(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

New parking proposal just dropped! As Vancouver City Council once again discusses parking it seems like a good time to give a brief overview of the trade-offs involved, with special focus on the progressivity of parking permit fees. Vancouver proposed to introduce a city-wide parking permit program, requiring residents to buy a $45/year parking permit to park their vehicles on city streets (reduced to $5 for people with low incomes), or pay a $3 overnight visitor parking fee. Additionally the City proposes higher annual fees of $500 to $1000 for new gasoline-powered cars built 2023 or later.

The motion reads:

The program consists of a pollution charge of up to $1,000 to be added to parking permit fees for more polluting vehicles 2023 or newer, as well as a $45 overnight parking permit for residential streets in the City that are currently unregulated, which would be reduced to $5 for people with low incomes.

To emphasize the key point the program has two components:

- A pollution charge for polluting vehicles 2023 or newer.

- A city-wide overnight parking permit for residentials streets of $45 (reduced to $5 for people with low incomes).

In this post we will mostly concern ourselves with the second component, this gets at the fundamental problem of privileging land use for vehicle storage above other uses and lays the groundwork for removing minimum parking requirements as explained in the motion:

An analysis of the feasibility and implications of removing the City’s regulatory minimum parking requirements for new developments will be brought back to Council at a later date.

Parking 101

To understand why this is being proposed let’s take a step back and take a careful look at parking. Don Shoup explains in his book The High Cost of Free Parking

Every transport system has three elements: vehicles, rights of way, and terminal capacity. Rail transport, for example, has trains, tracks and stations. Sea transport has ships, oceans and seaports, Air transport has planes, the sky and airports. Automobile transport has cars, roads and parking spaces. Two aspects of its terminal capacity set automobile transport apart from all other transport systems. First, automobile transport requires enormous terminal capacity - it is land-hungry - because there are so many cars and several parking spaces for each one. Second, motorists park free for 99 percent of their trips because off-street parking requirements remove the cost of automobile terminal capacity from the transport sector and shifts it everywhere else in the economy.

This hints at while it is so expensive to find land for people to live in Vancouver, it is free to find land for cars to park. This is how we designed it. We have strong restrictions on building space for people to live, and at the same time strong requirements to provide space for cars to park. This also links into the growing phenomenon of people living in their vehicles in Vancouver.

This hints at while it is so expensive to find land for people to live in Vancouver, it is free to find land for cars to park. This is how we designed it. We have strong restrictions on building space for people to live, and at the same time strong requirements to provide space for cars to park. This also links into the growing phenomenon of people living in their vehicles in Vancouver.

In the words of Don Shoup:

We have free parking for cars and expensive housing for people. We’ve got our priorities the wrong way around!

For example, the City of Vancouver requires one off-street parking space for every 28 gross square metres of space used as a detoxification centre, but one for every 9.3 square metres of space used as a bingo hall, only counting the area of the actual hall. A curling rink needs to supply three off-street parking spaces for every ice sheet, two spaces are needed for every racquet court. A one-family dwelling with suite and laneway house needs at least one off-street parking space, but a side-by-side duplex with one secondary suite needs three off-street parking spaces even though it has the same number of dwelling units.

If this sounds ludicrous and like pseudo-science, then that’s because it is. But why do we have minimum parking requirements like this in the first place? Does a curling rink in the West End really need to provide the same number of parking spaces as (a hypothetical) one in Southlands? What’s wrong with letting people decide how much off-street parking space they need? If a family wants to go car-free, that should be encouraged. But in Vancouver a family can’t buy a condo without a parking space. We are forcing car-free families to pay extra for something they don’t need. How much extra? It costs about $200 to $250 per month to finance and maintain an underground parking stall. That’s a lot of extra cost for something a family does not need.

Wait, an off-street parking space costs $200 per month? Who pays for that you might ask. The answer is: Everyone. That’s because the cost of off-street parking is bundled with other services.

Parking is bundled

Because we require so much parking, parking is over-supplied. And we can’t charge the true price for the cost of parking. But someone has to pay for it, and we do this by bundling parking with other services.

When you buy a condo, it comes with a parking space and the price of parking becomes part of the price for the home. Maybe you have the option of buying an extra space, or not buying any parking, but the cost or savings for that rarely amount to the ~$50,000 that it costs to build, finance and maintain that space. Part of that space is cross-subsidized with the cost of your living space.

Similarly, when you are renting there may be a an extra charge for a parking space. But that charge will typically run around $60 and not the $200 to $250 it actually costs. Who pays the rest? You pay for that through your rent. And if you choose not to rent a parking space, and your neighbour gets a second car and buys that extra space for $60, you are still cross-subsidizing your neighbour’s second car parking spot to the tune of ~$150/month through your rent.

When you go shopping you often don’t pay for parking. But the store is (hopefully) not losing money, they pay for it through higher prices on the groceries you are buying. You walked to the store to get groceries? You still pay for someone else’s parking spot.

We make driving artificially cheap and cross-subsidize that by making housing and shopping more expensive. You think that’s messed up? Yup, that’s messed up. But that’s how we roll. As Don Shoup famously noted in his influential article “The High Cost of Free Parking”:

Minimum parking requirements act like a fertility drug for cars. Why do urban planners prescribe this drug?

This is crazy, and it needs to change. We need to get rid of off-street parking requirements and let people decide if they want parking with their housing or if they don’t. But there is a catch. As long as on-street parking is free or cheap, people will simply store their vehicles on the street if we stop requiring off-street parking. In fact, the whole reason we have these off-street parking requirements in the first place is to keep street parking free.

Historically, as cars arrived in cities, they started to clog up space when parked. There were essentially two ways people solved this problem of streets clogged by parked cars. Some places, like North America, solved this by requiring ample off-street parking, so on-street parking would not be scarce. Others, like Tokyo, solved this by requiring people wanting to register their car to prove that they had an off-street parking space. In North America everyone pays for the cost of parking, whether they use that parking or not. In Tokyo, only drivers pay for their off-street parking spot.

