(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

In this post, we take a moment to appreciate the first housing policy announcements from BC’s new Premier, offered up just days into his term. David Eby comes to the post fresh from his joint roles as Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Housing. In these roles, he was central to fashioning the teeth behind BC’s housing policy. Initially these teeth were directed at the private sector, with a special focus on rooting out the “toxic demand” thought to be leaving too many dwellings empty. The Speculation and Vacancy Tax (SVT) remains the most visible legacy of this approach, as we’ve written about before and we provide a brief update of SVT results based upon the latest release in our appendix below. But other legacies include things like BC’s beneficial ownership registry, insuring better transparency for private corporations.

It hasn’t all been teeth, though. Under the NDP, BC has also invested more heavily in social and affordable housing, with the party more than doubling the budget of BC Housing as public agency since taking over in 2017. These investments in social and affordable housing have directly contributed to improving peoples’ lives and we’d join those arguing that we’re still not building enough. But even here, the teeth came out when it came to the corporate side, largely directed at BC Housing’s operation as a Crown Corporation, as in this past July’s snap announcement that a new board would be taking over.

This week’s announcement doubles down on teeth. But Eby’s found a new target in municipal and strata corporations (i.e. condominium).

These two kinds of corporations are, in many respects, more similar than not. Both afford expansive local powers over land, development, property use, and servicing. Both are established via legislation as “creatures of provincial governments” (as Eby argued directly in a recent case in otherwise unlikely support of Doug Ford’s powers in Ontario). But strata corporations are generally nested within municipal corporations, and a key difference between the two has been in governance structure and exclusions carved out from Human Rights Codes. In particular, renters don’t get to vote in strata, unlike in municipalities. Renters could also be excluded by strata corporations entirely (via rental restriction bylaws). And strata could also put in place age restrictions on residents (unlike cities). As for municipal corporations, their means of exclusion remain more limited than strata corporations, though the scale of their exclusion has wider reach. Municipalities exclude mostly by preventing new housing from being built.

And here’s where the teeth come in. New amendments to the Strata Act rip away existing strata corporation rights to exclude renters and discriminate by age (excepting for explicit retirement communities). Separately, the province is nipping away at municipal corporations’ independence in precisely those places where it’s being used to deny housing.

So can teeth grow housing?

We’re pretty sure that the answer is YES!

But it takes care and skill, because teeth only work to grow housing if they’re deployed against the right targets with the right pressure. Think of a well trained sheepdog nipping its flock into shape. Let’s take a closer look at what the new announcements portend in this regard, splitting out the strata corporation and municipal corporation parts separately.

Strata rental restrictions

Removing the option for rental restrictions from strata legislation is not aimed at growing new housing so much as adding currently (mostly) empty housing back to the market for habitation. In this way it’s most similar to the Speculation and Vacancy Tax, which aimed at the same target. Of note: rental restriction exemptions from the SVT also no longer apply as of 2022. This raises three questions.

- How many properties are affected by this legislative change?

- How many properties can we expect to get added to the occupied housing stock?

- Would these properties have ended up there anyway?

In answer to the first question, the premier cited a number of 300k strata units with rental restrictions that this law could apply to, but this is likely a substantial over-estimate. It appears that this is simply the number of strata units with plans registered before January 1st 2010. That’s when the law changed so developers could exempt new strata from rental restrictions over the long term regardless of whether strata councils attempted to pass such restrictions. Many developers did so, reducing the prevalence of rental restrictions past this point, but not (contra the impression from the provincial press conference), banning such restrictions. On the flipside, there are also many older strata corporations that don’t have rental restrictions, and for those that do there are a broad range of models for how they apply and how binding they are. Some strata corporations ban all rentals, others allow only a limited number or share of properties to be rented out, some allow up to half of strata lots being rented. The legislation will impact strata corporations with different types of rental restrictions to a different degree.

This makes it difficult to give a precise answer to the first question. But the second one might be a bit easier.

