We are growing increasingly concerned with the COVID-19 situation in BC. In particular the way there seems to be no strategy or goal to stop rising case numbers, and the relativism that excuses this by pointing to other provinces and countries that are doing worse. At upward of 150 cases a day we are looking at an average of one death a day and unknown numbers, likely in the mid to high two digits, with long lasting morbidity due to a COVID-19 infection.

What’s our goal?

The basic fact is that at some point we will have to act to at least stop the current growth, if not reduce current daily case counts. So what’s the right level of daily cases at which we should stop the growth? There is no reason to believe that stopping the growth at 10 cases a day, like we had in late spring, is any harder than stopping the spread at 150, or 200, or 500 cases a day. And given that TTI (test-trace-isolate) resources are limited, there is good reason to believe that stopping the growth gets harder the longer we wait. Which begs the question why we wait. And also, why we don’t aim for zero.

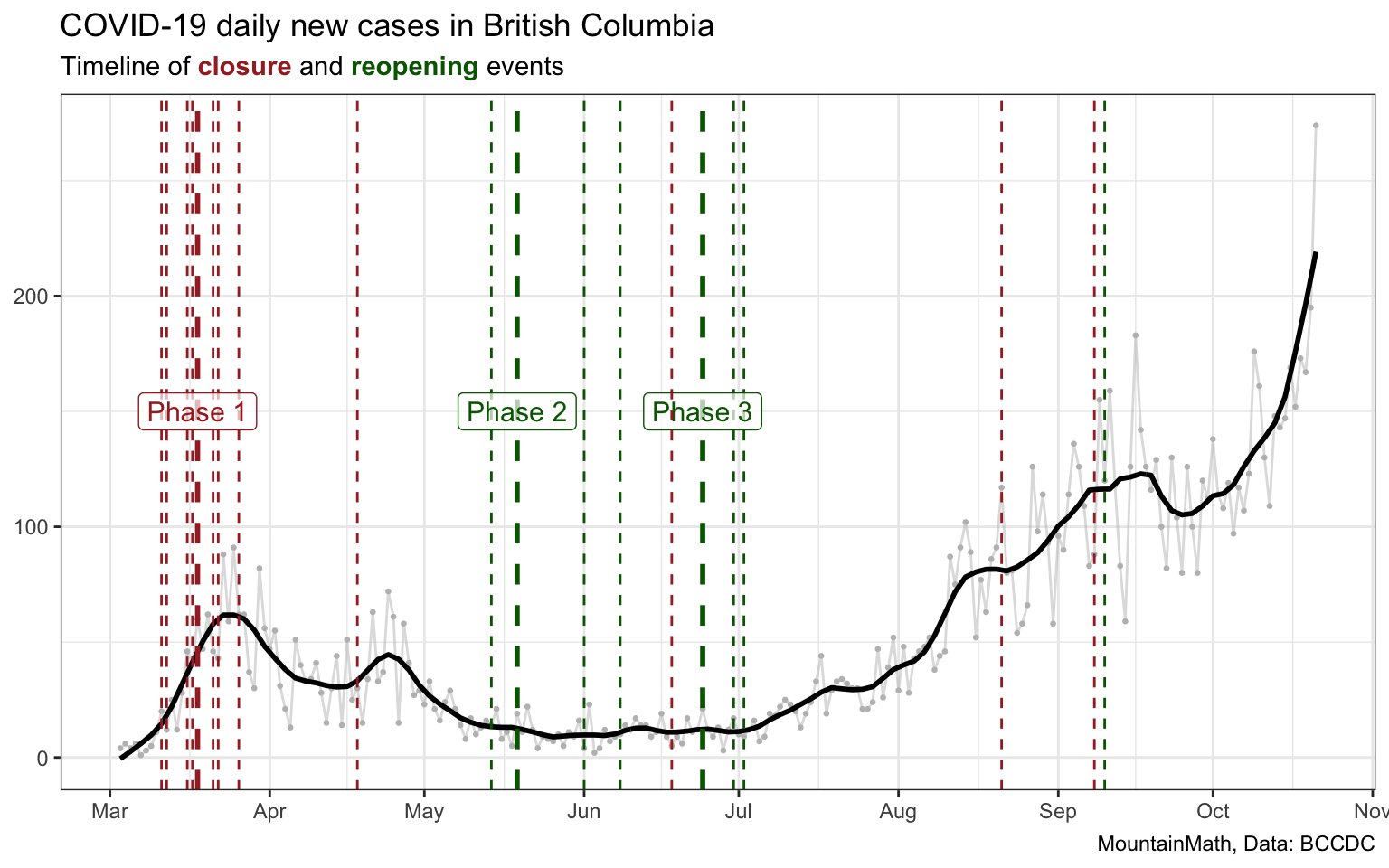

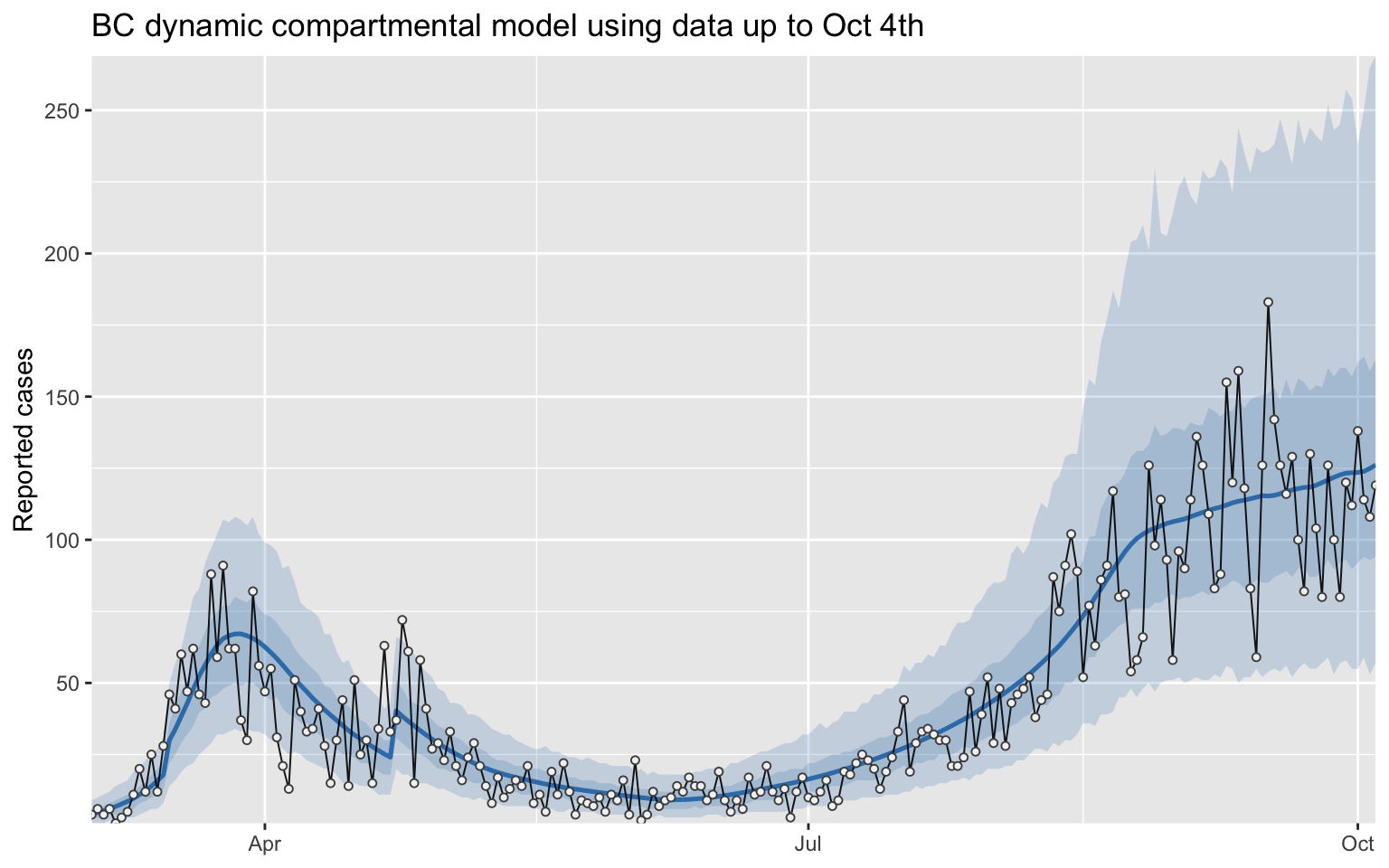

For some context, let’s consider our daily case counts, cleaned up a bit by removing the strong weekly seasonality in the daily counts and smoothing over nearby variations. For better context we added significant events where BC imposed restrictions or loosened restrictions to react to the behaviour of the spread.

The case counts at the beginning of the period aren’t directly comparable to the ones toward the middle and end as we were not testing in the same way, and not testing as much. (Testing data in BC has issues too and is largely uninterpretable at this point, we will leave this for another post.)

