(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

Say you want to construct some multi-family housing in Vancouver. How long will it take? The answer is simple: it depends. There are many factors upon which it depends. Here we want to highlight one in particular: when you started.

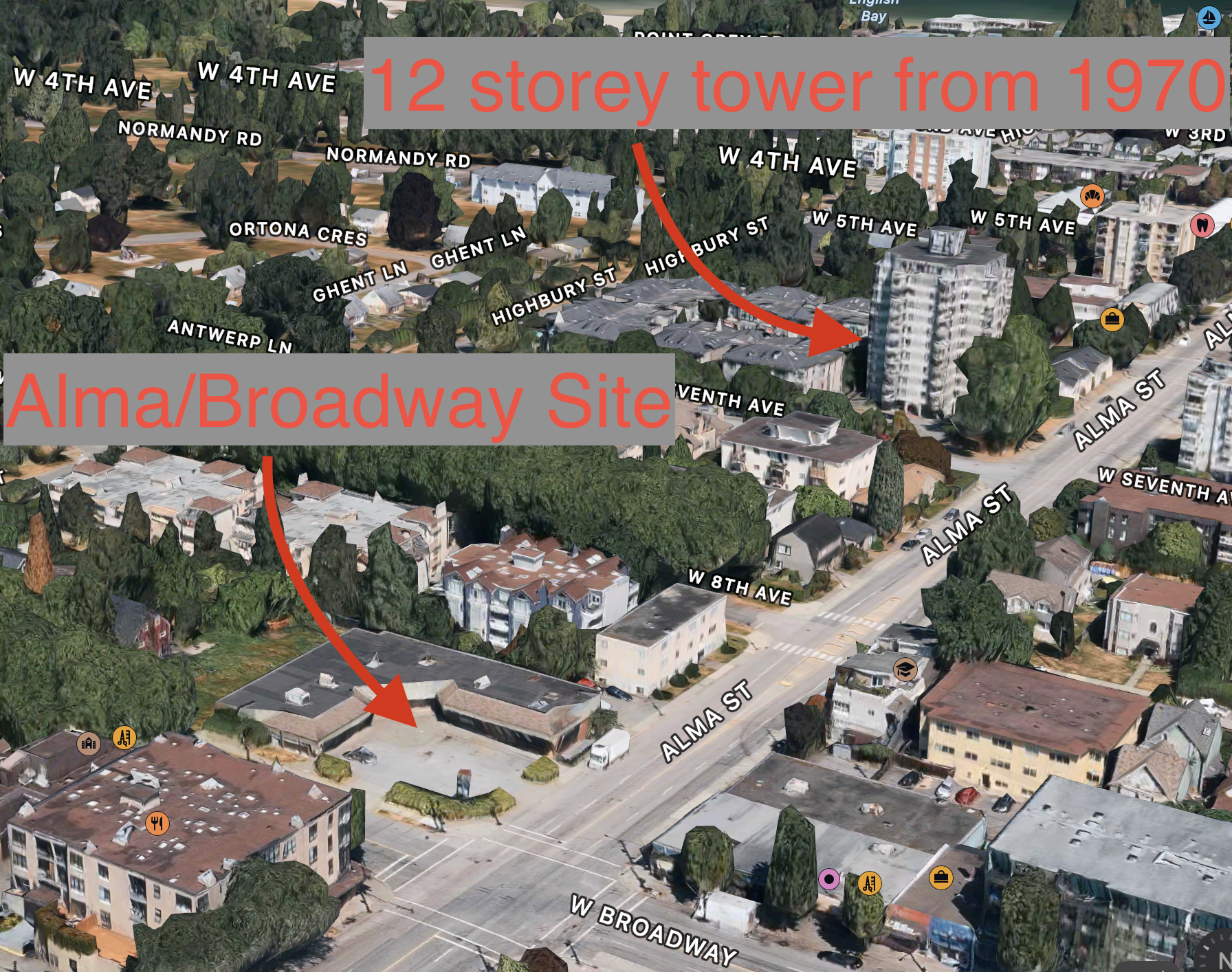

As it turns out, it used to take a lot less time to build multi-family housing. There is reason to believe we could reduce that time again, but getting there involves gathering a better understanding of our current development regime, and placing it in historical perspective. We begin this process below, before diving deeper into two case studies of developments along Alma Street, located very near one another in space, but separated by some fifty years in start time. We’re going to look at the 14 storey rental building currently under construction at the intersection of Alma and Broadway, and the 12 storey rental building built in 1970 two blocks to the north at 3707 W 7th Ave.

But first some history! We’re going to divide time up into three rough regimes, which we call the Permissive Regime, the Zoning for Growth Regime, and the Spot Discretionary Regime.

1886-1931 The Permissive Regime

The City of Vancouver incorporated in 1886, and in its early years its development was relatively concentrated (mostly extending from the old site of Gastown to the East, and from the Railroad’s investments along Granville Street to the West). Bridges enabled leaps across the industrial sites surrounding False Creek, opening up further development to the South. The development regime quickly came under regulation after incorporation, but the form of regulation remained limited, with building permits linked to concerns about fire safety, gradually extending to building codes and the emergence of public health and nuisance regulations just starting to place limits on use (e.g. where a slaughterhouse could locate). Diverse forms of housing, including lots of multi-family, mixed within and beside other building forms and development often followed (and/or paid for the extension of) trolley lines. Early fire insurance maps - and some of the first moving picture footage shot from a trolley - demonstrate the diversity that accompanied Vancouver’s development boom.

Our first development regime began to shift through the 1920s and here we put it to bed by 1931, after a series of preliminary zoning laws were joined to a new plan for the City of Vancouver which, though not fully adopted, would prove enormously influential in ushering in a new, and much stronger regulatory regime. Before we fully got there, 21% of our current building stock was constructed, not counting buildings that got torn down and redeveloped since. To illustrate that legacy, we highlight three examples of pre-1931 buildings below.

What these buildings have in common is that they mix residential and commercial uses. They’ve also stood the test of time and have proven useful to this day, often earning protected heritage designations along the way. But the new, post-zoning regulatory regime made these kind of buildings illegal to construct anew across most of the city. In fact, the first two buildings were rendered illegal to get rebuilt in place under the initial 1931 zoning, and none of these three buildings would be legal to build under their current zoning today.

