(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

The “real estate has swallowed Vancouver’s economy” zombie is back, with wild claims by a City Councillor that

“If you look at the long-form census data going back to 1986 every 5 years, […] we went from selling logs to selling real estate […], major shift from resource extraction to real estate property development and construction as the primary driver in the local economy.”

Here we want to try and put the zombie out of our misery (again!), but also use this moment to ask some interesting questions about Vancouver history and what we can get from the long-form census. Mostly what we get from the census, of course, is what people list as their jobs. We can use this to ask a series of questions, including:

Just how many people work in the real estate industry in Vancouver? Is it growing?

What about finance? Are we turning into a “Global City”?

Have these activities truly replaced selling logs (or other extractive industries) as the basis for Vancouver’s economy in terms of jobs?

How about manufacturing? Didn’t we used to make things?

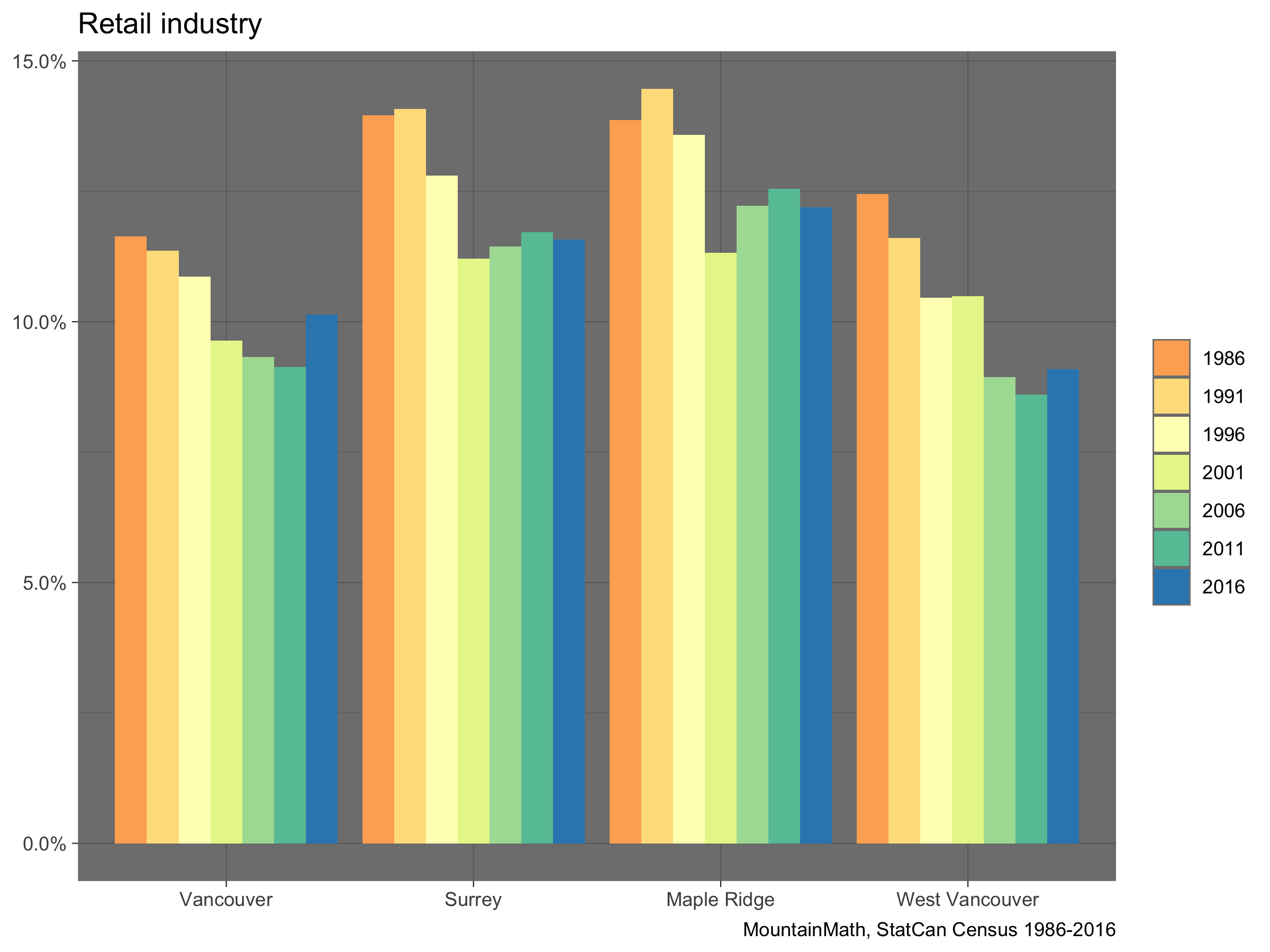

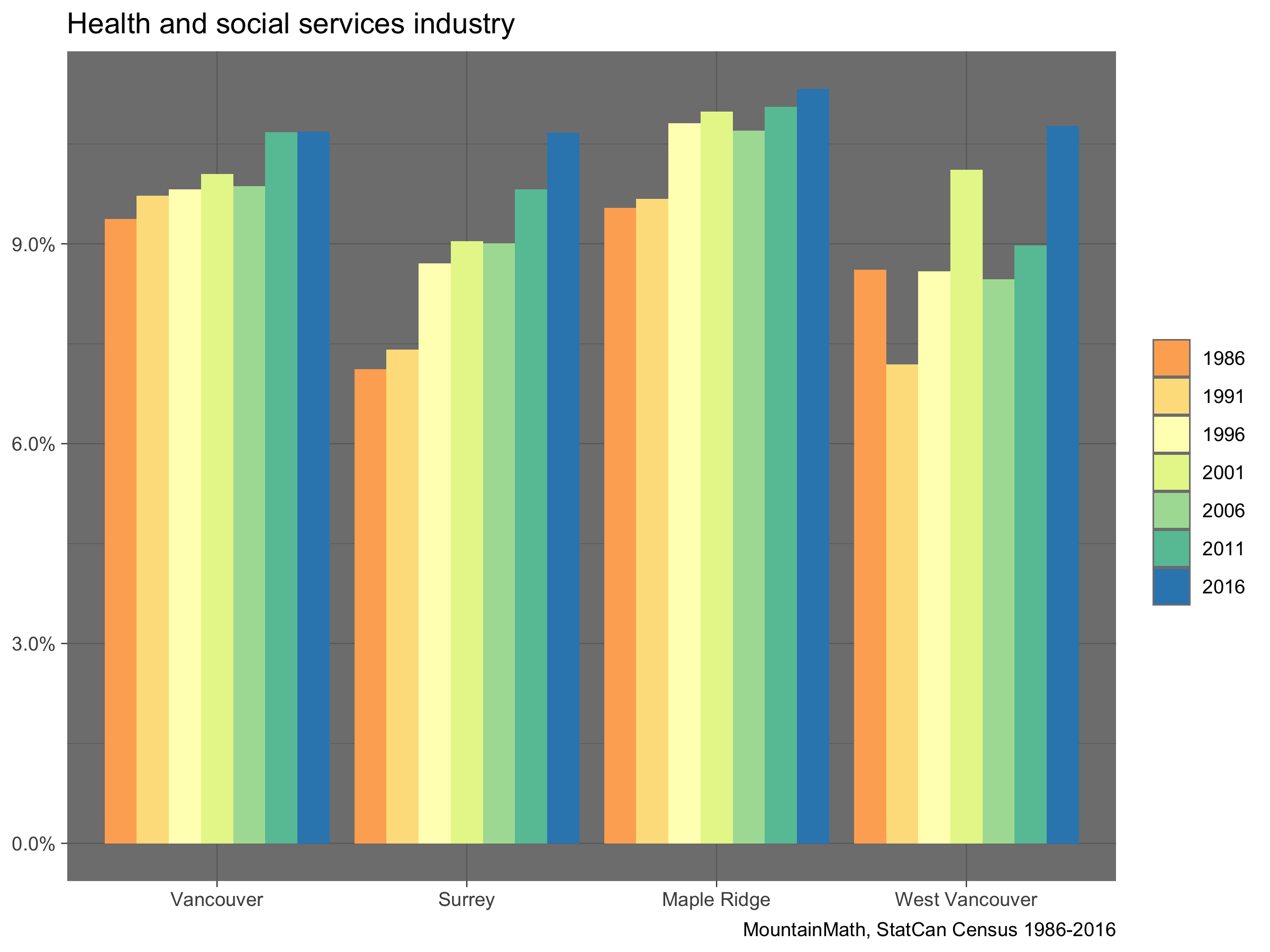

What about retail? Or health care and social services? Are we mostly relegated to being a regional commerce and service centre for BC?

