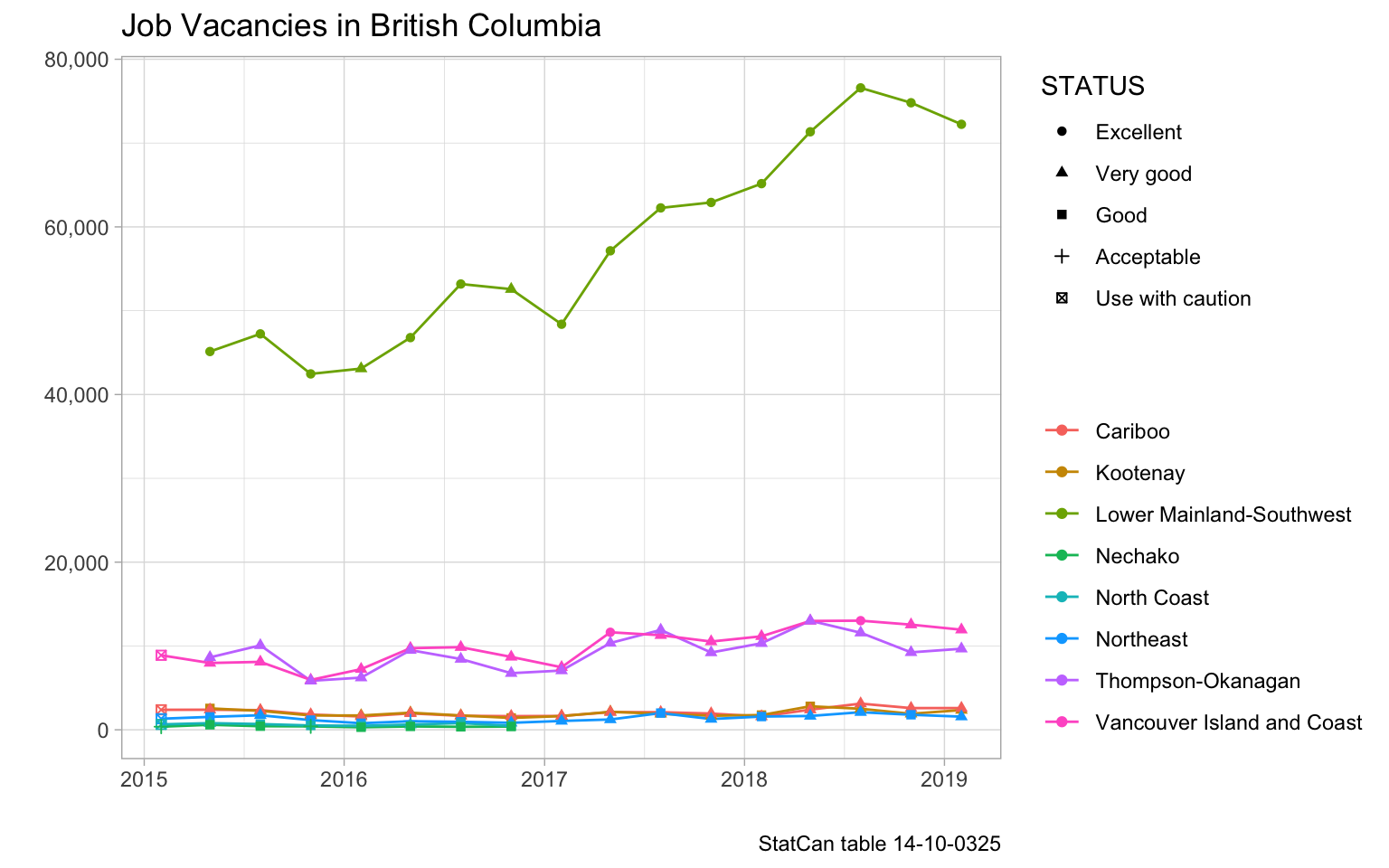

The vacancies in British Columbia are driven by the Vancouver area, so economic region Lower Mainland-Southwest.

