(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

Empty Homes Taxes are back in the news!

In a very short time period, we’ve got Vancouver raising its Empty Homes Tax rate from 1% to 3%, based in part on a report from CMHC about a sharp rise in condos on the rental market, we’ve got Toronto eyeing its own Empty Homes Tax, and now reports suggest that even Ottawa is considering getting in on the game.

We’ve long argued that Empty Homes Taxes are a pretty good tax. Consider it as equivalent to a bump up to property taxes (which cities like Vancouver could really use!) paired with a principal residency exemption, kind of like BC home owner’s grant, but also applicable to property owners who rent out their properties on a long-term basis, hence providing incentive to keep housing occupied.

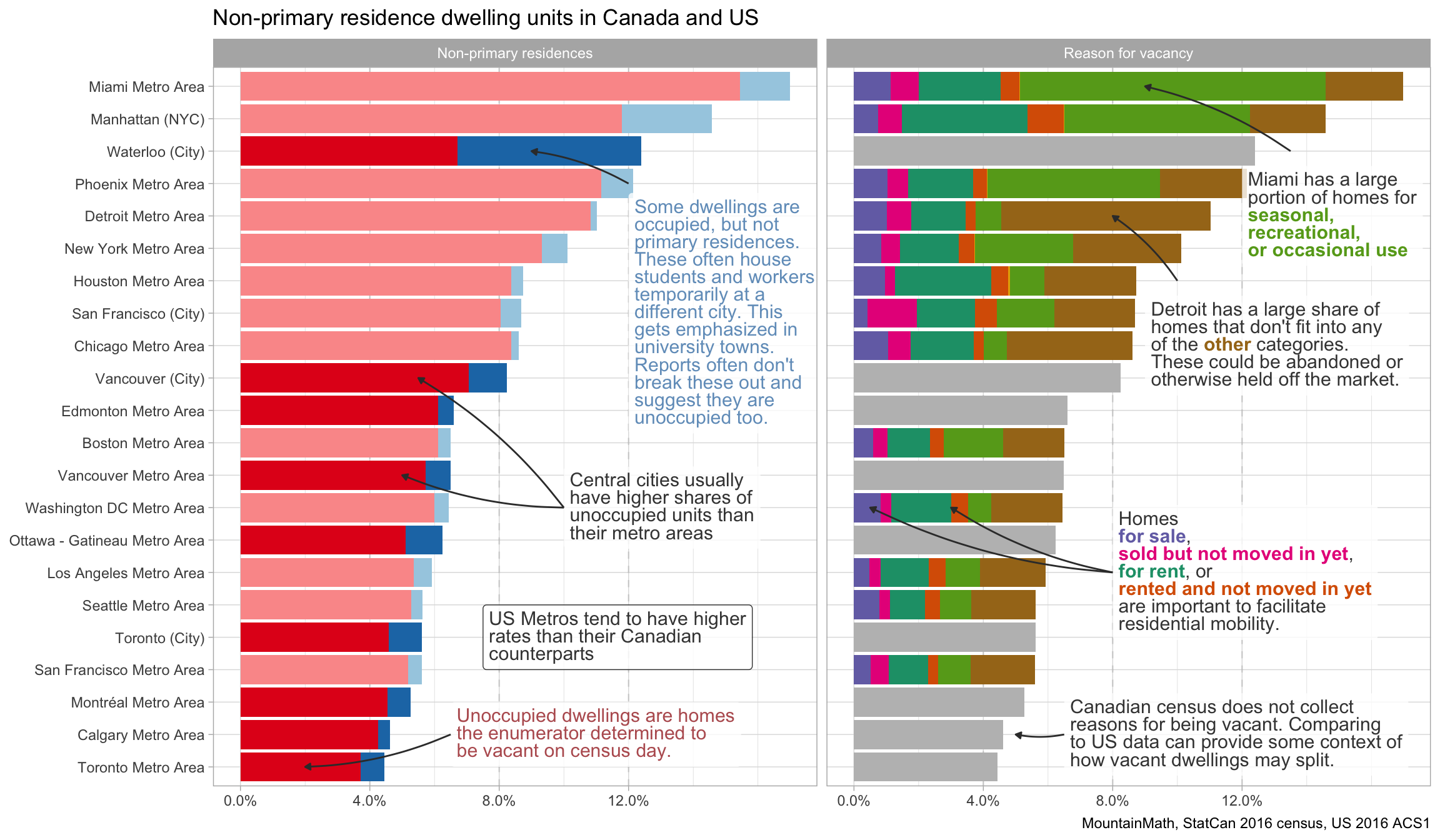

The incentive is real. But we have questions about whether Empty Homes Taxes are being oversold as solutions to the broader housing crises facing Metro Vancouver, Toronto, and Ottawa. To start with, as we’ve demonstrated previously, none of these metro areas rank particularly high in North America in terms of vacant housing stock on census day. Indeed, all Canadian cities appear to be on the low end, implying relatively few of the abandoned homes and vacation pied-a-terres that seem to push up vacancies in many US cities.