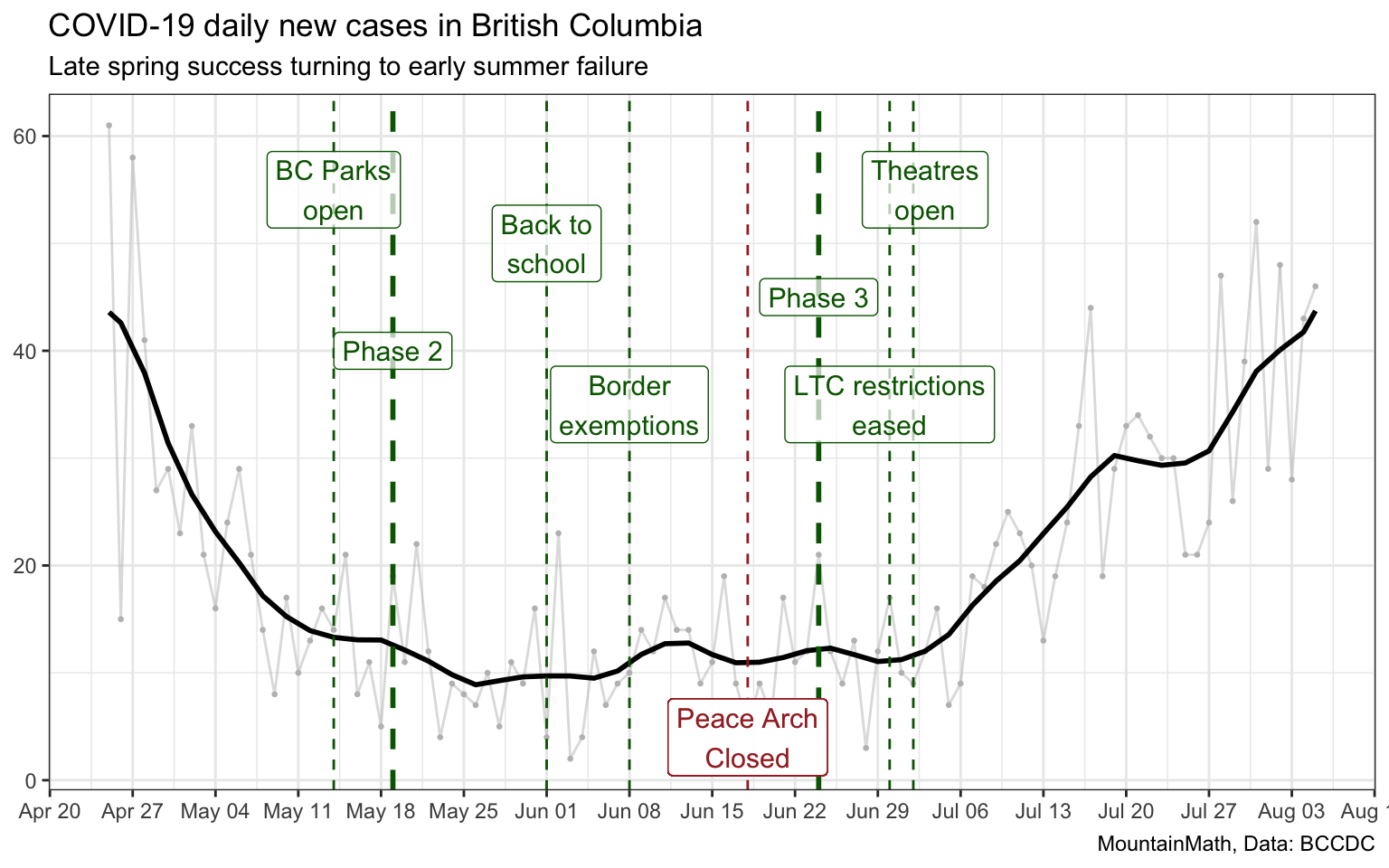

We want to pay particular attention to the period in late spring and early summer, where we dipped into single digit daily new cases, only to let all that progress go to waste and allow the virus to grow again.

Because of the inherent lag between infections and reported cases we expect about a week or two for changes in COVID-19 restrictions to become visible in the data. Going to Phase 2 seems to have resulted in only a modest increase in cases. In contrast, going to Phase 3 has started us on an upward trajectory undoing all the gains our hard work in Phase 1 has gotten us.