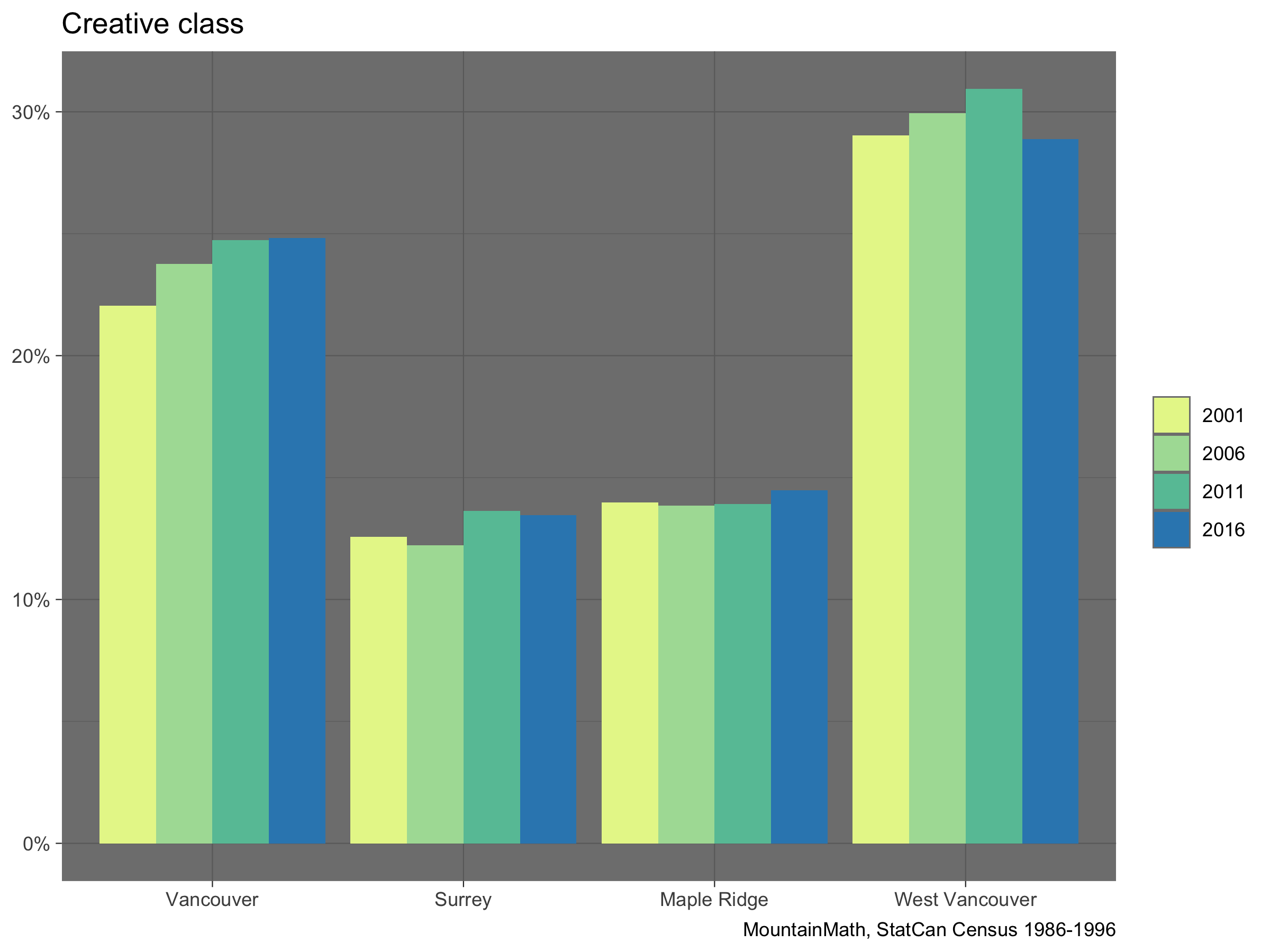

What about the “creative class”? Is it growing? And what even is that?

Before we get to that we should mention that there is another way to look at industries, instead of using the census to look at people and their jobs, we can look at money (GDP). There is no GDP data for small area units like municipalities within a CMA, but CMA level (and higher geographies) GDP data is available from StatCan and we have written extensively about the size of the Real Estate Industry in terms of GDP before.