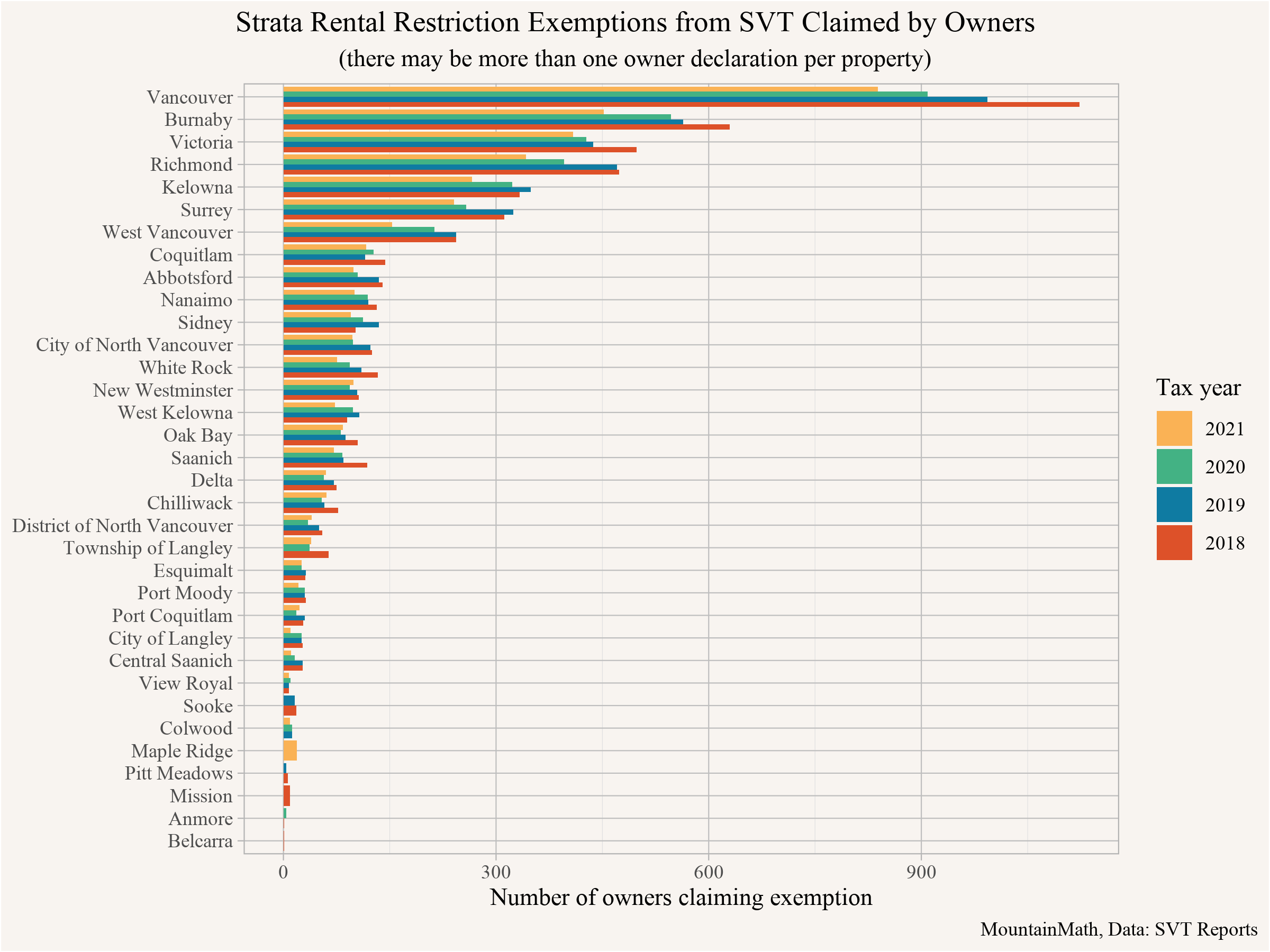

At least for the regions covered by the SVT we know how many strata units have been claiming the exemption from the tax due to strata rental restrictions, giving a proxy estimate of how many units are being held off the market because of these rules. It’s only a proxy insofar as claimed exemptions don’t necessarily reflect the underlying logic or situations of landlords; often it just comes down to which exemption is easiest to claim. In the press release and conference the premier noted that approximately 2,900 strata units claimed the rental restriction exemption in the SVT regions in 2021, the last year in which it was available. This appears to roughly match SVT technical report counts, except that there exemptions are reported in terms of the number of owners claiming the exemption rather than properties. Latest revised counts for 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 came in at 5,591, 5,194, 4,661, and 4.081 owners, respectively, showing a gradual decline in those taking the rental restriction exemption since the SVT began. It’s quite reasonable that the most recent figure equates to 2,900 strata units, as reported by Eby, if enough owners laid claim to the same properties.

Drawing upon the latest report (just released after Eby’s press conference!) we can also check how rental restriction exemptions have been distributed spatially. Again, we draw upon owners claiming rental restrictions rather than strata units.

Here we see most reporting municipalities have already witnessed a decline in units claiming the rental restriction exemption. But this data only covers the SVT regions. Of course, this is also where most strata condominium properties are located. We can use 2021 census data to estimate that roughly 87% of BC condo units are in the SVT area. It would be better to use BC Assessment data for estimates like this, but unfortunately our province keeps BC housing data locked up in order to be able to sell it (we’ll return to our pitch for more open data below). Overall we would expect somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000 rental units might get freed up were rental restricted units returned to the market. Probably closer to 3,000. That’s equivalent to a one-time supply shock of less than 10% of annual completions. Not nothing, and every bit helps, but on it’s own this will do little to get us to where we need to be with CMHC analysis suggesting we need to more than double housing completions over the next ten years to catch up on our housing deficit.