1931-1972 The Zoning for Growth Regime

The series of zoning laws put in place, starting with their preliminary version in 1927, were adopted largely to prevent the incursion of multi-family apartments into single-family residential districts. But districting into zones also brought other changes, including efforts to more fully separate new development by land use, limiting mixing. Use districts were primarily divided into single-family & duplex residential (RS, RT), multi-family apartment (RM), commercial (C), and industrial (I). Building permits, previously tied to meeting evolving safety and nuisance concerns, became tied to compliance with far more rigid zoning regulations, laying out much narrower lists of allowed uses.

The planner hired to assist Vancouver in its transition to a zoning regime, Harland Bartholomew, also planned ahead, anticipating the future growth of the City. Given extensive surveys of existing uses, Bartholomew imagined the City could accommodate about thirty years of growth under the zoning enacted through the 1920s and 1930s before revisiting its plan. Somewhere around 1960, he thought Vancouver would have to upzone, accommodating a new period of growth.

As it turned out, Vancouver began a modernization of its zoning code in 1956, adopting new zoning district names and guidelines for metrics like Floor Space Ratios that would guide further development, and opening up new opportunities for tower form developments downtown. Through the 1960s, Vancouver would also begin to tentatively expand the range of its multi-family apartment (RM) districts, and also enable towers in these areas, upzoning to accommodate anticipated growth. But a backlash was brewing. A new council would sweep in with the 1972 election under the banner of TEAM, a reformist party opposed to the spread of towers. They placed themselves at odds with the planning regime of the City, downzoned the multifamily apartment districts once more, and ushered in a new regime characterized by much tighter controls on development and more direct negotiation with City Hall.

1972-Present: The Spot Discretionary Regime

The downzoning of residential multifamily (RM) apartment districts helped usher in a new planning and development regime. Its key features included a) the loss of outright development potential on most lots, b) the rise of discretionary development potential with planner approval, and c) the rise of spot zoning through comprehensive development districts with full city council approval.

What we call the Spot Discretionary Regime emphasizes the two processes by which most development of new apartment buildings would proceed. Undeveloped old RM lots, intended to support apartment buildings, continued to see new construction, but generally at much lower heights and density than before and increasingly through discretionary approval processes within existing zoning, where developers had to get approval directly from planners before being able to proceed to getting a building permit. Some new RM lots were also added, expanding a few apartment districts. At the same time discretionary options to add residential units were opened up in other zones. These included, most prominently, the C (Commercial) zones along arterials, but also zones opened up by the rezoning of old industrial lands, especially around False Creek. These highly discretionary comprehensive neighbourhood zones (e.g. FCCDD & FM-1) highlighted evolving priorities of the city. They would effectively transform over time into smaller, lot-specific comprehensive development (CD) zones through a practice known as spot zoning that involved the discretion of both city planners and city council as a whole. The City also began to charge increasing Development Cost Levies (DCLs) for new multi-family apartments, adding Community Amenity Contributions (CACs) for most re-zonings and correspondingly lowering property taxes for existing residents.

The Spot Discretionary Regime has basically continued its evolution up into the present, for the most part progressively layering new rules, procedures, paperwork, and fees onto new multi-family apartment developments. Each of these layers has further oriented developers toward the bureaucracy and politics of City Hall, which have become increasingly important for developers to navigate to get anything built. It’s probably no accident that Vancouver’s housing crisis appears to have grown increasingly dire roughly in accordance with the evolution of the Spot Discretionary Regime. To this the Regime has responded not by loosening its hold over development, but instead by identifying new priorities to enforce through its controls. So it is that the City recently began to prioritize the construction of secured rental apartments, which is how we arrived, for instance, at the Moderate Income Rental Housing Pilot Program (MIRHPP), whereby developers are enabled density bonuses in exchange for building protected and moderately affordable rental apartments instead of condos.

Overall, our different development regimes link to distinct approval processes and paper trails. Our Permissive Regime simply required building permits adhering to relatively simple safety and nuisance guidelines. Our Zoning for Growth Regime required permits to be scrutinized for adherence to relatively strict zoning guidelines, but left a fair number of lots open for outright redevelopment. Our Spot Discretionary Regime saw the closure of most opportunities for outright development of multi-family apartments, shifting developers into often complex negotiations with the City, generally involving either gaining chief planner approval (discretion) or gaining full council approval (spot re-zoning) before moving ahead. The evaluation of lengthening paper trails also involved lengthening approval times and correspondingly lengthening development schedules. As suggested by Ezra Klein’s recent NYTimes column on the Construction Industry, the shift in regimes isn’t unique to Vancouver. But instead of zooming out, let’s zoom in and return to the blocks containing our two nearby tower projects to compare what our Zoning for Growth Regime and our Spot Discretionary Regime look like on the ground!