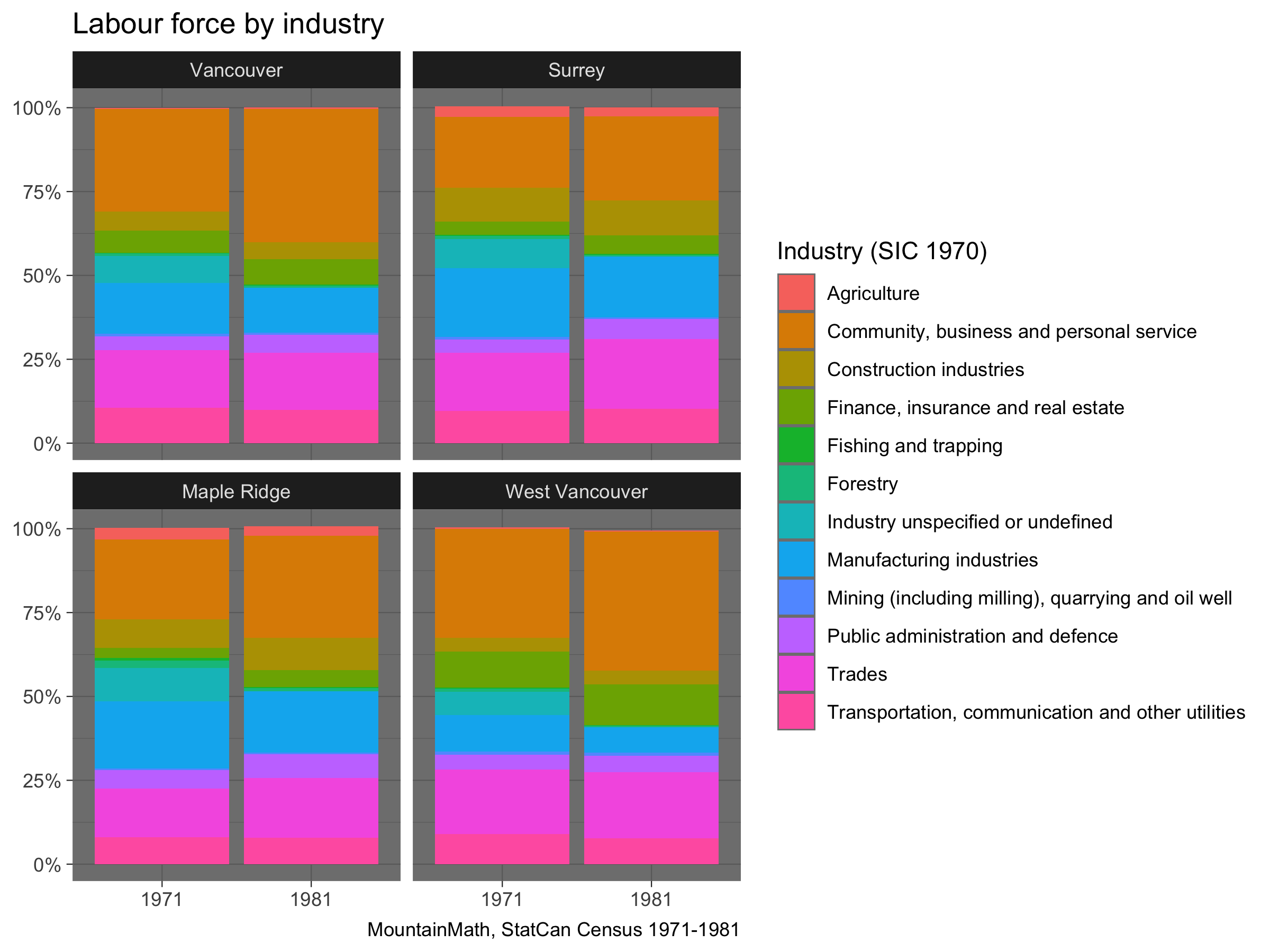

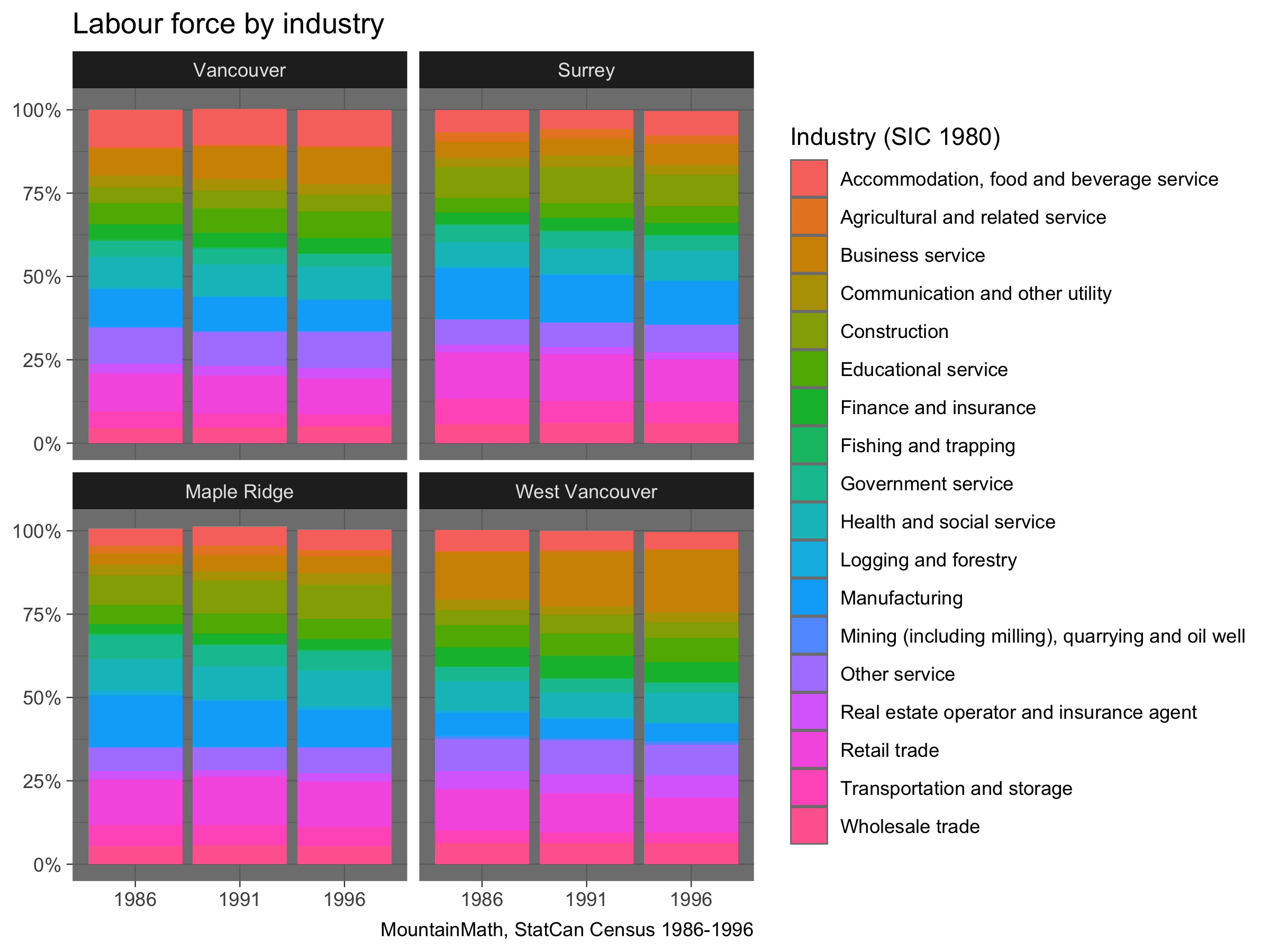

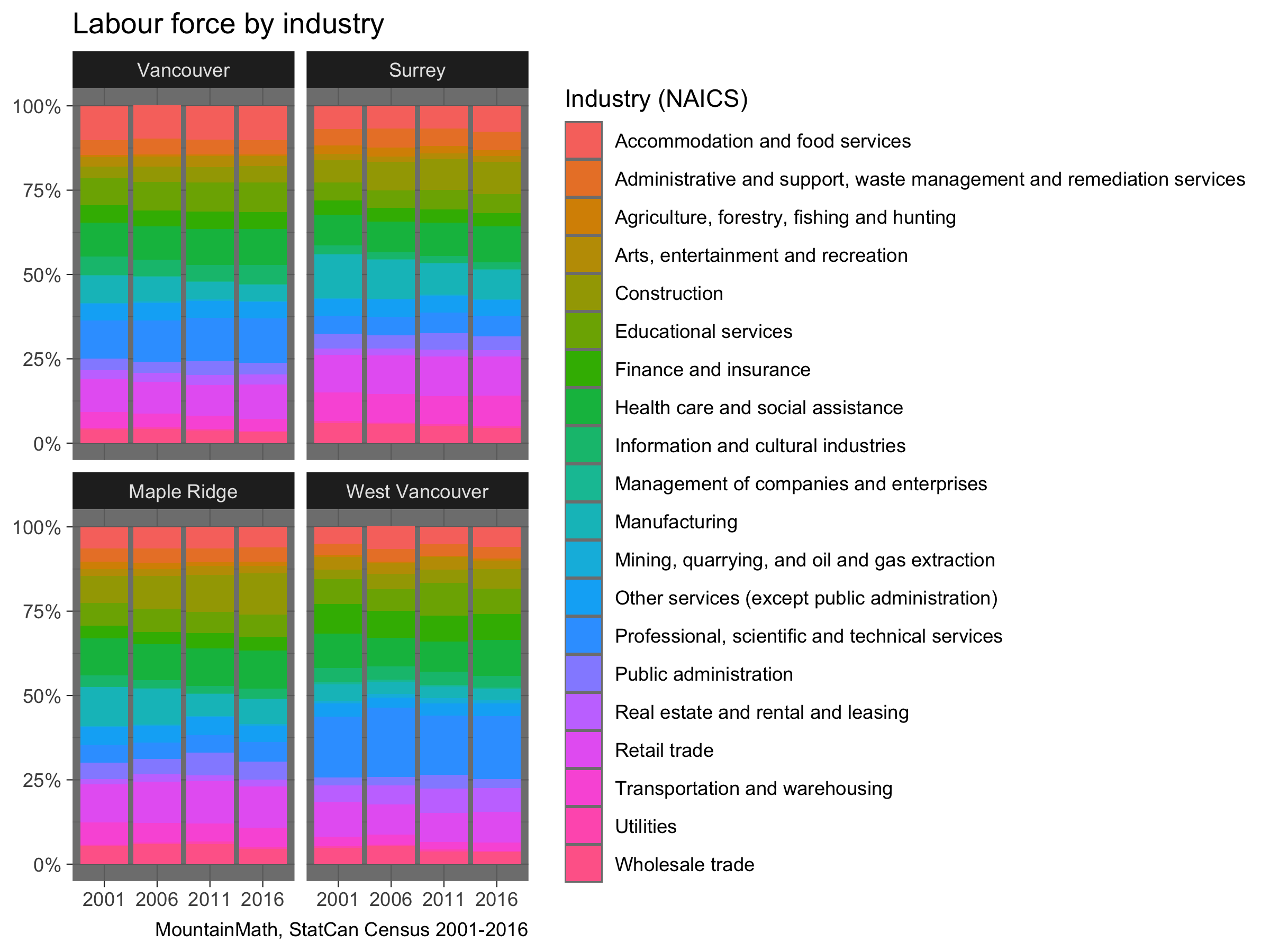

But here, for jobs, we got some nice longitudinal data to answer these questions, looking at the Industrial classification of our workforce via Census running back to 1971! The biggest trick is making the industrial categories speak to our questions above and to one another across time. There were three major shifts in categories, going from SIC 1970 to SIC 1980 and finally to NAICS (and various refinements of NAICS, which are relatively minor). We can also break out interesting municipalities within Metro Vancouver. Here we’ll explore the City of Vancouver, Surrey (its largest suburb), Maple Ridge (an outlying working class suburb), and West Vancouver (its wealthiest suburb), providing some sense of geographic variation in the structuring of the labour force through time. Some of those city geographies changed through our timeframe, for consistency we will use 2016 census subdivision boundaries throughout.

Let’s start with an overview of our categories for each of the periods covering the major categories.