Vancouver and Ottawa appear high for Canada, but somewhere between low and middle-of-the-road for North America as a whole. Toronto is definitely on the low end. Of note, a scan of the data for the US, which includes reason for vacancy, suggests that regular housing processes (dwellings up for sale or rent, awaiting new residents; dwellings caught in temporary legal limbo after the death of an owner, etc.) account for a substantial portion of vacant homes overall. For metros at the high end of vacancies, these numbers are boosted by abandoned homes and/or pied-a-terre vacation homes. This suggests that abandoned homes and pied-a-terres just aren’t that common in Canada.

With some caveats, we can test this by looking at Vancouver’s Empty Homes Tax and BC’s Speculation & Vacancy Tax data. Most homes that appear as if they might be empty qualify for exemptions from these taxes, reflecting regular housing processes. After exemptions, there just don’t seem to be very many empty dwellings left. In the most recent Vancouver EHT data, declared vacancies range by neighbourhood from 0.08% (in Sunset & Grandview Woodlands) to 1.26% in the West End, roughly matching the City of Vancouver’s 0.7% of properties non-exempt from the tax in the provincial SVT data (excepting out “Satellite Families”, which would bump the figure to 1%).

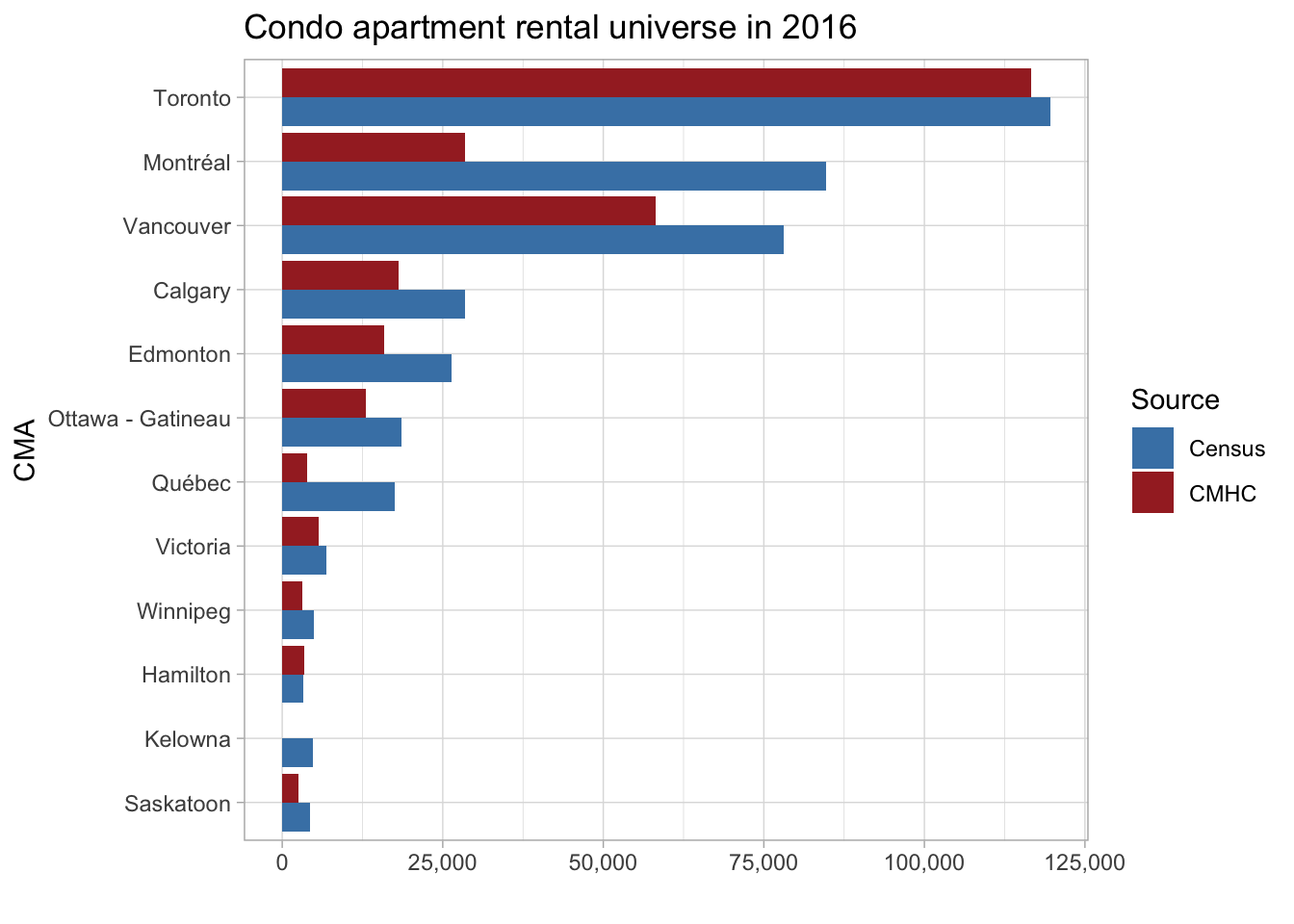

Of course, taxes may be bringing dwellings back into the rental market that weren’t there in 2016, meaning our EHT and SVT data might be reflecting big declines in empty units. What about that CMHC study showing a bump of condos being rented out after the Empty Homes Tax was imposed? Well, funny story… first it’s important to know that the study is based on condo managers reporting from their Form K, which are meant to be filed when condo units are rented out, but in the past have been largely inconsequential. Indeed, in previous work we have highlighted that the CMHC estimate of rented condos in Metro Vancouver differs significantly with census estimates.

Here it’s notable that the first year of the EHT’s existence did not see a great many condos added to the rental market. But after the Speculation and Vacancy Tax came into place, the number of condos being rented out seemed to grow quite a bit. Was this a real change, perhaps because the added taxes became higher? Or did this represent a reporting change? Due to a variety of policy changes (including SVT), suddenly failure to file Form K has more teeth. As a result, it’s likely the reporting compliance for From K has gone up significantly. In other words, we’re not actually certain that a slew of condo units recently came onto the rental market. It may be, instead, that a slew of condo units already on the rental market were suddenly reported correctly. Overall, it is hard to get robust estimates of how many units have entered the market in response to the tax, but there’s no doubt some have. Looking at City of Vancouver data on homes that are either exempt or pay the tax, and cross-referencing this with the Ecotagious study estimating vacancy by electricity usage, we can arrive at a very rough estimate of the number of homes returned to the market being roughly double the number of homes that end up paying the tax. Which is a sizable achievement.

