(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

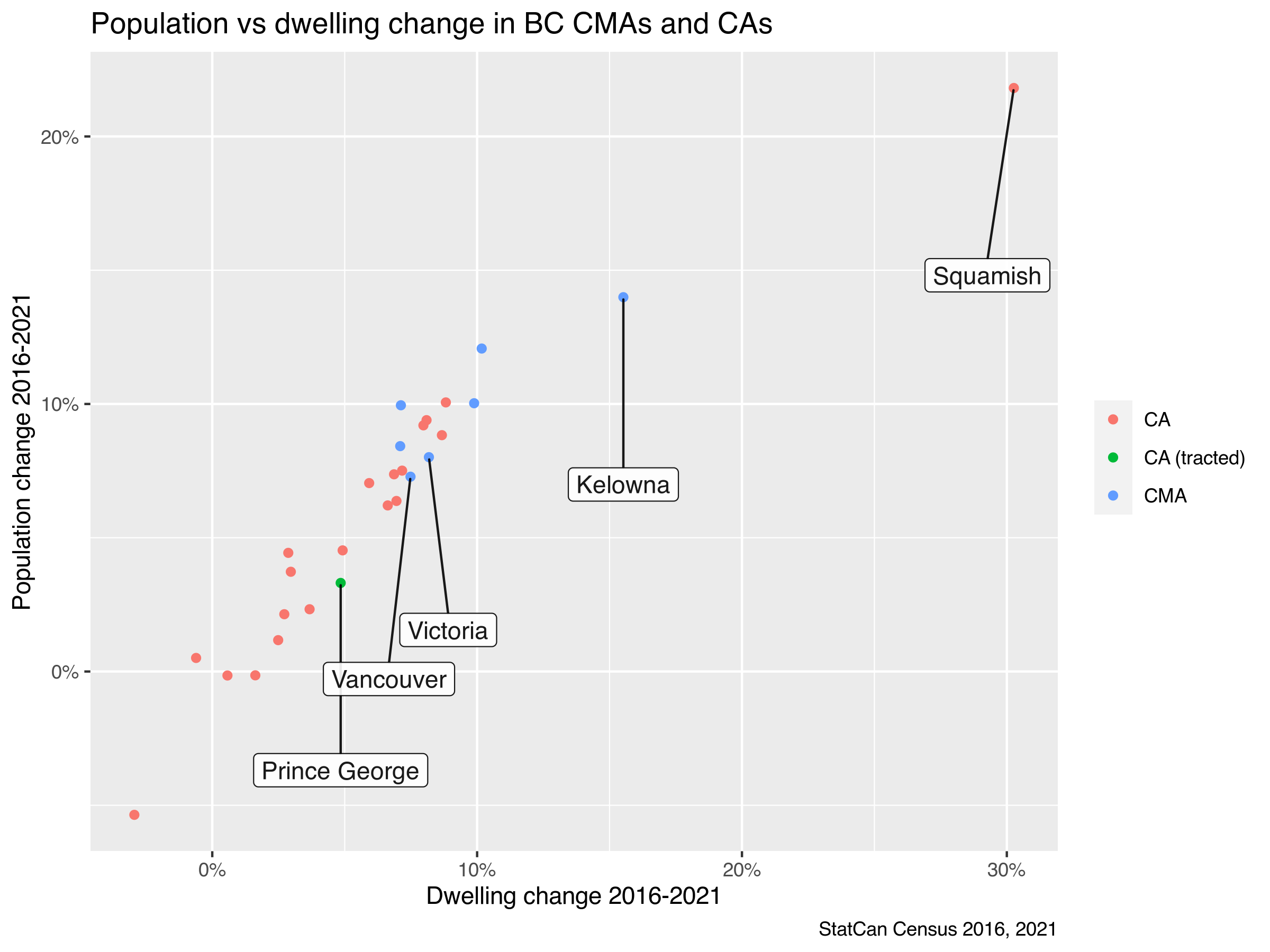

In our previous post we have outlined the broad problems with the recent UBCM report, in this post we return to one particular one, the comparison of dwelling growth to population growth for “BC Major Census Metropolitan Areas” (Figure 2 in the report), paying particular attention to Squamish as the largest outlier. To start out, let’s take a comprehensive look at how dwelling and population growth play out across BC’s CMAs and CAs.

