(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

More results from the new Canadian Housing Survey dropped earlier this week! And they provide new insights into why Canadians move.

Last time we only got provincial results. Now we can break down reasons for the last move by metro area and current tenure, but this time around we looking at the last move no matter when it happend, as opposed to only considering moves in the past five years as in the previous data release. So the stats aren’t directly comparable to the numbers from the previous release. But as we’ll show, the trends are pretty similar.

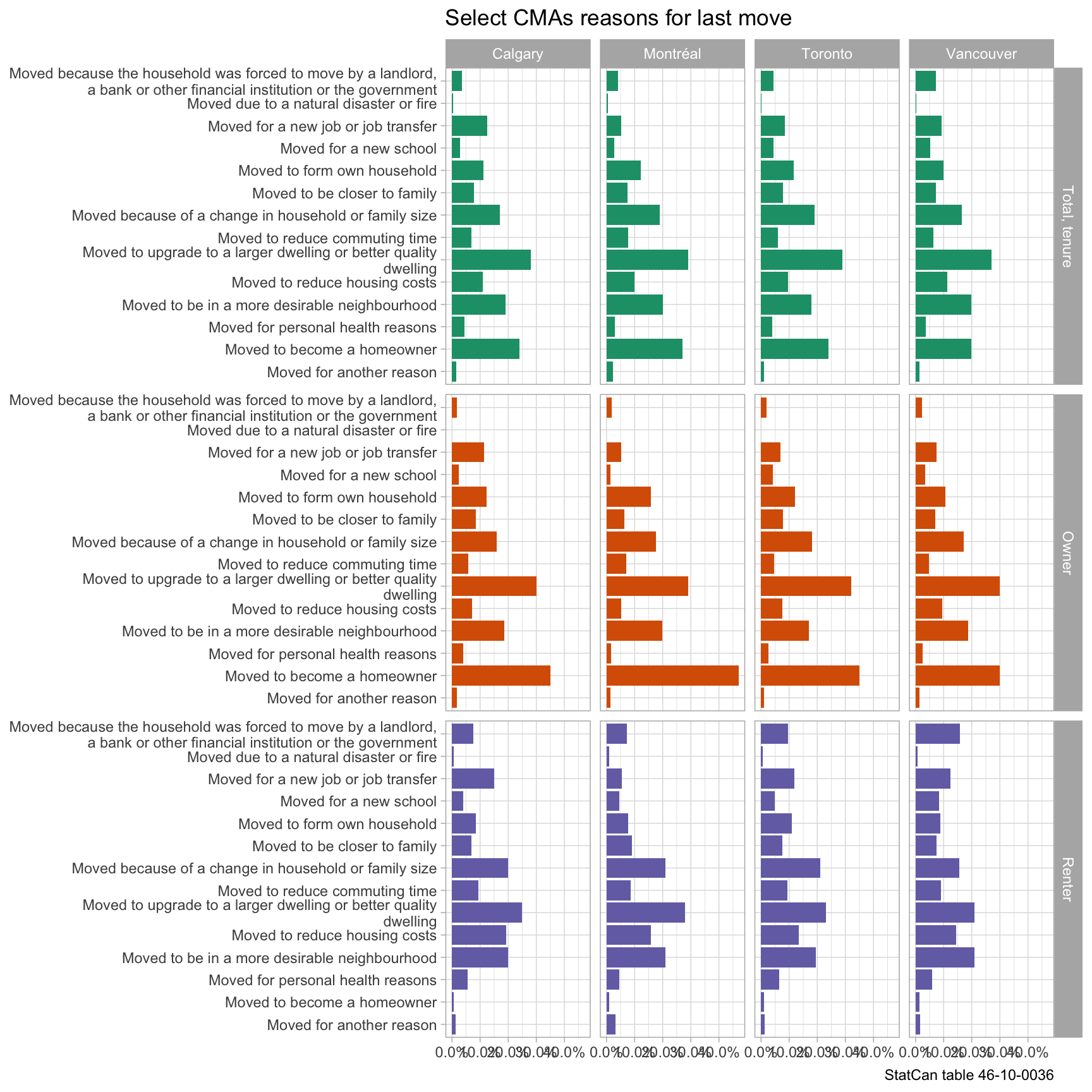

First to the question guide. Lots of good stuff here, but we’re interested in the questions about peoples’ previous residence: “People move for a variety of reasons, either voluntary or non-voluntary. Why did you move from your previous dwelling?” Importantly, respondents are allowed to choose more than one, and only the respondent (rather than other household members) counts. Let’s look at the proportion of people selecting each reason for their last move by metro and by current tenure.

Overall the reasons for moving is fairly uniform across major metro areas, with generally positive housing moves explaining most moves, as we’ve noted before. Hence people move to “upgrade” their dwelling in size or quality; to “become a homeowner”; and to “be in a more desirable neighbourhood.” More ambiguous housing moves, including those to “reduce housing costs”, vie with family-related moves (“change in family size”; “form own household”; “be closer to family”) and work-related moves (“new job”; “reduce commute”) as explanations.

Separating by current tenure (did people move into a place they rent or a place they own), the stories are still pretty similar. The first big takeaway is that mobility is pretty normal and common, and most people move for positive reasons. But there are a couple of notable differences. Moving “to reduce housing cost” or “to reduce commute time” factor more into renter’s than into homeowner’s decisions to move.

