Variants of concern are named such because they are concerning. The ones we worry about are B.1.1.7 (the variant first documented in UK), B.1.351 (the variant first documented in South Africa), and P.1 (the variant first documented in Brazil).

Currently, B.1.1.7 is probably the most concerning in BC because we know it is significantly more infectious, with a daily growth rate average of around 10%. This means that in our current BC environment, where we have been seeing a decline by about 0.7% a day since our tougher restrictions enacted in November, B.1.1.7 would grow at about 9.3% a day. As a comparison, we have seen roughly 5% daily growth between July 1 through mid November, with a brief period of lower growth around September.

The other two variants are concerning because they show some ability to escape immunity. This will have less of an impact short-term, but could cause problems down the road.

If B.1.1.7 becomes established in BC, it will grow at almost twice the rate as regular COVID-19 did this past fall. It will lead to chaos very quickly as several modelling approaches have tried to highlight.

What should we do?

- First we should try to prevent B.1.1.7 from being introduced. We must tighten up the quarantine rules so that we don’t get local transmissions. The first B.1.1.7 case recorded in BC transmitted to (at least) two other people. And with every week BC reported more local transmissions.

- If keeping B.1.1.7 out fails and we have local transmissions, we should prevent B.1.1.7 from becoming established. We want to aggressively play whack-a-mole whenever we see local transmissions and stomp it out. This is hard. If it wasn’t we would have done that with regular COVID-19 too. Fraser Health is now testing asymptomatic contacts to get ahead of transmissions and get to their contacts more quickly, and is also casting a wider net for contacts. It is not clear how other Health Authorities are dealing with VOC.

- If keeping B.1.1.7 from becoming established fails, we should act quickly to prevent it from growing. As we have seen over and over again, it’s much easier to slow or revert growth when the numbers are small. Exponential growth is unforgiving, especially when it is much faster than what we have seen in fall. If we wait until B.1.1.7 starts to visibly push up overall cases, numbers will surge, contact tracing will collapse, driving up growth even further. Caroline Colijn has a great post to demonstrate the benefits of acting early.

Data on variants

So how are we doing right now? That’s hard to say, we don’t have useful data. Which is quite surprising given how concerning everyone agrees the variants of concern are. By “useful” I mean data with dates and denominators. How many variants were found when, and how many samples were screened/tested for them? Also, it would be good to know which specific variants were found and if they were locally acquired or not.

Unfortunately BC does not make this data public. But there is some data on VOC that is available. Let’s review what we have and run through the variants of data we can use to make guesses at the missing data on variants.

Point-prevalence study

The point-prevalence study aimed to look at all COVID-positive samples between January 30 and February 5 and determine how many of them were VOC and which ones they were. For the process, the samples were first screened with a second PCR to look for the N501Y mutation common to the variants, and then sequence all those flagged for the mutation to determine which variant they were.

The BC PHO announced that the point-prevalence study found three variants, two B.1.1.7 and one B.1.351 out of 3099 cases, which is a very low rate. She explained that 30 cases screened positive for N501Y, but only three were confirmed to be one of the variants by whole genome sequencing. This looks like great data, we have dates and denominators. The problem is that the results, 3/3099 VOC, is implausibly low given other data we have as I have argued elsewhere using schoole exposures and overall reported variants. And only 3 out of 30 N501Y cases being variants of concern is also suspiciously low, screening should be quite good at picking out the variants.

The point-prevalence study should have been the comprehensive baseline for data on variants, but as much as it pains me to say this, unfortunately there are too many big questions to take her reported results at face value.