We see a strong correspondence between dwelling and population growth as one would expect. The UBCM report picked out the Major CMAs Vancouver and Victoria, and with Kelowna the next largest one. But after that UBCM breaks with both “major” (in size they are rank 8 and 18 among BC CMA/CAs, respectively) and “census metropolitan area” and includes two census agglomerations, Prince George and Squamish.

So why then were these census agglomerations added to this graph? What they lack in being “major” they make up for by having a large difference between population and dwelling growth (rank 4 and 1, respectively, with Dawson Creek (in a twisted way where both population and dwelling growth were negative) and Quesnel taking spots 2 and 3). In other words, this graph is the result of cherry picking, not of data analysis. And cherry-picking is unfortunately, and to much embarrassment for UCBM, a theme in the report.

But let’s ignore this for now and check what’s going on with Squamish, the CMA/CA with the largest difference between population and dwelling growth in BC. Squamish is also interesting for other reasons, it abuts BC’s largest CMA (Vancouver) and it’s (private) dwelling stock grew by an astonishing 30%, almost double that of the second (Kelowna) and triple of the third (Chilliwack) and far outpacing Victoria and Vancouver who rank 7th and 10th in dwelling growth among BC’s CMA/CAs.

Before we get started, we should remember that comparing population to dwelling growth does not tell us much about whether this is a problem or not, this stat is more a hallmark of shallow data BS than analysis. These two stats can diverge for three main of reasons, change in household size, change in dwellings not occupied by usual residents, and change in population not in private dwellings. This last one is simply a result of a mismatch of units. Population is comprised of population in private dwellings plus the population in collective dwellings, but we should only compare the population in private dwellings to the private dwelling stock, not the total population. The population in collective dwellings is typically quite small and for larger regions like a CMA or CA this last factor won’t matter much (though it can matter quite a bit on the local level, especially around, e.g. universities). Data on the population in private dwellings in 2021 is not yet available, but we can start to get a glimpse of the other two factors.

Declining household sizes is a long-standing trend in Canada and across almost all countries, and it naturally leads to dwelling growth outstripping population growth. This means that just to keep the population stable we need to add housing, and in areas that don’t add (much) housing, for example much of the West Side of the City of Vancouver, the population generally declines. Unless we want to draw upon fairly authoritarian policies it is hard to see what can be done about declining household sizes or why this would be seen as a problem.

The remaining issue, an increase in dwellings not occupied by usual residents, could potentially be problematic, so this is worth looking into in detail. An increase in vacancies could indeed indicate “empty housing,” maybe abandoned, maybe used only for seasonal use or short-term rentals, or maybe left empty for other reasons.

To understand how population and dwelling change relates our interactive Canada-wide map of Components of Population Change decomposes the change in population for each region into three components: change in population due to change in dwelling units, change of population due to change in household size, and change of population due to change in dwellings not occupied by usual residents. Looking at Squamish we see that the population changed by 30.3% due to the change in dwellings (matching the dwelling growth by definition), but declined by 4.4% due to a decrease in household size and declined by 4.1% due to an increase in dwelling units not occupied by usual residents.