The need to manage on-street parking

This brings us back to the city proposal. If we want to rectify the ridiculous situation where we force people to pay upward of $200 a month for parking they don’t use, we need to tackle the problem of congested on-street parking. And there is an effective solution to this tragedy of the commons: Charge the lowest price so that about 20% of spaces are available for people to park. This means that the resource of street parking is well-utilized while anyone who wants to park can find parking. Vancouver already does exactly this along commercial areas, where parking fees are performance-based. Parking utilization gets monitored, and when utilization goes down the city drops the prices. If utilization goes up, the city raises them.

The new city proposal expands this to residential parking. It establishes a (nominal) baseline fee of $45 per year for a parking permit, with the possibility of raising these fees if parking becomes scarce. We have already seen something like this in the West End, where the city has introduced significantly higher parking fees for new vehicle registrations while grandfathering in old registrations at a lower rate that also applies to low-income households.

A system to manage on-street parking is a necessary step in order to drop or significantly lower off-street parking requirements.

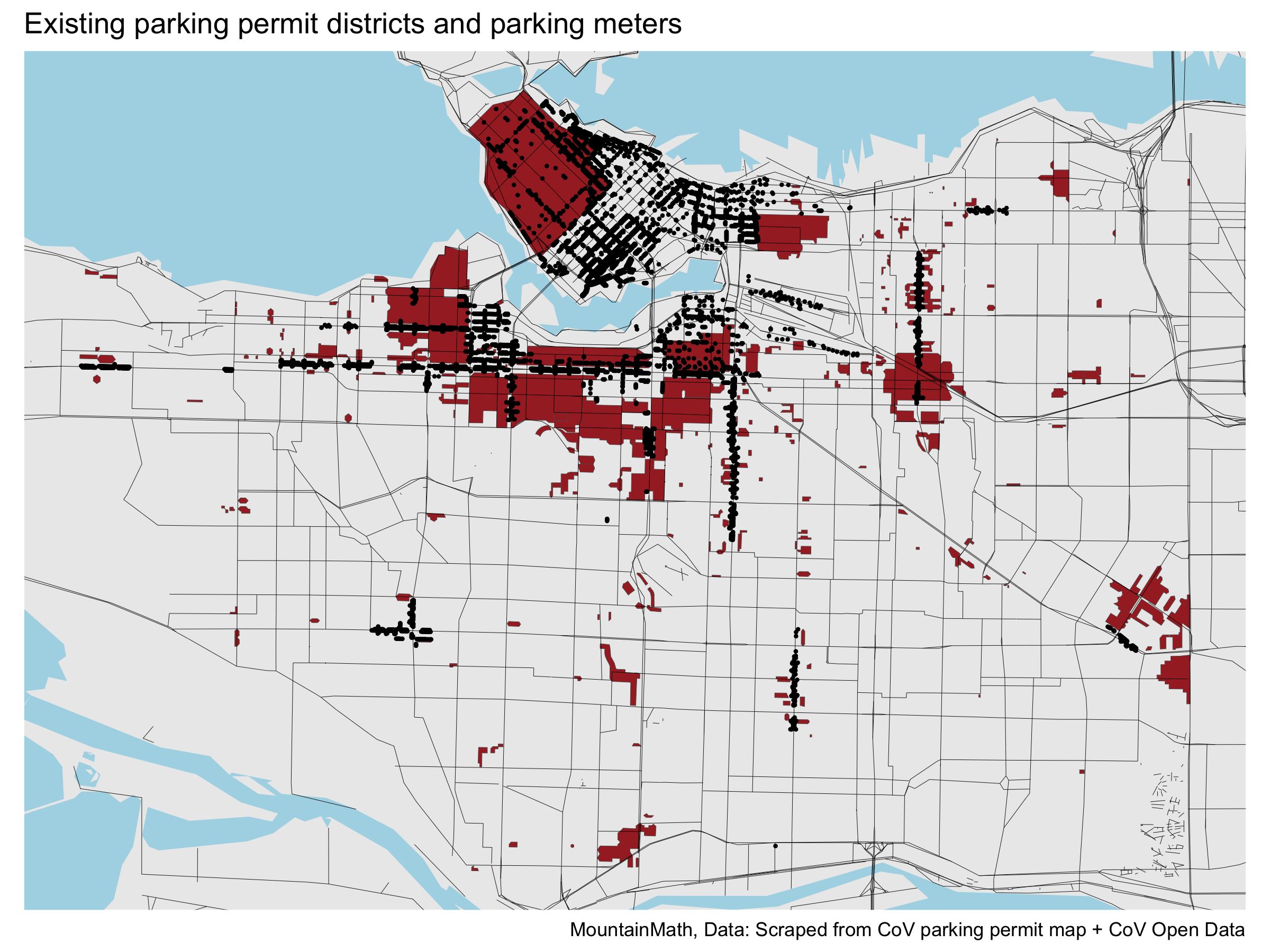

Existing parking permit districts

Some areas of the city are already covered by permit parking zones, so they won’t be affected by the rule change. Other areas, like Yaletown or Coal Harbour, are essentially covered by metered parking, or don’t allow parking at all.

While the parking meter data we have gives only approximate coverage of the metered areas and does not contain information on parking restricted portions, it is worthwhile to estimate characteristics of the population already covered by paid permit parking. In those areas 20% of the population is in low income (LIM-AT) compared to 19% in the City overall, and 70% of households are renting compared to 53%. In total 33% of City of Vancouver renter households live in existing paid parking permit areas.

