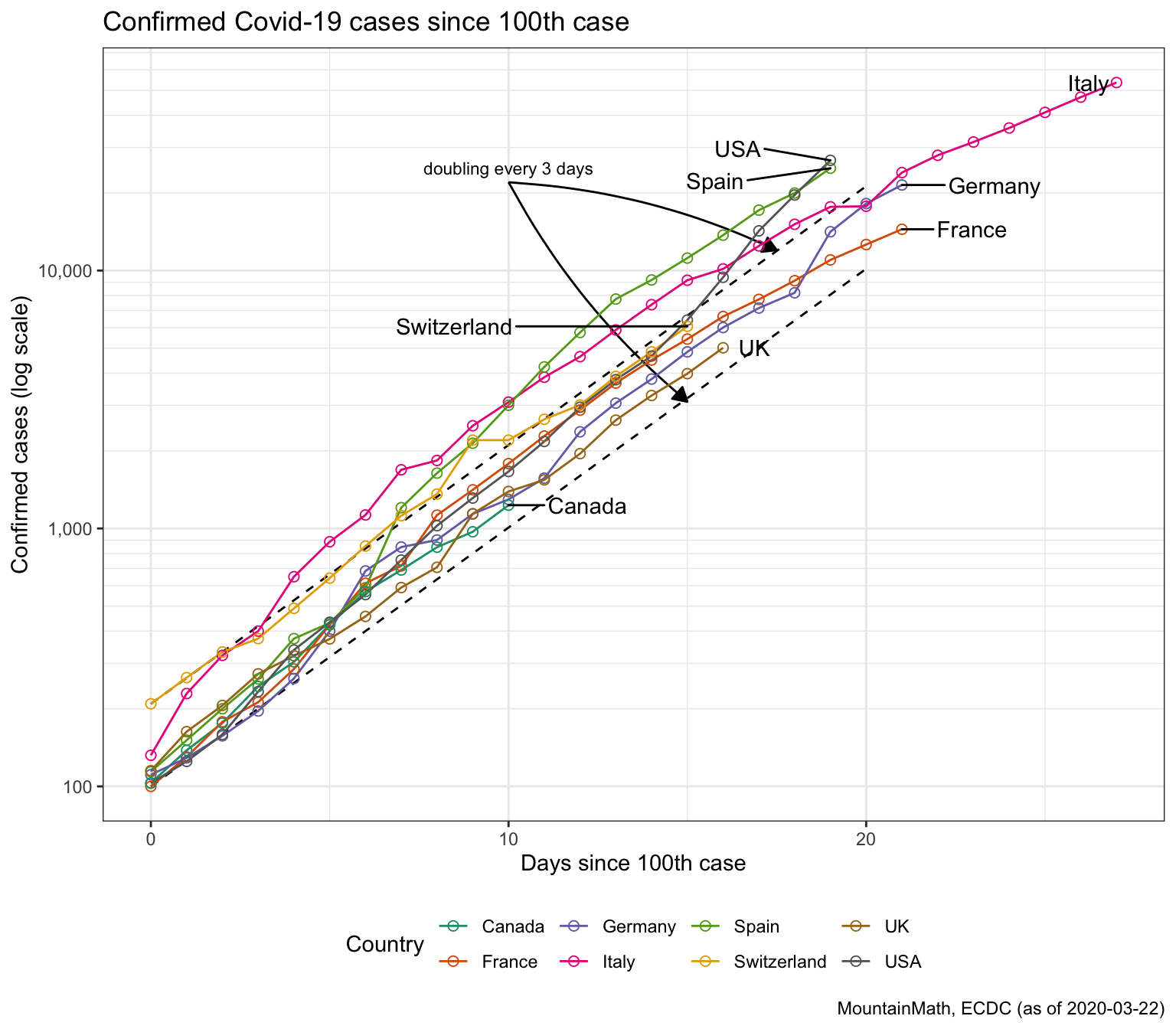

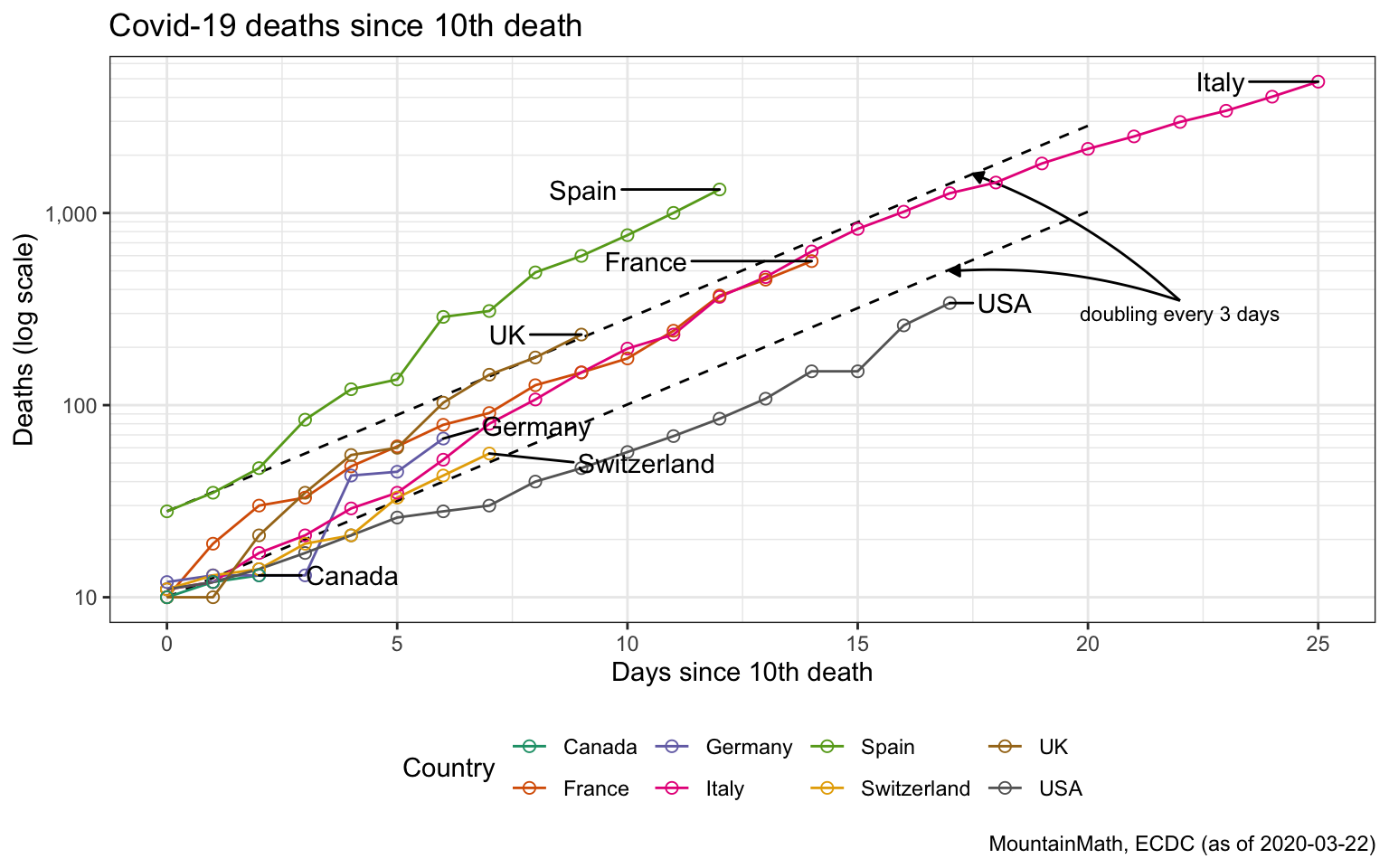

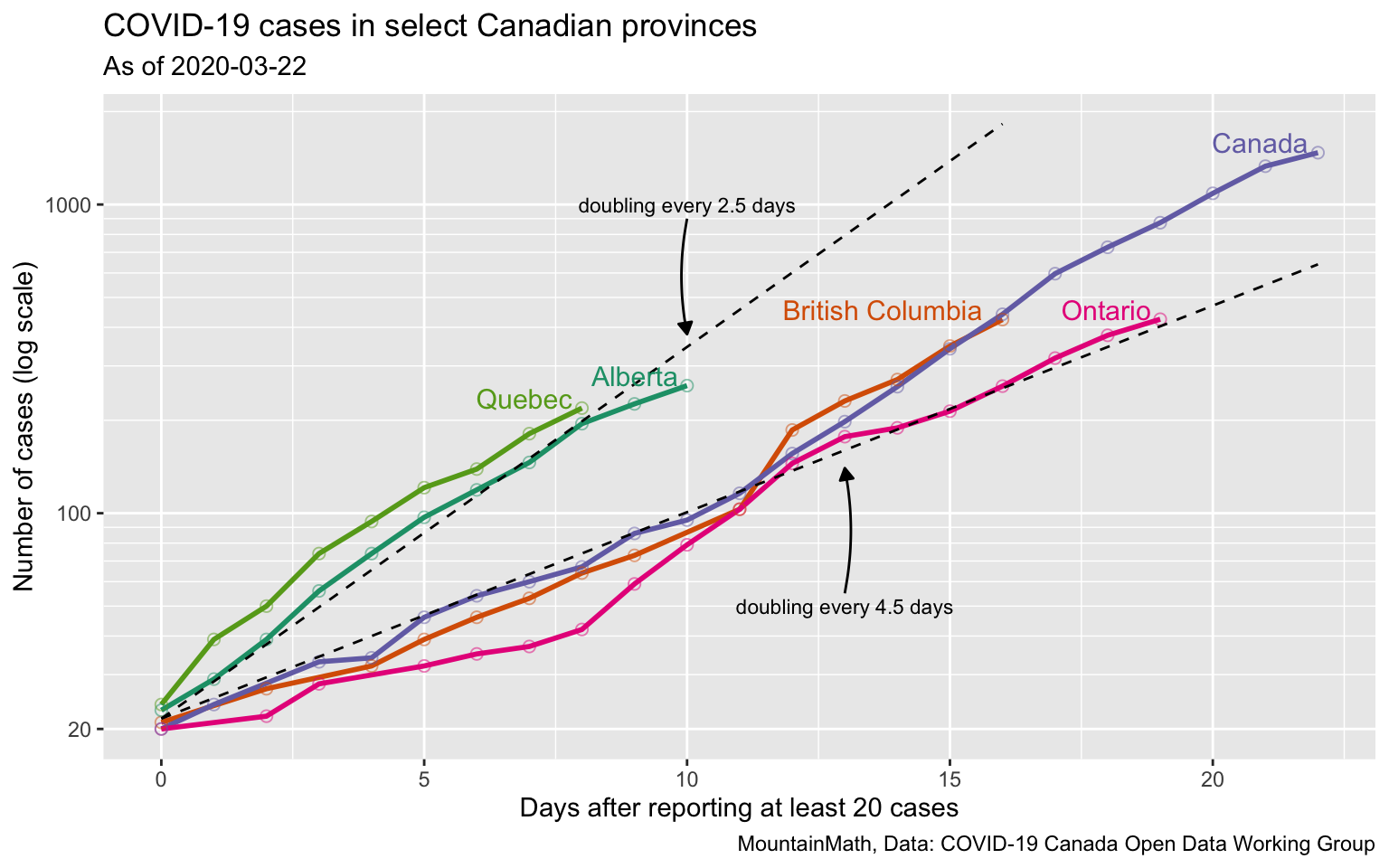

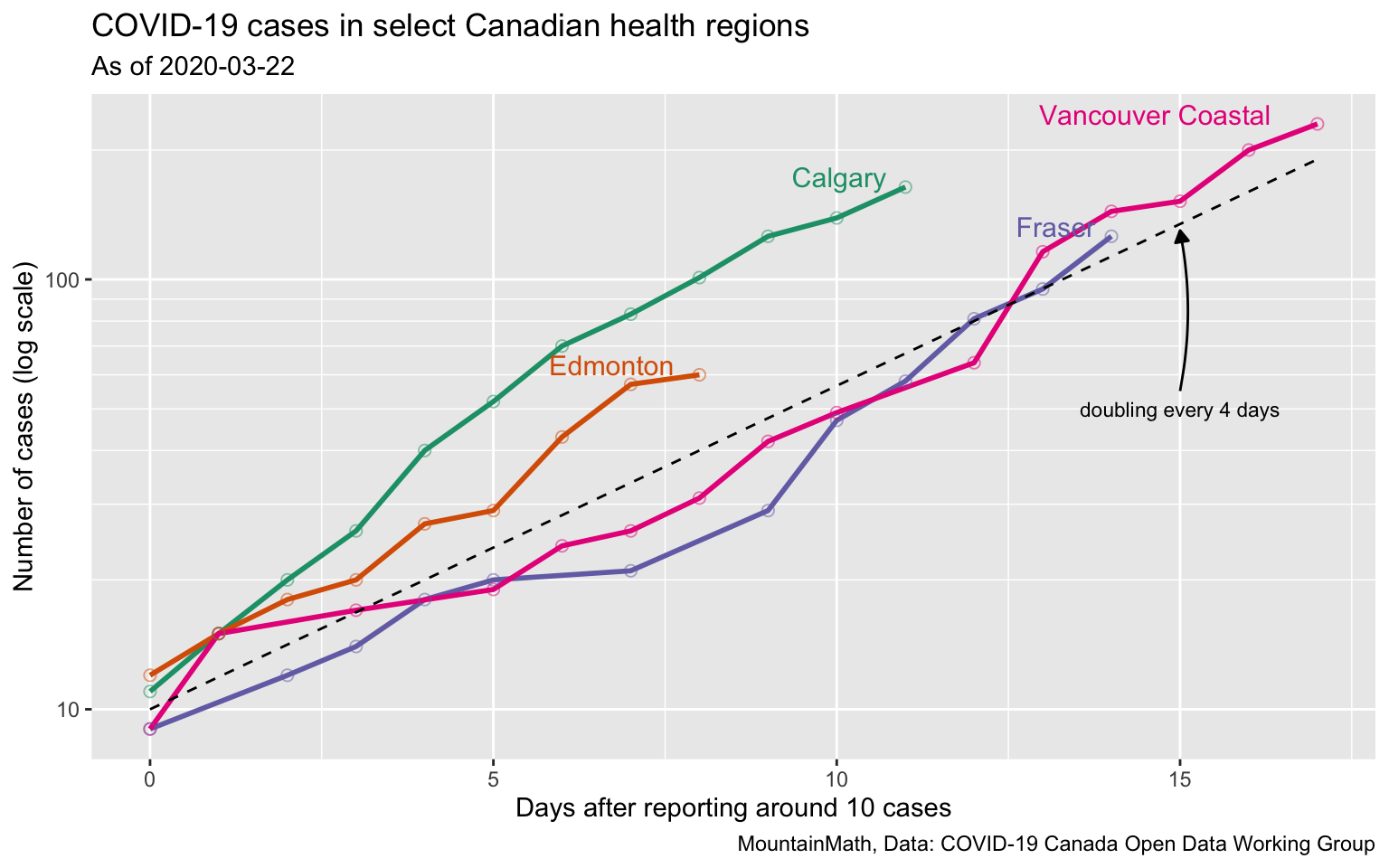

With COVID-19 cases growing exponentially, Canada has introduced sweeping restrictions to curb the spread of the virus. People are asked to practice social distancing, work from home if possible, keep shopping trips to a minimum, keep a distance of at least 6 feet to people outside of their household, universities and schools have been closed, and travel has been restricted.

The solution

To deal with the virus we need to slow down the growth rate, ideally to zero. In absence of having a vaccine, our only way to do this is to change people’s behaviour. If people stay away from each other, wash their hands with soap regularly, and don’t touch their face, the growth rate can be slowed down significantly. That’s the idea behind social distancing. But changing behaviour is hard, and the ways people respond to calls for social distancing varies.