Situation reports

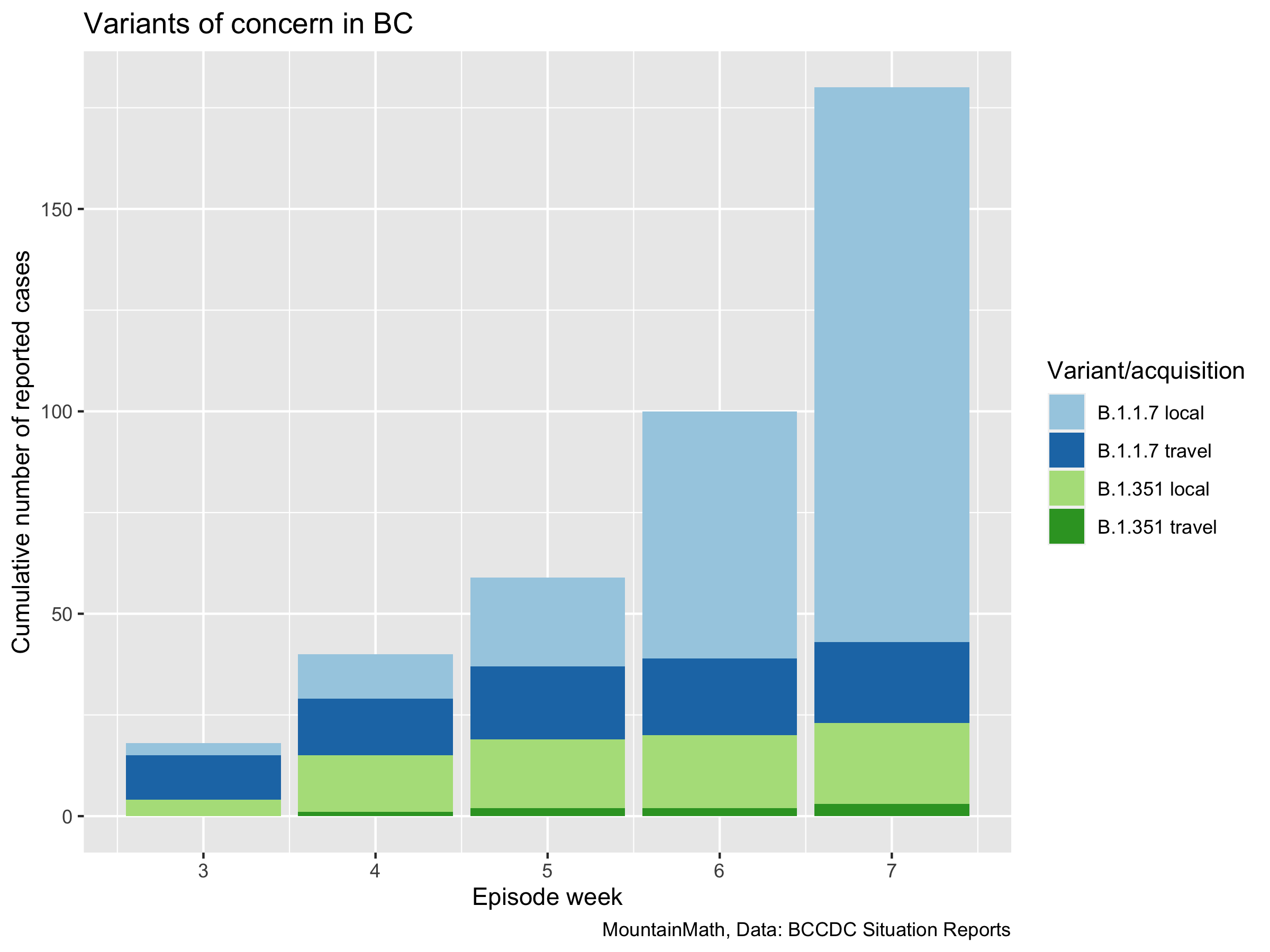

The weekly situation reports list cumulative variant of concern case counts by variant and acquisition, and they give a broad window of episode weeks in which they fall. We can look at week over week changes in the cumulative counts, but there is likely a lot of backfilling of older data happening and it’s unlikely the difference in cases can be attributed to the last reporting week. Moreover, we don’t know how many cases were screened for variants. We have fuzzy denominators and dates. At best. Let’s take a look.

