(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

With last week’s CHSP release of data on the investment status of residential properties and the framing of the accompanying article there has been a lot of rather uninformed and misleading news coverage.

The misleading reporting, combined with sometimes plainly wrong statements by people quoted in the news coverage, on one hand highlights the poor understanding of housing in the public discourse. On the other hand it highlights the importance of providing careful framing with data releases. In general it is good practice to accompany a data release with a brief analysis to provide framing and context. Analysts close to the raw data will have a much better understanding of what the data is measuring and can properly frame the data. Unfortunately, StatCan fell short of doing so, and the overview analysis provided by StatCan itself contains a number of problems. Given the public attention this has gotten it’s probably worthwhile to take a look at what the data does and does not say, and to correct some of the misinterpretations that have been circulating.

The trouble with the definitions

For any data release it’s important to understand the definitions underlying the categorization in the data. Central to this release is how “investors” are defined.

In common language, “investors” are typically defined by motivation and expectation. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines “investor” as: “a person or organization that puts money into financial plans, property, etc. with the expectation of achieving a profit.” Statistics Canada does not have access to motivations or expectations through the CHSP program. This suggests they probably should have considered different language in this study, and at the very least have been prepared for a lot of misinterpretation in media coverage.

Rather than exploring motivation or expectation, we get a definition of which property owners are considered “investors” from Statistics Canada that simply groups by point-in-time category. So investors include:

- for-profit businesses

- governments

- individuals not found resident in the province

- individuals resident in the province owning more than one property

- individuals resident in the province owning a property with more than one residence

We want to pause for a moment here to ponder the choice to include governments as investors. Governments do indeed own a fair amount of property (see, for instance, the City of Vancouver’s vast holdings), but it’s odd to speak of governments as investors. To be sure, they rent out properties and receive incomes on them, but usually holdings have to do with planning objectives and other government purposes.

Stranger yet, we’re told governments are combined with for-profit businesses in reporting, and, “Given the predominance of businesses in this category, they will simply be referred to as “business” in what follows.” This is an odd choice, and surprisingly sloppy coming from StatCan. A StatCan article from November of 2022 initially reporting on business and government ownership, for instance, retained both in the title of the category to avoid misinterpretation in collapsing the two. The collapse of the distinction here seems like a red flag by comparison, especially within a context where “investors” are likely to be interpreted as uniquely profit oriented in media coverage.

What of other groups included? Statistics Canada is implicitly making some very strong assumptions here about who is profit motivated and who isn’t. Purchasing a home for a family member to use? Investor. Resident homeowner basing retirement plans on best time to cash out their equity? Non-investor. Vacation home owner? Investor (but only if their primary residence is also owned, they’re not an investor if their primary residence is rented). Even in these few examples, we can see how temporal considerations might also matter. In practice, property owners regularly shift their motivations and relationships to properties through time, problematizing their neat division into “investors” or “non-investors” assessed at any particular point in time. Similarly, organizations like non-profits, automatically exempt from the definition of investor here, often run some housing as market housing, redirecting profits to support subsidies for other housing.

Overall, we can cut Statistics Canada some slack here in laying out their categorical definitions insofar as they’re not the only ones making these assumptions. But these assumptions should be treated critically and carefully, ideally making them explicit by discussion of their pros and cons. Here StatCan can do a lot better, and usually does.

Statistics Canada moves on from defining categories of investors to defining investment properties. This adds a new layer of complication insofar as matching owner categories to property categories is tricky. After all, single owners can hold multiple properties (part of the definition used for “investors”). Moreover single properties can have multiple owners and contain multiple dwellings. Grouping properties by buildings doesn’t help us here, and in fact adds to the complexity insofar as single properties can have multiple buildings, and single buildings can contain multiple properties (legally structured through condominium or strata legislation). Here all the complexity of matching owners to properties to dwellings gets swept up into three new categories: investment properties, owner-occupied investment properties, and non-investment properties. To simplify:

- A non-investment property is a property with a single dwelling unit which is either

- the primary residence of at least one of the owners, or

- the sole property of each of the owners, all of which residing somewhere in the same province

- An owner-occupied investment property is a property with multiple dwelling units that is the primary residence of at least one of the owners.