Looking at the top 4 economic regions and Canada overall drives home the point how extraordinary the job vacancy rate in the Vancouver area is.

This rise in job vacancy over a fairly short period of time is testament of the growth of the BC economy, and it complements a parallel trend in LFS data.

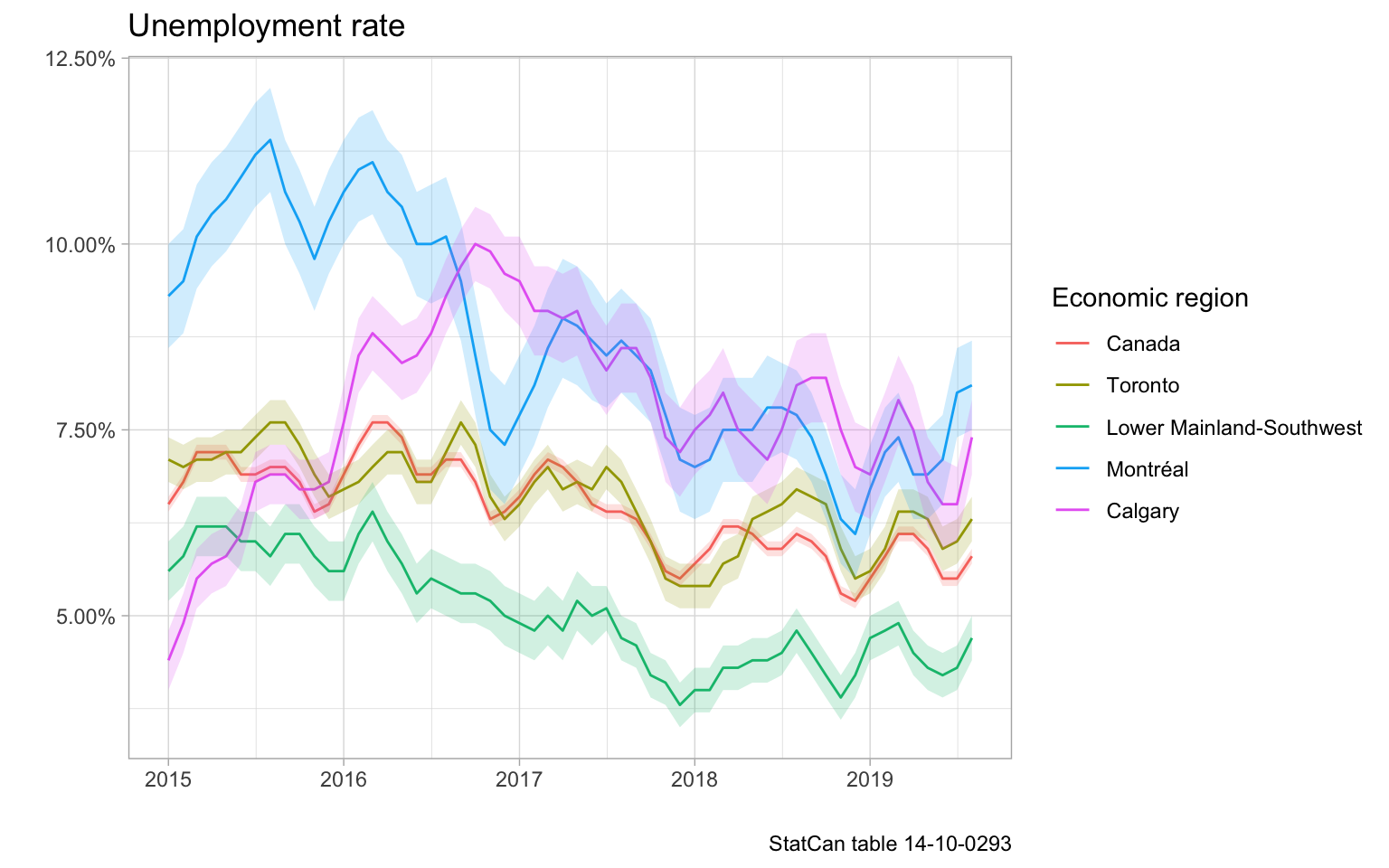

We see that the Vancouver economic region of Lower Mainland-Southwest has the lowest unemployment rate. On the other hand, the economic downturn in Calgary and slow recovery is also clearly visible, where we focus on the same timeframe that JVWS data is available.

