To help deal with the response effort in the recent Newfoundland and Labrador show storm, StatCan created vulnerability maps of the most affected areas. It’s great to see StatCan putting their data to use. After seeing this fly by on twitter and then flagged by Simon on Linkedin I had some thoughts on this that might be worth a quick blog post.

I am biased in how I think of these kind of disaster response maps via the tools that I have developed for working with StatCan census data, namely CensusMapper interactive mapping platform and the the cancensus R package.

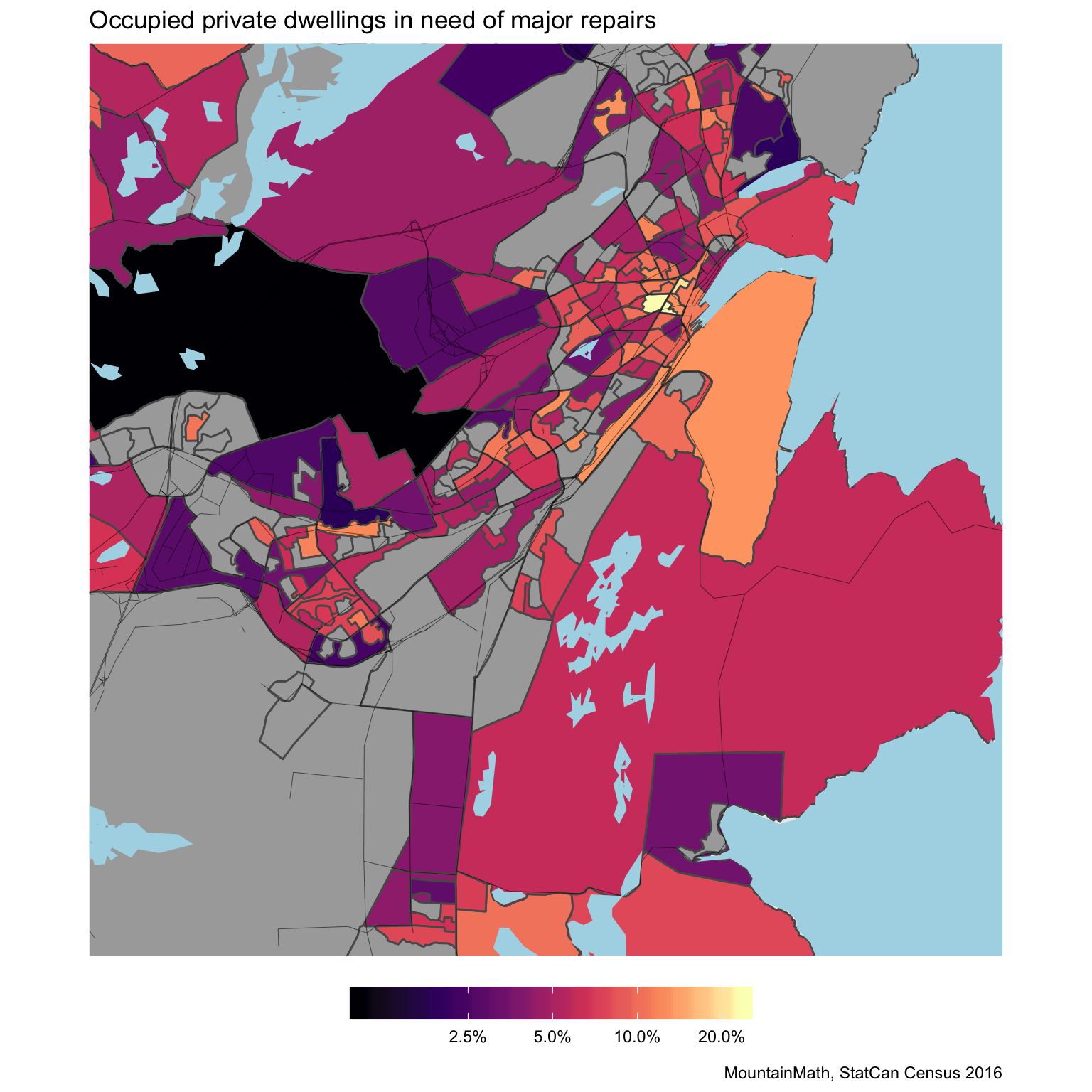

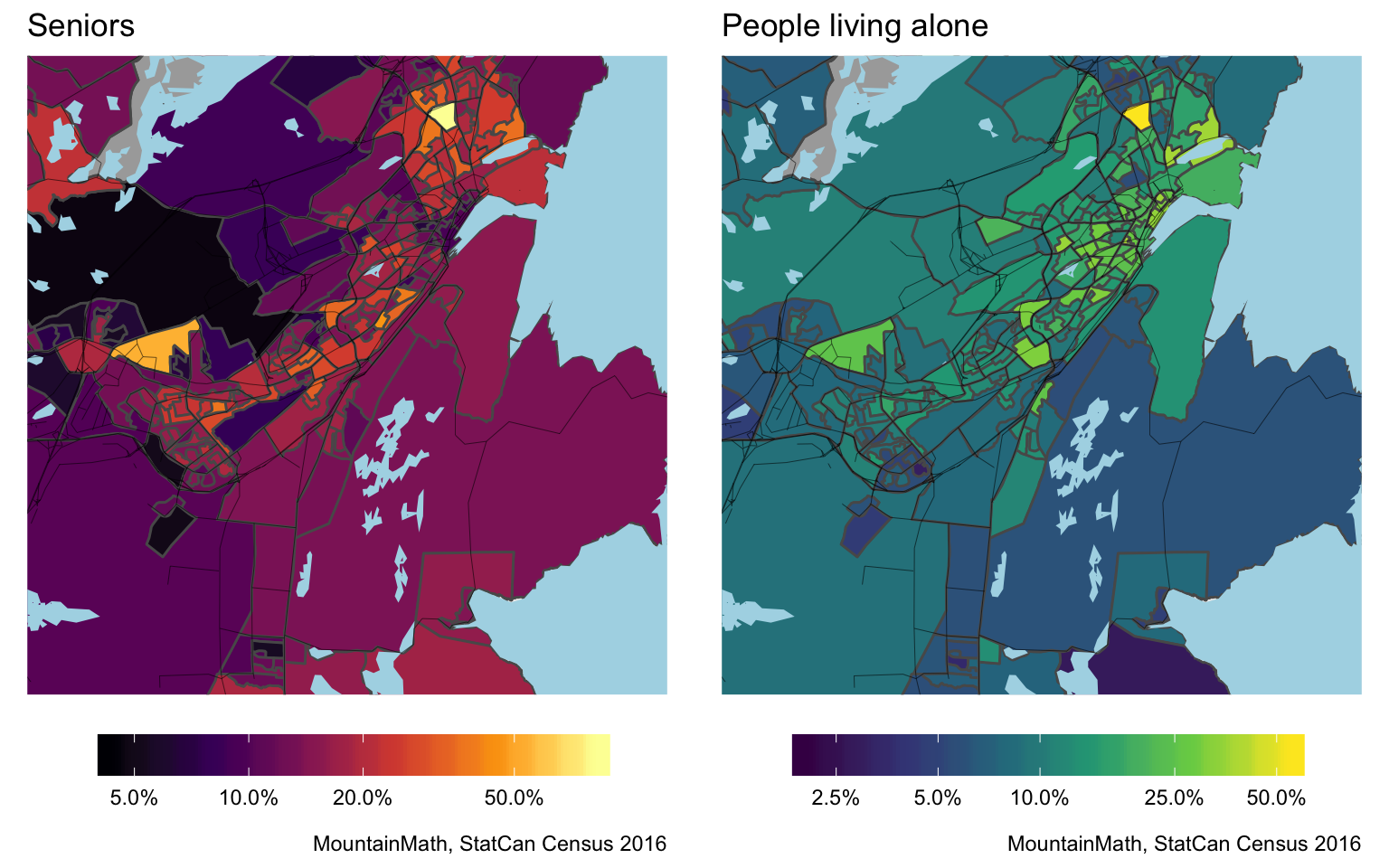

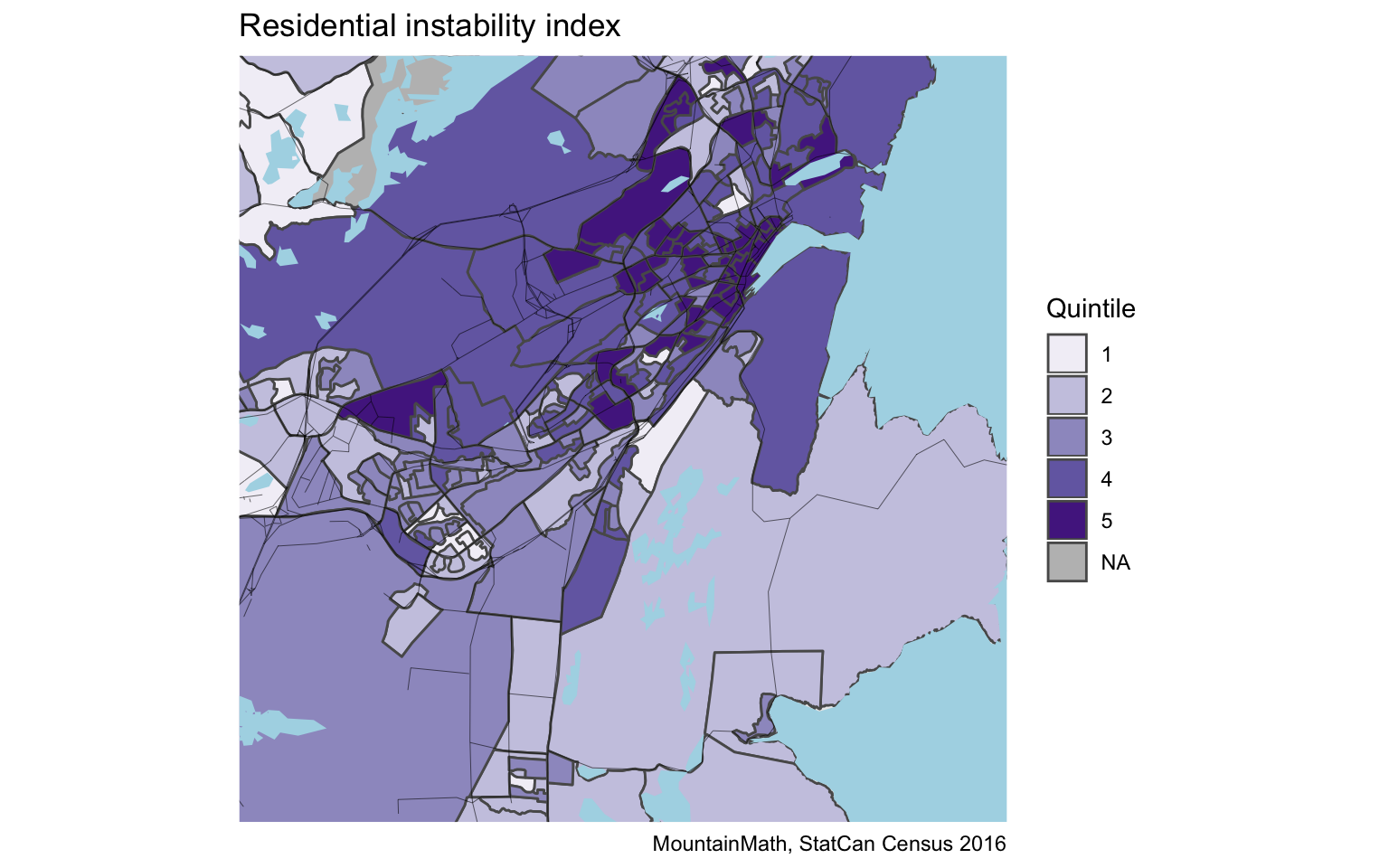