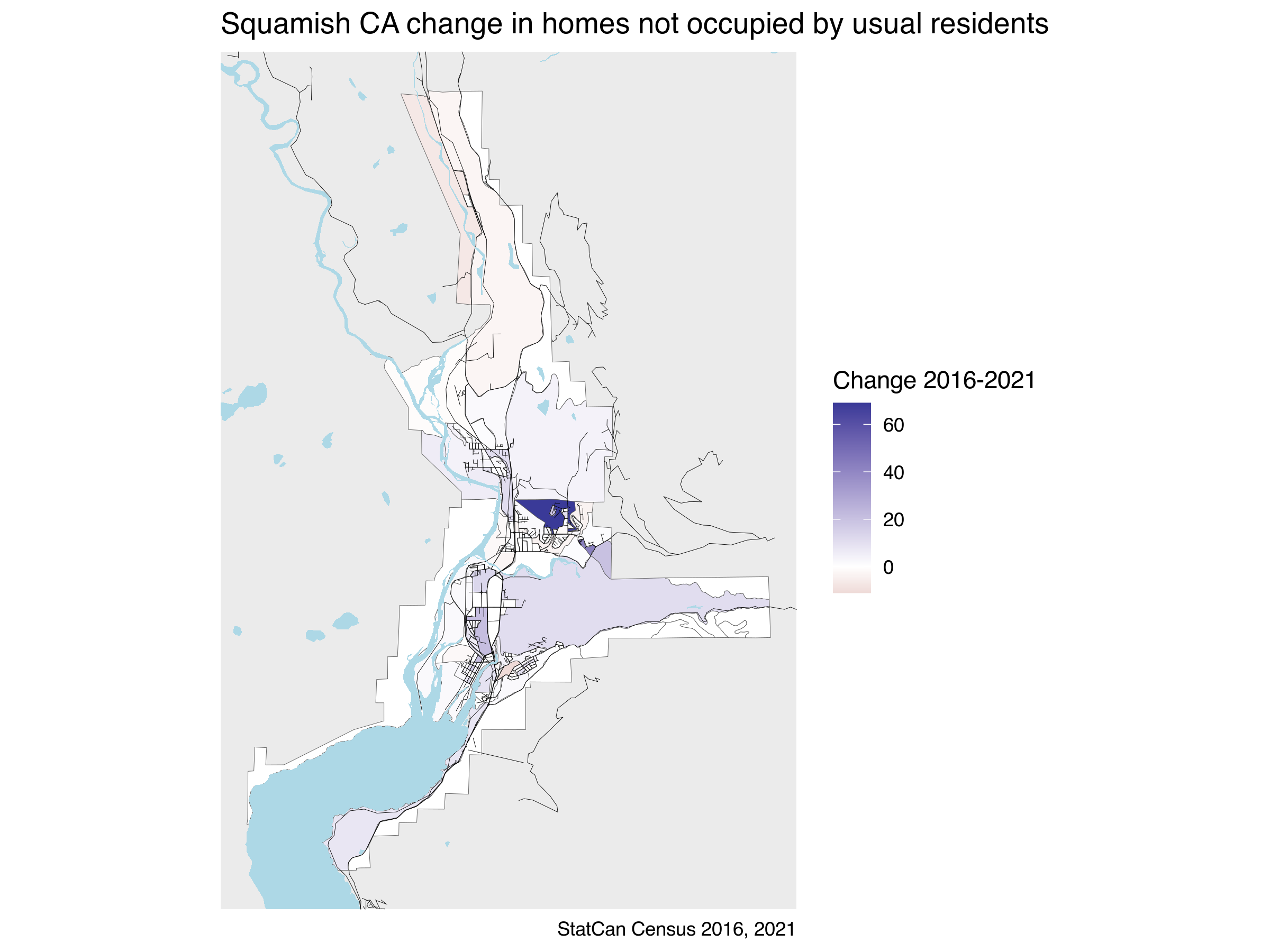

So what’s going on with the dwellings not occupied by usual residents? In Squamish CA it increased from 325 (4% of dwelling units) to 725 (7% of dwelling units).

Let’s take a look at the change in number of homes not occupied by usual residents at fine geographies based on dissemination blocks to understand where they are and get an idea of what is going on there.