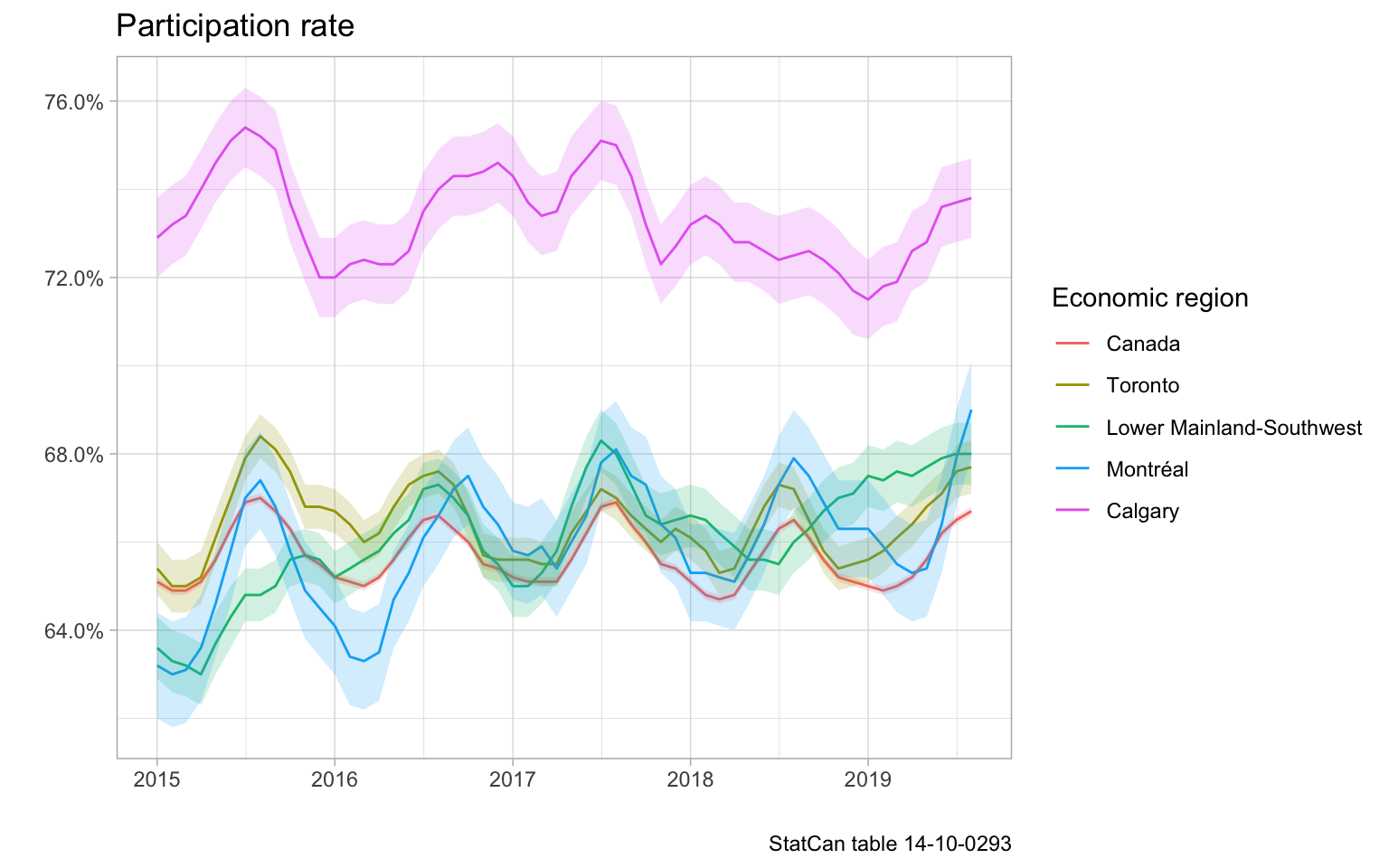

Looking at participation rates, Calgary still stands out with participation rates significantly above the Canadian average. The other economic regions are tracking quite closely, with the Vancouver region gaining ground.

Incomes and wages

This begs the question on the impact on incomes of the employed population, as well as the wages offered for the vacant jobs.