But were changes to the Strata Act necessary to bring these units back to the market, or would they have gone there anyway given the removal of the rental restriction exemption to the SVT in effect as of this year? This remains a good question. Certainly the removal of the rental restriction exemption within the SVT and the removal of strata rights to restrict rents can be expected to work together more smoothly now. Applying teeth to strata complement the teeth already applied to property owners, providing the latter with new options to rent out their units rather than paying the tax instead of just selling or moving in themselves. This makes sense from a policy perspective, lessening the impact of the SVT change on those most affected. But it’s hard to separate out how many units are likely to become newly occupied from the Strata Act change from how many units were already likely to shift into occupation due to the SVT change.

Even if it doesn’t do a lot for supply, lifting rental restrictions in strata can still help a lot of renters, especially those caught between strata rules and landlord attempts to evade them. This should lead to greater renter security and (hopefully) less renter stigma, and we applaud Eby for this move, bringing BC’s policies more in line with places like Australia’s, where rental restrictions have long been disallowed within strata (more on comparative strata law here). Yet renters in condominium are still likely to remain second class citizens. They still won’t get to vote or have much of a say within the “fourth level of government” administered by the strata corporation.

Age restrictions

The other part of the legislative changes addresses age restrictions. This probably won’t change the total number of units available, but it does address the question of how these units can be occupied. As our past research demonstrates via audit study, discrimination against children is a regular feature of the rental market. Mostly this is illegal, running against BC’s Human Rights Code. But as Doug Harris explained in a recent talk, BC is the only province in Canada enabling age restrictions in strata other than for senior housing, and there are questions around how this fits in with broader anti-discrimination rules in Canada. This was not addressed in the last overhaul of the condominium law which BC used to further clarify exactly how condo can discriminate against children and young adults, but it’s good to see the teeth of the province finally cutting away the ability for strata to engage in these discriminatory practices.

Nipping Municipalities into Shape

What about municipalities? Here’s where we see the most potential for teeth to grow housing.

