(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

Empty homes are in the news again in West Vancouver after a West Vancouver council motion asking the province for the power to levy their own Speculation and Vacancy tax.

THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED THAT the Provincial Government provide local governments with the power to levy their own Speculation and Vacancy Tax, so that they too can address housing affordability and other community effects of vacant homes.

West Vancouver seems interested in the empty homes and not the satellite family component of the SVT, which may well be a wise choice given how messy and problematic a law defined based on spousal relationship can get.

The motion is interesting for several reasons, not just because of the focus on vacancy vs satellite families. It sets the stage by naming housing affordability as a key challenge.

WHEREAS housing affordability is a key challenge in many municipalities but particularly in the District of West Vancouver with a median house price of $2.5 million, and a rental vacancy rate of 1.2%;

As evidence the motion rightly points at the low rental vacancy rate. The ownership metric is curious though as it explicitly focuses on “houses”, excluding more affordable multi-family units from consideration. This is likely no accident, as West Vancouver has a solid track record of focusing their energy on the most expensive type of housing by permitting fewer multi-family homes than more expensive single-detached houses to be built, the latter of which often just replace older single-detached homes and do not add to the dwelling stock.

The next part reads:

AND WHEREAS according to the 2016 Census, approximately 1700 homes, or almost 10% of dwellings in West Vancouver, were identified as “unoccupied”;

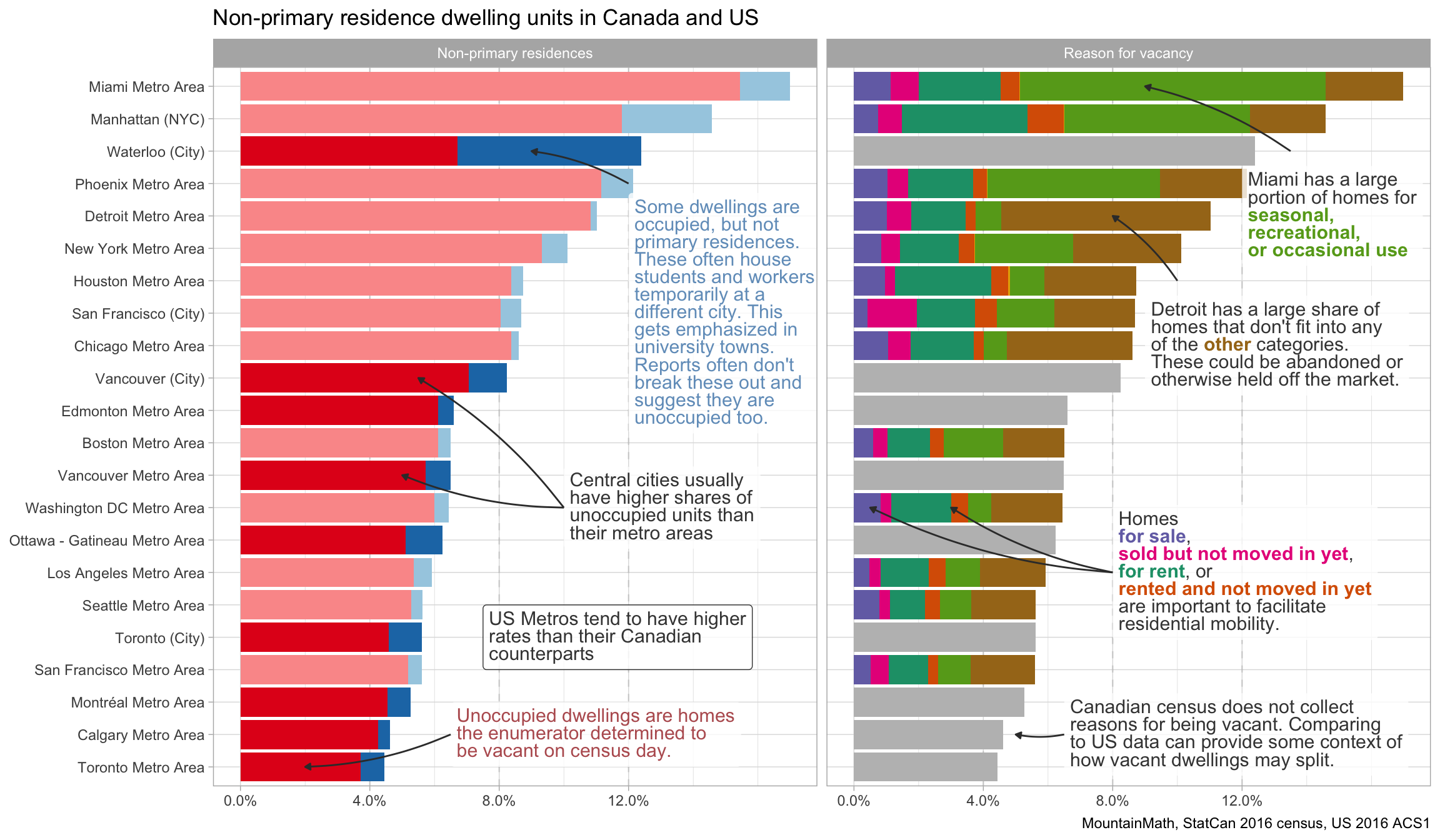

This is incorrect, the 2016 census enumerated 1,525 unoccupied dwelling units in West Vancouver, comprising 8.2% of the total dwelling stock. Council is only partially to blame for this misstatement, reporting on this census metric has generally been sub-optimal, to say it politely. The problem is not just about getting the number right, but more importantly understanding what the numbers mean. The census enumerates homes that are empty on census day, and homes can be empty for several reasons. Some of which are mundane and even desirable, just one “whereas” ago it looked like council wanted more unoccupied homes – that are available for rent. There are other categories of unoccupied homes that are important in enabling residential mobility, homes that are rented but not moved in yet, homes that are for sale and unoccupied or bought and not moved in yet. The US ACS tries to track down reasons why homes are unoccupied, it can be instructional to use that as base of comparison when looking at Canadian data as in the following graph based on some of our past joint work.