As we have seen in Europe, and are now seeing in Canada, government will impose successively more restrictive conditions when people don’t follow the social distancing guidelines. And all of this costs time. Time we don’t have.

The laggy steering wheel

We have seen early on in the example of Wuhan that measures we are implementing today will only become visible in the data in about two weeks in the future.

It should take 2 weeks for shutdowns/distancing to show up in the case numbers, if China is any guide. pic.twitter.com/5qyl0aZfxn

— Noah Smith 🐇 (@Noahpinion) March 21, 2020

Changes in behaviour today means the number of people getting infected tomorrow will be lower than otherwise. These infected people won’t develop symptoms until after on average 5 days, sometimes it can take up to 14 days. These people may watch the symptoms for a couple of days (hopefully self-isolating) until they request a test. Depending on the local protocol, they will get tested within a couple of days. Then it takes a couple of days for the results to come in and get reported (BC did not report any cases yesterday, we will have to wait until 10 am Monday to get the update for Sunday), and then make it into the data feeds and the newspapers for people to see. In other words, we don’t know how effective our behaviour change is until two weeks later.

The New York Times has a great article highlighting Italy’s journey to more effective social distancing. People tend to react to what they see right now and aren’t wired to react today to what we expect to see in two weeks time.

There are several ways to attack this problem. One is to do a better job explaining why we act now while the numbers still seem relatively low. Another is to reduce the time it takes for infected people to enter the official statistics. We can encourage people to seek testing earlier and increase the turnaround time for tests and set up live centralized data feeds for reporting new cases that makes it easy for news outlets to report in a timely manner.

In the meantime we should find alternative live measure of behaviour change. Italy has used cell phone mobility data to understand population-level compliance with social distancing.

Traffic As a Live Measure

One way to measure real-time behaviour change is to look at traffic. People have already been looking at change in congestion as a metric for how people change behaviour due to COVID-19, others have looked at changes in transit ridership.

Here in Vancouver we can also look at congestion, but it is hard do estimate changes in traffic from changes in congestion. TransLink aggregate ridership data has a significant lag and only monthly temporal resolution, so it isn’t useful for this.