We see a clear increase in cumulative variants of concern being reported in the weekly reports, with the newest one covering cases with onset date up to week 7 (Feb 14-20). We don’t have denominators since we don’t really know if the cases added to the cumulative total were from the previous week or from earlier. And we don’t know what fraction of cases got screened and sequenced.

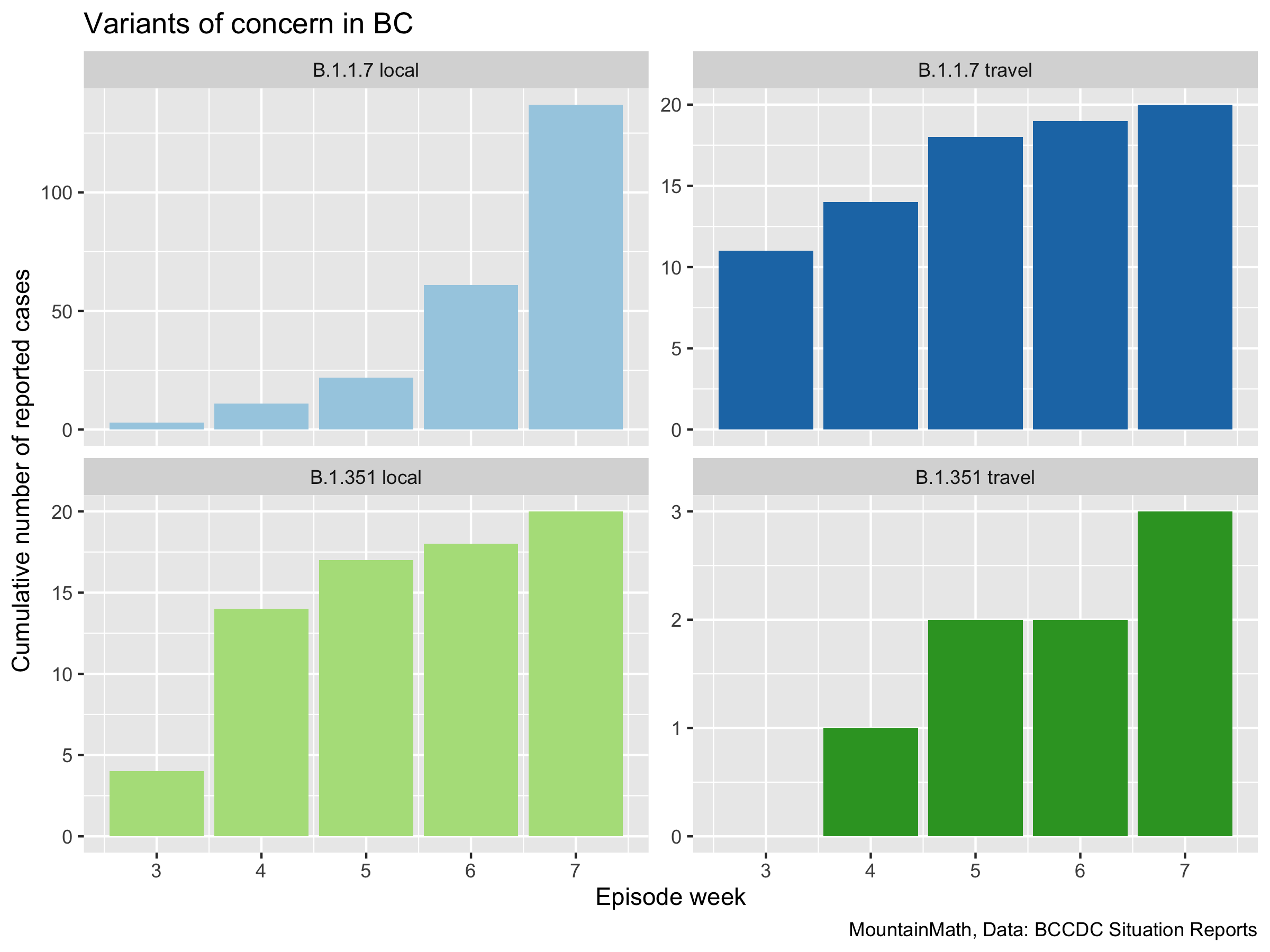

But not all variants are created equal. To see this we facet the graph by variants and acquisition, and allow the y-axis to scale independently for each graph so we can better see each individual one.