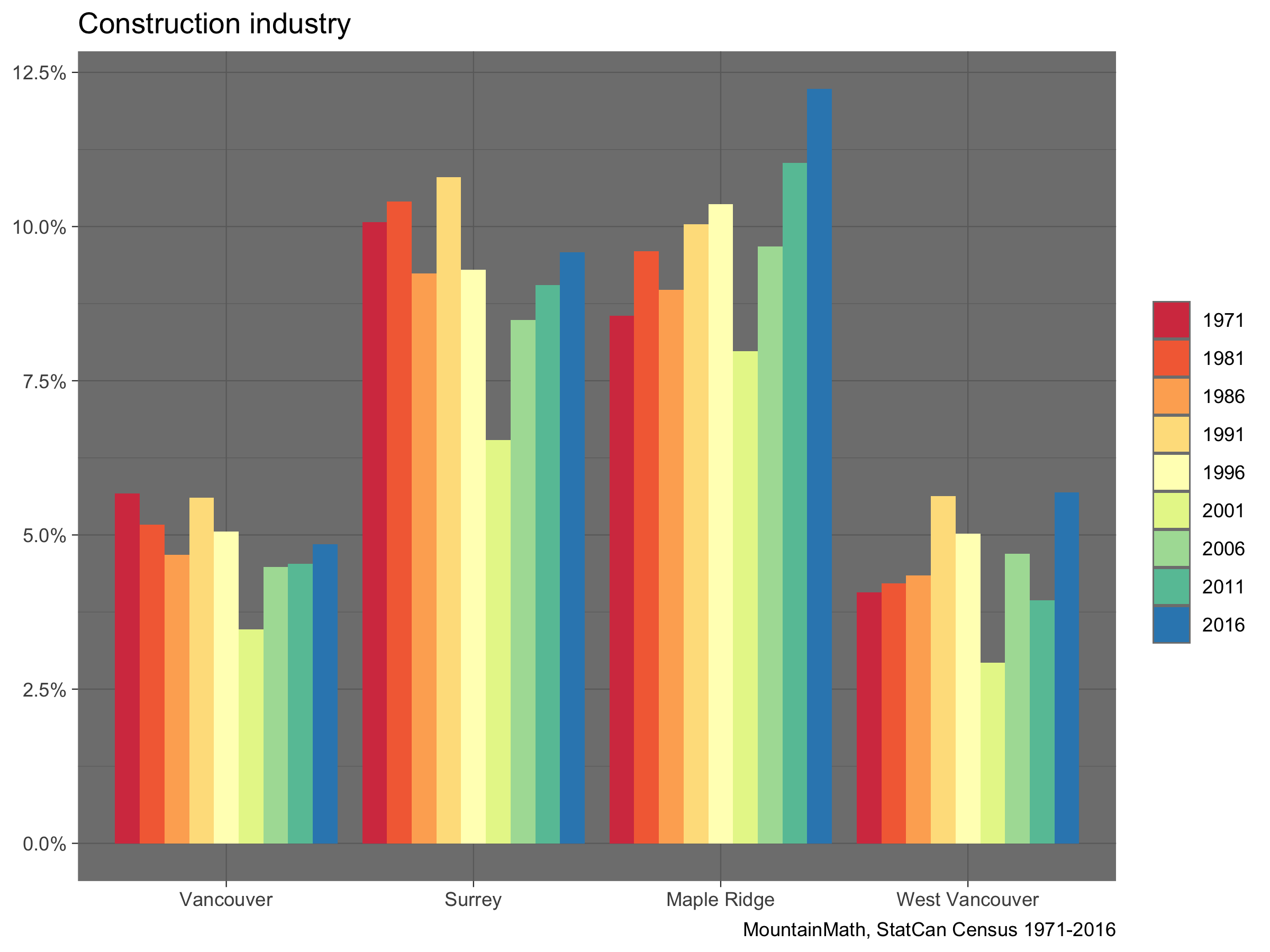

Let’s start to tackle the real estate question by examining two general groups: those engaged in building (construction), and those engaged in sales & leasing (real estate agents, managers, etc.). In 1971-1981, we get categories for “Construction Industries” and “Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate” so we can’t entirely pull out real estate. But this is a start. By 1986-1996, we still get “Construction” separated, but we pull “Real Estate operator and insurance agent” apart from “Finance and insurance.” From 2001-2016, we get consistent categories with “Construction” separated from “Real estate and rental and leasing.”

So let’s start with construction work.

Construction work looks either stable or cyclical, with low points in 1986 and 2001 rising to high points in 1981, 1991, and 2016. Of note, only in the outlying suburb of Maple Ridge do we see our most recent census year (2016) eclipsing previous high points in terms of construction labour force. This reflects a dearth in building through recent decades across much Metro Vancouver, leaving us with our present housing deficit. We’re only now approaching the levels of construction that were prominent in past cyclical peaks. In general, we can think of construction work as varying cyclically and geographically, but occupying about 5%-10% of the workforce.

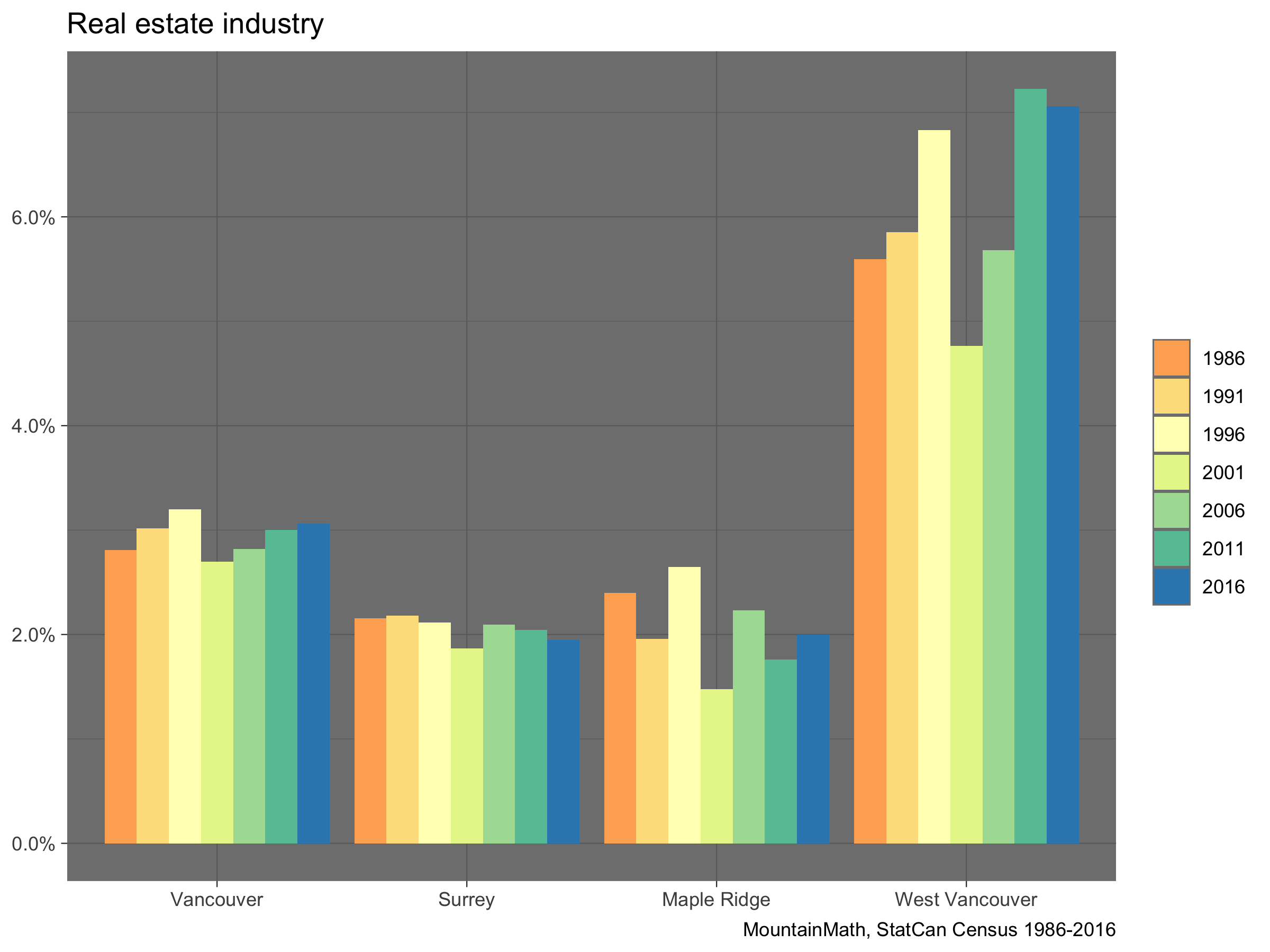

What about the rest of the Real Estate Industry? All those realtors and property managers?

These folks are not as big a part of the workforce as the construction industry, occupying about 2%-3% of the workforce in most municipalities. This appears to be remarkably stable through the decades. But there’s one big exception, and that’s in West Vancouver. The metro’s ritziest suburb is the only one with more people engaged in the real estate industry than in the construction industry, with the former reaching up to 7% of the workforce.