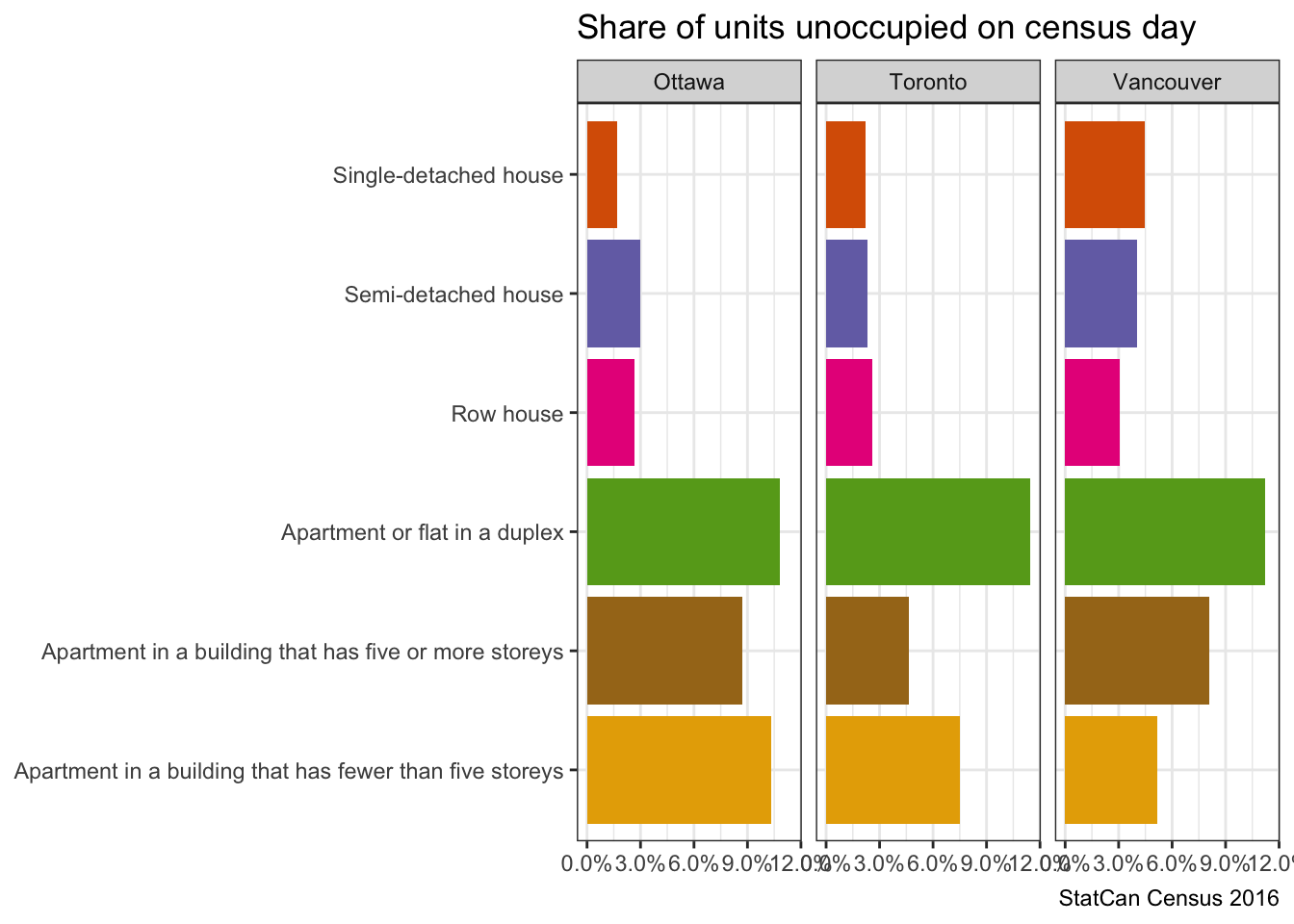

So what should Toronto and Ottawa expect from an empty homes tax? We have previously used City of Vancouver data to give fairly accurate projections for the Speculation and Vacancy Tax, and we can apply the same method to Toronto and Ottawa at the city level. The estimate is quite crude, it simply scales the units “unoccupied” on census day to match the City of Vancouver Empty Homes Tax numbers. So let’s take a quick look at what kind of dwelling registered as “unoccupied” in the Census.

While there is some variation across the regions, the duplex category, which generally captures houses with basement suites, comes out universally with the highest share of unoccupied homes. We have written about this at length before and it should not be surprising given the flexible nature of secondary suites that they are used flexibly, which frequently means that they aren’t rented out. Of course, these suites also aren’t taxed as empty, since they’re considered part of one residential property and can so easily be reabsorbed into the main dwelling. The high prevalence of basement suites in Vancouver is a big part of what drives up its vacancy rate in the census.

Taking account differences in housing stock we can apply a crude formula from the City of Vancouver Empty Homes Tax experience, assuming exemptions are structured similarly. Accordingly we can project that an Empty Homes Tax would capture around 2,000 units in Ottawa and 6,000 in Toronto. Roughly twice that number might be induced to re-enter the rental market in each city.