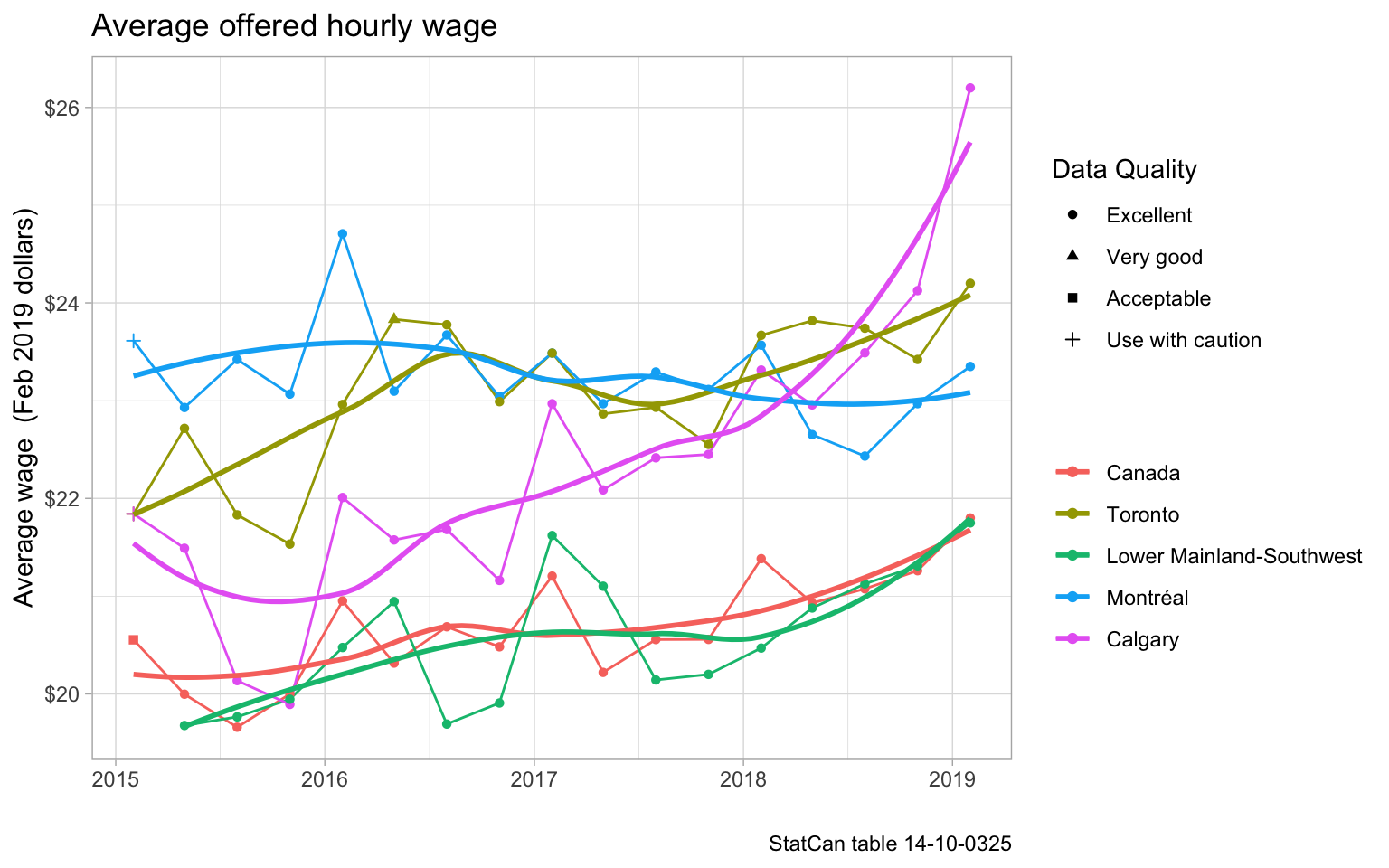

To kick things off we consider the average hourly wage offered for vacant jobs.

The (real) average wage has increased in all areas except Montréal, but the increase in Calgary has been much steeper than that in Vancouver, showing that the job vacancy rate is not the main driver of changes in average wages offered. The type of vacant jobs is an obvious candidate to have a large impact on the wages.

Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH) data

Time to fold in Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH) data. Unfortunately that is only available at the provincial level, so it’s not the best match for our previous data that was focused on economic regions. But it should give a rough indication to how vacancies in different sectors contribute to overall vacancies and how they drive the average offered hourly wage. Here we resort to annual data as samples tend to get too thin for reliable finer temporal data. As a note of caution, this data excludes some sectors. More specifically

Industrial aggregate covers all industrial sectors except those primarily involved in agriculture, fishing and trapping, private household services, religious organisations and the military personnel of the defence services, federal, provincial and territorial public administration, as well as unclassified businesses. Unclassified businesses are business for which the industrial classification (North American Industry Classification System [NAICS] 2017 Version 3.0) has yet to be determined.