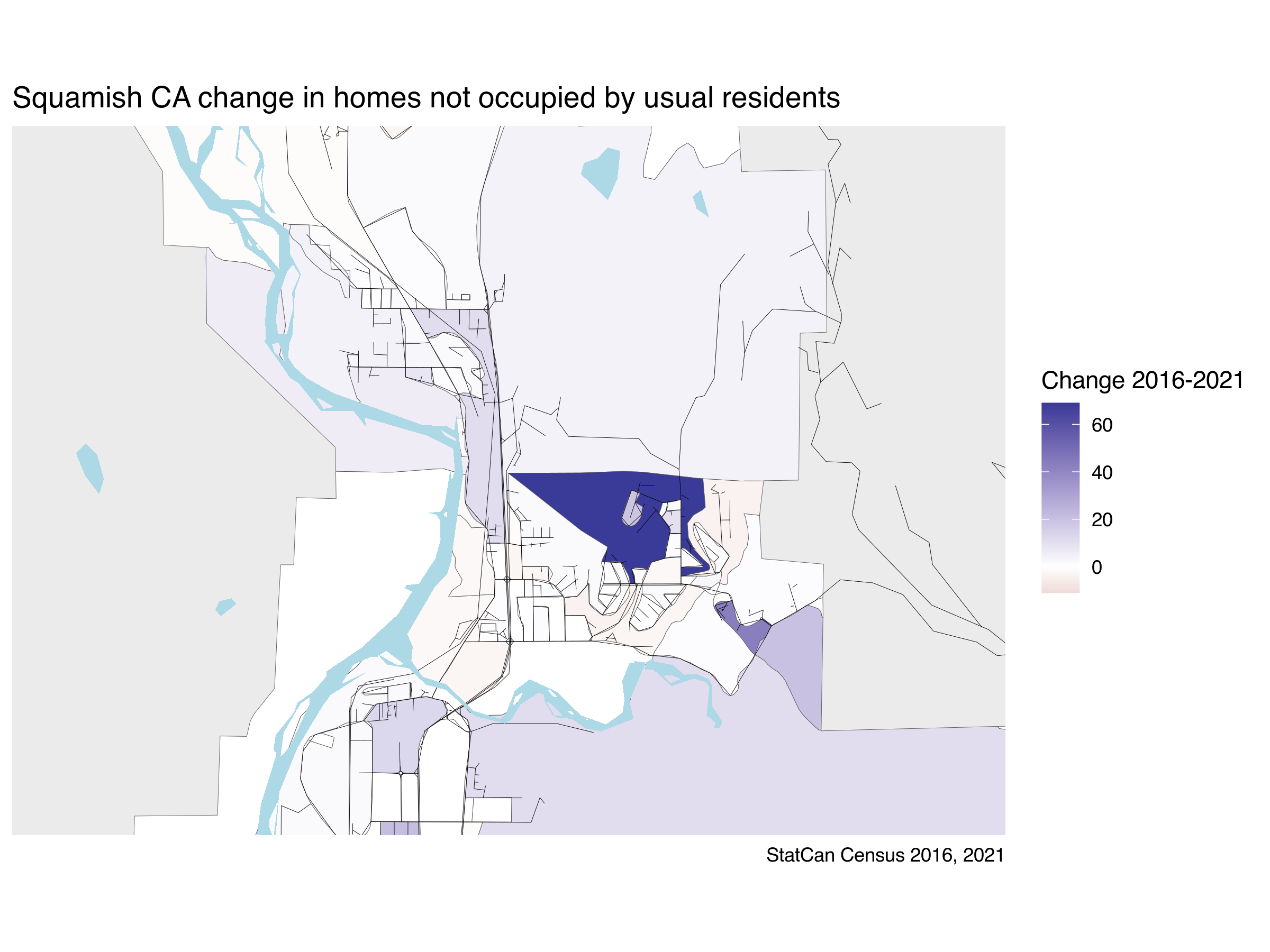

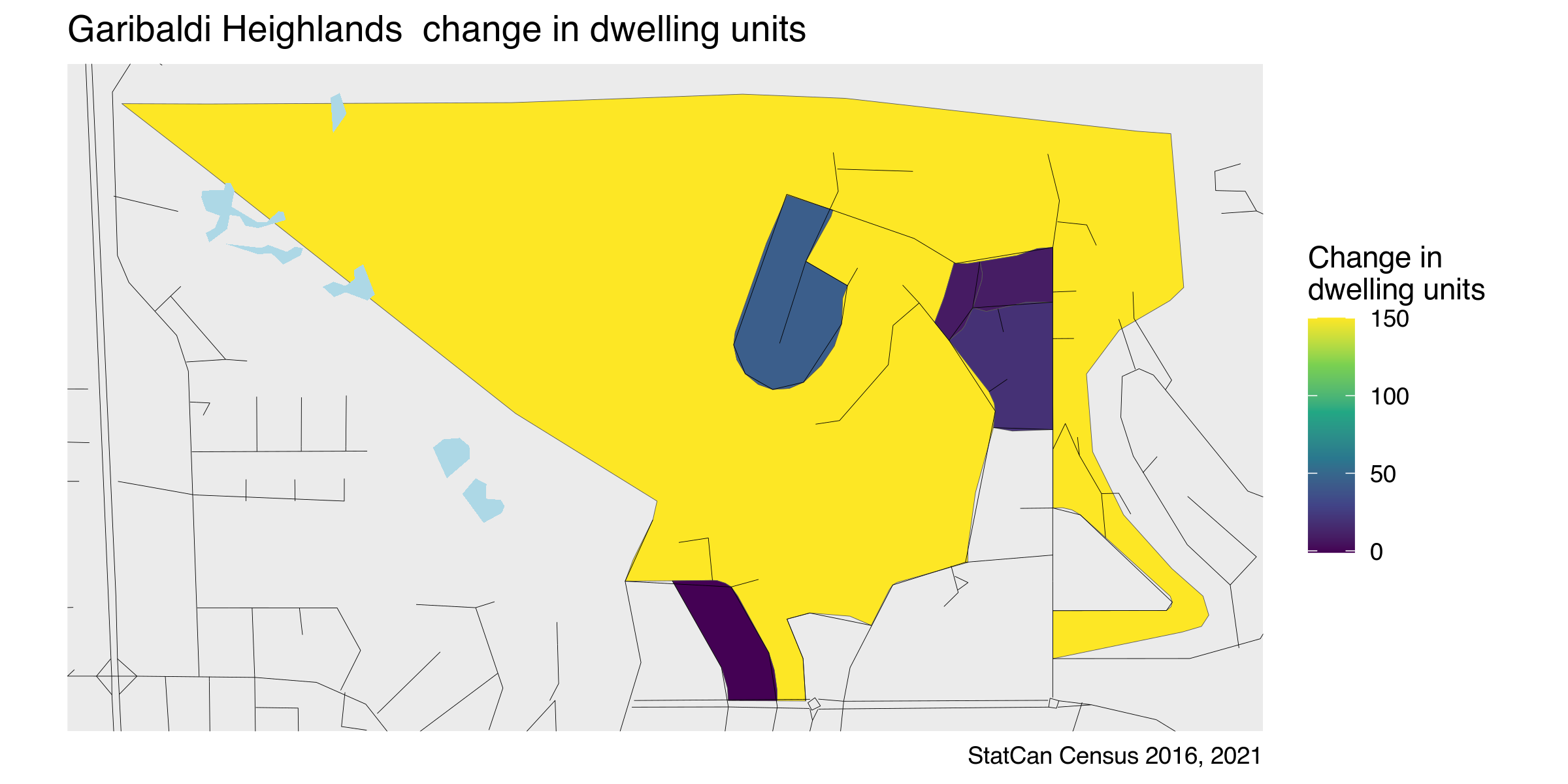

Most blocks saw small increases, some saw small decreases, but one particular area saw large increases in dwellings not occupied by usual residents. Let’s zoom in for a better view.