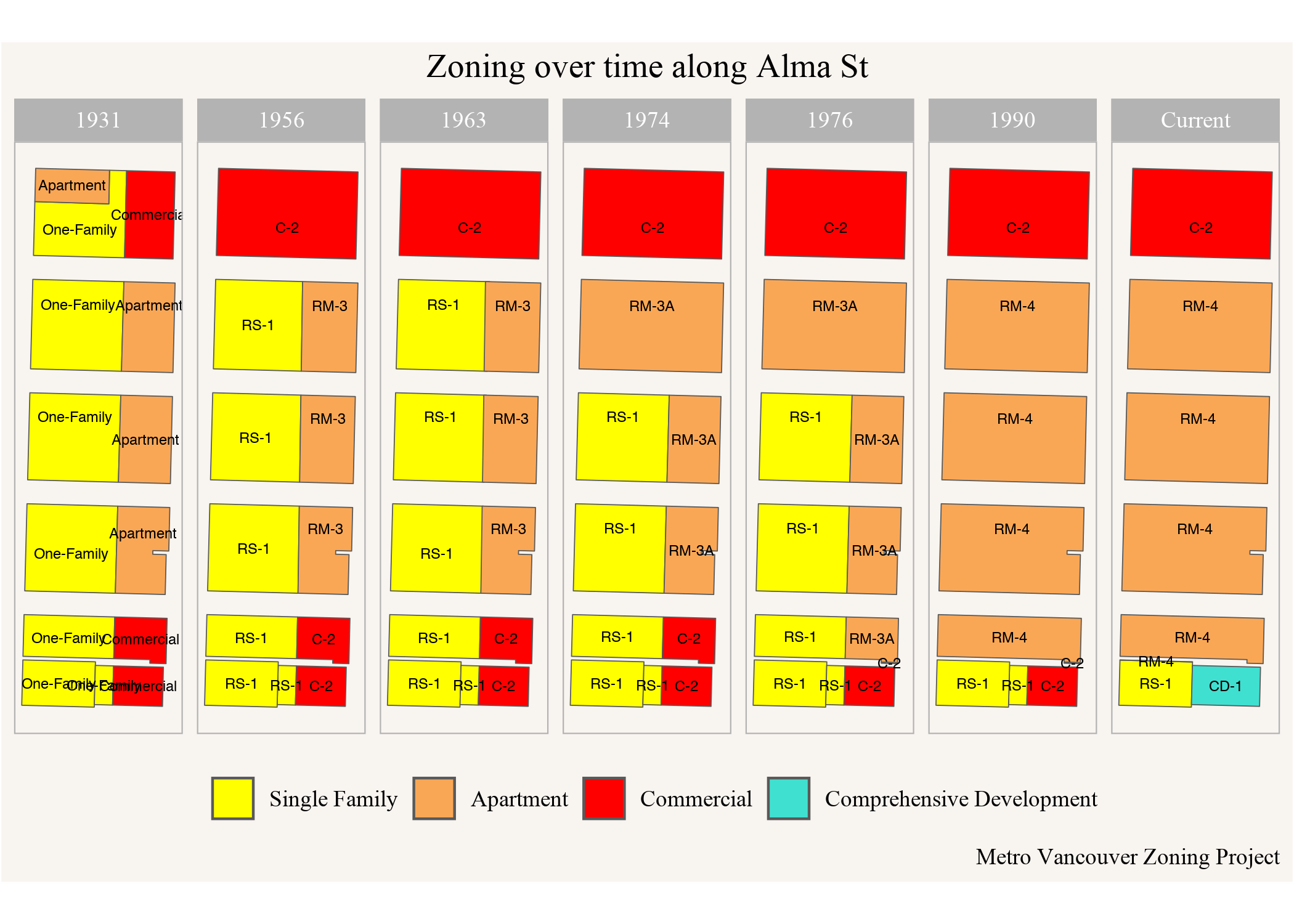

For our case studies, we’re going to zoom in on the miniature Alma corridor between Broadway and 4th Avenue. Let’s have a look at how our regimes have played out via the history of zoning along this corridor. Here we draw heavily from our CMHC-funded project on zoning history.

The area is situated between Broadway to the south (bottom), 4th Avenue to the north (top), Alma St on the east (right), and Highbury on the west (left). West of Highbury Street start the Jericho Lands, which is the site of a future First Nation-led development by the MST development corporation, a collaboration between the Musqueam Indian Band, Squamish Nation and Tsleil-Waututh Nation.

During our Permissive Regime, the Alma corridor remained relatively undeveloped, located on the outskirts at the border between the old City of Vancouver and the former self-styled residential municipality of Point Grey. Correspondingly very little remains from this era.

The amalgamation of Vancouver and Point Grey roughly coincided with the transition into our Zoning for Growth Regime. By 1931, Commercial hubs were zoned for Alma’s intersections with 4th and Broadway with a line of Apartment zoning between the two. The 1956 modernization of the zoning code (Bylaw 3575) replaced these with new C-2 (Commercial) and RM-3 (“Medium Density” Residential Multifamily) zones, installing restrictive RS (Single-Family) zones in the surrounding lots. At that time RM-3 allowed for a maximum height of 40ft and 1.3 FSR. But on July 4, 1961 council amended RM-3 zoning with bylaw 3962 to allow for heights up to 100ft and a change to maximum FSR that started out lower (1 FSR) but rewarded small site coverage, large lot area, and underground parking remaining below the building envelope in a formulaic and predictable way ultimately resulting in a significant FSR boost for towers. This zoning change enabled the 12 storey apartment building at 3707 W 7th Avenue to get built under outright zoning, as well as its mid-rise mate a block to the north.

This upzoning amounted to a significant expansion in developable floorspace across the city, leading to a development boom resulting in lots of new towers still standing today. It delineates two phases of the Zoning for Growth Regime: as thirty years of development filled out the initial plan, the modernization and 1960s upzoning “filled up the tank” of development capacity again.

But the towers prompted backlash, the rise of TEAM, and downzoning, setting up the transition to our Spot Discretionary Regime. Bylaw 4757, which came into effect in February 1974, downzoned the Alma corridor’s RM-3 to RM-3A. RM-3A was still a relatively new zone at the time (created in June 1972), containing similar FSR limits to RM-3, but reduced height to 35ft outright, which at the discretion of the Planning Board could be increased to only 40ft. In March 1976 the city introduced the further restrictive RM-3A1 and RM-3B zones and soon after started downzoning RM-3A areas to RM-3A1 or RM-3B while at the same time continuing to downzone remaining RM-3 areas to RM-3A. This process would take several years, catching up to our Alma corridor by December 1977 when it received its further downzone from RM-3A to RM-3B.

The Spot Discretionary Regime would continue to tinker with the RM codes, for instance adding and subtracting discretionary FSR for units earmarked for seniors, until our Alma corridor was transformed into RM-3A1 in January 1988, before the whole zone was renamed as RM-4 in April 1988. This coincided with the expansion of the zone into former RS lots under Gordon Campbell’s somewhat more developer friendly NPA administration, and a couple of low-rise condo developments were added along Highbury. This is where the RM lots show up in our 1990 map, and where they’ve remained basically through the present (The original RM-4 zoning, which covered the West End before it was replaced by RM-4A and then WED zoning, had been phased out in October 1984, and eventually the West End got downzoned to RM-5.) Meanwhile, the C-2 lands were increasingly allowed, at planner discretion, to accommodate residential apartments, as occurred for the lot on the NE corner of 5th & Highbury. Finally, a CD comprehensive development spot rezoning was introduced at the NW corner of Alma & Broadway in 2020, setting up our second development.