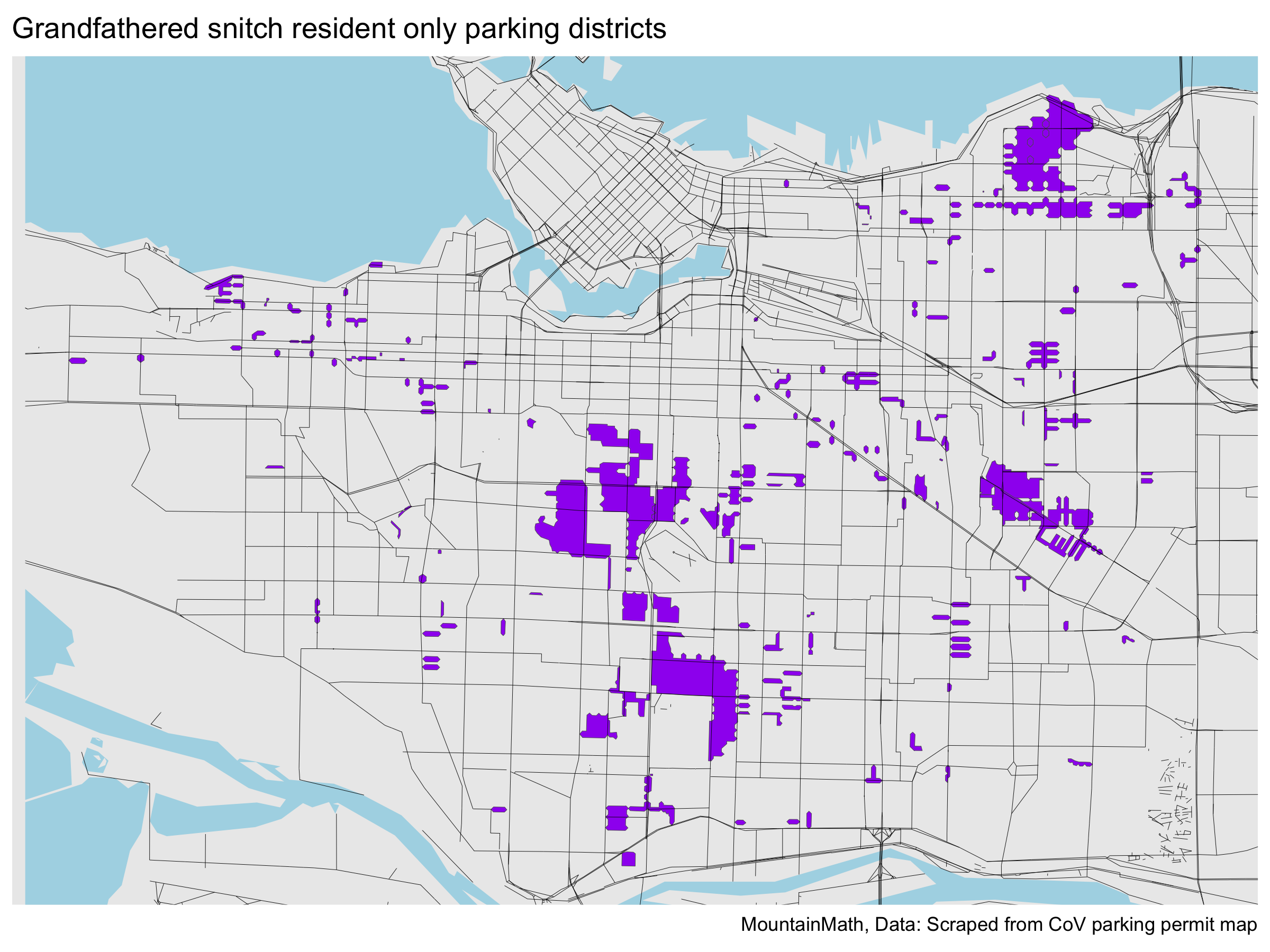

Additionally the city has residential only parking districts that don’t require permits and don’t require paying a fee. They operate on a snitch basis, where residents can park on their block and enforcement is only on a complaint basis, where residents call in when they observe non-residents parking on their block.

These are zones where residents have managed to secure exclusive access to public street parking without having to pay for it. Unsurprisingly, low income people at 16% of the population and renters at 43% are under-represented in these areas.

The new proposal would expand paid parking for overnight parking from the current permit parking zones to the rest of the city, including the no-permit snitch-enforced residential parking only areas.

Equity

Don Shoup observed in his book that

[parking requirements] increase traffic congestion and air pollution, distort urban form, degrade urban design, increase housing costs, limit homeownership, damage the urban economy, harm the central business district, and penalize poor families.

Yet just like clockwork, whenever a policy change gets proposed that might inconvenience upper middle class people, like increasing property taxes - or in this case charging for parking - the ample evidence concerning how the existing policies hurt poor people gets ignored and wealthy people explain: “But this will hurt low-income people!”

While many planners have changed their view on parking and are pushing for change, it should not be surprising that some of the most outspoken critics of change are also planners, who after all created and upheld the perverse minimum parking requirements that privilege cars and car ownership and disproportionately hurt low-income people. And the proposed $45 per year ($5 for low income people) pales in comparison to the ~$200/month planners have imposed on car-free low income people in this city.