The change seems concentrated in area in the northeast portion of Garibaldi Highlands, an area built up before 2016, this change is not due to new construction like we have seen in parts of Vancouver with large change in the number of dwellings not occupied by usual residents. Scrolling through the area in Google Street View it does not look particularly “empty”. It’s mostly single family homes.

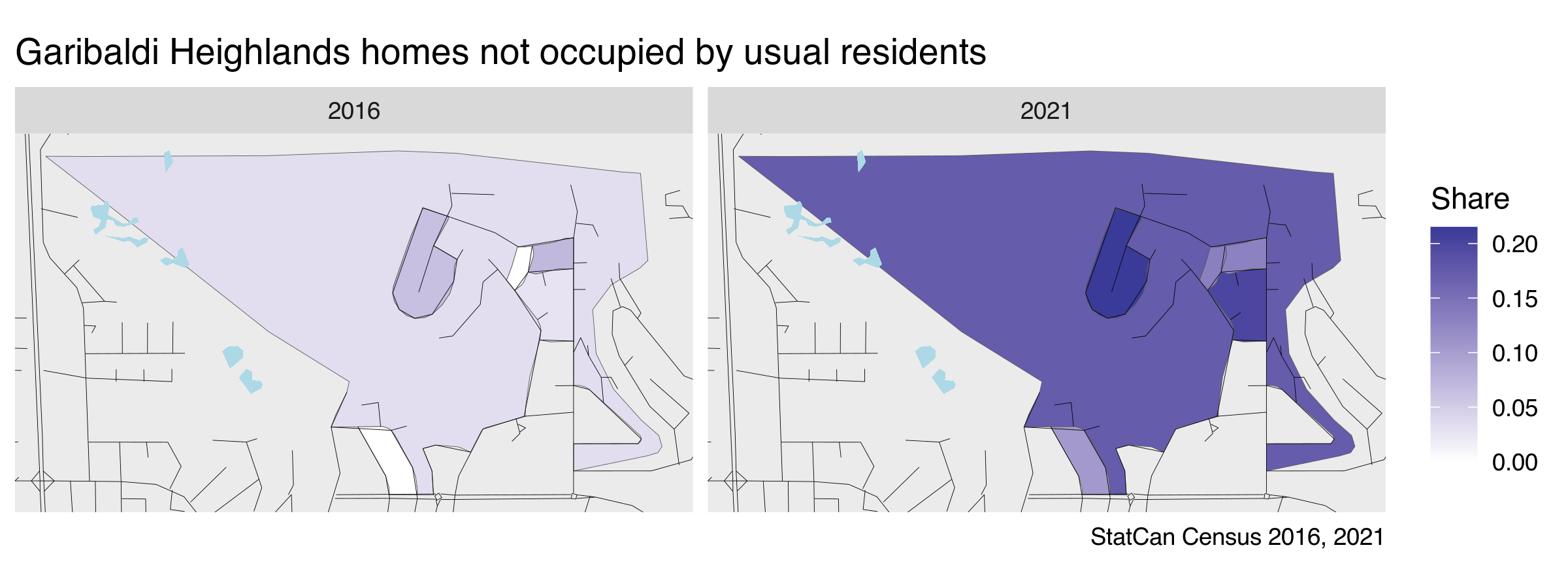

Picking out the worst offenders in the region, here is a side by side comparison of the share of dwelling units not occupied by usual residents.

But there is something else funny going on, this area gained a lot of dwelling units without construction to account for this.