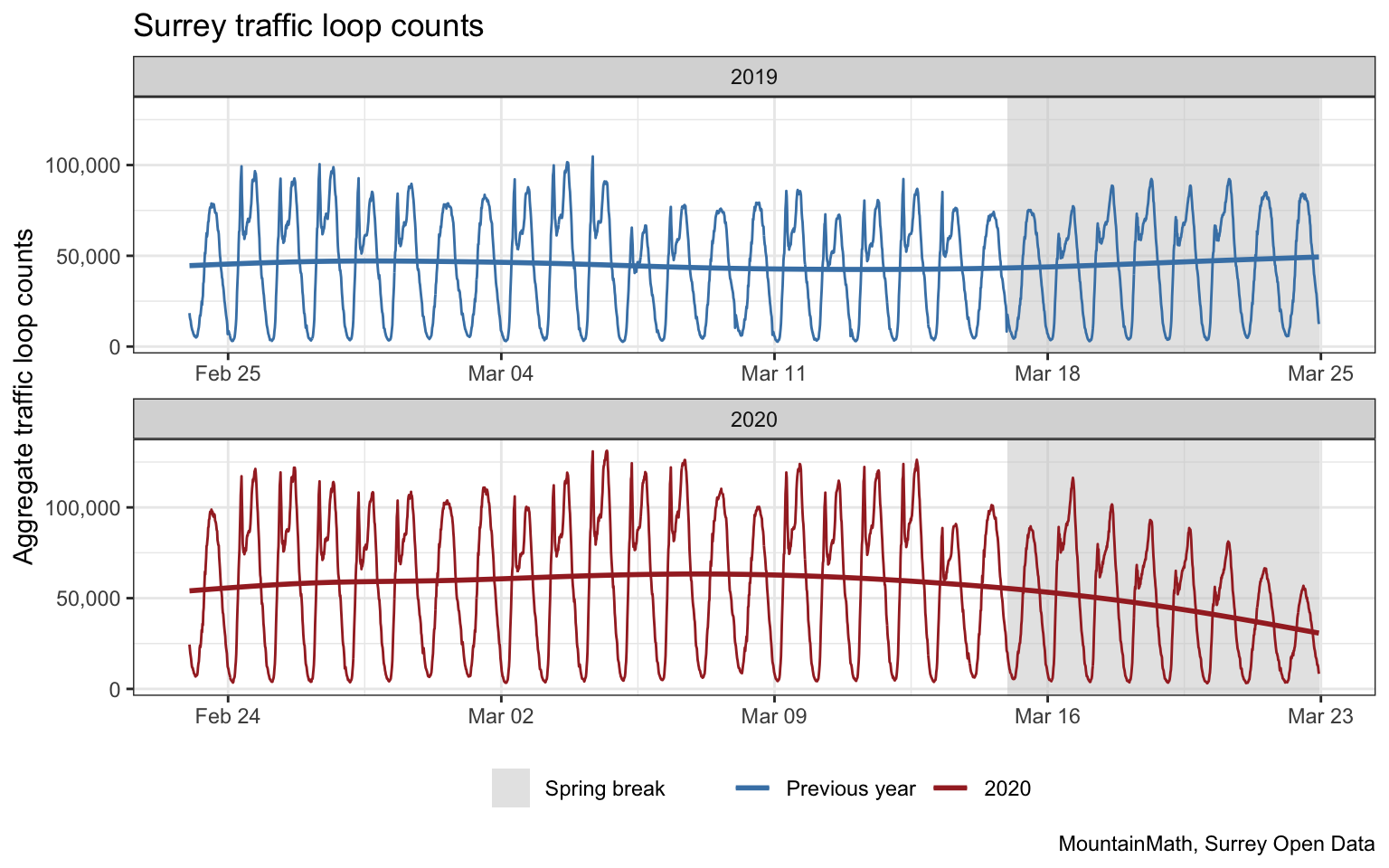

A good way to understand change in traffic due to COVID-19 is to look at traffic loop counts. Surrey Open Data makes traffic loop counts available. We already looked at this to estimate the traffic impact of school dropoff and pickup traffic.

We see that overall 2020 traffic levels were higher than 2019 levels, but that reversed in the past week when 2020 traffic levels dropped.