So should Toronto consider an Empty Homes Tax of its own? Relative to the size of Toronto’s housing market, we probably shouldn’t expect an Empty Homes Tax to a) find very many empty homes, or b) create much new revenue. We’re likely looking at shifting over no more than a single percentage point of units into the market. But adding any new units to the market is good. And we like Empty Homes Taxes overall. Just ensure expectations are set accordingly!

What about Ottawa? Similar wisdom pertains. Set expectations accordingly! At the same time, Ottawa is instructive to consider insofar as it’s the centre of government for Canada. We actually kind of expect a certain number of properties will be empty a substantial portion of the year. Why? Well, Members of Parliament and Senators are both expected to represent other parts of the country in Ottawa. In other words, they’re expected to split their time between Ottawa and elsewhere. Indeed, Senators are still required to own at least $4,000 worth of real property in the province they represent, though there’s currently a bill to repeal that requirement (property requirements for MPs were abolished with the 1920 Dominion Elections Act). Again, not to say an Empty Homes Tax is a bad idea for Ottawa, and why not tax politicians a bit more? But Ottawa is also uniquely well positioned to demonstrate why some people, including - but not limited to - MPs and Senators, maintain some form of residence in multiple places. And Empty Homes Taxes necessarily tend to hit hardest for anyone who finds it difficult to choose just one.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt for their own purposes.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{what-to-expect-from-an-empty-homes-tax.2020,

author = {Lauster, Nathan and {von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {What to {Expect} from an {Empty} {Homes} {Tax}},

date = {2020-12-07},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2020-12-07-what-to-expect-from-an-empty-homes-tax/},

langid = {en}

}