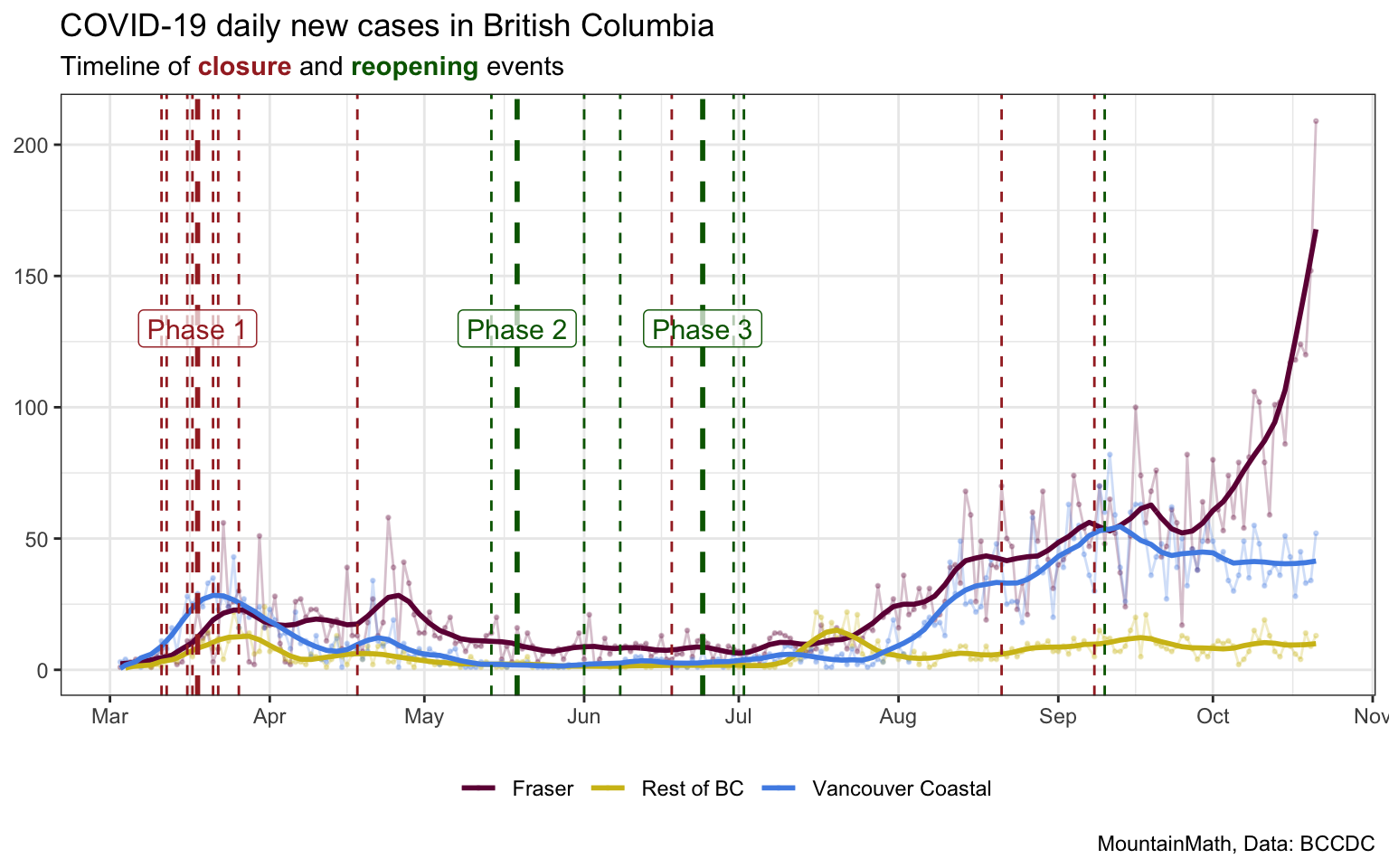

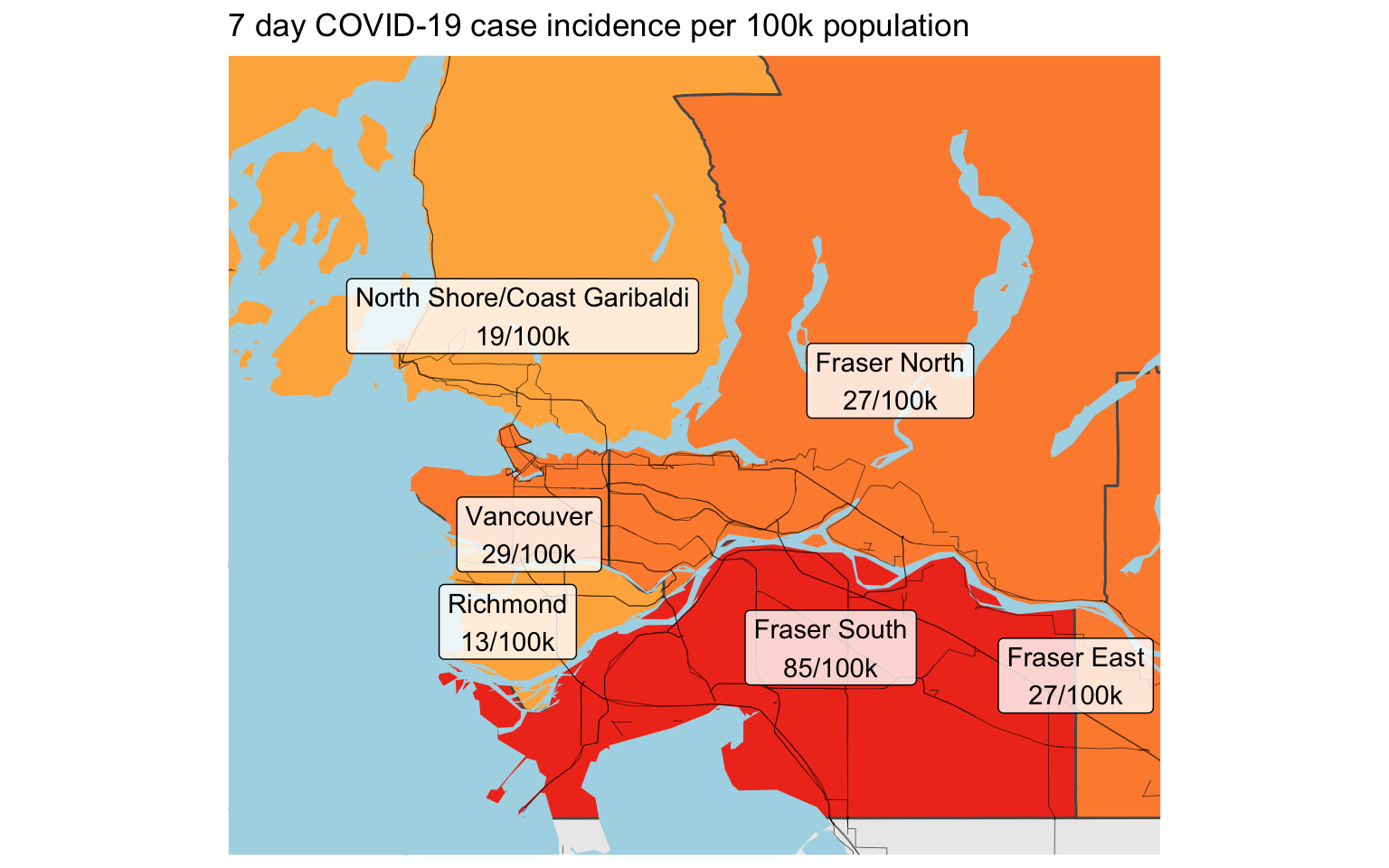

Looking only at overall provincial numbers looses some important aspects of the story. In the short term, COVID-19 spread is a local story. But local spread can quickly jump and take hold in other areas.

Initially Vancouver Coastal may have acted as a seed, the “Kelowna cluster” visible in yellow around July 18 may have served as a catalyst to trigger the subsequent increase in Fraser and Vancouver Coastal. And the rapid increase in Fraser, reporting over 200 cases in a single day yesterday, may well spill back over into the neighbouring health authorities. Unfortunately we don’t have more detailed epidemiological data available to verify these hunches to better understand how the virus spreads to avoid future outbreaks.

Problems

Hand in hand with formulating a goal that’s different from our current “muddling along without blowing through our hospital capacity until we maybe have a vaccine that’s hopefully effective”, we need to understand some of the problems with our response in BC. Those problems aren’t unique to BC, but I strongly believe that they need fixing in order to have an effective response.

BC’s problems can be roughly divided into two parts:

- catching up with the science

- catching up with the data

The second one is squarely in our wheelhouse, so we will talk mostly about that. That does not mean that the first one is less important, it centres around the issue that Canada and BCCDC have been slow in recognizing the role of aerosol spread and non-symptomatic transmissions. This has translated into problematic policy decisions and is also reflected in the inability to grapple with the over-dispersed nature of the virus that (at this point) manifests itself through the combination of aerosol and non-symptomatic spread. While this does deserve a lot more attention, we will save that for a different post.

Catching up with data

We have written about the sorry state of COVID-19 data in Canada before, and things haven’t improved much since. Some provinces and health regions, for example Toronto, have improved the spatial resolution of their data. For example, Toronto is now publishing epidemiologically relevant data, including onset of symptoms date and transmission types, at the local neighbourhood levels. But data gaps abound.

In BC the data situation is pretty much as bad as it has been from day 1. It’s frustrating to watch that the PHO is still presenting grossly outdated data in the press briefings and misrepresents the associated outdated models and summary stats as current, when the conclusions often simply don’t hold any more in our fast-moving pandemic environment.

Out of date data

In a pandemic it’s incredibly important to have timely data to react fast to a changing landscape. We have a lag between infection and onset of symptoms, which often serves as a trigger for a test, that we cannot control. But we have control over everything that happens after. If we can get people to get a test right when they experience symptoms, and get the test result fast, TTI can stay ahead of the virus. Unfortunately, in BC this process is too slow with still around 5 days between onset of symptoms and test result, which means close contacts of the index case may have already lead to secondary infections before TTI even starts.