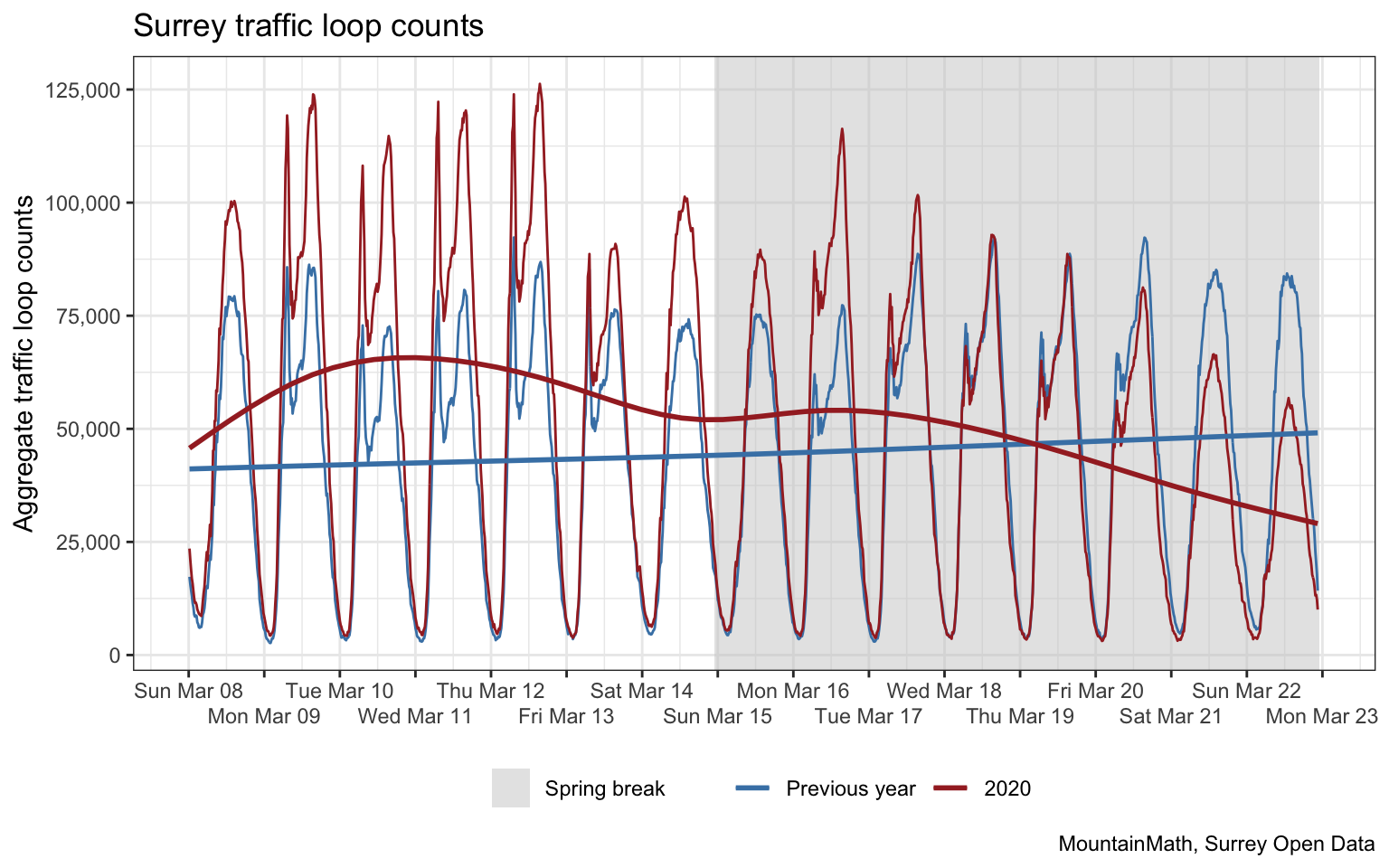

To compare this more easily we can shift the 2019 data forward so that the respective spring break periods match up plot both on the same graph, focusing in on the past two weeks.

Here we see how social distancing has evolved over time. We observe how the 2020 numbers change from exceeding 2019 traffic counts before the spring break weekend to increasing falling below them during the first week of spring break.