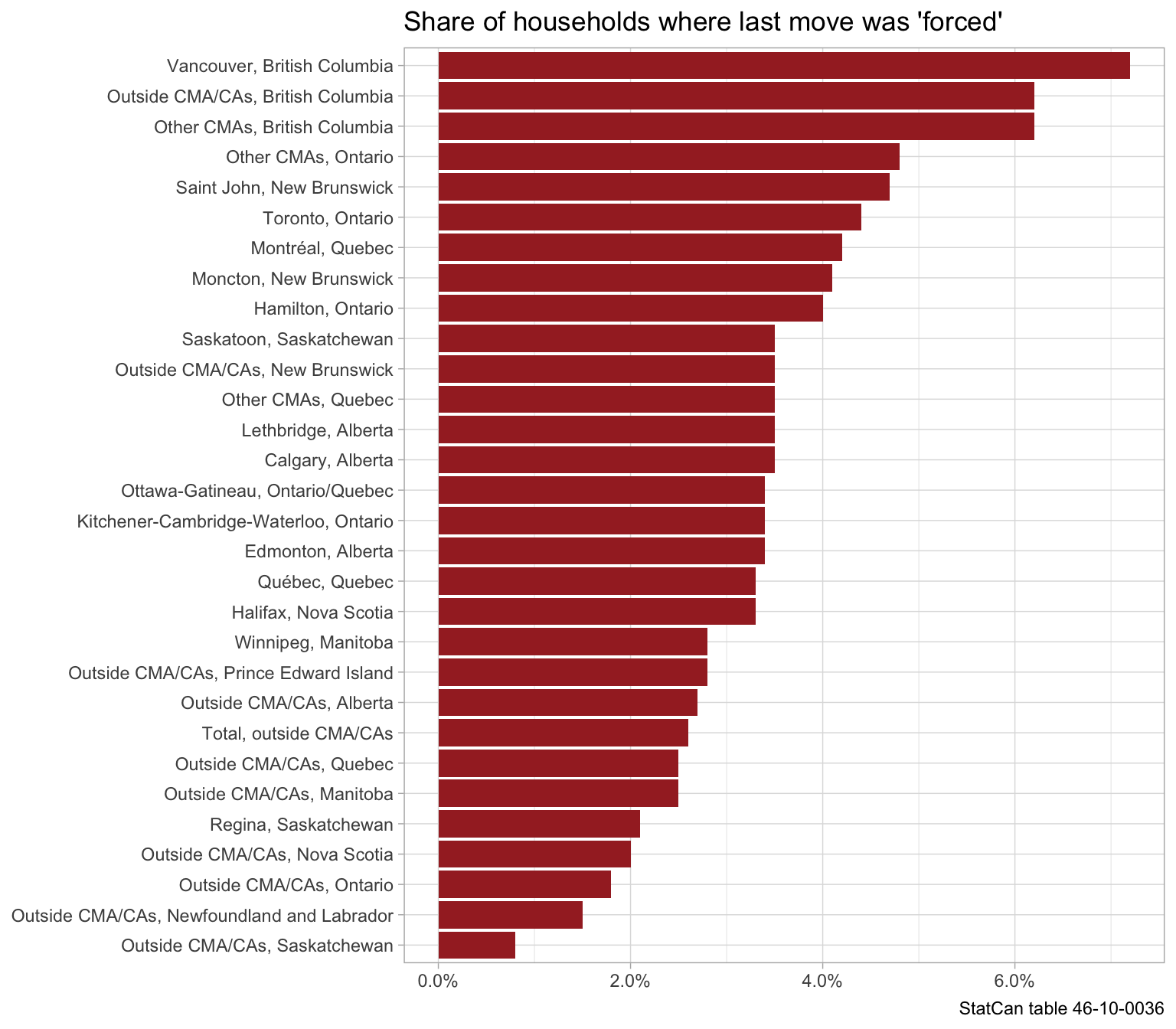

Finally, there’s are two reasons for moving that seem unambiguously negative for those involved, reflecting “forced moves.” One set of “forced moves” occur due to “natural disasters and fires.” The other comes down to social causes: “Because you were forced to move by a landlord, a bank or other financial institution or the government.” This happens far more often to renters and far more often in Metro Vancouver.

This brings us to the second big takeaway. In terms of forced moves, Vancouver sticks out like a sore thumb.

While Vancouver stands out, the other CMAs and rural areas in BC follow closely behind. Exposure to socially forced moves (e.g. evictions) seems to reflect something province-wide. Like our provincial protections for renters (Residential Tenancies Act) and how they’re enforced (or not) by the RTB. Or like our profound lack of rental options overall (low vacancy rates coupled with sometimes predatory landlords). Or like our heavy reliance upon the least secure kinds of rental stock (basement suites and condominium rentals) within secondary rental markets and subject to landlords reclaiming for their own use.

The results we have so far may reflect past conditions rather than the present. After all, we’re looking at peoples’ last moves here, many of which occurred more than five years ago. But we’ve got lots to follow up on in future analyses. And hopefully further releases from the CHS will clarify just what mechanisms are at work driving outsized displacement in Metro Vancouver.

As usual, the code for the post is available on GitHub for anyone interested.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{keep-on-moving.2020,

author = {Lauster, Nathan and {von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Keep on Moving},

date = {2020-01-24},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-01-24-keep-on-moving/},

langid = {en}

}