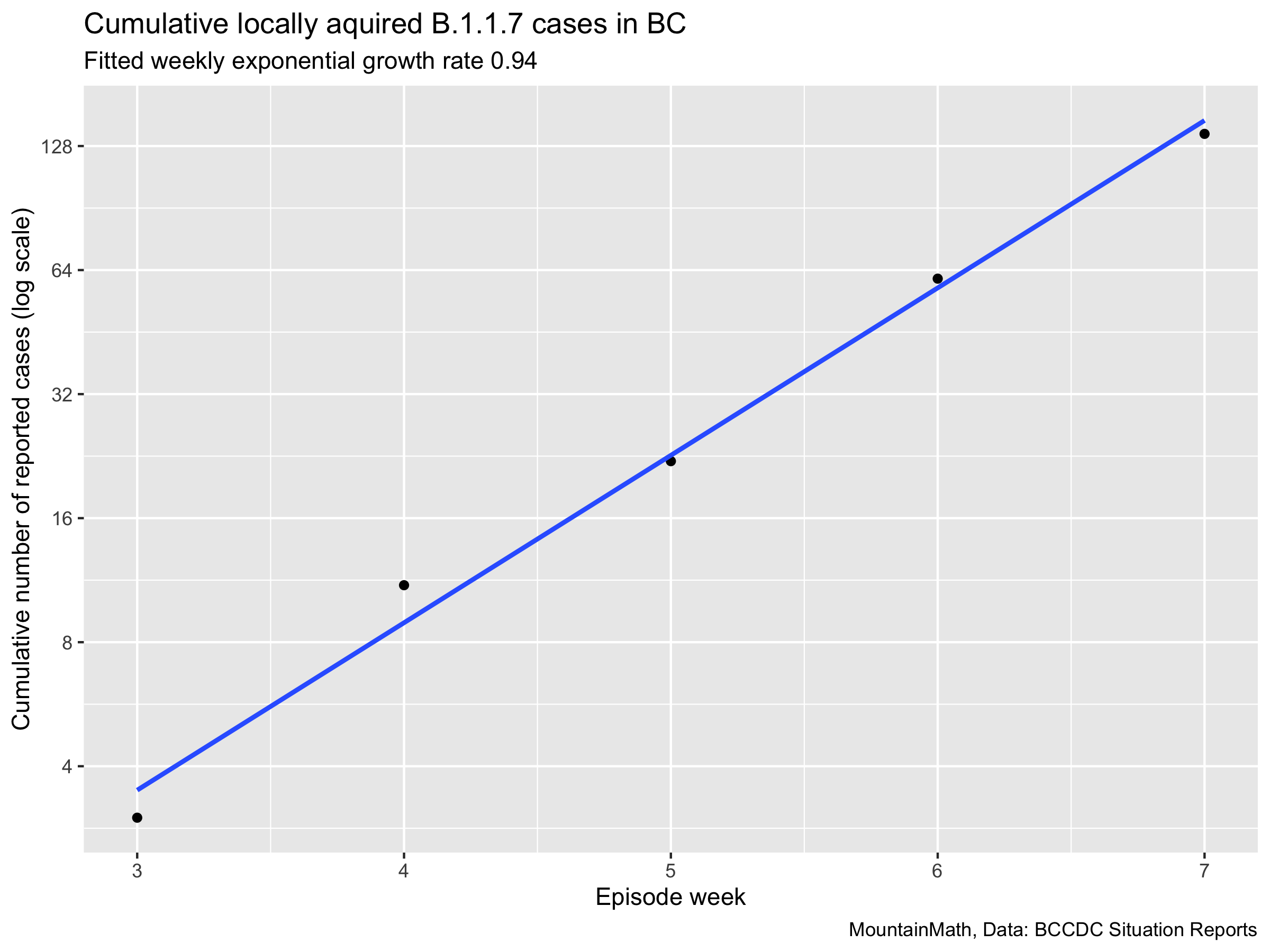

What we see is a neat exponential growth pattern for locally acquired B.1.1.7 cases. Let’s pull that out and fit an exponential to it.

We case almost doubled every week, that translates to a daily growth rate of 14%, which is higher than what we would expect. Growth rates tend to be higher at the start of variants taking off, just like they are at the start of any outbreak simply because “at the start of taking off” is conditional on the event “taking off”, so it is not implausible. However, understanding how the data got derived the growth rate is likely being pushed up by right-censoring getting better, so the backlog of old cases slowly clearing up, and the fraction of case samples increasing with time. We can’t pin down dates for these cases, and we don’t know the sample size. All this approach yields is some rough estimates.