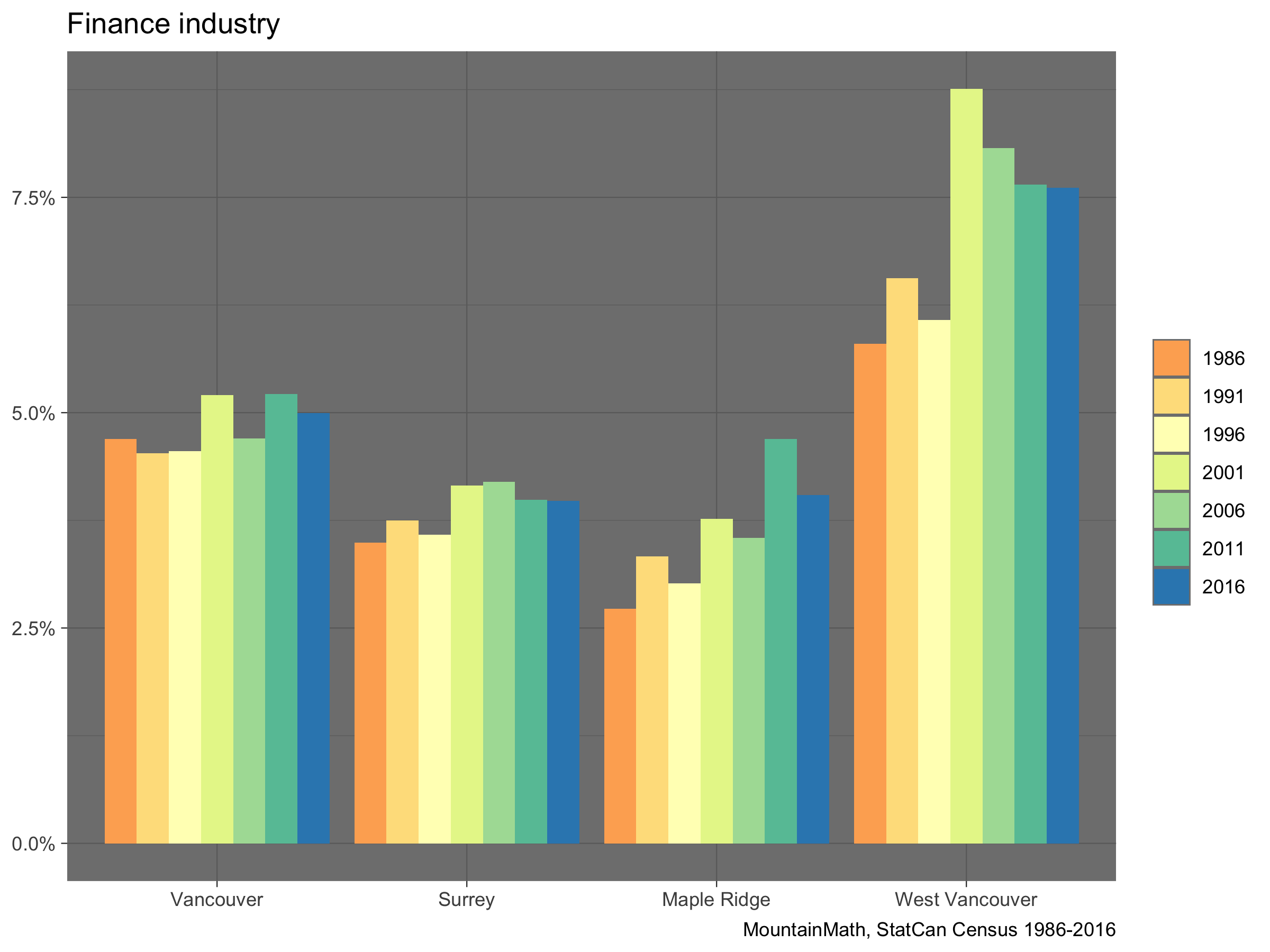

What about Finance? This is often grouped in with Real Estate, but extends more broadly into banking. As we recall from above, Finance is mixed up with Insurance and Real Estate in 1971-1981, but separated into “Finance and Insurance” from 1986 onward. By some definitions, a rise in Financial occupations and related services helps differentiate the world’s “Global Cities” from the rest. Does Vancouver look like an emerging Global City? Let’s take a look…

If we’re a rising Global City, we appear to be getting there very slowly. Indeed, there’s not much change in Finance in the City of Vancouver proper, with a bit more evidence of a rise in the suburbs. Geographically, Finance generally tracks with Real Estate, occupying the most people in West Vancouver. But the peak Finance year there was in 2001, when Real Estate was at its nadir.

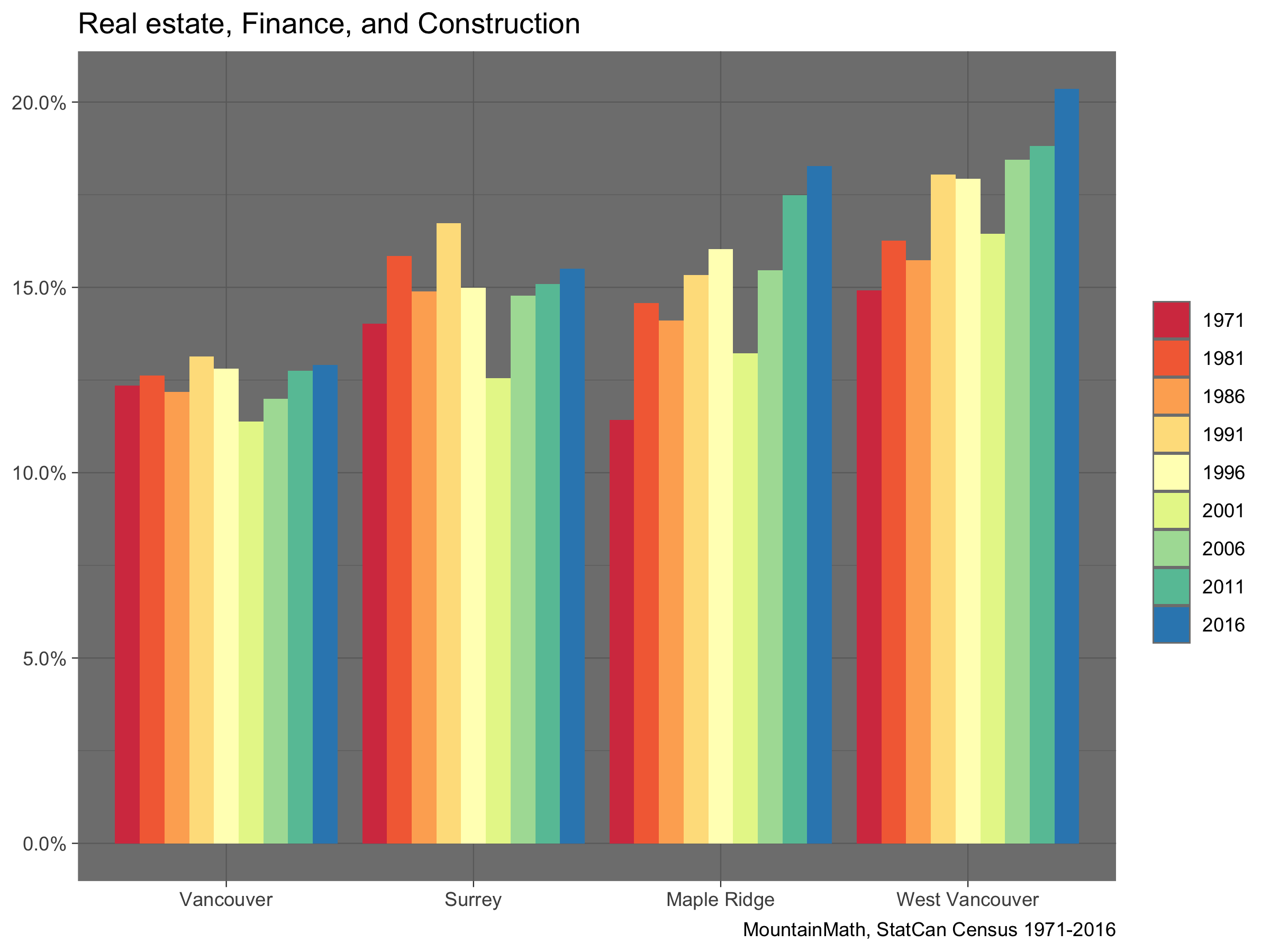

We can combine Finance back with Real Estate and Construction to get perhaps the most comprehensive look at what’s sometimes termed FIRE (Finance Insurance Real Estate) industries. This allows us to go back to our full time-line, from 1971-2016, though we should still be wary of changing definitions through the era.

Overall, we get the sense that even this widest possible categorization of the Real Estate related sector generally provides around 15% of our municipal jobs. Fewer in the City of Vancouver and more in West Vancouver. Vancouver and Surrey show a fairly stable share of jobs in these sectors, Maple Ridge and West Vancouver show an increasing trend. The reason for the variation is diverse, Surrey and Maple Ridge have more construction workers, West Vancouver is heavier in Finance.