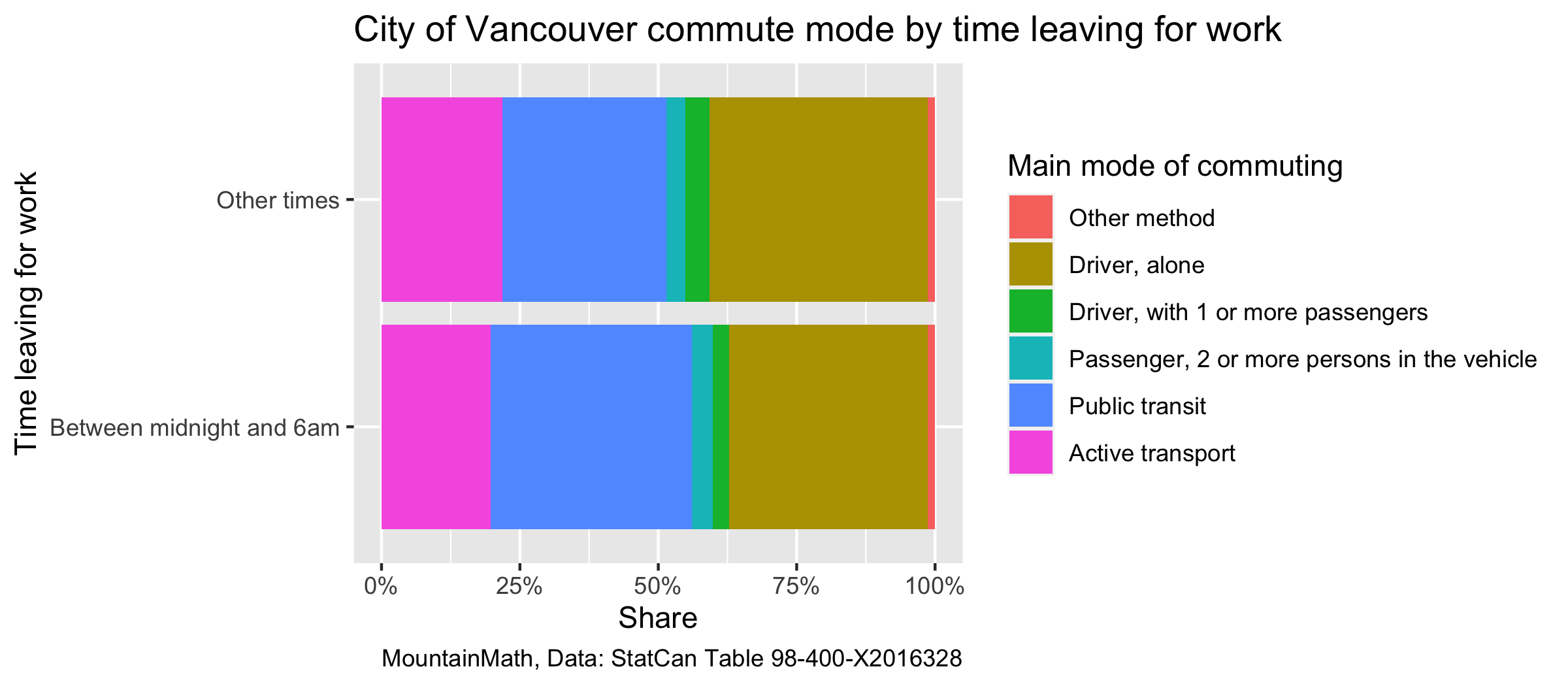

For example one local commentator noted correctly that “18 per cent of workers who are living in Vancouver have starting or ending commute times that might not fit into the transit schedule because they start between midnight and 6 a.m.” where “the start times don’t match transit schedules”, but conveniently failed to mention that those living in the City of Vancouver and commuting to work between midnight and 6am are more likely to to take transit and less likely to drive to work than people commuting to work at other times.

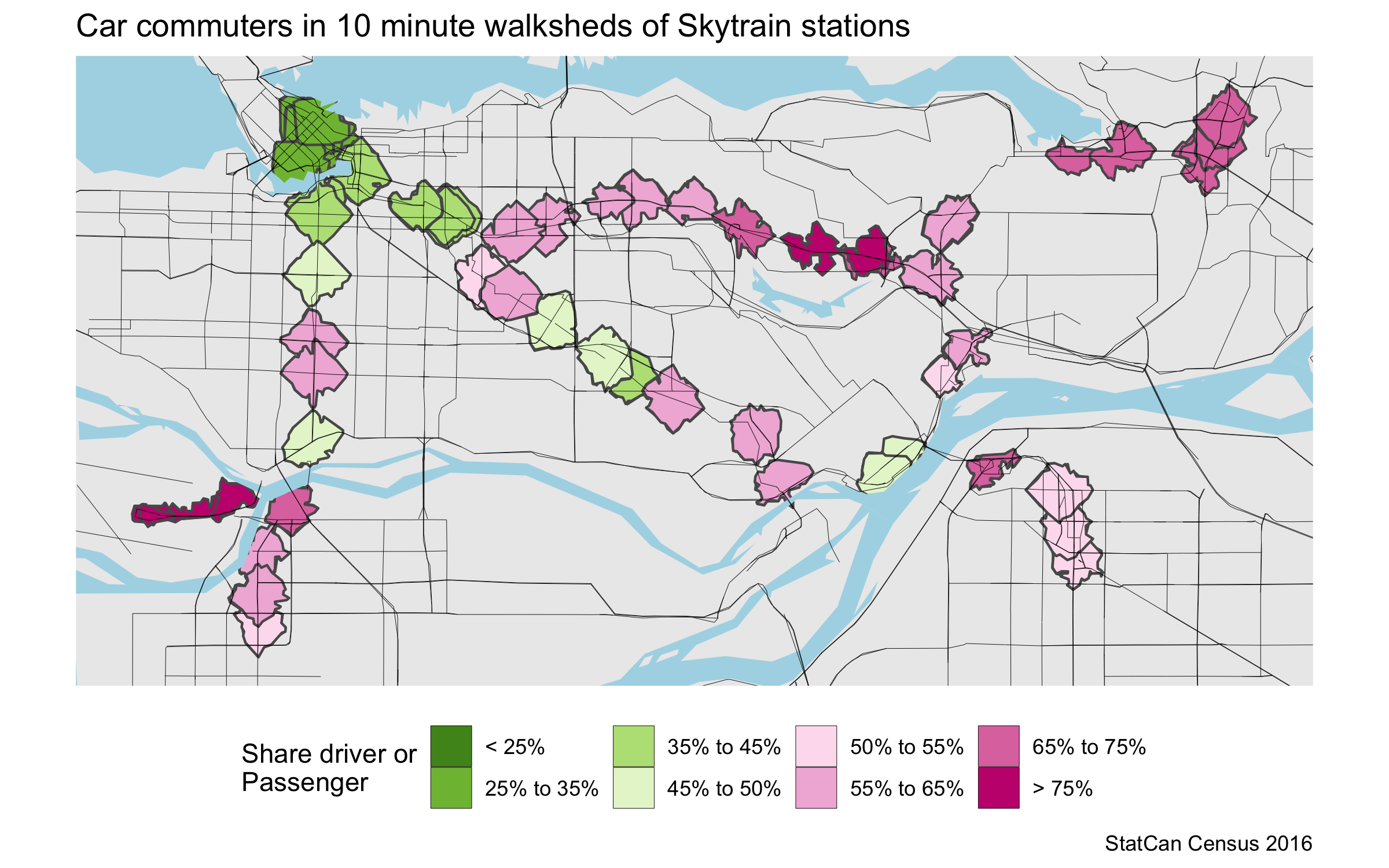

Others make vague arguments about which neighbourhoods get impacted by parking fees, citing neighbourhood level aggregate stats without ever attempting to understand how this relates to individuals. Claims like half of commuters driving or being driven to work […] in areas with rapid-transit stations (with the exception of Downtown and Strathcona) are also not helpful. Examining mode share to work from the 2016 Census in the 10 minute walk sheds around skytrain stations show that this is selling several stations short.