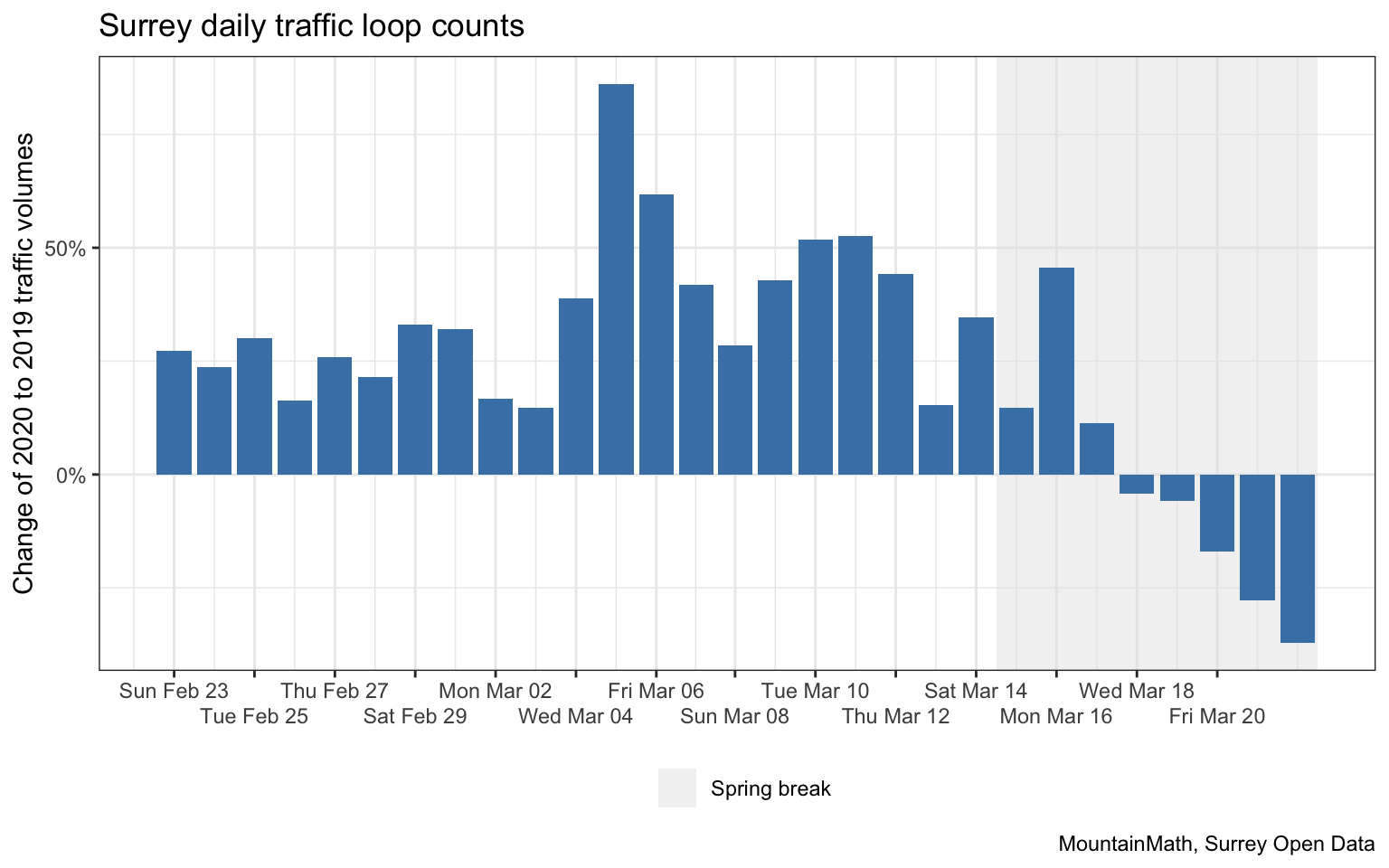

We can zoom into that even further by computing the percent change in traffic compared to last year and see how that changes over time.

There is quite a bit of volatility in the data, with a clear successive decrease in traffic volumes in the past week. Behaviour change takes time for people to follow through with, and increasing government restrictions facilitate this too.