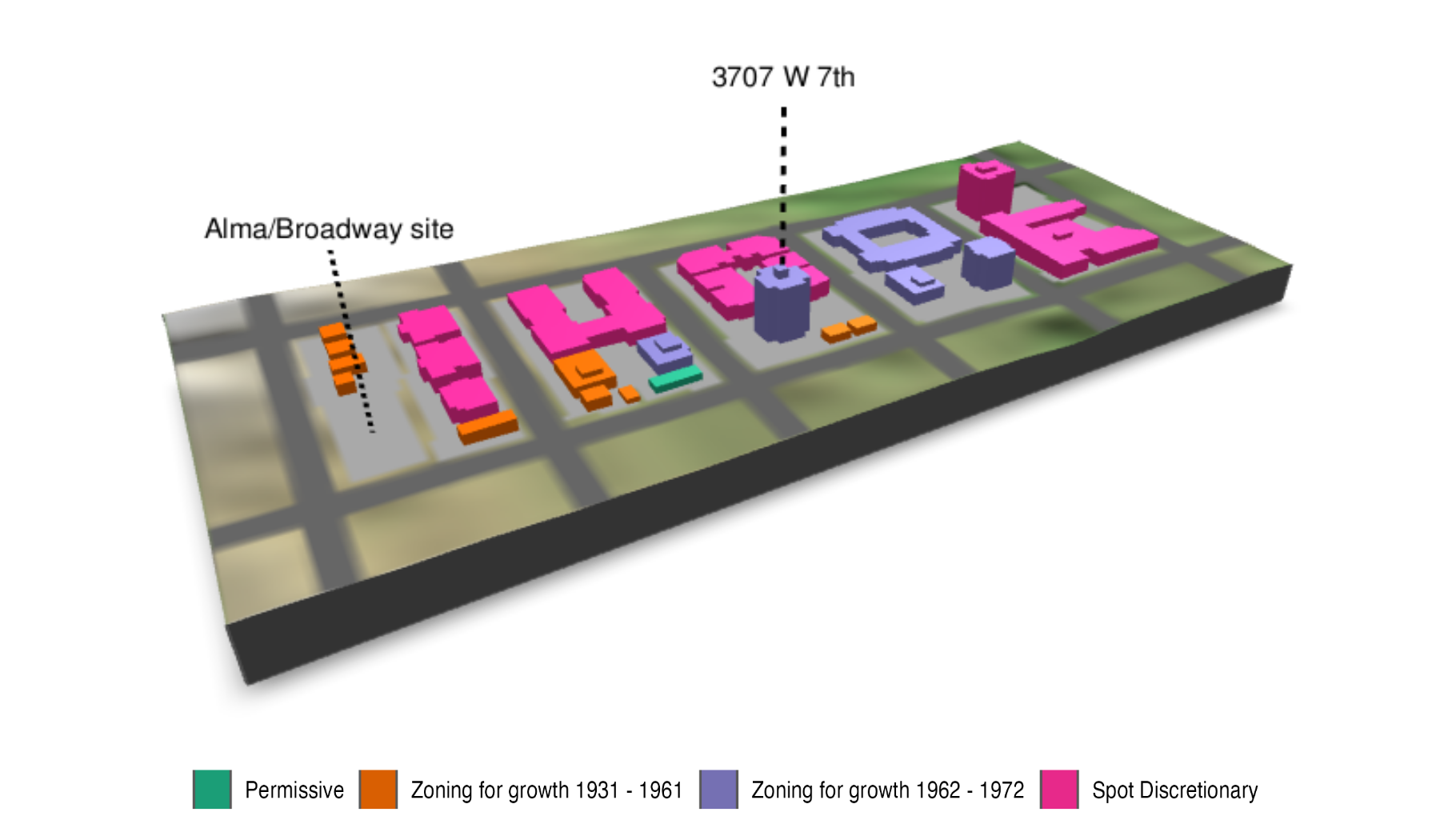

We can see the result today in this 3D view of the two sites we are interested in and the surrounding buildings.

The buildings are coloured by the period when they were built. Only one, in green, survives from the Permissive Regime. Here we divide up our Zoning for Growth Regime into pre-1961 and post-1961, reflecting our interest in the response to the 1961 upzoning. A number of smaller buildings and single family homes survive from before 1961, coloured in orange. Many more were produced after the upzoning, including towers laid out in purple. But not everything in RM came up towers during the 1961-1972 era; notice the multiple low-rise buildings along our strip. Nevertheless, nothing in RM was built to the tower form after the 1972 downzone. Indeed, not much got built at all for quite a while, with a flurry of buildings getting added between 1988 and 1990, including the new low-rise in lands rezoned from RS to RM and the C-2 zoned Jericho Centre and neighbouring condo building (which also benefited from a density transfer).

A Tale of two Towers

So let’s compare our two focus tower developments, the 1970 12-storey rental apartment on 7th and Alma and the currently under construction 14 storey MIRHPP at Broadway and Alma!

3707 W 7th Avenue

Here we have a 12 storey purpose-built rental apartment building, including some 86 apartments. This is just the kind of building that our MHRIPP policy is now meant to promote, constructed some fifty years ago. Of note, even then it could have been constructed as a condo building, though BC’s Strata Act was still relatively new at the time. We don’t know how long it took to pull together the financing for this building, but we do know that it was allowed as an outright use within the zoning code, requiring relatively little in the way of paperwork or discretionary review.

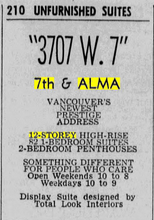

So how long did it take to build?  The city archives date the building permit for it to October 1969 for 86 units, with permit value of $635k. The building completed only about one year later, around which time it got advertised in the newspapers, as in this excerpt from the Vancouver Sun from October 1970. In sum, the timing between the start of our paper record and building completion extends to only a single year.