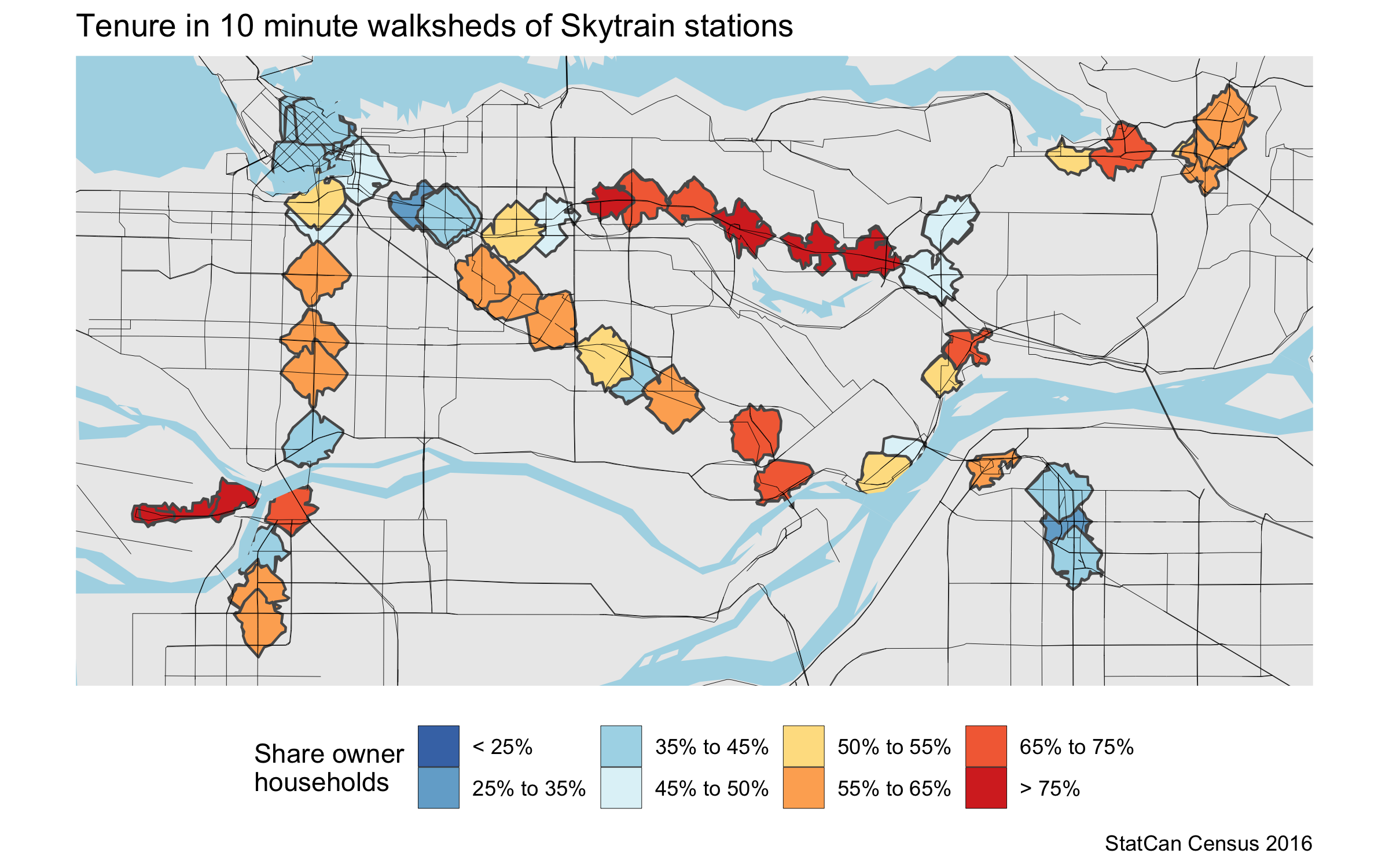

There are however stations with catchment areas still showing a high share of car commuters, which incidentally coincide with the stations where low-density land use and elevated share of owner households remain.

Additionally, much of the catchment areas of stations around regions with higher density land use are already covered by existing permit parking zones.