As our work on metropolitan zoning practices has amply demonstrated, municipalities have used the powers given to them by the province to tightly regulate the addition of new housing. Through rules attached to lots, municipalities narrowly circumscribe the locations in which new multi-unit housing can be added and prevent the subdivision of lots enabling more single-family housing. As a result, in many of our municipalities it often takes years of negotiations and approval processes to add new housing. Overall this makes it more expensive to construct housing and reduces the amount that gets built. Moreover, municipalities don’t seem to be fully aware of their role in our provincial housing shortage.

As it stands, the province has not yet committed to reforming municipal powers. Instead in 2019 the province began requiring municipalities to author Housing Needs reports, estimating how much new housing of what type was required to meet projected future needs. But the province did not require municipalities to adhere to common estimation standards or pre-zone for this new housing. Enter the newly announced “Housing Supply Act,” adding teeth to both Housing Needs reporting and its implications. Assuming it is enacted, the province will begin the process of auditing needs reports (choosing 8-10 recalcitrant municipalities) and working directly with municipal governments to insure the housing needed gets built, including by order-in-council, overriding municipal exclusion powers where necessary.

Is this all bark and no bite? So far, yes. BUT… there’s a promise of a bite to come, and that might be enough for a skilled sheepdog to bring our flock of wayward municipalities to order. In the short term, there’s a hope that municipalities will begin planning for and approving more housing so as to avoid making “the list” of 8-10 municipalities at risk of having their control over development stripped away by the province. No one wants to be the example made to others. We see this as all to the good.

In the long term, as the province chooses its examples it will become forced to work through its own definitions of how to understand housing need and translate that need into development objectives. This is going to be hard and risky work. Even by itself, estimating housing need is really hard, as explained in a good piece in the Atlantic the other day. We have explained the complications associated with modelling housing demand in detail before, and highlighted how misspecifications of housing demand models by regional planners have systematically enabled the buildup of our housing shortage. We’ve also made a start at estimating aspects of housing need, like suppressed household formation. CMHC has also done some work on this front by providing estimates of the provincial supply gap and projecting what needs to be done to close our current gaps by 2030. But housing is inherently local, and work is underway to provide metro level supply gap estimates.

The province has indicated that they are looking for municipal level targets as it is municipalities that engage in the rationing of housing. But the province has not explained how these municipal level targets are linked. Right now municipalities create housing needs reports in isolation, but that’s not how housing works. When only modelling individual municipalities, the province won’t be able to distinguish if e.g. housing demand in Lion’s Bay is high because people want to live in that location, or if that’s only the fallback choice because West Vancouver failed to build housing. Going either by methodology prescribed by the province for their current municipal housing needs reports, or the news reporting on the proposed evaluation of municipal targets it looks like the province still has a ways to go in understanding how to model demand for housing. The current methodology does not adequately deal with suppressed household formation or changed in and out migration due to housing pressures, and they fail to recognize the role of rising incomes on housing consumption. As such they are bound to systematically under-estimate housing demand.

Alternatives to rationing housing

It’s important to note that the provincial approach is still grounded in our current planning regime built around rationing housing at the municipal level. Even the new provincial teeth are only nipping at the edges here, intervening via housing targets to prevent excessive rationing but not otherwise yet departing from the shape of existing practice. Policy is path-dependent, and given where we are this may be a defensible approach. But it’s worth pointing out alternative approaches. One approach would be to require municipalities to provide ample outright zoning to allow for organic housing growth. This could also be combined with overriding restrictive zoning, especially near central areas with provincially funded transit infrastructure. Effectively these kind of moves would follow the New Zealand approach, which is showing very encouraging first results both in terms of increase in housing production as well as effects on rents.

In his leadership race Eby did suggest to allow at a minimum for three (strata) units outright on every lot in “urban centres” in BC. There has been no policy brought forward to implement this (yet), but this would be a small step toward breaking out of the rationing regimen and allowing housing to grow via outright zoning. This falls short of what New Zealand implemented but does follow their direction.