StatCan made four (PDF) maps, they mapped the share of seniors, share of people living along, share of buildings in disrepair and the Residential Instability Index. All of these are built on readily available census data, and the first three maps can be created as Canada-wide interactive maps in CensusMapper by anyone within minutes, as Simon pointed out. I have not imported the Canadian Index of Multiple Deprivation that underlies the maps, mostly because it was only done at the DA level hasn’t been pre-computed for higher aggregation levels that would be necessary for seamless mapping in CensusMapper. But there are other reasons which we will get to a little later.

Web maps aren’t always the best solution, paper maps have real value in a disaster region with possibly limited internet connectivity. Using the cancensus package we can create reproducible versions of the PDF maps that StatCan built. However, reproducibility is not that important, but these maps are very adaptable as a fringe benefit. We can easily produce the same maps for any other region in Canada by simply changing one line of code to shift the window of what we are mapping.

Let’s step through this process and see how to do this in CensusMapper and also using cancensus

CensusMapper

Everyone can make “simple” maps on CensusMapper. Simple maps are maps based on single census variables, or shares built off of single census variables. People can save maps and share them with others after singing up for a free account. Here is how this works:

CensusMapper maps are automatically Canada-wide, the geographic aggregation level that data is displayed at adjusts according to the zoom level. Maps for other census variables can be made the same way.