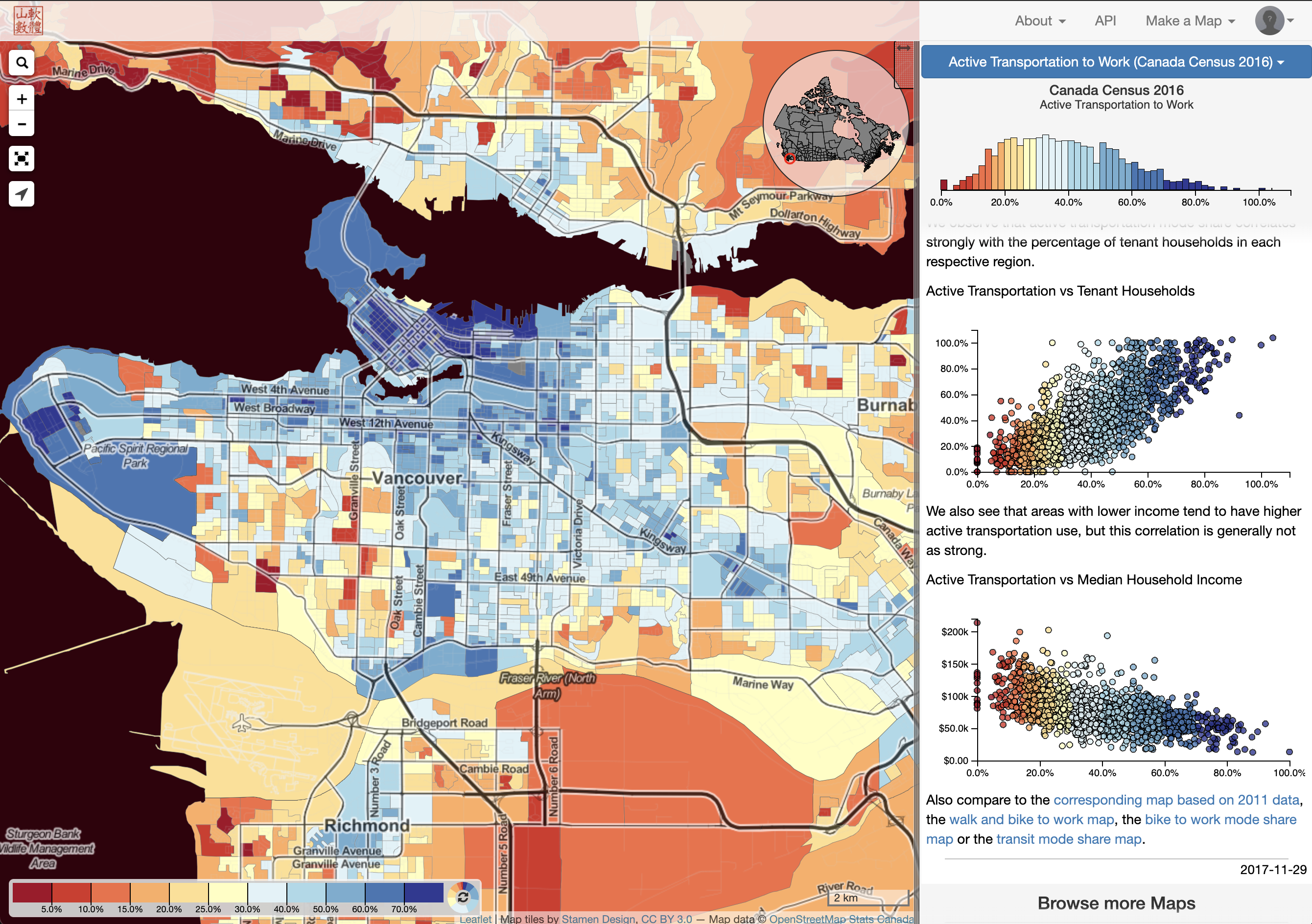

We can also explore fine-area ecological correlations between mode share, incomes and tenure using our CensusMapper map from 2017. While ecological correlations are known to be misleading at times, at fine levels of analysis they can provide insight into geographic variation. And they reflect the same trends. Lower income commuters are less likely to drive to work.

What all this tells us is what we pretty much knew already. Higher income people drive more than lower income people, owners drive more than renters, and our current setup of bundling parking disproportionately hits lower income people and renters. That’s the real equity issue here. Worth remembering as well that the big fees being charged apply only to new gas-guzzling vehicles which lower income people are least likely able to afford!

That is not to say that all equity concerns are unfounded. There are some real equity concerns that come with almost any policy change, and parking is no different. There are winners and losers, and some of the losers are lower income people. Moreover, charging for parking only works if people have alternatives to fall back on. The City of Vancouver is in a fortunate position of having almost universal frequent transit coverage, and it is relatively easy to expand this to the few missing places. Still, the level of service varies considerably throughout the frequent transit network.

But for some people this may not be a viable alternative even when they live close to transit. Disabled people come to mind, and switching from driving to other modes of transport might be unduly burdensome for them. That’s why the City of Vancouver proposal exempts vehicles equipped to transport wheelchairs. More broadly, the city has amended their initial proposal to charge everyone else $45/month to park overnight to lower this to $5 for people in low income, similar to analogous exemptions already in place for the West End parking plan. There is definitely work to be done around the edges of changing the rules for parking, and the City appears to have done just that.

The bigger equity picture

But is it really just work that needs to be done around the edges, or is something like charging for parking regressive on average? In that case, tinkering at the edges won’t be enough. Who benefits from the status quo and who doesn’t? Does Don Shoup’s statement that parking requirements “penalize poor families” hold in today’s Vancouver? Let’s take a look at Vancouver data.

To understand equity issues we are interested in the relationship of driving and car reliance to income and other socio-economic factors at the individual level, understanding this question needs cross tabulations at the individual person or household/family level.