In many urban municipalities enabling three units per lot outright would constitute a significant bump in allowable density, although cities could easily make it unviable through parking requirements or other zoning constraints. The City of Vancouver already technically allows three (or four) units per lot, but Eby’s proposal to allow strata dramatically changes how these properties could get used. To realize this density currently the City of Vancouver is asking an owner-investor family to take on a larger mortgage than what’s required for their family and also take on two rental properties on their lot and operate them as landlords. This incentivizes high debt levels and coerces people into becoming landlords. Over the years as the family pays down their mortgage and their income rises they often choose to stop renting out their suite, leading to suites being the most empty form of housing in Vancouver. The proposal by Eby would change this by allowing to stratify the property, with the family buying as much housing as they need and taking on a lower mortgage instead of relying on a secondary suite or laneway house as a “mortgage helper”. After all, the best mortgage helper is a lower mortgage. Moreover, the other units would now be separate taxable dwelling units, and thus subject to other regulations like the Empty Homes Tax and the Speculation and Vacancy Tax, and there are currently a lot more unoccupied suites than there are strata properties that sit empty because of rental restrictions.

We hope the proposal on allowing 3 units outright will come, and that it gets expanded on. In central cities like Vancouver we have already been discussing allowing 6 units per lot, with some parties campaigning on allowing lowrise apartments everywhere, which is more in line with the demand for housing in amenity and jobs rich Vancouver. New Zealand and California have tied some of their rules to their frequent transit network, some years back we have looked at where development within the frequent transit network should go if minimizing renter displacement were a policy objective (it should be!). Tackling BC’s housing shortage requires ambitious action. Our new Premier is off to a good start, but we hope he doesn’t stop now. And we’ll keep pointing toward New Zealand as a good place to go for policy innovation!

Less Toothy Housing Policy

All and all, we’re happy to see our new premier adding more teeth to BC’s housing policies, especially insofar as those teeth keep nipping away at the exclusionary powers of strata corporations and municipal corporations. We’d also like more non-toothy policies, including the long promised Renter’s Rebate and more support for building out the non-profit sector (which may be coming). When asked Eby did indicate that he had not forgotten about the renter’s rebate, but there is no timeline for when it will arrive. As a reminder, this was initially envisioned to equalize the homeowner grant that most homeowners enjoy, and provide a small step toward tenure neutrality and undoing the enormous imbalance in benefits higher levels of government bestow upon owners, most notably non-taxation of imputed rent and non-taxation of principal residence capital gains. But if designed right so it also collects information about rental accommodation and rents it could also provide an invaluable source of information on the rental market, as well as an enforcement mechanism (teeth!) for the Residential Tenancy Act in the hard to regulate secondary rental market, which we know is the segment where most evictions in Canada occur. As for an increased build-out of non-profit housing, it may also have to be accompanied by provincial overrides of municipal powers to block housing. So we’ll need the teeth even here.

A new Ministry of Housing

Another announcement was the creation of a dedicated standalone ministry of housing, a role that previously was passed around as something closer to a side-job. We believe this is a positive development, housing is important to the wellbeing of the people in British Columbia, as well as the overall economy. And housing is complex, having a dedicated minister and staff should help create the expertise and knowledge within the government needed to insure it’s forming good policy and promoting that policy in an accurate manner to the public at large.