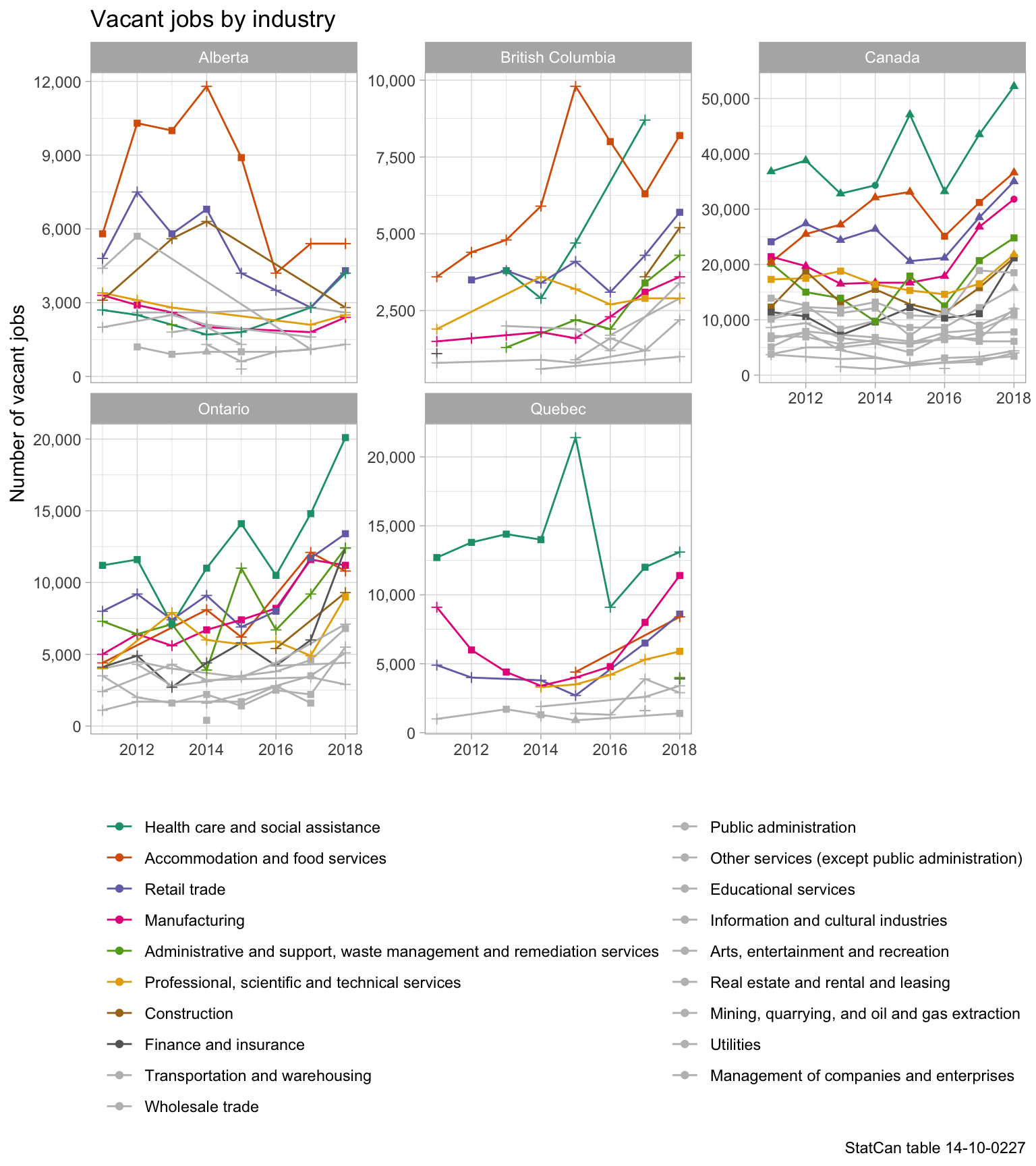

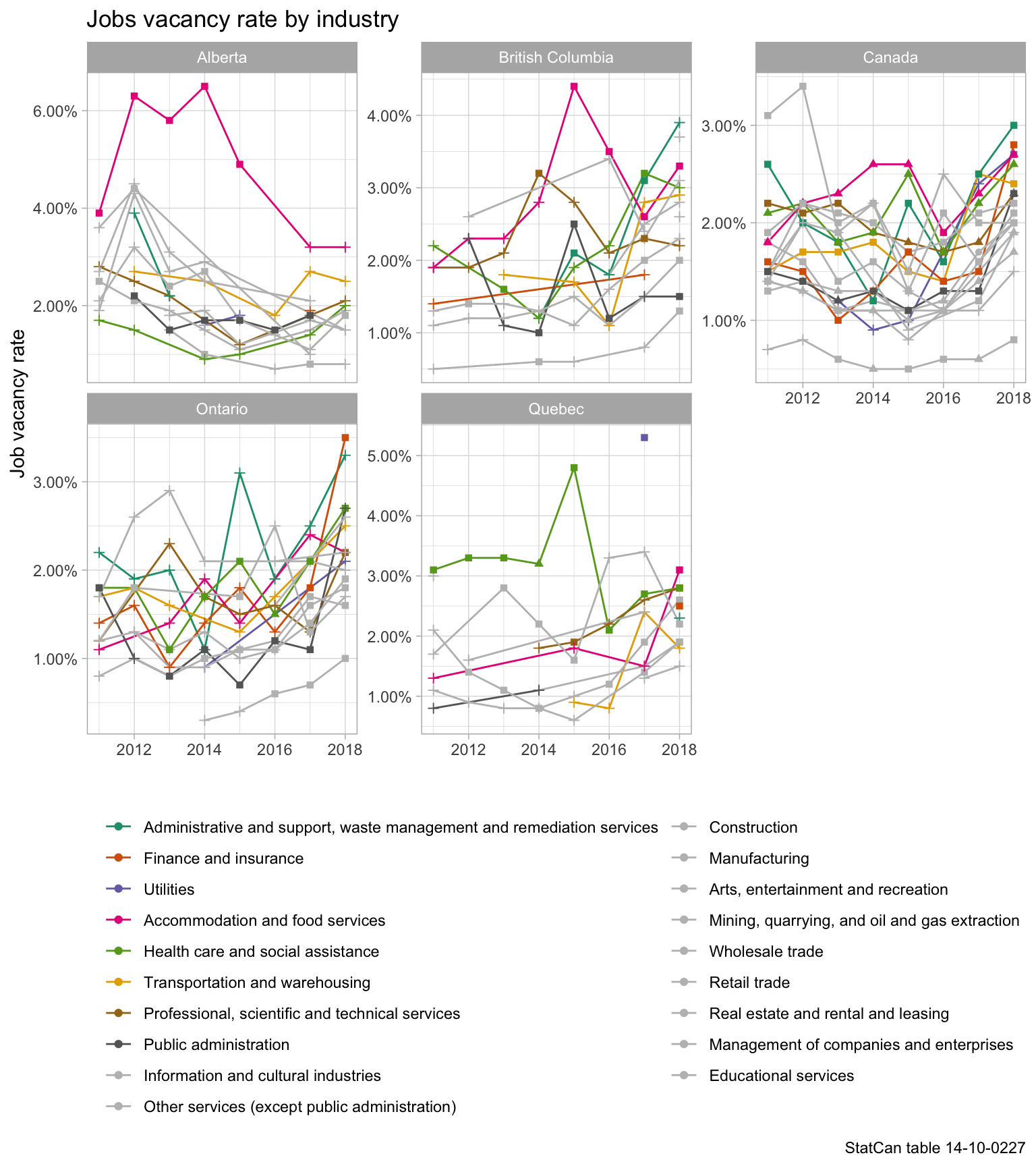

We singled out the 8 most prominent industries to make the graphs more readable. This identifies Health care and social assistance as the main driver of job vacancies Canada wide, while Calgary shows a different pattern with Accommodation and food services winning out. This sector is also featuring prominently in British Columbia. Job vacancy rates by sector add another piece of information.

The data quality suffers when splitting up job vacancies by sector, and it is not clear what impact job vacancies in unclassified businesses have. These patterns don’t seem sufficient to explain the difference in average wages offered for vacant jobs.