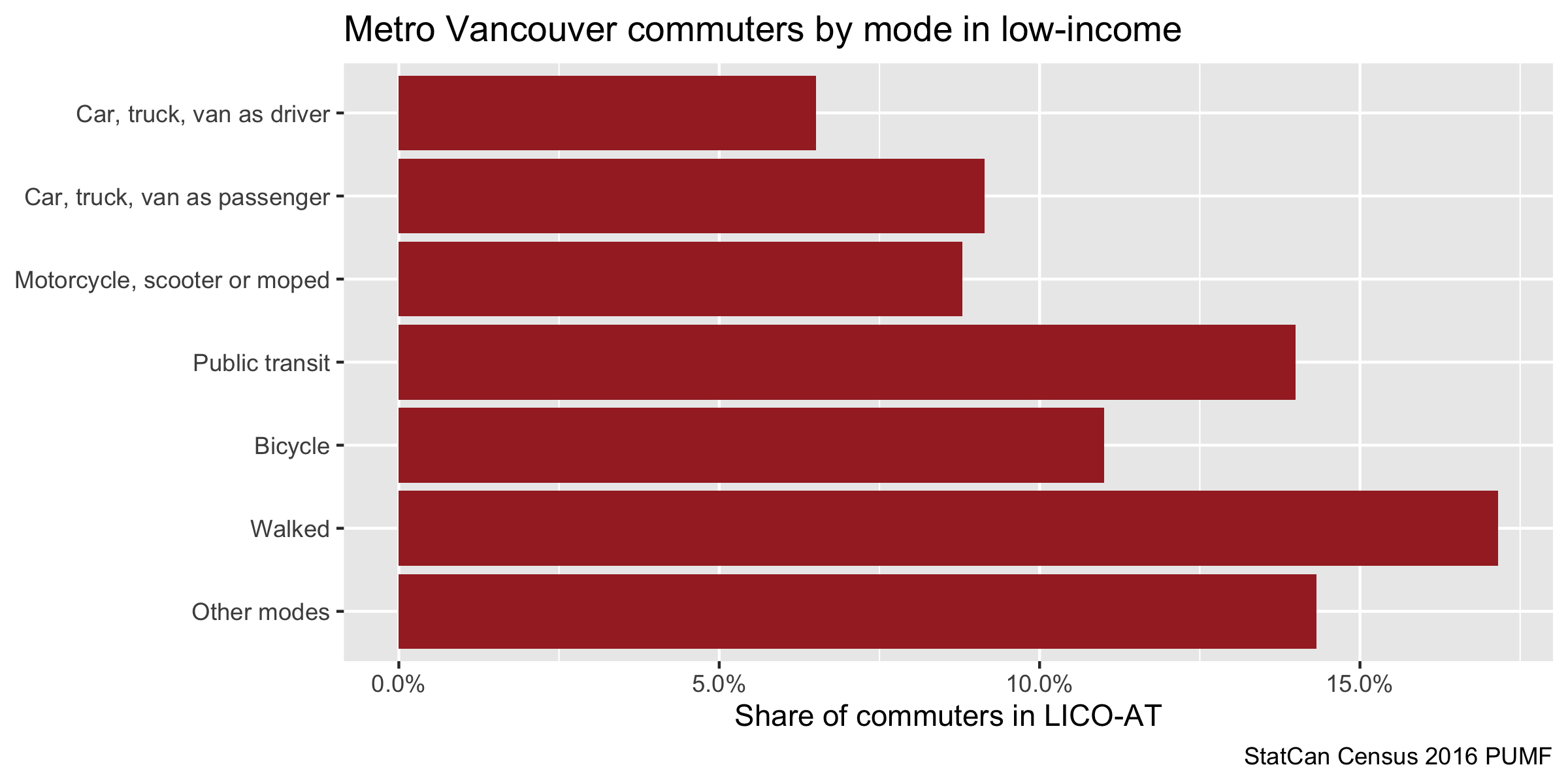

Census data can inform on this, and while we don’t have a city level cross tabulation on income and commute mode to work available we can check the Metro Vancouver level relationships using PUMF data.

The results are of course not surprising, drivers have the lowest share of low-income commuters. After all, owning and operating a car is expensive! This means the status quo hits low-income commuters the hardest as they disproportionately pay for car parking they don’t tend to use as much, be at their home, shopping, or in many cases also at work where parking continues to be subsidized.

But are these Metro level relationships still valid at the City level? And what about trips other than going to work, or more generally, just owning a car?

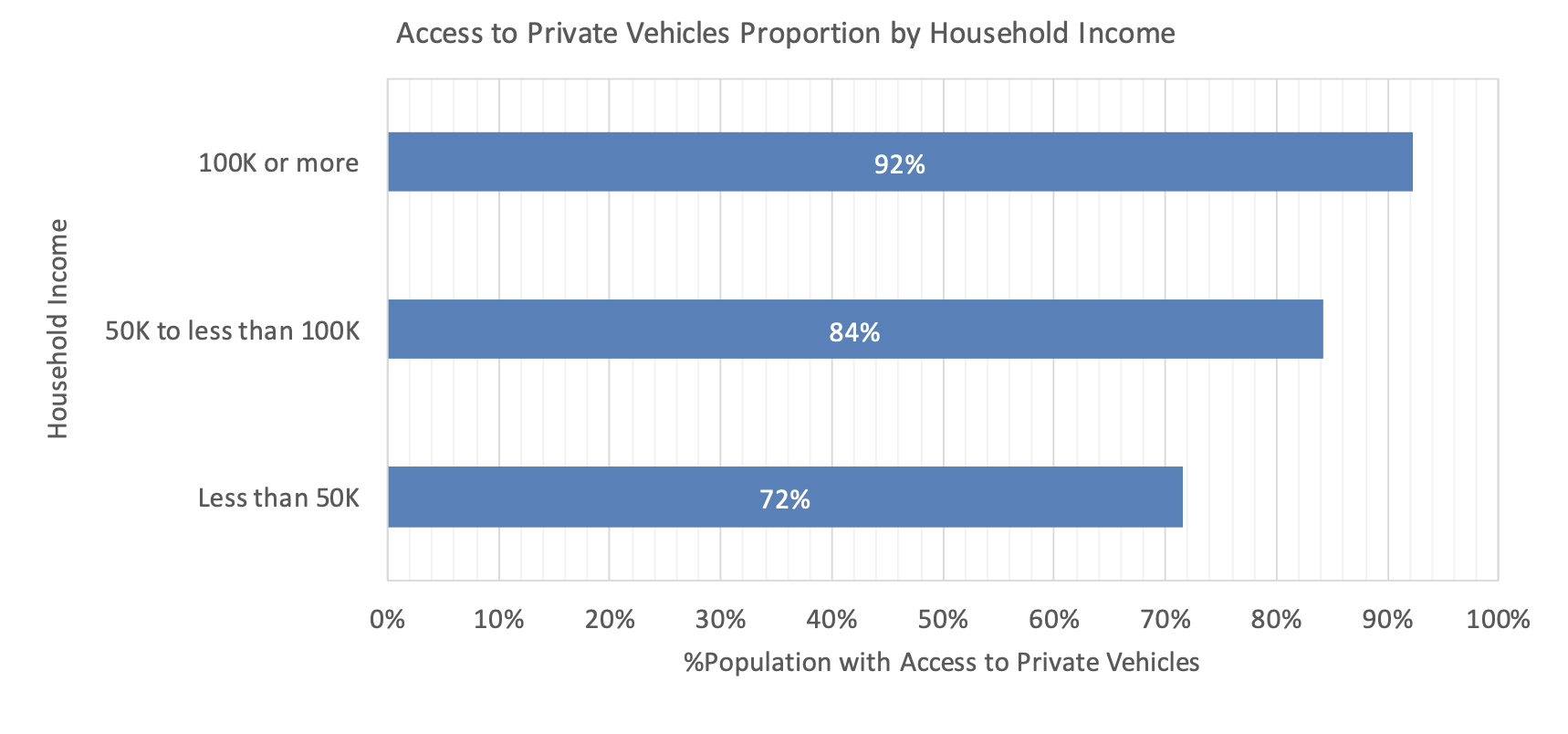

The 2019 City of Vancouver Transportation Panel Survey has information on incomes and car ownership and usage. We can confidently note that higher income people are more likely to have access to private motor vehicles.