Cancensus

The cancensus package ties into the CensusMapper data APIs to facilitate targeted data import, analysis, and visualization in R. The CensusMapper API tool provides a GUI interface for region selection and variable discovery.

library(tidyverse)

library(cancensus)

census_data <- get_census(dataset='CA16', regions=list(CMA="10001"), geo_format='sf', level='DA',

vectors=c(disrepair="v_CA16_4872",seniors="v_CA16_244",

alone="v_CA16_419",pop_private_hh="v_CA16_424")) %>%

mutate(share_disrepair=disrepair/Households,

share_alone=alone/pop_private_hh,

share_senior=seniors/Population)

ggplot(census_data) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=share_disrepair)) +

st_johns_theme +

scale_fill_viridis_c(option = "magma",trans="log",

labels=scales::percent,breaks=c(0.01,0.025,0.05,0.1,0.2),

na.value = "darkgrey") +

labs(title="Occupied private dwellings in need of major repairs",fill=NULL)

We can similarly produce the other two maps.

Residential Instability Index

plot_data <- census_data %>%

left_join(get_multiple_deprivation_index_data(),by="GeoUID")

ggplot(plot_data) +

geom_sf(aes(fill=as.character(`Residential instability Quintiles`))) +

st_johns_theme2 +

scale_fill_brewer(palette = "Purples",na.value="grey") +

labs(title="Residential instability index",fill="Quintile")

But what’s behind the Residential Instability Index? It’s a superposition of several census variables:

- Proportion apartment housing units

- Proportion of dwellings that are owned

- Proportion living alone

- Proportion of residential mobility (same house as 5 years ago)

- Proportion of the population that is married/common-law

Unfortunately the StatCan user guide does not detail the proportions used to generate the index. Knowing these would make it trivial to map the index Canada-wide on CensusMapper. This is another reason why we have not added the Multiple Deprivation data, it does not add much new data. The only thing we are missing is the handful of weights and the quintile binning.

Upshot

The StatCan maps used for the disaster recovery effort can already be built by anyone within minutes. Using CensusMapper to generate interactive Canada-wide web maps, or using cancensus to generate print-quality maps. Using cancensus we also have the advantage of having reproducible code that can be easily adapted for any other region in Canada. All that’s needed is to switch out the region we pull the census data from and the bounding box we want to restrict the map view to. We could work a little harder to add annotations, or switch over to a desktop GIS software and spent time styling the map in more detail if that’s desirable. There is no added value to have StatCan do this work.

Opportunities

Where StatCan could add tremendous value however is to generate a Deprivation Index that is built up from individual level census data to estimate vulnerability. Take the example of our first three maps, looking at senior population, people living alone and buildings in disrepair. Imagine one DA with a third of the population seniors, a third of the population living alone and a third of the dwelling units in disrepair. How vulnerable is the population in that area? It depends.

If most of the seniors live in extended families, most of the people living alone are students in apartments, and most of the homes in disrepair are taken up by working age couples, things aren’t too bad. Lots of people are vulnerable in some way, but probably have enough resources to deal with things to some extent.

But if most of the seniors are living alone in homes in disrepair, we have a real problem. The other thirds of the population are doing fairly well, but that one third is extremely vulnerable and probably need help fast.

Looking at single variables and overlaying them in some way, including the way it’s done in the Multiple Deprivation dataset, can’t identify the severity of the vulnerability faced by some people, and severity really matters. But StatCan does have the means to build up an index that looks at severity, but leveraging access to individual level census data. We already do this for example in the definition of Core Housing Need, where we also separate out how many people fail to meet at least one of the housing standards, and how many fail to meet two or all three. Which gives a measure of severity.

Similarly, StatCan could look at how many people fail one vulnerability metric, and how many fail two or three or more at the same time. This gives us a much better picture of vulnerability that can guide recovery operations.

Outdated data

Another point to mention is that the census data is now almost 4 years old. It still can serve as a decent proxy in areas that did not change too much, but using these maps we will be flying in the dark in areas where lots of new development came in. We are working on ways to make census data more up-to-date, more on that soon. Construction data, as well as annual tax data can both play a role here. But this will only work well for some metrics, and is harder to do for others. And our upcoming project only goes down to census tract level geographies, which is of limited use in disaster recovery efforts. This provides yet another opportunity for StatCan to show leadership and leverage their much better data.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub if others want to adapt this for their own purposes.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{disaster-response-maps.2020,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Disaster Response Maps},

date = {2020-02-02},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-02-02-disaster-response-maps/},

langid = {en}

}