- An investment property is everything else.

Part of the confusion in the media stems from the distinction between investment property and non-investment property remaining ambiguous about how the property is actually used, as we have already seen in the example of vacation properties above. Consider how a property with a single dwelling unit that is rented out could be classified as either one. Same for a property that is left empty.

The property use that the definition is less ambiguous about is if the property is in some way owner-occupied. In that case it is not solely an investment property, but it could be either a non-investment property or an owner-occupied investment property. Here adding a separate suite, often known as a “granny flat, automatically shifts a property into investment status, even if the owner’s granny moves in, or if nobody moves in and it’s still used as part of the living area of the main owner-occupied unit.

This wouldn’t matter a great deal if the stakes for being considered an investor didn’t seem so loaded with negative connotations. Maybe there is some real estate investment we want? In particular, many people have pointed out our housing shortage in Canada, where we’re especially short on rentals. The StatCan release notes that rental properties

contribute to the rental housing supply—and therefore meet the population’s need for rental housing – but that can also limit the number of properties available to buyers who intend to use it as a primary place of residence.

On the one hand this hints at a desire to elevate home ownership (by owner-occupiers), on the other hand it ignores the structure of single properties with multiple dwelling units, which cannot be made legally available for separate sale. And things get even more fuzzy when we get to purpose-built rental properties, which can produce misleading quirks in the data as we will discuss below.

Likely for this reason the press release has focused on houses defined as single-detached houses, semi-detached houses, row houses, and mobile homes, and condominium apartment property types when reporting statistics and comparing across jurisdictions. That does avoid some of the problems by excluding properties with multiple dwelling units. It filters out suited single family homes as well as large portions of purpose-built rental buildings, depending on how they are legally structured. But it’s still a statistic that can produce highly misleading results running counter to expectations of the casual reader, as we will explain further below, and CHSP fails to provide proper guidance.

In summary, we believe the definitions in this data release aren’t particularly useful in providing meaningful information about Canadian housing, and they aren’t sufficiently contextualized to provide a non-expert the means to adequately interpret the data.

What is a condominium apartment?

Much of the news about the release has focused on condominium apartments. Colloquially these are often referred to simply as “condos”, but there are some important differences between the colloquial understanding and the formal definition by StatCan.

Condominium refers to the legal form of ownership, also called strata in some parts of the country, which divides air parcels or land (“bare land strata”) so it can be sold and owned separately while some elements are held in common ownership. It makes owning individual apartment units possible, but also applies to many semi-detached houses (also know colloquially as “duplex” in some parts of the country), townhouses, bare land, as well most recently to imaginary units created solely for property tax purposes (“air parcels”).

Apartment is a structural type of dwelling, which for StatCan refers generally to structures with three or more units.

Condominium apartment consequently denotes the intersection of those two concepts, or as explained in the data release

A condominium apartment refers to a set of living quarters that is owned individually, while land and common elements are held in joint ownership with others.

But there is important nuance to this, notably strata titled purpose-built rental apartments. These function and operate just like a purpose-built rental apartment structured legally as single ownership freehold, except it is legally structured as condominium, making each unit it’s separate legal entity but all units, while “owned individually” are held by the same owner. In the BC data underlying the CHSP building stock data, purpose-built rental apartment structured legally as condominium are identified by actual use codes 058 and 059, as opposed to actual use code 030 for condominium apartments which are generally sold and owned individually. The CHSP data does not distinguish between these two, and more importantly, fails to provide this context. This fundamentally challenges the framing provided in the overview analysis. The disparate treatment of purpose-built rental buildings depending on how they are legally structured causes problems when interpreting the data, in particular when the share of condominium titled purpose-built rental units among all condominium apartments varies across geographies.