The city archives date the building permit for it to October 1969 for 86 units, with permit value of $635k. The building completed only about one year later, around which time it got advertised in the newspapers, as in this excerpt from the Vancouver Sun from October 1970. In sum, the timing between the start of our paper record and building completion extends to only a single year.

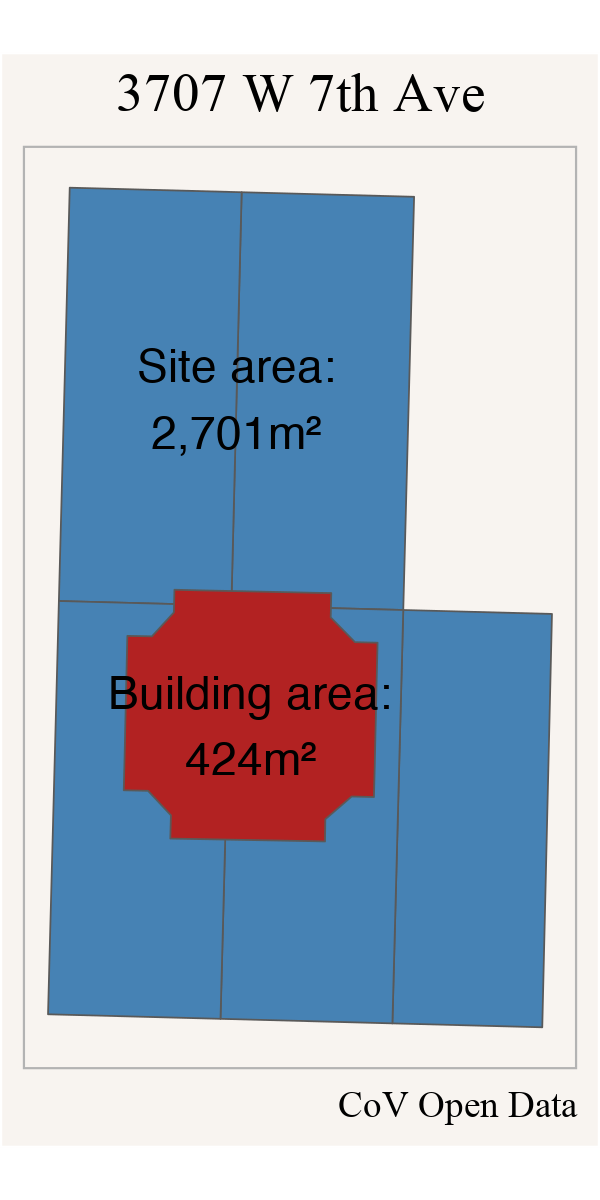

To understand how the zoning enabled (and forced) the form of this 12 storey building, we can take a look at the parcel and building footprint.

The building had a site coverage of 16%, which gave it a density bonus of 0.51 FSR. The site area bonus fetched the maximum allowed 0.25 FSR, and additionally there was an FSR bonus of up to 0.2 for the share of parking that is directly under the building footprint, for a total of between 1.76 and 1.96 FSR, depending on how parking is configured. The total gross FSR for the 12 storey building, estimated from LIDAR data, is approximately 1.88 which falls right into that outright allowed range.

By contrast, as the area got downzoned, our example building became impossible to rebuild. The reduction of height made the FSR bonusing challenging, and building nearly any kind of apartment building came to rely upon the discretion of the Planning Board. Apartments had to spread out, reducing our lot coverage bonus, and limiting the maximum achievable density on the site to 1.6 FSR.

Looking at lots nearby, low-rises later constructed within the downzoned RM-4 contained less floor space relative to lot size and significantly fewer apartments. And apartments in the area did not get cheaper. At the time we write this, a 635 sqft 1 BR apartment at 3707 w. 7th is currently on offer at a rent of $2,575/mo.

The lack of secured rental apartments in Vancouver is precisely what the MIRHPP policy was meant to address. So let’s take a look at how that’s going!

Under Construction at Alma and Broadway

Everyone heading from west along the Broadway Corridor is familiar with the short hitch in their path at Alma as they scoot over to 10th to continue their journey to UBC. In 2022, a construction crane was added as a new landmark at the hitch, marking the intersection of Alma & Broadway as the site of our MIRHPP project. As we write this we’re just beginning to see reinforced concrete peeking up above the excavation work.

Prior to demolition, the corner lot for our development held a small Commercially zoned strip mall, similar to the one nearby on the SE corner of 12th & Alma. Its most notable tenant was probably True Confections dessert restaurant, which moved down the street to Broadway & Collingwood in 2020. The lot, assembled together with a neighbouring house, had been purchased by developer Westbank in 2011 for about 9.4 million dollars.

Why did the site take so long to redevelop? We don’t know the whole story, but we suspect Westbank spent a fair amount of time reading the tea leaves of City Hall (as we discuss more below) and we also know that low-rise commercial often remains resilient to redevelopment in part because landlords are happy to continue raking in the rents while they decide what to do (the site’s rents were estimated at $110,000 a year in 2011, even with one storefront untenanted, while commercial tenants often pay property taxes). From here on out we’ll focus on when we know development plans began to advance, at which point we acquire a lengthy regulatory record based in rezoning, development permitting, and building permitting.

Rezoning

An initial rezoning application came in in December 2016 with open house in April 2017 to develop six-storey mixed-use structure with 94 rental apartments, built in a way so that another 6 storeys could be added at some later point in time. Adding floors to an existing building is such a great way to add housing that Germans invented a whole new word for it. But typically new floors are added decades or even centuries after a building was built, when the urban environment changes and the complex work to add floors to an existing building becomes economically viable. In this case the final 12 storey building was already economically viable, but politically it was dead in the water. Therefore the developer opted for the more costly two-phase approach, building a six-storey building immediately, but designing it in a way so that another 6 storeys could be added later if and when the political climate shifted.