School exposures

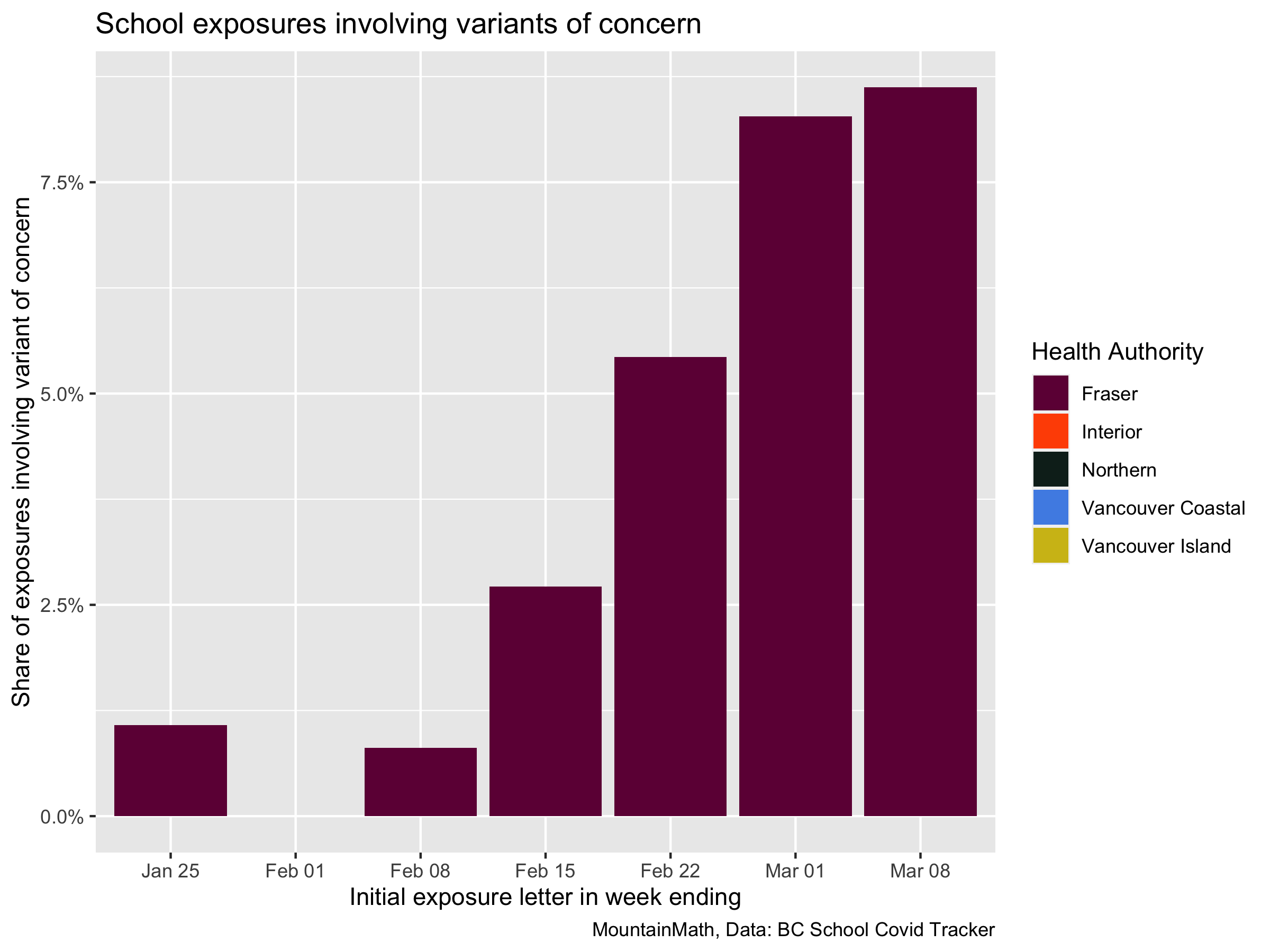

School exposures notices have dates, and at least in Fraser Health exposure notices get updated when they involve a variant of concern. That means we have dates and denominators, and we can look at the share of school exposures each weak that involved a variant of concern.

BC does not give out good data on school exposures, the list on the Health Authority websites are incomplete at the beginning period, and the information for exposures get updated when a new letter comes in and a different exposure at the same school is still active, making it hard to count exposure events without going through website scrapes.

Fortunately, the excellent BC School Covid Tracker meticulously collects and verifies exposure data and makes it available on their site. They provide a tremendous service that fills a data hole left by the province.

We look at the share of school exposures involving variants of concern for each week, where we split the week between Monday and Tuesday as exposure notifications coming out on Monday usually relate to exposures in the preceding week.

Fraser Health Authority is the only one reporting exposures involving variants of concern, either because these are concentrated in Fraser or because other Health Authorities choose not to update exposure notifications when they learn that they involve a variant of concern.

The last week for which we have complete data is the one ending March 1st, the next week only has two days of data at this point and exposure notification often get updated only a couple of days later because it takes time to screen for variants.