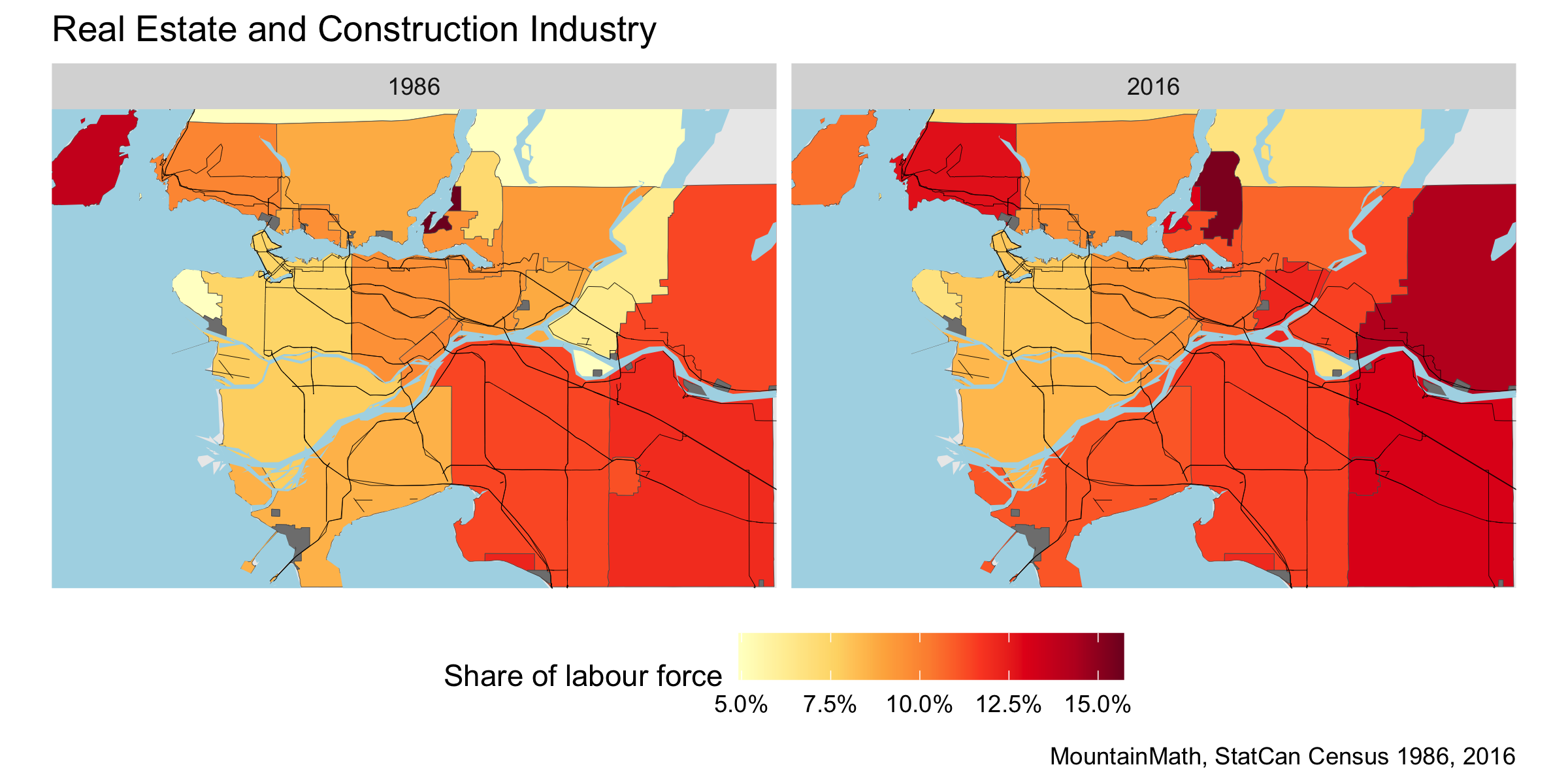

Just to send the zombie home, let’s put this on a map. Here’s the full geographic distribution of Real Estate and Construction as a proportion of the labour force in each municipality. We start the map in 1986, where the quote above begins (and where many critics trace Vancouver’s turn toward real estate as arising after Expo 86). So let’s see how is started and how it’s going.

Overall the picture is… not much change. Definitely not in the City of Vancouver. Maple Ridge got more construction workers and West Vancouver got more high-end realtors. The tiny communities of Belcarra and Anmore traded places in seeing slightly higher proportions in the sector. But nowhere do we see real estate and construction as dominant. For a fully interactive map, head over here.

Huh. So did the quote above get it backward? Did we actually go from selling real estate to selling logs?

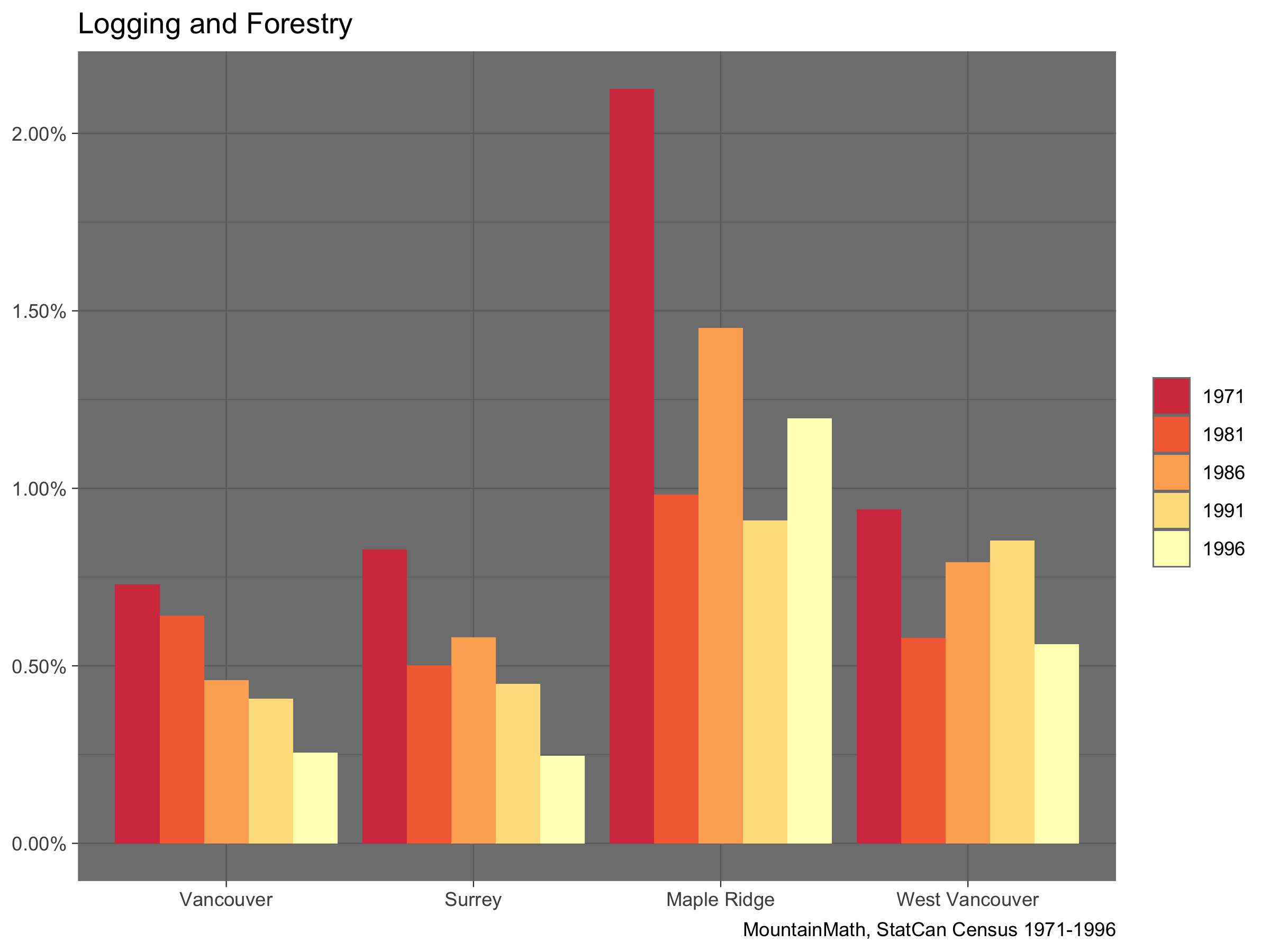

As it turns out, logging and forestry have been a very small part of Vancouver’s labour force for a long time. Indeed, in newer years this category is so small it gets lumped in with agriculture. In 1970, back when Maple Ridge remained at its most remote, it still only recorded just over 2% of its work force in the forestry industry.