Being unoccupied on a particular day, for example Census day, does not give direct information about homes that might be targeted by an empty homes tax. The list of exemptions in Vancouver’s Empty Homes Tax or the provincial Speculation and Vacancy Tax opens another window into reasons why homes may be empty.

We can further break down the unoccupied homes the census found in West Vancouver by structural type.

In West Vancouver, most homes registering as unoccupied are single family homes, followed by units in suited single family homes that the census refers to as “Apartment or flat in a duplex”. This is to a large degree due to the building stock that leans heavily on single-detached homes. The two dwelling types have also been responsible for most of the growth in homes classified as unoccupied in the census.

It is helpful to also look at shares of homes in each type that registered as unoccupied, and put in context with the Metro Vancouver shares.

The shares of unoccupied homes are generally higher in West Vancouver, with the exception of row houses and highrise apartments. The shift in row houses is fairly recent, and should probably not be over-interepreted because of the small overall number of row homes. The difference in rates of unoccupied highrises likely stems from a relatively high share of rental highrises in West Vancouver.

The high share of unoccupied “duplex” units stands out. Recall that in Metro Vancouver units classified as “duplex” by the census are mostly suited single family homes. These register with the highest share of unoccupied homes throughout Vancouver, which is driven by empty secondary suites in such houses. Incidentally, secondary suites are exempt from both the City of Vancouver Empty Homes Tax and the provincial SVT.

In all of this it is important to remember that census unoccupied counts were taken back in 2016, before these taxes came into effect, and some owners will likely have changed their behaviour because of the tax and rented out or sold their previously empty home. Indeed, we now have a much more recent and much better defined dataset predicting how many problem empties are likely to be taxed by an Empty Homes Tax in West Vancouver. That dataset comes from the Speculation and Vacancy Tax itself. Worth noting: we are still in the pre-audit phase for the SVT and it is not clear how many owners are trying to dodge the tax by declaring incorrectly. But setting aside Satellite Families (where homes aren’t empty), the SVT numbers for the City of Vancouver aren’t very different from the City of Vancouver Empty Homes Tax numbers, where we are now in the third year and already have two years of complete declarations and audit cycles. So far so good.

Bottom line is that a much more reasonable expectation of the number of homes that may be targeted by a West Vancouver empty homes tax at this point is around 221, the number of vacant homes paying the SVT.

The next two whereas speak to revenue expectations.

AND WHEREAS the Province reported that in 2018, $58 million was collected under the Speculation and Vacancy Tax program, and that $6.6 million of that was collected from West Vancouver homeowners;

AND WHEREAS the Province of British Columbia gave the City of Vancouver the power to impose its own vacancy tax which has provided Vancouver with approximately $40 million in additional revenue;

The $6.6 million cited as being collected from West Vancouver covers both, vacant homes and homes occupied by satellite families. Only $4.1 million was collected for vacant homes in West Vancouver. The comparison the the City of Vancouver tax is somewhat irrelevant to this discussion, other than stressing again that revenue expectations is an important driver of this motion. One should note here too that the tax rate West Vancouver could charge for vacant homes is limited by a very simple calculus. Once the combined tax rate of municipal and SVT vacancy taxes exceeds the property transfer tax, owners can trigger a sale to e.g. a relative in order to pay the lower property transfer tax and be exempted from the vacancy taxes, with all the revenue accruing to the province. The City of Vancouver has hiked their Empty Homes Tax rate and is slowly approaching this limit.

Upshot

An Empty Homes Tax can be useful. It incentivizes better use of property by returning some unproductive properties back into the rental or ownership market. It generates revenue in case people are unwilling to rent out their mostly unoccupied home.

But it also comes at a cost, it can be intrusive and there are always edge cases. And it takes a sustained effort to administer fairly.

We believe that in the case of the Vancouver region the benefits generally outweigh the costs at this time. We can imagine that we might come to a different conclusion if e.g. the rental vacancy rate climbed up above 3%, but we don’t see a medium-term path leading to that.

Looking back at the City of Vancouver’s experience it seems prudent to approach an Empty Homes Tax with realistic expectations. In the City of Vancouver our Former Mayor said that the tax could free up as many as 25,000 empty units for rent, an unfortunate statement that raised expectations unreasonably high and is still being brought up when people criticize City staff for their EHT numbers not measuring up to lofty promises

The bottom line is that clear and realistic expectations are an important part of a successful implementation. It is good politics, and City staff will thank their politicians for this.

As usual, the code for the analysis is available on GitHub.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{knock-knock-anybody-home.2020,

author = {Lauster, Nathan and {von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Knock {Knock,} {Anybody} {Home?}},

date = {2020-03-09},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-03-09-knock-knock-anybody-home/},

langid = {en}

}