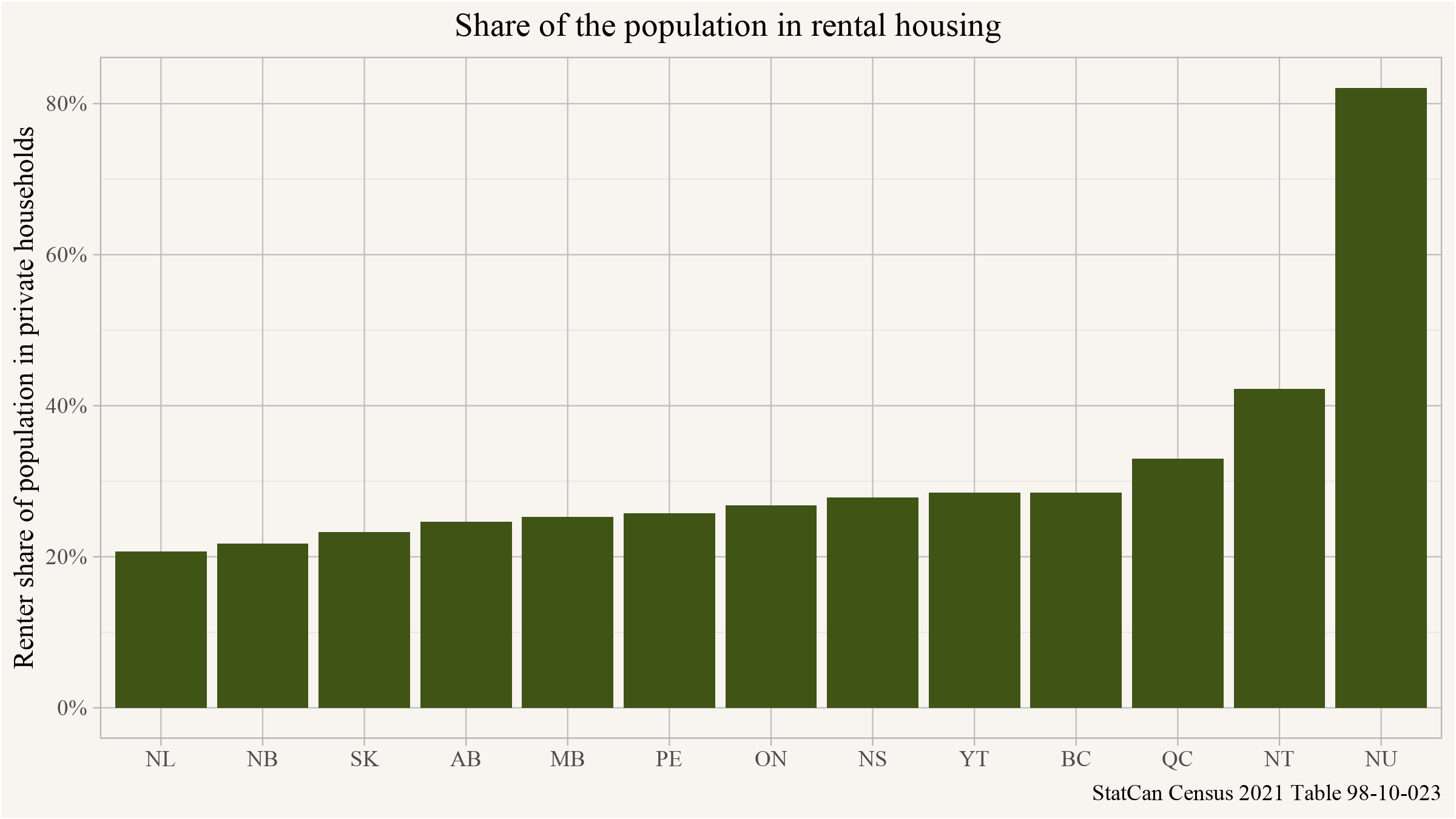

Here we definitely see room for improvement. Not just when it comes to some of the issues already outlined above. It’s important for ministers to get simple things right, like the the unfortunate claim that “BC has more renters per capita than any part of Canada.” Which is obviously (to anyone who spent any time looking at housing across Canada) false no matter how one slices the data. Here is a simple graph of the share of the population in renter households across Canadian provinces and territories.

At this point we want to reiterate that we view data transparency and open data for housing (and other data) as extremely important. Current BC policies, while in principle making data available for researchers, impose significant friction that slow down and stymie housing research, and selling the data to private interests creates an information asymmetry with respect to the public as well as municipalities and governments without the same resources for utilizing the data. That information asymmetry erodes trust and is potentially harmful. We have made this point repeatedly on these pages, and have not lost hope that the BC government will change its mind on the role of housing data, especially during a housing crisis. Another item that a minister of housing might be well-positioned to finally address working with a supportive Premier!