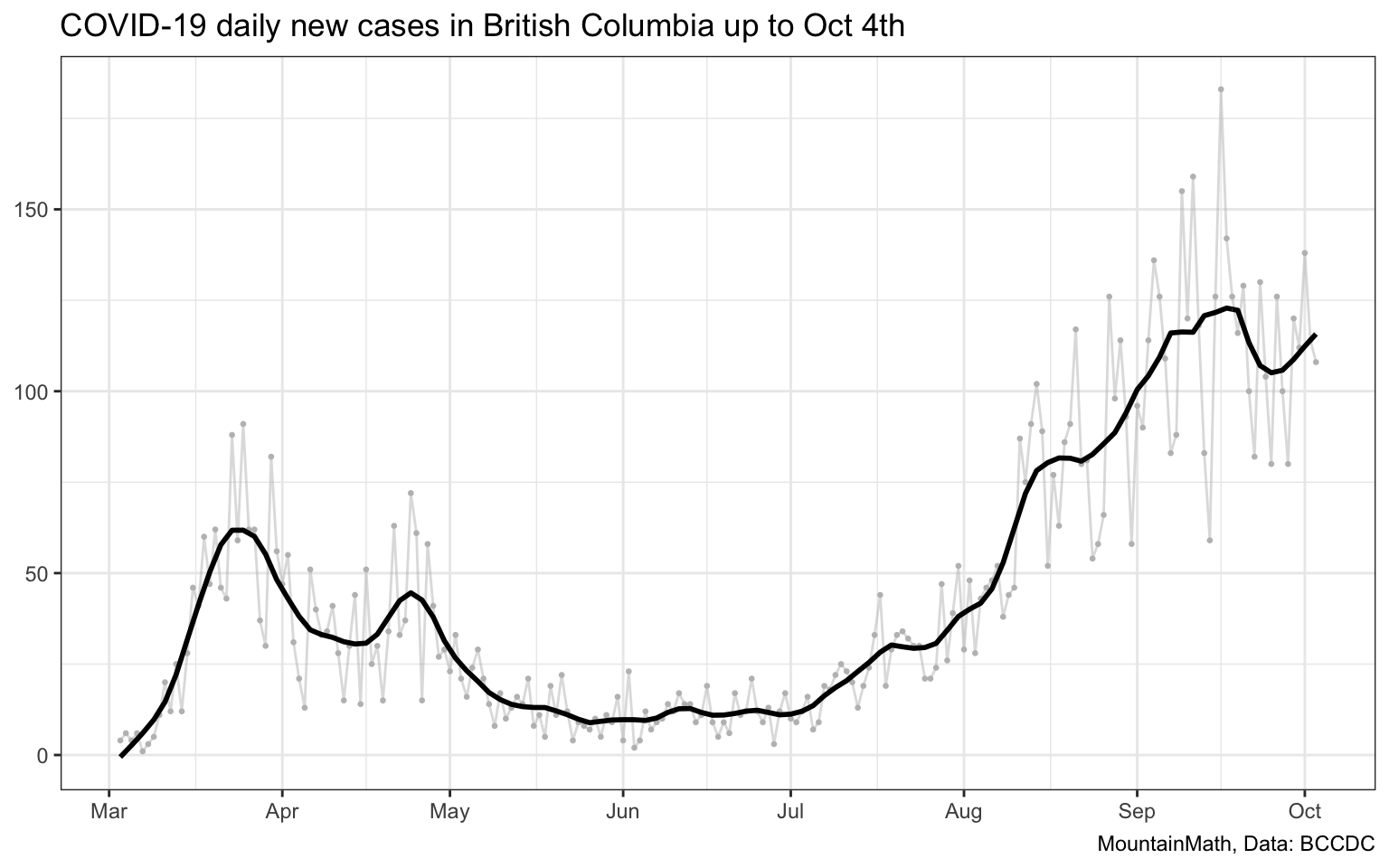

But this is far from being the only issue, we frequently make decisions based on outdated data. Take the example of the last modelling update on October 5, where the PHO was showing off modelling that put BC on a strong downward trend. However, this modelling was old, and already outdated at the time of the press conference. The dip in cases that the model was reflecting had already been undone in the meantime, and BC was on a clear upward trajectory.

This type of misinformation, spread by the chief medial officer no less, is dangerous during a pandemic. Claiming that we are “doing well” while current data does not support that can lead the public to let their guard down at a time when the opposite is required. And this isn’t just a problem of using a different model, had the PHO included the data up to the previous day, Oct 4th in their dynamic compartmental model run, the PHO would have also noted that BC was on an upward trajectory.