That political shift came faster than anticipated! The project was put on hold after the open house in 2017. Taking advantage of the new MIRHPP policy (approved by City Council in November 2017 and taking applications beginning in January 2018), the developer returned on November 15th, 2019 applying for a rezoning of the existing C-2 strip mall and adjacent vacant RS-1 lot to build a 14 storey rental building with 20% of the units below market in perpetuity. The City scheduled another open house for February 13th, 2020. With only minor interruptions due to the pandemic, the process continued on, with changes to the proposal made in response to the open house by May 2020. An on-line public hearing for the rezoning was scheduled for October 27th, 2020, but took two extra days because of the long list of speakers, many vehemently opposed (by contrast, the owner of True Confections spoke in favour). The rezoning passed on October 29th, 2020, including 153 secured rental apartments (20% rented below market at rates well below those on offer at 3707 W. 7th). Notably the rezoning was approved under a different council than passed the MIRHPP policy, with an uncertain-seeming, but ultimately decisive 7-3 margin. Overall it took almost a year to get site-specific zoning in place closely tailored to the proposed building parameters, not counting the multiple years of planning and time to do the initial design work and negotiate with staff through the pre-app phase.

Development Permit

However, the rezoning does not allow the proposed building to go forward outright, the zoning is only “conditional”. It still requires a discretionary Development Permit, which comes with another round of more detailed renderings, public feedback and, if things go well, staff approval. The City received the Development Permit application on December 16 2020, with a public comment phase between February 2nd to February 26th 2021. The development permit board approved the (slightly modified) project on May 17th, 2021. The actual Development Permit was not issued until March 1st, 2022, a little over two years after the final rezoning application was submitted and following the excavation and shoring up of the site.

However, the rezoning does not allow the proposed building to go forward outright, the zoning is only “conditional”. It still requires a discretionary Development Permit, which comes with another round of more detailed renderings, public feedback and, if things go well, staff approval. The City received the Development Permit application on December 16 2020, with a public comment phase between February 2nd to February 26th 2021. The development permit board approved the (slightly modified) project on May 17th, 2021. The actual Development Permit was not issued until March 1st, 2022, a little over two years after the final rezoning application was submitted and following the excavation and shoring up of the site.

Building Permit

The Building Permit is what’s needed to ensure that the building conforms to all the building codes, making it safe to live in and conforming with all the other requirements the City places on new buildings.

In Spring 2021, compliance with the zoning wasn’t fully in place yet with the development permit still outstanding, but the developer submitted permit applications for salvage and abatement as well as for demolition on April 4th, 2021 to clear the site of the existing strip mall. The developer applied for the Stage 1 Building Permit for excavation and shoring up on May 14th, just before the Development Permit Board hearing. The salvage and abatement permit came through on July 7th, 2021, and the demolition permit and building permit followed on August 24th and September 29th, respectively, taking the City 138 days each to process. At that point, the construction crews could finally get to work.

Construction

We are not sure precisely when demolition or construction for this site started, but it took some time to excavate and shore up the site. The digging was well underway by Spring 2022.

While digging the developer would have applied for Stage 2 of the building permit to get permissions for foundation and building up to grade, which would have been granted sometime after the Development Permit was granted on March 1st 2022. As construction below ground progresses the developer would have applied for Stage 3 of the Building Permit for full construction. Unfortunately the City Open Data permit data does not track the different stages of the Building Permit, so we can’t reconstruct the exact timelines of these. But the crane was installed in June of 2022.

The next data point we have is a building “start” from CMHC for 164 rental apartment units in September 2022 in the census tract for the site, exactly matching the count of rental units from the DP application. At this point parts of the construction are still just now peeking up from below ground level. Westbank still projects a completion date of “2023” but this seems… ambitious. Regardless, it will still take some time before these units “complete” in CMHC data and begin to welcome new residents.

Overall, the lengthy timeline of the Broadway/Alma project speaks to how developers may try to reduce risk by buying land proactively well in advance of when they intend to develop it, waiting for the right timing to develop. Similarly, developers might start rezoning and permitting processes prematurely, abandoning or renegotiating as conditions change. Of course only well-capitalized developers have the resources to do this. This behaviour, incentivized by the Spot Discretionary Regime, is sometimes called land banking or permit banking. But the focus should probably turn from developers here, to where their attention has been rationally redirected by the Spot Discretionary Regime: the politics and policies of City Hall. In many respects, the practices of the Spot Discretionary Regime effectively prevent land from being developed until the diverse and changeable priorities of City Hall align with the generally more constant priorities of developers.