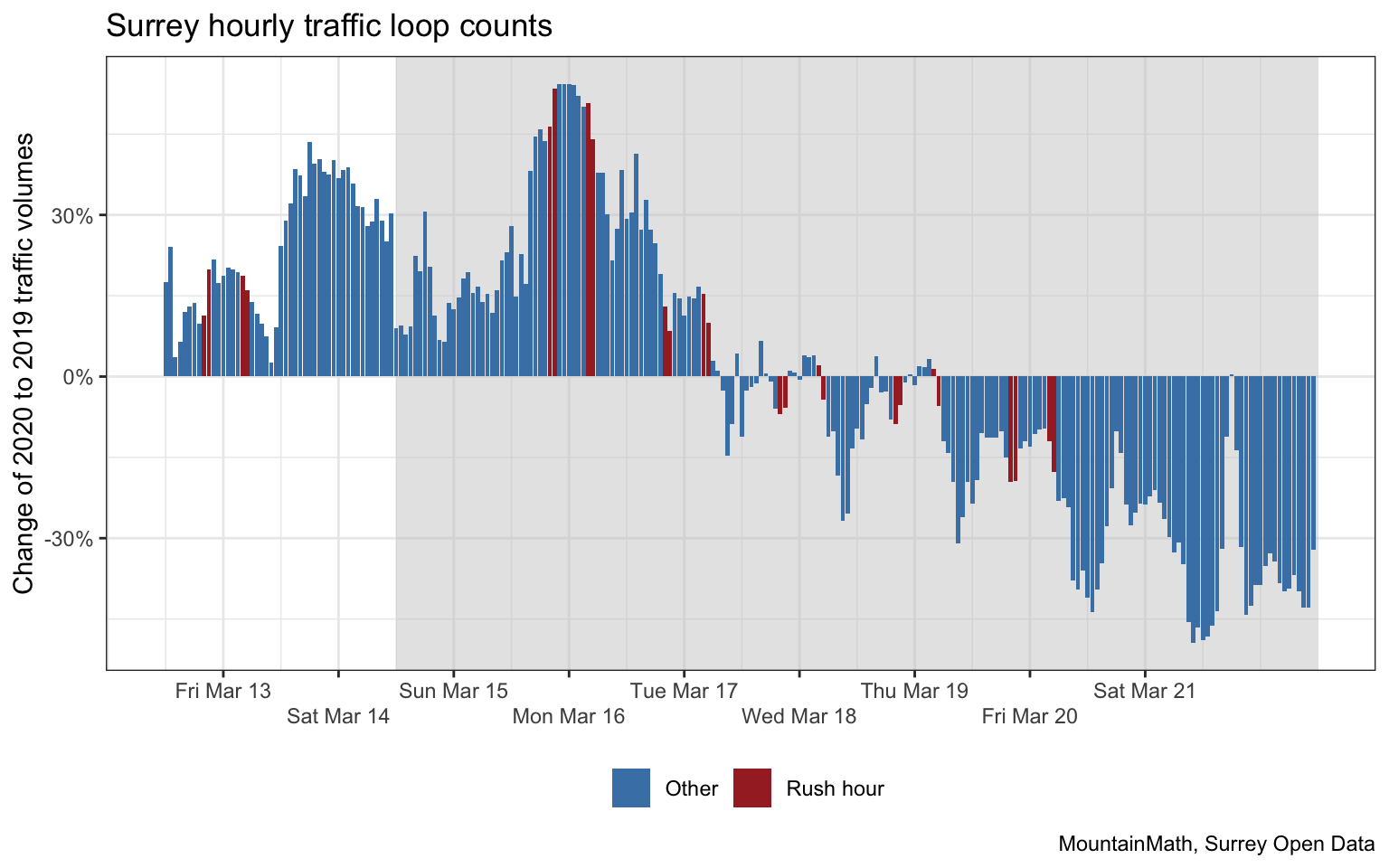

An interesting observation here is that commuting (rush hour) traffic is reduced by at least as much as non-commuting traffic. On the surface this contradicts the observation by John Burn-Murdoch that rush hour congestion decreased more than discresionary (midday) traffic in some cities. But those two might be reconciled by the fact that reduction in “congestion”, as measured by TomTom, is quite different from measuring a reduction in traffic volumes. Removing even a small percentage of traffic at rush hour will lead to a much larger reduction of travel speeds than removing the same share at midday. The coming weeks will tell if this was just a part of the slow adapting to social distancing and midday travel will eventually drop by more than commute traffic.

Upshot

Slowing the spread of the virus is extremely important. And we have to do this while the numbers are still relatively small and the health system is not yet completely overwhelmed. Change is hard when there is such a large gap between behaviour changes and when we will see the results. We need to closely monitor how well people’s behaviour changes at the population level. It’s only a proxy metric for how we are doing in fighting the virus, but we get immediate feedback to guide if governments needs to increase restrictions to further force behaviour change.

Some behaviour change, or lack thereof, is obvious. The images and videos of people playing basketball or soccer, having parties at the beach, or failing to practice appropriate social distancing walking along the crowded seawall, all are making the rounds on social media, and are testament to that. It is understandable that it can be hard to extrapolate individuals’ behaviour to the population level, it’s hard to quantify the extent of it. We need more systematic ways of tracking this, relying on social media reports to bubble up and trigger piecemeal action is better than nothing, but it’s a far cry from a holistic response. That’s where metrics like traffic patterns, or even better, cell phone mobility data as used in Italy, become useful. They tell us at the population level how well social distancing is practised.

Not everything can be monitored, and not everything needs to be monitored. A selection of several key metrics would probably suffice to get a good holistic picture.

For example, Taiwan will monitor compliance with self-quarantine rules for travellers and other people needing to self-quarantine by monitoring their cell phone location. These measures may seem overly intrusive, but they have, together with a host of other measures, enabled Taiwan to keep schools open and people going to work as normal.

There are countries that go even further and conduct individual level monitoring. Epidemological models of the virus tell us that interventions like social distancing will have to be kept up for very long times, otherwise we will again end up with rising cases. Democratic countries like Taiwan and Singapore have shown that there are other ways to keep the virus in check. Both countries have massive population hygiene education campaigns facilitating collective behaviour change, including measuring temperature prior to leaving home for school or work, temperature measurements before entering stores or large public spaces, submitting to intrusive surveillance of self-quarantine of all incoming travellers, and combining mobility data with aggressive (and intrusive) data-driven contact tracing. These intrusive measures buy other freedoms, kids can go to school, people can go to work and life functions somewhat normally.

Right now we are sacrificing basic freedom of movement and assembly, freedom to go to school or to work. Taiwan and Singapore show that we can regain some of these by giving up other freedoms and submitting to some level of surveillance. Behaviour change is key, but on top of that we need to make tough choices what freedoms we are willing to give up and which ones to keep. At least until we have a vaccine available that can be safely deployed at scale.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{behaviour-change-in-response-to-covid-19.2020,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Behaviour Change in Response to {COVID-19}},

date = {2020-03-22},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-03-22-behaviour-change-in-response-to-covid-19/},

langid = {en}

}