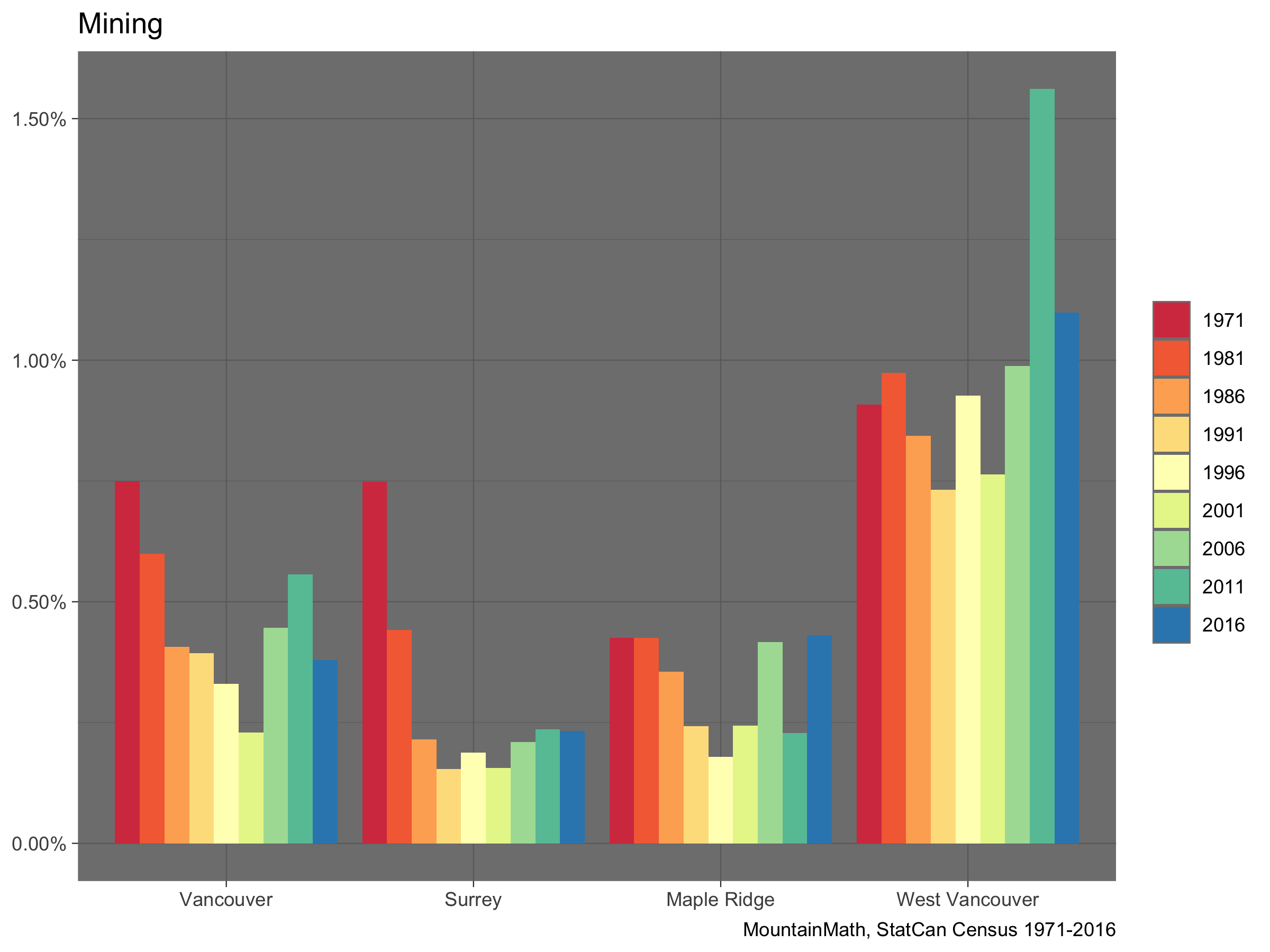

But maybe we’re still extracting! What about mining? Mining makes up a similarly small portion of the labour market, and the consistent categorization makes for an easier way to track this through to the present.

Somewhat strikingly, the biggest proportion of the population engaged in mining is in West Vancouver, reaching all the way up to 1.5% in 2011. Are these rough-and-ready miners, back from working their tunnels? No. These are mostly mining executives, living in Vancouver’s swankiest suburb.

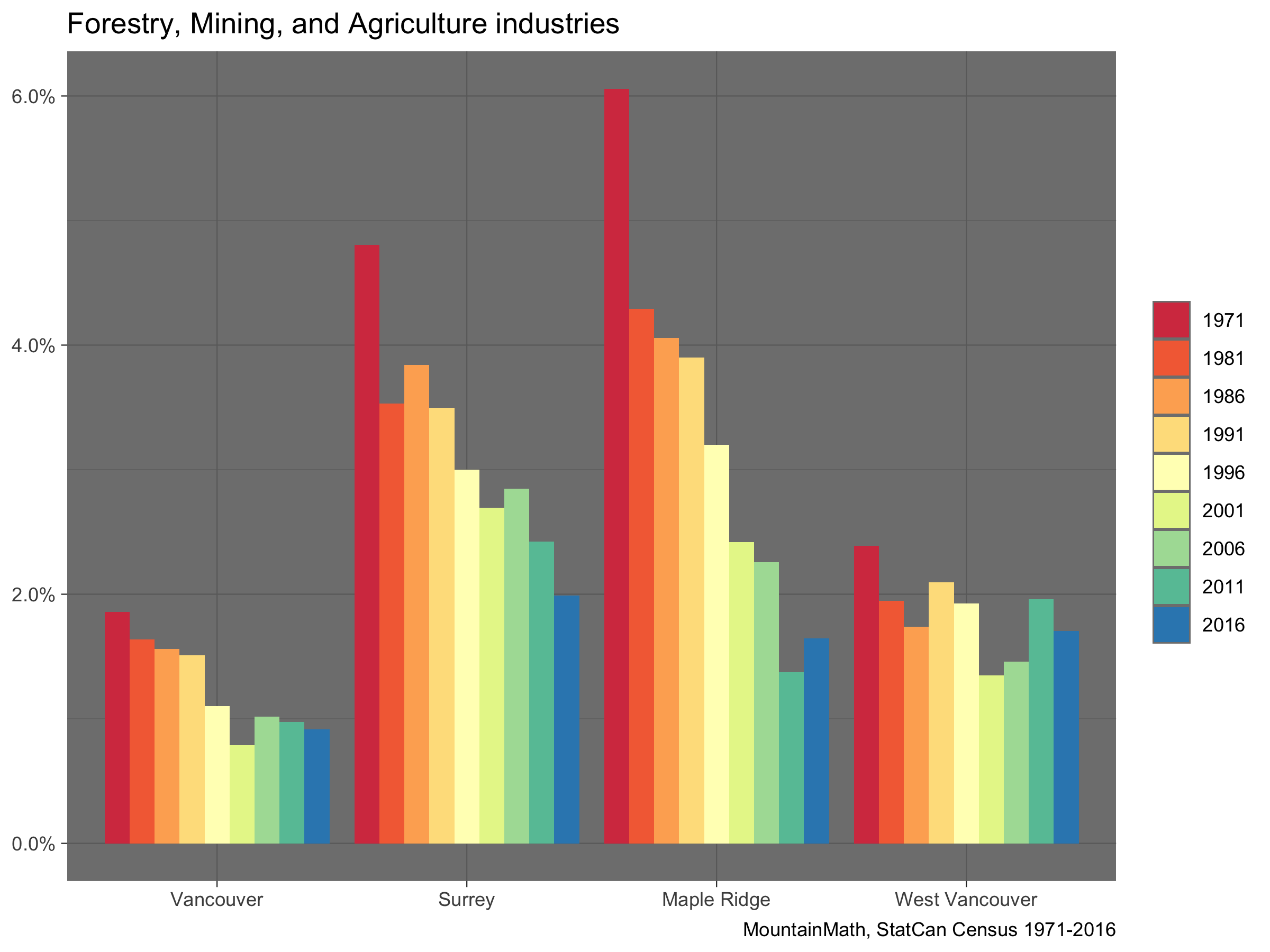

We can combine the above two industries with agriculture to get a fairly consistent picture of the combined categories through time, tracking SIC Divisions A, C, and D and NAICS 11 and 21. Together these speak to the “Staples” of the Canadian economy insofar as the country’s history has been linked to international trade. These industries have always been exceedingly small in Vancouver proper. But Surrey and Maple Ridge have seen marked declines as they’ve gradually shifted from more rural primary sites of timber and agriculture to more integrated positions as metropolitan suburbs. That said, even if the workforce remains small, the Agricultural Land Reserve insures agriculture continues to be a defining feature of the metropolitan landscape.