Estimates from data

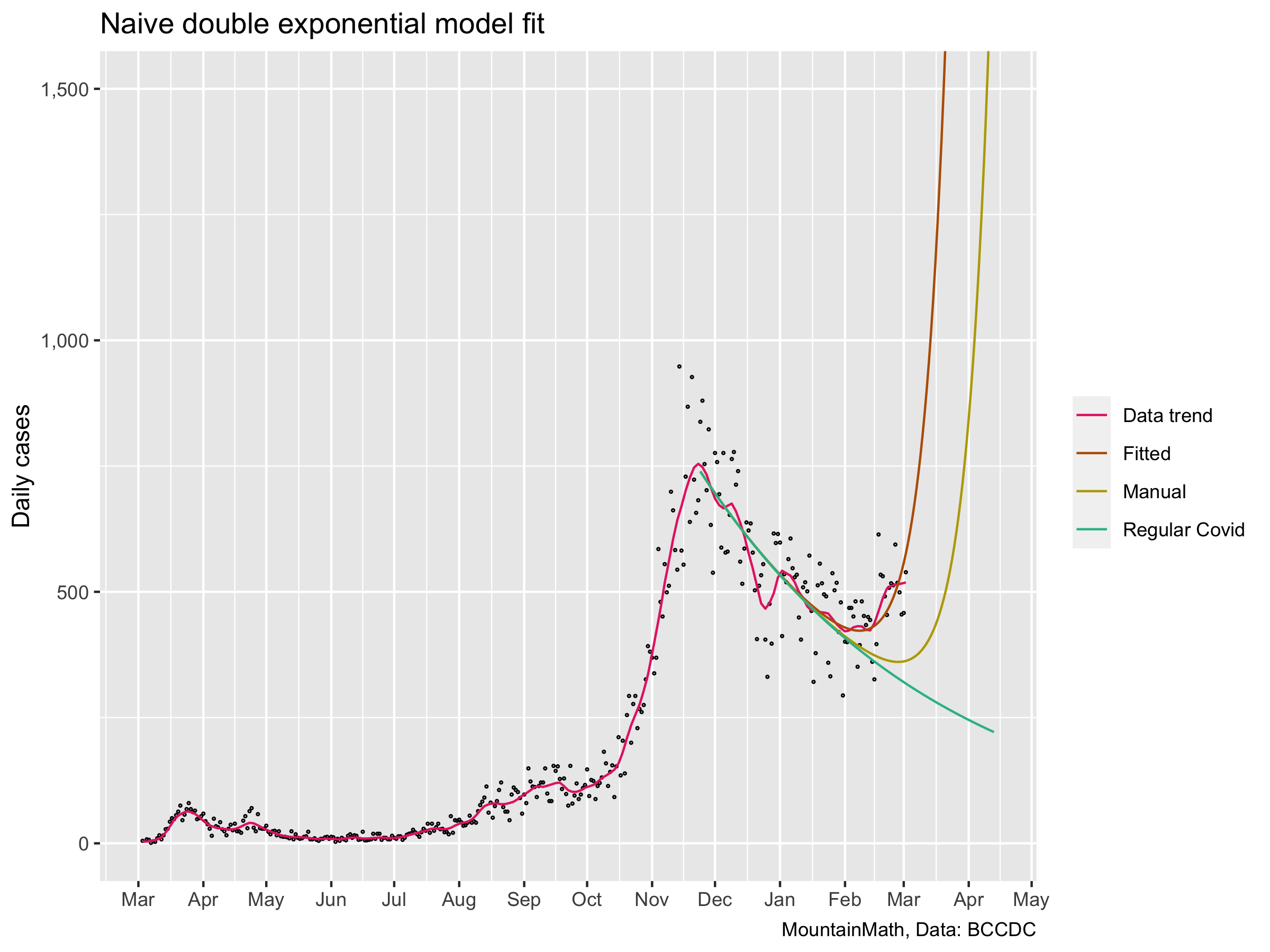

We have observed before that the entrance of the new variants, in particular B.1.1.7, means that we need to treat COVID-19 as two separate pandemics, regular COVID-19 and B.1.1.7. With B.1.1.7 having a daily growth rate of about 10% higher than regular COVID-19. This gives us an opportunity to estimate B.1.1.7 directly from the data, assuming that the only thing that changed recently is the introduction of variants and all other control measures stay about the same. In BC the growth rate has been fairly constant at -0.7% a day since the end of November, and we can fit a double exponential model to the curve with difference in growth rate fixed at 10% a day or 9.5% continuous growth.

This is a bit dangerous as such a fit will over-emphasize recent changes in cases. Which may have been caused by other events (e.g. a trivia night). But let’s give it a try. At the same time, we can also run a naive model that assumes three B.1.1.7 cases on February 2nd, which comes out to 21 cases in the point-prevalence week. That roughly jives with what we would expect from using exposure letters or B.1.1.7 case counts for week 5, the point-prevalence week.

We note that the double exponential model picks up the recent increase in cases and interprets it as being caused by B.1.1.7. And it predicts this rise to accelerate. This is likely not where we are actually headed, it would imply we had 163 B.1.1.7 during the point-prevalence week, which is too high given all the data points we have.