Takeaway

We’re happy to see our new Premier add new teeth to housing policy in the service of better supporting and de-stigmatizing renters within strata and bringing municipal corporations on side with getting more housing built. The province is well-positioned to shepherd its “creatures” - BC’s flock of municipal corporations - to where they need to be to get a lot more housing built. The flurry of changes that have been announces are generally good, but could use more work on the details. And we have high hopes we’ll also see more non-toothy announcements soon, including further direct investments in social and affordable housing.

Thanks for sticking with us. To reward you, here’s a video of some New Zealand sheepdogs at work.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt. This includes code for scraping SVT data out of their PDF reports which is necessary only because of BC broken data practices that default to not making data available but hiding it away in reports, if at all. In a similar vein, this post can’t provide more accurate estimates on strata properties with various forms of rental restrictions because this in part requires access to BC Assessment data which the BC government chooses to continue to keep locked up in order to sell it. (The other important ingredient for these estimates is building on work done by Doug Harris who has researched strata restrictions in BC in great detail.)

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2022-12-17 10:53:41 PST"## Local: master /Users/jens/Documents/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [281f4e5] 2022-11-24: new-premier-new-housing-policy post## R version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31)

## Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Ventura 13.1

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] cmhc_0.2.4 mountainmathHelpers_0.1.4

## [3] cancensus_0.5.5 cansim_0.3.14

## [5] forcats_0.5.1 stringr_1.4.1

## [7] dplyr_1.0.10 purrr_0.3.5

## [9] readr_2.1.3 tidyr_1.2.1

## [11] tibble_3.1.8 ggplot2_3.4.0

## [13] tidyverse_1.3.2

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] lubridate_1.8.0 assertthat_0.2.1 digest_0.6.30