Using outdated data to claim that “our growth rate is decreasing” while current data shows the opposite, that’s obviously very problematic. (And not just because it is obvious to anyone watching the video that the PHO mixes up the function with it’s first derivative.) Saying that number of new infections is decreasing (or that the growth rate is negative), when in fact the opposite is true, is sending counter-productive signals to the public.

One might hope that BCCDC has up-to-date internal modelling, and only the modelling presented at the press conference lags for some reason. But it’s preposterous to assume the PHO would have made those statements based on outdated modelling if she knew that up-to-date modelling told a different story.

Lack of spatial resolution

As we have seen when looking at health region geography data, finger geographies matter in understanding short term trends In BC, much of the implementation details on school opening has been downloaded to the school districts. But school boards don’t have timely information on the COVID-19 spread in their district, if at all.

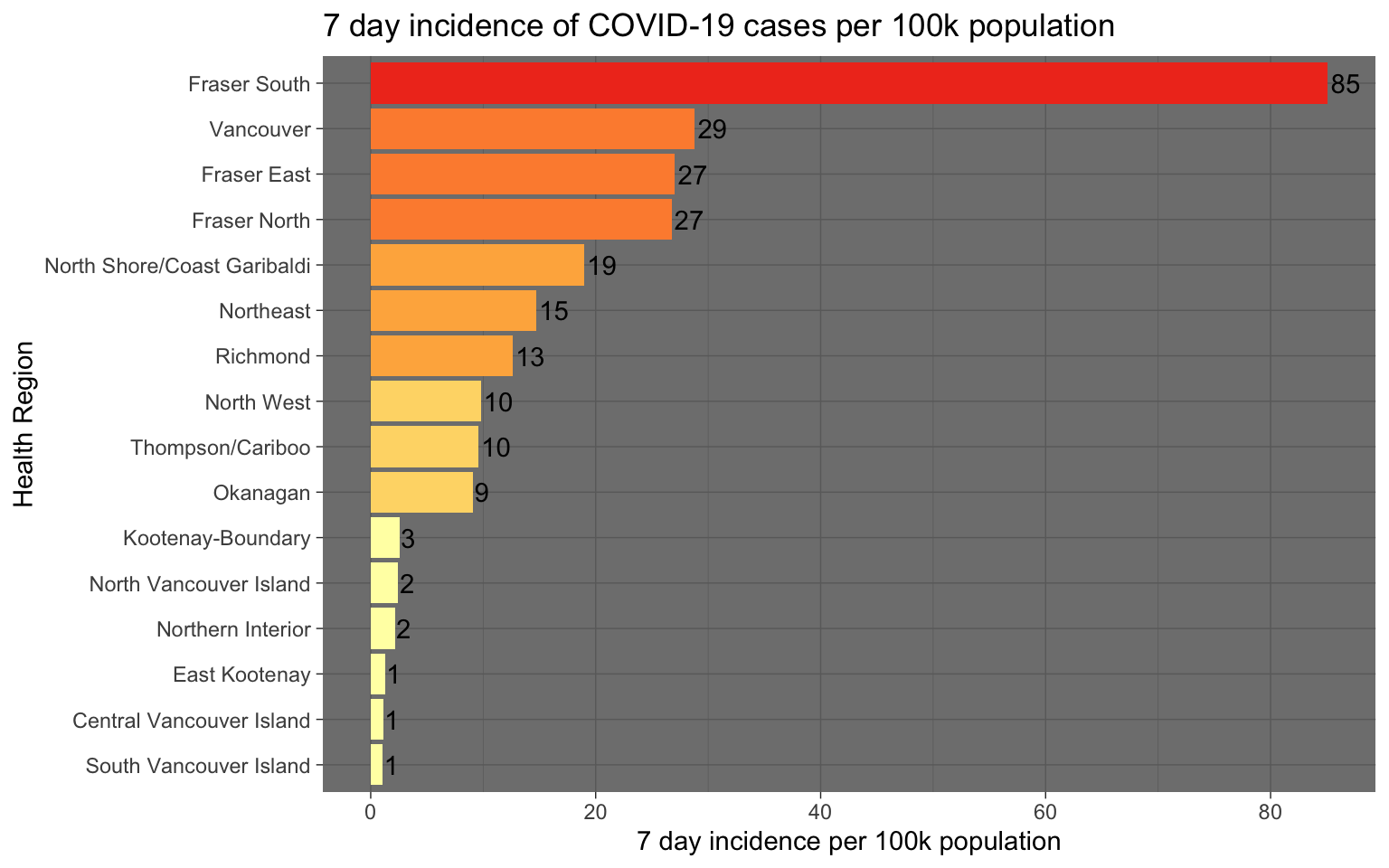

In BC we only have daily data at the Health Authority geography, with weekly updates at the Health Region level. Health region level is only available in image form and needs to be manually transcribed to be useful. Moreover, historical data is not made available and it requires people to scrape the data to establish timelines.