Purpose-built rental buildings

One type of investment property that most people believe we should have more of is purpose-built rental buildings. These can be classified in a variety of ways, if the owner lives in one of the units it will be an owner-occupied investment property, if the owner does not live there it will be an investment property, and if the purpose-built rental building is legally structured as condominium, then the building will be classified as many investment properties, one for each dwelling unit (or strata lot). And this last point also shows how even simple statistics like the total share of properties that are investment properties in a given municipality can become very misleading.

To put it simply, big apartment buildings can show up as a lot of properties when structured into condominium, or a single property when structured like most purpose-built rental. But sometimes purpose-built rental is ALSO structured like condominium.

For example, focusing in on condominium apartments in the city of Vancouver as reported in the CHSP data 41.5% of the properties are classified as investment properties. But about 5% of these, roughly half of the 10.1% of the condominium apartment units owned by businesses, are in purpose-built rental apartments that happen to be legally structured as condominium. To give a specific example, the Peter Wall Yaletown at 1310 Richgards is a rental building that is legally structured as condominium; each individual unit is legally separated into it’s own strata lot.

The public generally is not attuned to how a purpose-built rental building is legally structured, renters won’t be able to tell the difference unless they look it up in land title data.

In Vancouver this does not make that much of a difference, the share of non-purpose-built rental condominium apartments that are investment properties is 38.4%, not much different from the overall. Where it does make a difference is when news articles and commentators talk up the business-owned condominium units and fail to provide this context. After all, the condominium titled purpose-built rental apartments make up a significant share of the business-owned investment condos.