## [4] utf8_1.2.2 R6_2.5.1 cellranger_1.1.0

## [7] backports_1.4.1 reprex_2.0.1 evaluate_0.18

## [10] httr_1.4.4 blogdown_1.10 pillar_1.8.1

## [13] rlang_1.0.6 googlesheets4_1.0.0 readxl_1.4.0

## [16] rstudioapi_0.14 jquerylib_0.1.4 rmarkdown_2.14

## [19] googledrive_2.0.0 munsell_0.5.0 broom_1.0.0

## [22] compiler_4.2.2 modelr_0.1.8 xfun_0.34

## [25] pkgconfig_2.0.3 htmltools_0.5.3 tidyselect_1.2.0

## [28] bookdown_0.27 fansi_1.0.3 crayon_1.5.2

## [31] tzdb_0.3.0 dbplyr_2.2.1 withr_2.5.0

## [34] grid_4.2.2 jsonlite_1.8.4 gtable_0.3.1

## [37] lifecycle_1.0.3 DBI_1.1.3 git2r_0.30.1

## [40] magrittr_2.0.3 scales_1.2.1 cli_3.4.1

## [43] stringi_1.7.8 cachem_1.0.6 fs_1.5.2

## [46] xml2_1.3.3 bslib_0.4.0 ellipsis_0.3.2

## [49] generics_0.1.3 vctrs_0.5.1 tools_4.2.2

## [52] glue_1.6.2 hms_1.1.2 fastmap_1.1.0

## [55] yaml_2.3.6 colorspace_2.0-3 gargle_1.2.0

## [58] rvest_1.0.3 knitr_1.40 haven_2.5.0

## [61] sass_0.4.2APPENDIX

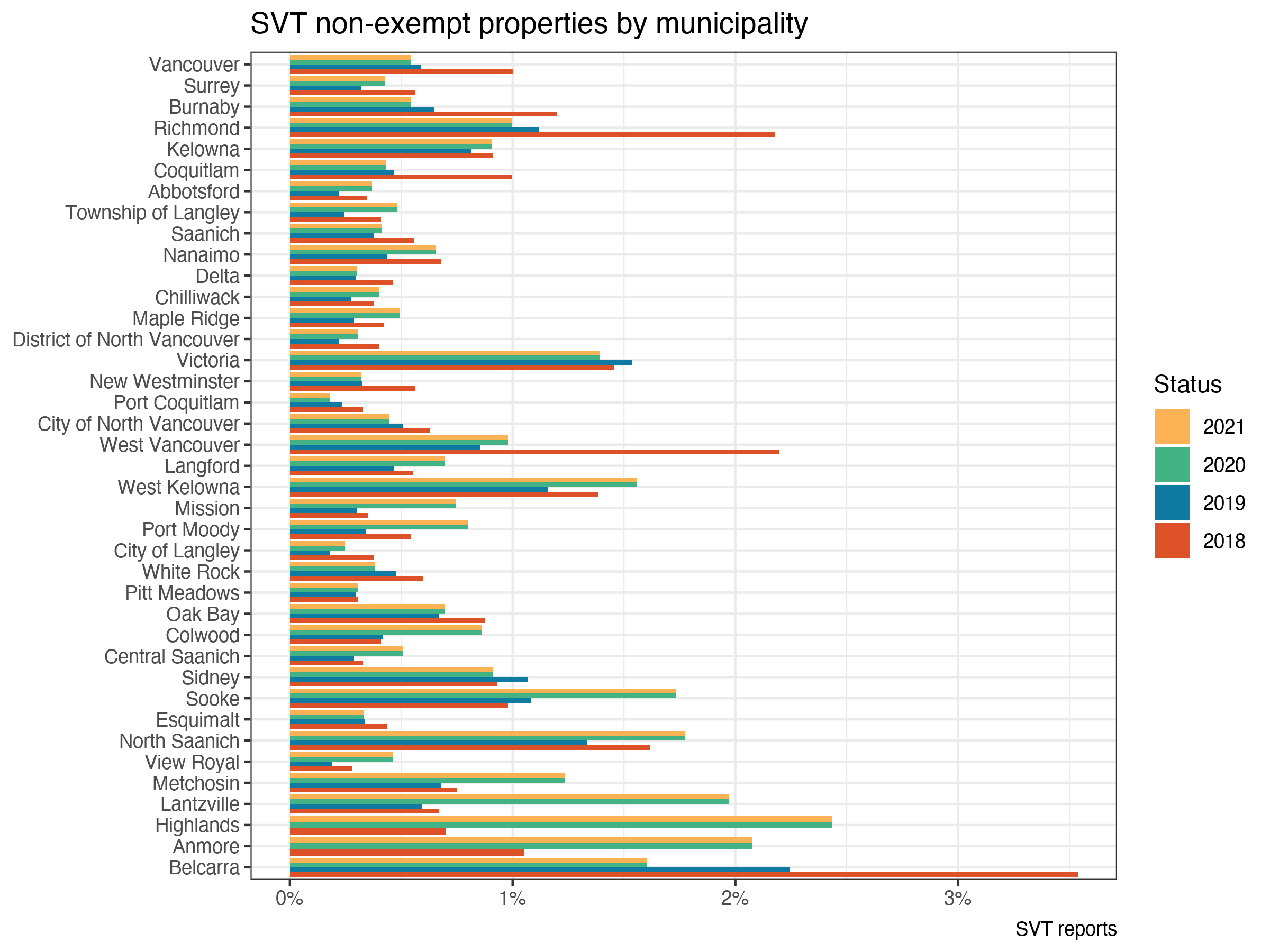

As a final note, we provide a quick update of Speculation and Vacancy Tax results based upon the newest report. Overall little has changed since our last look at three years of data, but more data, more up-to-date, is always better! So here’s a quick summary of where we’re at. The proportion of properties paying the tax continues to decrease, and is now well below 1% across most municipalities. But it was never very high to begin with.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{new-premier-new-housing-policy.2022,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {New {Premier} {New} {Housing} {Policy}},

date = {2022-11-24},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2022-11-24-new-premier-new-housing-policy/},

langid = {en}

}