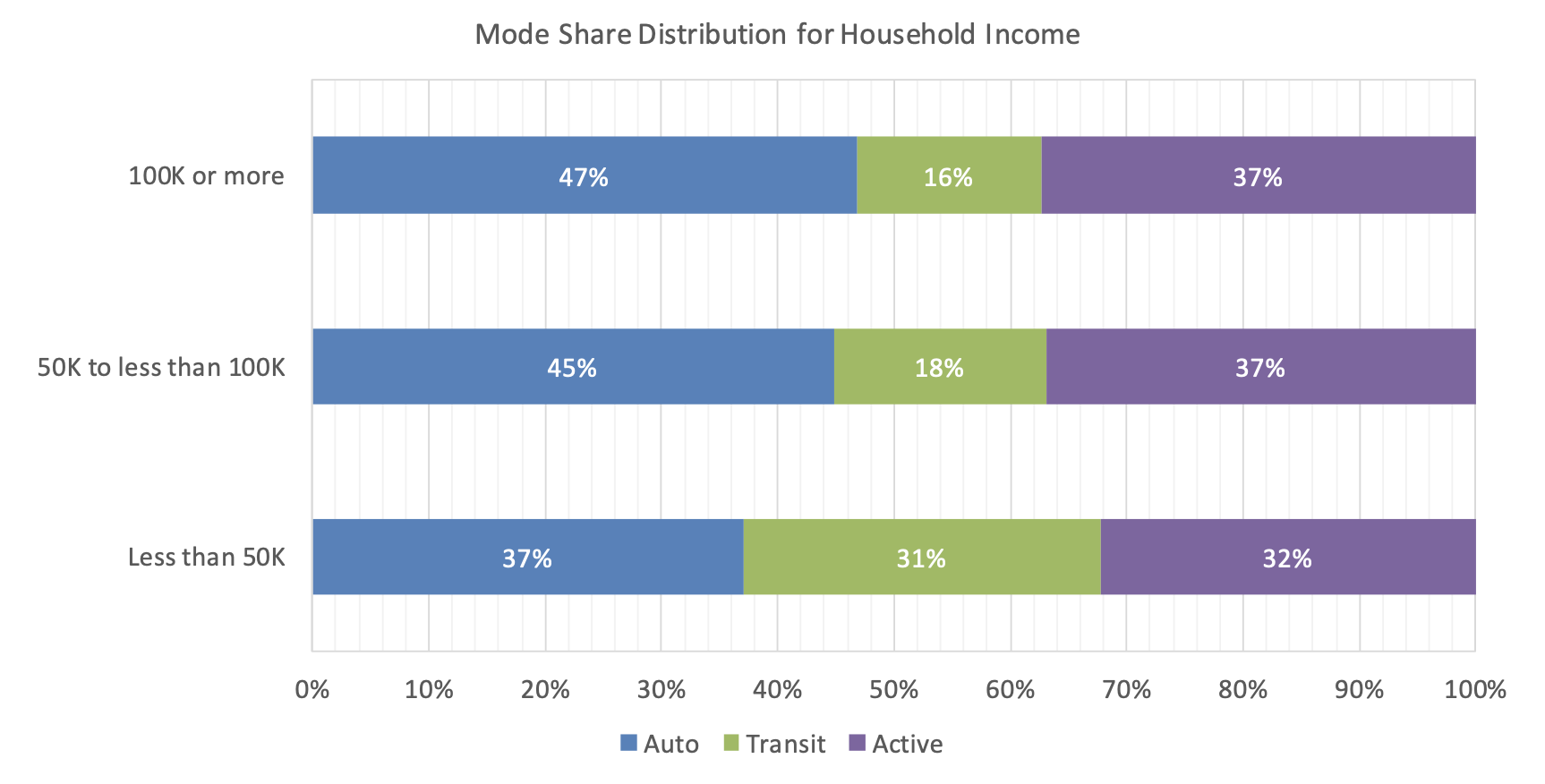

Similarly, higher income people are more likely to use private motor vehicles for trips (not just counting trips to work).

Similarly, higher income people are more likely to use private motor vehicles for trips (not just counting trips to work).

This shows quite clearly that low income people have been particularly hurt by our massive planning failure of making parking cheap and socializing the cost of parking into housing and the price of goods and services. And to add insult to injury, low income people are also most impacted by the induced car dependence as well as downstream effects on climate.

But these are average effects, and even if we undo minimum parking requirements today it will take time to unlock the benefits of reversing almost a century of planning malpractice. This tells us we should pay more attention to the individual level short-term changes, and ask how to structure the transition in a way that minimizes stress on low-income populations.

Upshot

What have we learned from all of this? The City of Vancouver is no outlier in how existing parking regulations adversely impact low-income populations. This proposal, putting in place a mechanism to charge for on-street parking city-wide, is a necessary step in reversing one of the most profound planning failures: minimum parking requirements.

Yet change is hard and affects different people differently, and it will take time until citizens can reap the benefits of removing minimum parking requirements. To ease the transition the proposal significantly lowers the fee for low-income people, from $45 to $5. Down the road prices for street parking permits may increase depending on demand, just like we have already seen in the West End. Grandparenting and discounts for low-income populations - as in the West End - can ease that transition.

If planners had paid as much attention to affordable housing as we have to affordable parking, Vancouver would be a very different city. It is good to see that city planners are realizing this and are taking steps to adjust their priorities. The benefits of this won’t materialize overnight, but this city-wide permit parking proposal is an important and necessary step along the way.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{fixing-parking.2021,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {Fixing Parking},

date = {2021-10-03},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2021-10-03-fixing-parking/},

langid = {en}

}