As an example we scraped today’s and last week’s data to compute the 7-day incidence, that is the (cumulative) number of cases over seven days per 100k population, at the health region geography.

Timely finer geography data does not just enable the population to understand the exposure risk in their community and adjust their behaviour accordingly, it also enables a more tailored government response. For example, in regions in Germany where the 7-day incidence exceeds 50, higher level restrictions are triggered. Masks become mandatory in all public spaces and children have to wear masks full-time in school.

Upshot

Data sits at the base of our pandemic response. Without timely and accurate data, we can’t generate timely and accurate information. Without timely and accurate information we can’t mount an effective response. Our data problems are still massive, and they are preventing us from getting timely and accurate information and hinder our response.

Data on its own is not enough, we also need to have a discussion on what our goals should be. We celebrated days with single digit new cases in late spring. We did not worry when case numbers doubled to 20 a day. We did not act when case numbers doubled yet again to 40. When it doubled to 80 a day we strengthened enforcement a little, at 120 a day we imposed restrictions on bars and banquet halls. But when daily cases doubled again to 160 a day we did nothing. There are no clear goals, we are slowly sliding up the ladder of growing cases. Without a clear goal there won’t be a clear strategy.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub in case others find it useful.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2020-10-22 20:06:25 PDT"## Local: master /Users/jens/Google Drive/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [65bd024] 2020-10-05: higher precision to the percentage of people that have experienced homelessness## R version 4.0.2 (2020-06-22)

## Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin17.0 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Catalina 10.15.7

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRblas.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/C/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] ggtext_0.1.0 mountainmathHelpers_0.1.2

## [3] CanCovidData_0.1.4 covidseir_0.0.0.9010

## [5] forcats_0.5.0 stringr_1.4.0

## [7] dplyr_1.0.2 purrr_0.3.4

## [9] readr_1.3.1 tidyr_1.1.2

## [11] tibble_3.0.3 ggplot2_3.3.2

## [13] tidyverse_1.3.0

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] matrixStats_0.57.0 fs_1.4.1 sf_0.9-6

## [4] cansim_0.3.5 lubridate_1.7.9 httr_1.4.2

## [7] rstan_2.21.2 tools_4.0.2 backports_1.1.10

## [10] R6_2.4.1 KernSmooth_2.23-17 DBI_1.1.0

## [13] colorspace_1.4-1 withr_2.3.0 tidyselect_1.1.0

## [16] gridExtra_2.3 prettyunits_1.1.1 processx_3.4.4

## [19] curl_4.3 compiler_4.0.2 git2r_0.27.1

## [22] cli_2.0.2 rvest_0.3.6 xml2_1.3.2

## [25] bookdown_0.19 scales_1.1.1 classInt_0.4-3

## [28] callr_3.4.4 digest_0.6.26 StanHeaders_2.21.0-6

## [31] rmarkdown_2.3 pkgconfig_2.0.3 htmltools_0.5.0

## [34] dbplyr_1.4.4 rlang_0.4.8 readxl_1.3.1

## [37] rstudioapi_0.11 generics_0.0.2 jsonlite_1.7.1

## [40] inline_0.3.16 magrittr_1.5 loo_2.3.1

## [43] Rcpp_1.0.5 munsell_0.5.0 fansi_0.4.1

## [46] lifecycle_0.2.0 stringi_1.5.3 yaml_2.2.1

## [49] pkgbuild_1.1.0 grid_4.0.2 blob_1.2.1

## [52] parallel_4.0.2 crayon_1.3.4 haven_2.3.1

## [55] gridtext_0.1.1 hms_0.5.3 knitr_1.30

## [58] ps_1.4.0 pillar_1.4.6 codetools_0.2-16

## [61] stats4_4.0.2 reprex_0.3.0 glue_1.4.2

## [64] evaluate_0.14 blogdown_0.19 V8_3.2.0

## [67] RcppParallel_5.0.2 modelr_0.1.8 vctrs_0.3.4

## [70] cellranger_1.1.0 gtable_0.3.0 assertthat_0.2.1

## [73] xfun_0.18 broom_0.7.0 e1071_1.7-3

## [76] class_7.3-17 units_0.6-7 ellipsis_0.3.1Reuse

Citation

@misc{covid-19-data-in-bc.2020,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {COVID-19 {Data} in {BC}},

date = {2020-10-22},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-10-22-covid-19-data-in-bc/},

langid = {en}

}