Income

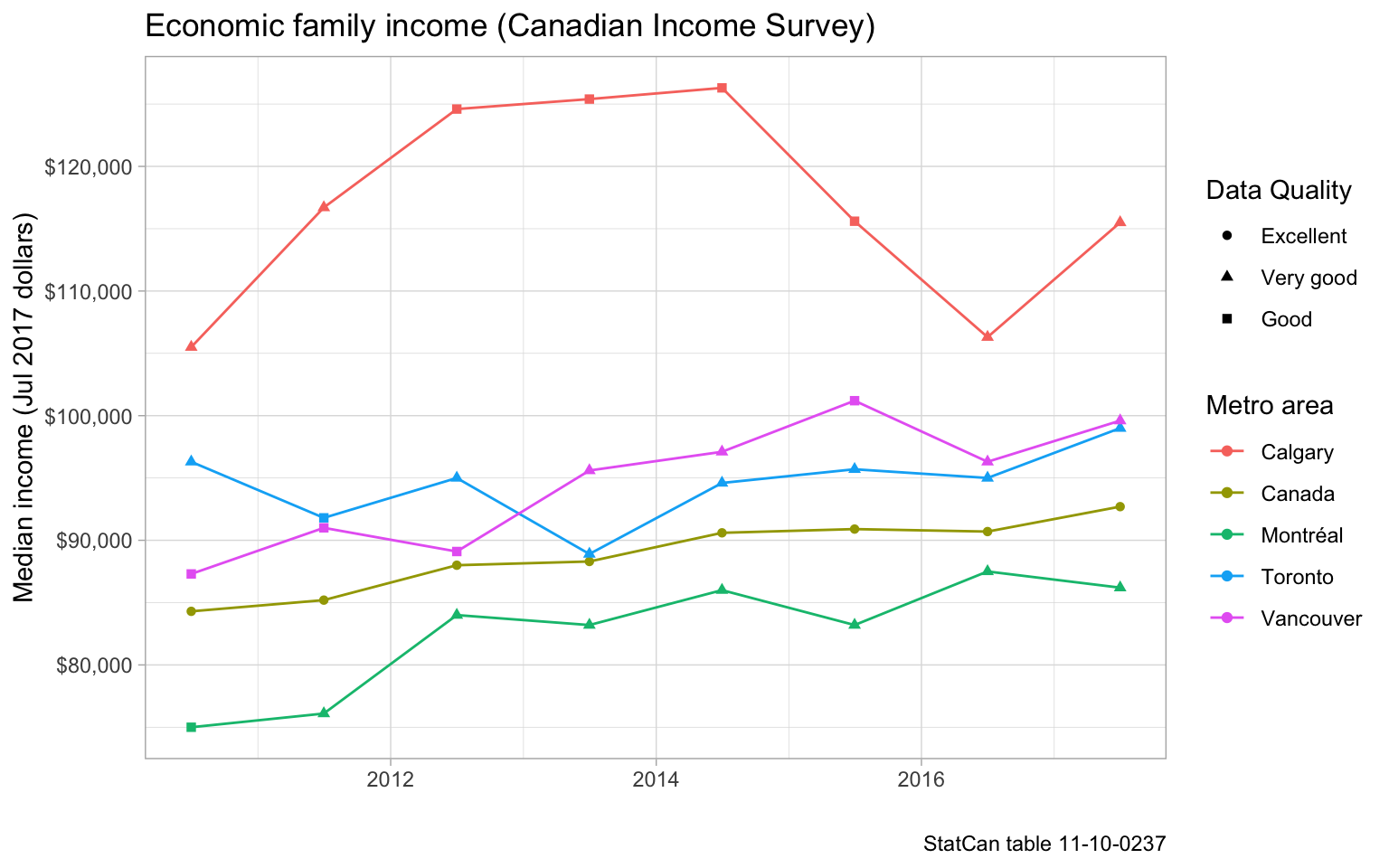

A last clue might come from income of the employed population, complementing the wages offered for the vacant jobs. Here we chose to use Canadian Income Survey data and look at median total income of economic families.

Again, the recent recession in Calgary is clearly visible, but overall income levels remained well above the other metro areas. Vancouver has overtaken Toronto as we have pointed out several times before, with economic families in Toronto posting the lowest real income growth of our metro sample over that time period.

Upshot

There is more to jobs data than just the LFS, and care should be taken not to confuse employment (by place of residence) with jobs. The job vacancy rate plugs one of the gaps between the two, the other is given by cross-boundary commutes.

Metro regions don’t function the same way they initially did. Metro areas can’t be absorbed by other metro areas, so while e.g. Montreal has been growing geographically, Toronto is is quite constrained by water and neighbouring metro areas that show significant cross-boundary commute patterns. The same is true for Metro Vancouver which is bounded by water, mountains, and Abbotsford-Mission to the east.

It’s worthwhile to take a broader look every now and then and see how job vacancies and cross-boundary commutes (available through the census or at lower quality via triangulating various surveys) fit into the picture.

The code for the post is ovailable on GitHub for anyone that wants to explore this further.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{job-vacancies.2019,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Job Vacancies},

date = {2019-09-06},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-09-06-job-vacancies/},

langid = {en}

}