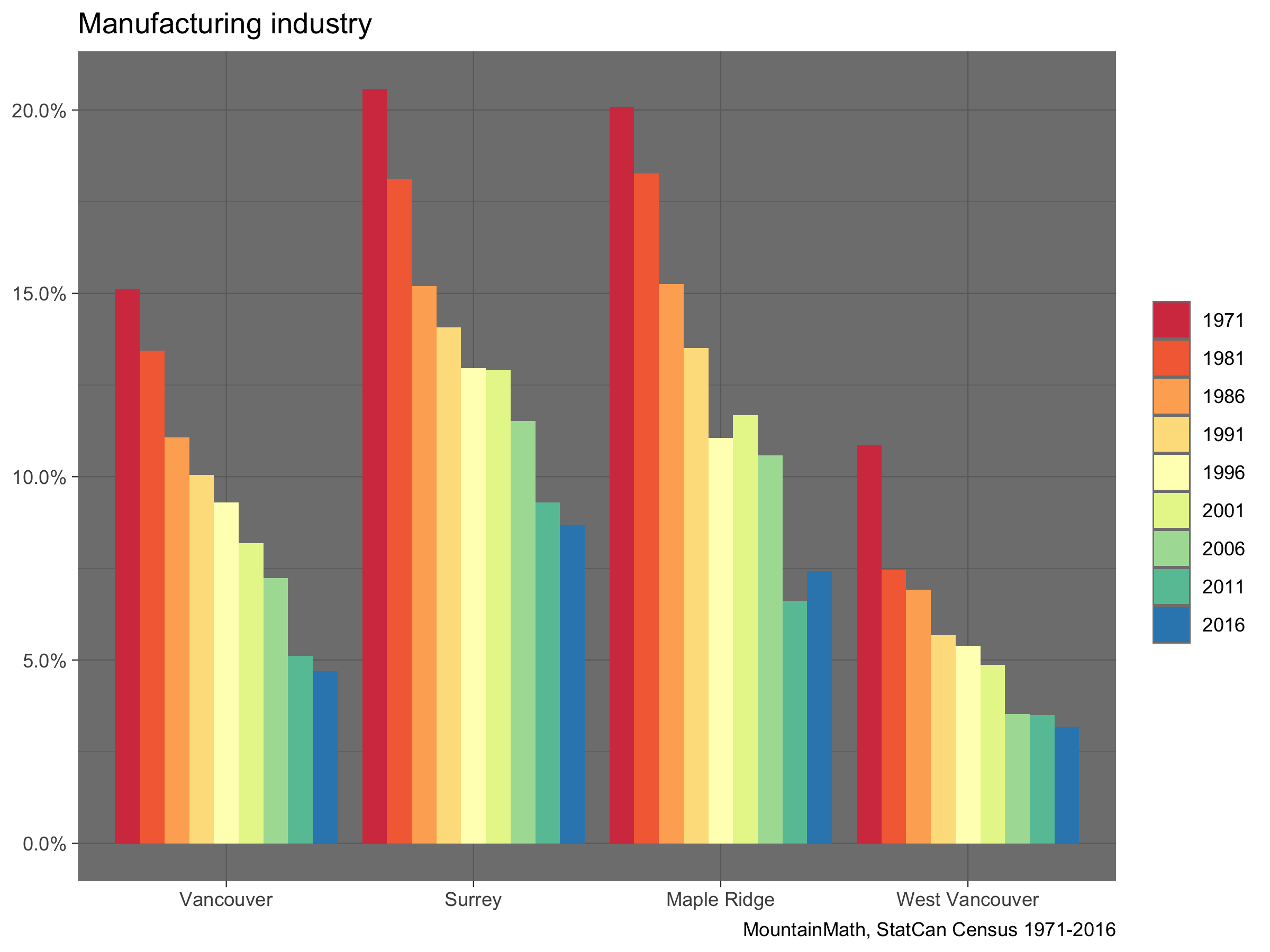

So if most of us are neither selling logs nor selling real estate, then what are we doing? Are we… making things? We’re certainly no Detroit or Hamilton, but the idea doesn’t seem too bizarre. After all, the rise of manufacturing drove the rise of big cities through the Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries. So let’s take a peek at manufacturing! Fortunately for us, it’s been pretty consistently defined since 1971. How’s it doing?

Woof! Back in 1971, manufacturing really had a claim in the region, accounting for more than one in five jobs in Surrey. It used to beat the Construction industry! But it’s declined precipitously - by roughly two-thirds - enabling the Construction industry to pull ahead. Hello North American de-industrialization!

So we don’t mostly sell real estate, we never mostly sold logs, and we don’t manufacture very much. What do we do? A big answer is Retail. Retail alone is nearly as large as Finance, Real Estate and Construction combined and surpasses Manufacturing. And it’s pretty evenly distributed across municipalities (even if it increasingly pays too little to get a place in West Vancouver).

What else do we do? We take care of people! Let’s have a look at Health Care and Social Services. Here we see a widespread rise over time across the Metro Region. Health and social services are now remarkably evenly distributed across our four exemplar municipalities.

Retail, health, and services are basic city functions, providing hubs for their surrounds. When it comes to more specialized services (e.g. Women’s and Children’s Hospital) Vancouver helps serve and take care of the entire province.

Finally, and perhaps trickiest to define, let’s briefly touch on the “Creative Class” as those often considered the drivers of our new, post-industrial economies. Popularized by Richard Florida, they’ve been understood as those “involved in the creation of new knowledge, or use of existing knowledge in new ways” (e.g. Cliffton 2008, p. 68). This is often defined rather loosely (those working in science, and maybe arts, and information and stuff) or via occupation. How could we think about it in terms of industry? Let’s smash together some things and see what happens. In our most recent era, 2001-2016, we can combine “Educational services” with “professional, scientific and technical services” as constitutive of a knowledge core with “Information and cultural industries” and “Arts, entertainment and recreation” as representing more of our aspirationally Bohemian, Hollywood North-type creativity. Unfortunately, back in the 1986-1996 period, we lose most of these categories, “Educational service” is there, but the rest is gone, probably absorbed into “Other services.” In 1971-1981, we don’t even get “Educational Service” broken out. What do we see across the Twenty-First Century so far? Is Vancouver increasingly creative?

Kind of! We can see a definite rise in the City of Vancouver itself, as well as in its largest suburb of Surrey. For Maple Ridge and West Vancouver, the historical patterns are less clear, but we get a real sense of geographic sorting. West Vancouver, in particular, seems to be a place that many of our “creative class” aspire to live. At least the ones that make money.

We note that in the City of Vancouver and in West Vancouver the creative class on it’s own clearly outperforms our widest possible categorization of the Real Estate related sector, whereas the situation is reversed in Surrey and Maple Ridge.

Overall, there is no evidence to support the zombie narrative that Vancouver once sold logs and now we sell real estate. Instead, we get the sense that Vancouver has a relatively diverse economy. It’s solidly backed by the supportive role in retail and services that the metropolis plays for the province as a whole. But its growth is arguably also supported by a rising “creative class” replacing older manufacturing jobs. Our industrial strength diversity leaves the region in a pretty good economic position. But adding a few more construction workers would really help with our housing shortage!

As usual, the code for this post is availabe on GitHub for anyone to reproduce and adaped. That data we used for this post is a custom tabulation that we have made use of before on several occasions that only covers the Vancouver and Toronto CMAs. Interested analysts can tweak the code to break out their own municipalities and industries.

Note

An earlier version of this post had a problem with graphs for multiple categories not stacking properly which has been fixed now. The previous version can be accessed in the GitHub version control.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2021-02-22 09:03:23 PST"## Local: master /Users/jens/Google Drive/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [69a0e31] 2021-02-22: exponential covid post## R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10)

## Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin17.0 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Big Sur 10.16

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRblas.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/C/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] mountainmathHelpers_0.1.2 forcats_0.5.0

## [3] stringr_1.4.0 dplyr_1.0.4

## [5] purrr_0.3.4 readr_1.4.0

## [7] tidyr_1.1.2 tibble_3.0.4

## [9] ggplot2_3.3.3 tidyverse_1.3.0

## [11] cancensus_0.4.2

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] tidyselect_1.1.0 xfun_0.18 haven_2.3.1 colorspace_2.0-0

## [5] vctrs_0.3.5 generics_0.1.0 htmltools_0.5.0 yaml_2.2.1

## [9] blob_1.2.1 rlang_0.4.9 pillar_1.4.7 glue_1.4.2

## [13] withr_2.3.0 DBI_1.1.0 dbplyr_1.4.4 modelr_0.1.8

## [17] readxl_1.3.1 lifecycle_0.2.0 munsell_0.5.0 blogdown_0.19

## [21] gtable_0.3.0 cellranger_1.1.0 rvest_0.3.6 codetools_0.2-16

## [25] evaluate_0.14 labeling_0.4.2 knitr_1.30 fansi_0.4.1

## [29] broom_0.7.4 Rcpp_1.0.5 scales_1.1.1 backports_1.2.0

## [33] jsonlite_1.7.2 farver_2.0.3 fs_1.4.1 hms_0.5.3

## [37] digest_0.6.27 stringi_1.5.3 bookdown_0.19 grid_4.0.3

## [41] cli_2.2.0 tools_4.0.3 magrittr_2.0.1 crayon_1.3.4

## [45] pkgconfig_2.0.3 ellipsis_0.3.1 xml2_1.3.2 reprex_0.3.0

## [49] lubridate_1.7.9.2 assertthat_0.2.1 rmarkdown_2.5 httr_1.4.2

## [53] rstudioapi_0.13 R6_2.5.0 git2r_0.27.1 compiler_4.0.3Reuse

Citation

@misc{industrial-strength-zombies-vancouver-edition.2021,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {Industrial {Strength} {Zombies:} {Vancouver} {Edition}},

date = {2021-02-10},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2021-02-10-industrial-strength-zombies-vancouver-edition/},

langid = {en}

}