This looks like a reclassification issue, similar to what we have seen in e.g. the City of Vancouver, and what has tripped up lots of people before who have claimed that we have built enough housing based on sloppy use of census data. What most likely happened in this case is that the Census got better at locating secondary suites in Squamish, resulting in an increase in housing units without new construction. And we know well by now that secondary suites are the form of housing with the highest rates of being “unoccupied”, mostly because owners may choose to not rent them out and keep them for their own use. To confirm this theory we will have to wait until the next census data release when we learn about the structural type of housing to see if there has indeed been a shift away from “single-detached” toward “duplex” housing (the census classifies a single family home with a suite as two “duplex” units).

It’s probably no coincidence that the UBCM report cites a prime example of such misguided analysis, apparently unaware that John Rose’s Housing Supply Myth, Working Paper, Version 1 is deeply flawed to the extent that the conclusions are wrong. Overall, Census users should always read the fine print for methods changes when carrying out comparisons over time, and should also remain mindful that the Census cares a lot more about undercounting people than they do about overcounting dwellings (they primarily keep track of dwellings as a way to find people). As a result, dwelling data should be interpreted with some care.

Upshot

What does the cherry-picked stat about Squamish’s dwelling growth exceeding population growth tell us? Nothing, except once again that the authors of the report don’t understand housing.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to replicate or adapt for their own purposes.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2022-04-26 16:13:39 PDT"## Local: master /Users/jens/Documents/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [ac5107a] 2022-04-05: fix link to github code## R version 4.2.0 (2022-04-22)

## Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Monterey 12.3.1

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/C/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] mountainmathHelpers_0.1.4 tongfen_0.3.5

## [3] cancensus_0.5.0 forcats_0.5.1

## [5] stringr_1.4.0 dplyr_1.0.8

## [7] purrr_0.3.4 readr_2.1.2

## [9] tidyr_1.2.0 tibble_3.1.6

## [11] ggplot2_3.3.5 tidyverse_1.3.1

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] Rcpp_1.0.8.3 lubridate_1.8.0 class_7.3-20 assertthat_0.2.1

## [5] digest_0.6.29 utf8_1.2.2 R6_2.5.1 cellranger_1.1.0

## [9] backports_1.4.1 reprex_2.0.1 e1071_1.7-9 evaluate_0.15

## [13] httr_1.4.2 blogdown_1.9 pillar_1.7.0 rlang_1.0.2

## [17] readxl_1.4.0 rstudioapi_0.13 jquerylib_0.1.4 rmarkdown_2.13

## [21] munsell_0.5.0 proxy_0.4-26 broom_0.8.0 compiler_4.2.0

## [25] modelr_0.1.8 xfun_0.30 pkgconfig_2.0.3 htmltools_0.5.2

## [29] tidyselect_1.1.2 bookdown_0.26 fansi_1.0.3 crayon_1.5.1

## [33] tzdb_0.3.0 dbplyr_2.1.1 withr_2.5.0 sf_1.0-7

## [37] grid_4.2.0 jsonlite_1.8.0 gtable_0.3.0 lifecycle_1.0.1

## [41] DBI_1.1.2 git2r_0.30.1 magrittr_2.0.3 units_0.8-0

## [45] scales_1.2.0 KernSmooth_2.23-20 cli_3.3.0 stringi_1.7.6

## [49] fs_1.5.2 xml2_1.3.3 bslib_0.3.1 ellipsis_0.3.2

## [53] generics_0.1.2 vctrs_0.4.1 tools_4.2.0 glue_1.6.2

## [57] hms_1.1.1 fastmap_1.1.0 yaml_2.3.5 colorspace_2.0-3

## [61] classInt_0.4-3 rvest_1.0.2 knitr_1.38 haven_2.5.0

## [65] sass_0.4.1Reuse

Citation

@misc{what-s-up-with-squamish.2022,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {What’s up with {Squamish?}},

date = {2022-03-30},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2022-03-29-what-s-up-with-squamish/},

langid = {en}

}