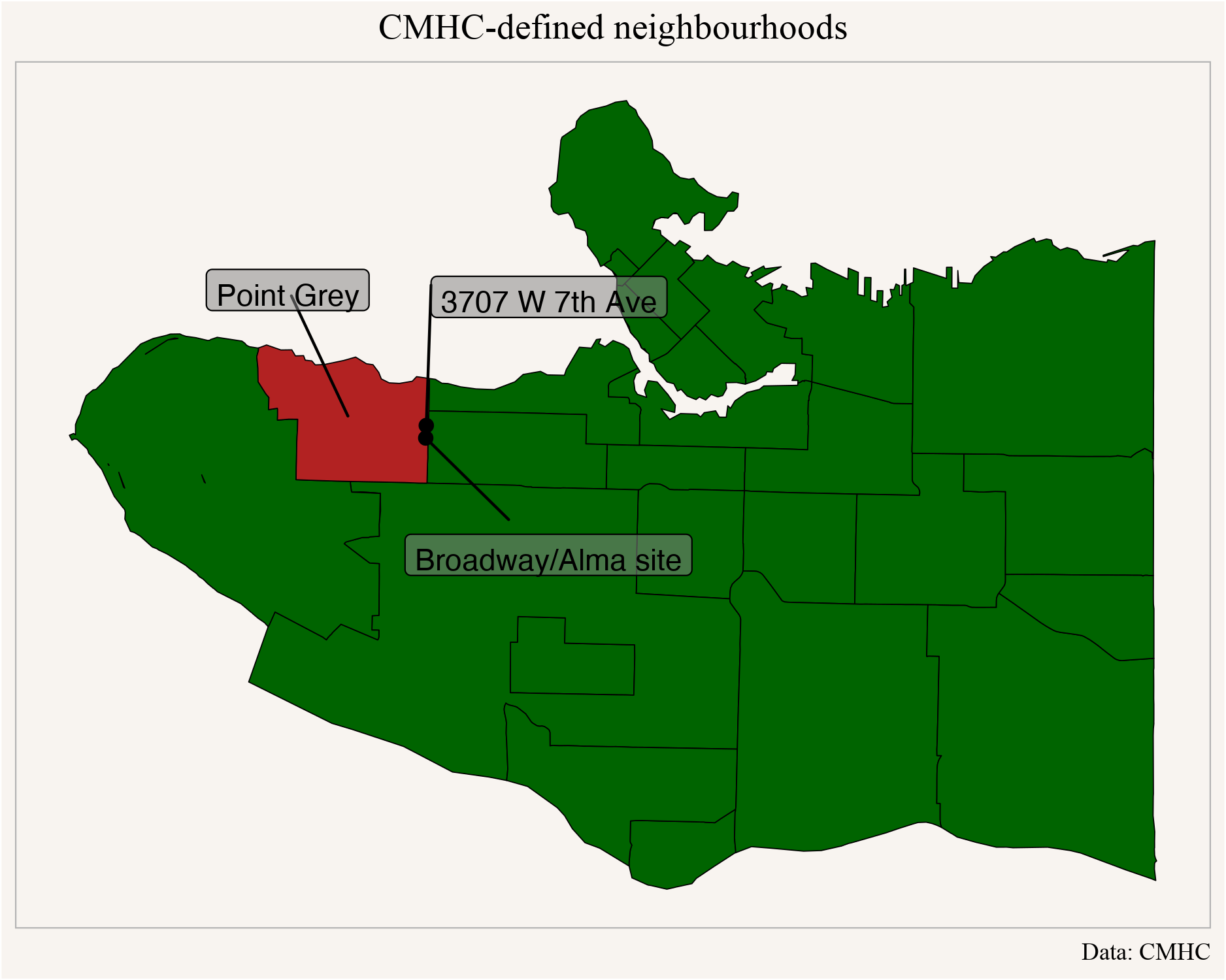

The Point Grey neighbourhood

Let’s take a look more broadly how this has played out in the Point Grey neighbourhood, where the Alma/Broadway project, as well as the apartment building from 1970 pictured above, are located. Here is how this neighbourhood is defined in CMHC data.

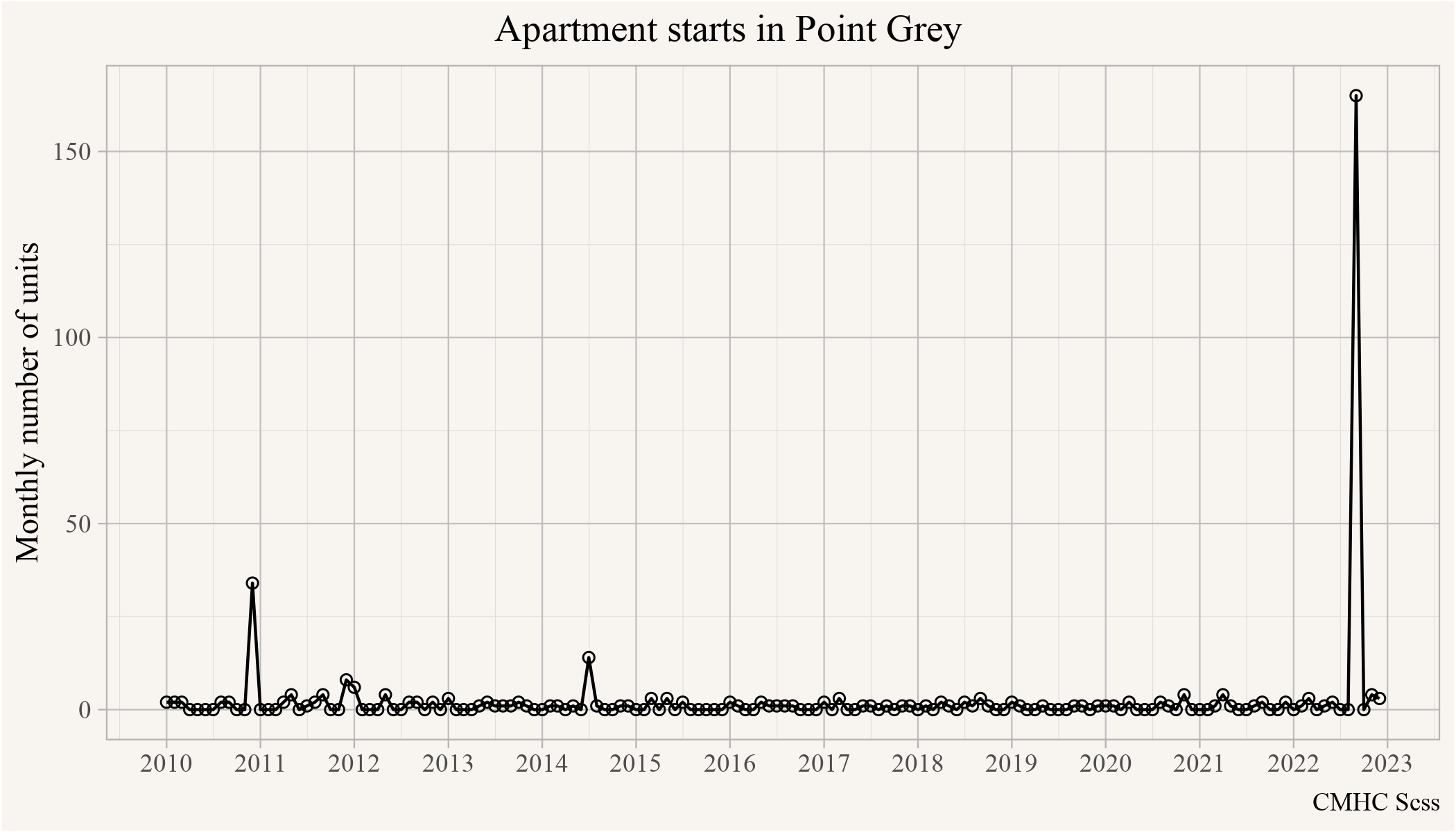

How many condo or rental apartments have been built in that area? CMHC data at the neighbourhood level goes back to 2010.