The “Manual” line is a more realistic scenario, but it is conditional on the assumption of 21 B.1.1.7 in week 5 and that our attempts to prevent B.1.1.7 from becoming established failed. The starting value of three daily cases on February 2nd is too low to assume simple exponential growth from them on, B.1.1.7 is likely still in it’s stochastic phase and may easily be delayed or accelerated by a week or two. So it’s hard to predict when exactly B.1.1.7 will take off, but once we are over 10 or 20 daily cases the growth will become very predictable.

Upshot

If these projections look scary, then that’s because they are. We now have some older people vaccinated, so that will reduce the death toll. But Long COVID will continue, and as cases shoot up contact tracing will break down and case growth will accelerate further.

That’s why variants of concern are concerning. And that’s why it’s important to monitor them closely, and that means have proper data. Which we still don’t have for BC. Ontario has now been sharing daily updates with variant screening results, which gives a minimal delay update on the share of variants. Which now make up over 20% of cases in Ontario. Using proxies can get a rough idea and the ballpark, but we need actual data to understand where we are at and make decisions on how to react.

As usual, the code is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt for their own purposes.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2021-03-04 09:56:40 PST"## Local: master /Users/jens/Google Drive/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [882992a] 2021-03-04: data variants## R version 4.0.3 (2020-10-10)

## Platform: x86_64-apple-darwin17.0 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Big Sur 10.16

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRblas.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.0/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/C/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] lubridate_1.7.9.2 broom_0.7.4 CanCovidData_0.1.5 forcats_0.5.0

## [5] stringr_1.4.0 dplyr_1.0.4 purrr_0.3.4 readr_1.4.0

## [9] tidyr_1.1.2 tibble_3.0.4 ggplot2_3.3.3 tidyverse_1.3.0

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] Rcpp_1.0.5 lattice_0.20-41 class_7.3-17 assertthat_0.2.1

## [5] digest_0.6.27 R6_2.5.0 cellranger_1.1.0 backports_1.2.0

## [9] reprex_0.3.0 evaluate_0.14 e1071_1.7-4 httr_1.4.2

## [13] blogdown_0.19 pillar_1.4.7 rlang_0.4.9 english_1.2-5

## [17] readxl_1.3.1 rstudioapi_0.13 blob_1.2.1 Matrix_1.2-18

## [21] rmarkdown_2.5 splines_4.0.3 labeling_0.4.2 munsell_0.5.0

## [25] compiler_4.0.3 modelr_0.1.8 xfun_0.18 pkgconfig_2.0.3

## [29] mgcv_1.8-33 htmltools_0.5.0 tidyselect_1.1.0 bookdown_0.19

## [33] codetools_0.2-16 fansi_0.4.1 crayon_1.3.4 dbplyr_1.4.4

## [37] withr_2.3.0 sf_0.9-7 grid_4.0.3 nlme_3.1-149

## [41] jsonlite_1.7.2 cansim_0.3.5 gtable_0.3.0 lifecycle_0.2.0

## [45] DBI_1.1.0 git2r_0.27.1 magrittr_2.0.1 units_0.7-0

## [49] scales_1.1.1 KernSmooth_2.23-17 cli_2.2.0 stringi_1.5.3

## [53] farver_2.0.3 fs_1.4.1 xml2_1.3.2 ellipsis_0.3.1

## [57] generics_0.1.0 vctrs_0.3.5 RColorBrewer_1.1-2 tools_4.0.3

## [61] glue_1.4.2 hms_0.5.3 yaml_2.2.1 colorspace_2.0-0

## [65] classInt_0.4-3 rvest_0.3.6 knitr_1.30 haven_2.3.1Reuse

Citation

@misc{data-variants.2021,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Data Variants},

date = {2021-03-04},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2021-03-04-data-variants/},

langid = {en}

}