And as one might have expected, very few apartments have been built. A recent low-rise mixed-use commercial (C-2 zoning) with 36 apartments over top shows up as a 2010 start (completed in 2012 near Discovery & 10th). Some of the rest of the low level noise is due to secondary suites, which CMHC data counts as single rental apartment units. The apartment ban gradually installed through the transition from the Zoning for Growth to the Spot Discretionary Regime has been very effective in Point Grey. As a result, the Broadway/Alma project registering as a 2022 start really stands out.

As for that Broadway/Alma project, it’s worth remembering that in the near future it should be sitting practically on top of a new SkyTrain Station, and just to the East of the soon-to-be-booming Jericho Lands. Point Grey is about to change. But it remains to be seen how fast. The clock has already started.

Takeaway

From 1970 to 2022 we shifted between two different planning and development regimes. The Zoning for Growth Regime definitely had its problems, but if it allowed you to build something, you knew you could build it, and you could build it quick. The zoning change in 1961 enabled and encouraged towers, and as far as we can tell, the developer of 3707 W. 7th needed only their building permit issued in 1969 to construct their 12-storey tower by 1970. Shortly thereafter we shifted into our current Spot Discretionary Regime. Here the developer purchased the assembled lot in 2011, began wading through political currents of rezoning in December 2016, only to dive in fully after policies shifted with a rezoning application in November 2019, approved in October 2020, with development permit and building permit processes holding up excavation till Spring of 2022. It won’t be done till the end of 2023 at the absolute earliest, some 4-12 years after the process began, depending upon when one starts the clock.

In the Zoning for Growth Regime developers were able to be responsive to changes in prices and add housing fast, purchasing development sites with full understanding what could be built and only needing a building permit. This reflects what economists call “supply elasticity,” or the ability for markets to serve as a mechanism linking increases or decreases in construction activity to increases or decreases in demand as expressed through changes in prices or rents. So long as outright zoning contained ample capacity to accommodate growth, generally reflected in upzoning in Vancouver until 1972, housing supply generally responded to housing demand.

The Spot Discretionary Regime directly targeted the market mechanisms enabling additional housing to be added in response to demand. The added uncertainty introduced by new discretionary processes required developers to speculate on what could be built when buying lots, adding risk. This process selected for developers well connected with City Hall and acquiring a deep understanding of the inner workings of the planning department. It also selected for developers who were well-capitalized to be able to handle the additional risk. The substantial lengthening of permitting times made an effective market response to changing prices next to impossible. Given 4+ years of process, the market at the time a new housing project completes could be quite different from the market when the housing project began.

This is not to say that market mechanisms are all that we should pay attention to, but they’re certainly key to getting more market affordability and evidence strongly suggests the Spot Discretionary Regime works no better in getting non-market housing built. This is also not to say that market mechanisms have disappeared. Indeed, they still work during downturns, when (well-capitalized) developers can abandon or delay projects working their way through the approvals timeline as economic conditions become less favourable. In effect, the Spot Discretionary Regime has broken broken supply elasticity and replaced it with a ratchet. On upswings, planners limit how much housing developers can initiate and on downswings developers withdraw from projects that look like losers. The end result: supply hardly ever catches up to demand. And housing keeps getting more expensive.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2023-02-07 09:46:33 PST"## Local: master /Users/jens/Documents/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [8a5d962] 2023-02-07: link to nathan## R version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31)

## Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Ventura 13.2

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] VancouvR_0.1.7 mountainmathHelpers_0.1.4

## [3] sf_1.0-9 cancensus_0.5.5

## [5] cmhc_0.2.4 forcats_1.0.0

## [7] stringr_1.5.0 dplyr_1.1.0

## [9] purrr_1.0.1 readr_2.1.3

## [11] tidyr_1.3.0 tibble_3.1.8

## [13] ggplot2_3.4.0 tidyverse_1.3.2

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] httr_1.4.4 sass_0.4.5 jsonlite_1.8.4

## [4] modelr_0.1.10 bslib_0.4.2 assertthat_0.2.1

## [7] triebeard_0.3.0 urltools_1.7.3 googlesheets4_1.0.1

## [10] cellranger_1.1.0 yaml_2.3.7 pillar_1.8.1

## [13] backports_1.4.1 glue_1.6.2 digest_0.6.31

## [16] rvest_1.0.3 colorspace_2.1-0 htmltools_0.5.4

## [19] pkgconfig_2.0.3 broom_1.0.3 haven_2.5.1

## [22] bookdown_0.32 scales_1.2.1 tzdb_0.3.0

## [25] git2r_0.31.0 timechange_0.2.0 proxy_0.4-27

## [28] googledrive_2.0.0 generics_0.1.3 ellipsis_0.3.2

## [31] cachem_1.0.6 withr_2.5.0 cli_3.6.0

## [34] magrittr_2.0.3 crayon_1.5.2 readxl_1.4.1

## [37] evaluate_0.20 fs_1.6.0 fansi_1.0.4

## [40] xml2_1.3.3 class_7.3-21 blogdown_1.16

## [43] tools_4.2.2 hms_1.1.2 gargle_1.3.0

## [46] lifecycle_1.0.3 munsell_0.5.0 reprex_2.0.2

## [49] compiler_4.2.2 jquerylib_0.1.4 e1071_1.7-13

## [52] rlang_1.0.6 classInt_0.4-8 units_0.8-1

## [55] grid_4.2.2 rstudioapi_0.14 rmarkdown_2.20

## [58] gtable_0.3.1 DBI_1.1.3 R6_2.5.1

## [61] lubridate_1.9.1 knitr_1.42 fastmap_1.1.0

## [64] utf8_1.2.3 KernSmooth_2.23-20 stringi_1.7.12

## [67] Rcpp_1.0.10 vctrs_0.5.2 dbplyr_2.3.0

## [70] tidyselect_1.2.0 xfun_0.37Reuse

Citation

@misc{a-brief-history-of-vancouver-planning-development-regimes.2023,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {A {Brief} {History} of {Vancouver} {Planning} \&

{Development} {Regimes}},

date = {2023-02-06},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2023-02-06-a-brief-history-of-vancouver-planning-development-regimes/},

langid = {en}

}