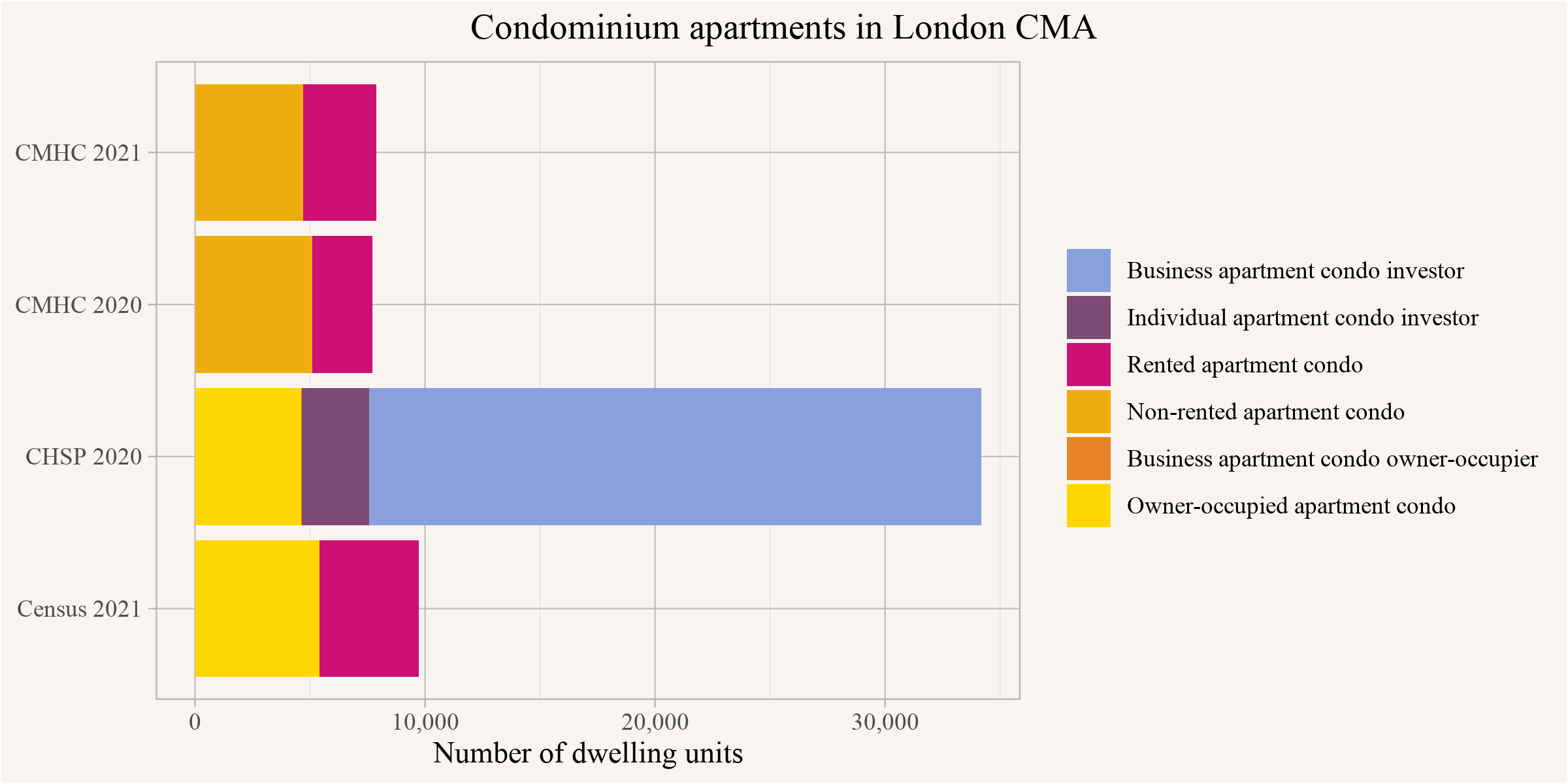

This problem of inadequate framing from StatCan get’s even more concerning when condominium titled purpose-built rental buildings make up a much larger share of overall condominium units. In London, Ontario, news reports took StatCan data at face value and headlined [“More than 86 per cent of London’s apartment condos are owned by investors: StatsCan”]((https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/london-ontario-investment-property-1.6739784) and falsely interpreted this as “a sign first-time buyers are being squeezed out of the market by investors, who are cashing in on the city’s severe undersupply of purpose-built rental apartments” instead of simply this being part of the purpose-built rental apartment supply. We can observe the echo of this by contextualizing the data with other data sources, in particular the Census and the CMHC condominium apartment secondary rental market survey.

It is important to recognize that these other data sources differ in how data was categorized and what concepts are measured. The CMHC condominium apartment universe will exclude apartments that are classified as part of the primary rental market, so it will excluded condominium titled purpose-built rental apartments. On the other hand, the CMHC survey may have gaps that can skew the data.

Census data only reports on condominium units that are someone’s usual place of residence, so it will miss units that are unoccupied or occupied by temporarily present persons like students who return to live with their parents over summer. The Census determines the condominium status of a dwelling unit by asking the respondent, which will yield a different response than when accessing the legal status from administrative data. For example residents of bare land strata will often incorrectly report not being part of a condominium development. More important for our purpose, renters may be much less aware whether their rental home is condominium or not. In particular, renters in a purpose-built rental apartment will generally not know about the underlying legal structure of their building and self-report as not living in a condominium unit, whereas renters renting from individual owners within a condominium apartment generally report as living in condominium.

Despite of, and sometimes because of these differences, important information can be obtained by comparing these data sources.

We see that the overall CMHC condominium apartment universe is lower than the estimate of occupied (by usual residents) condominium apartment units from the Census, and the same is true for the number of rented condominium apartment units. Moreover, CHSP seems to under-estimate the owner-occupied stock, as should be expected given the biased error distribution inherent in the classification method. What stands out most, however, is the large difference in number of condominium apartment units in the CHSP data compared to the other two data sources, and that this can be to a very large extent attributed to business-owned condominium apartment units.

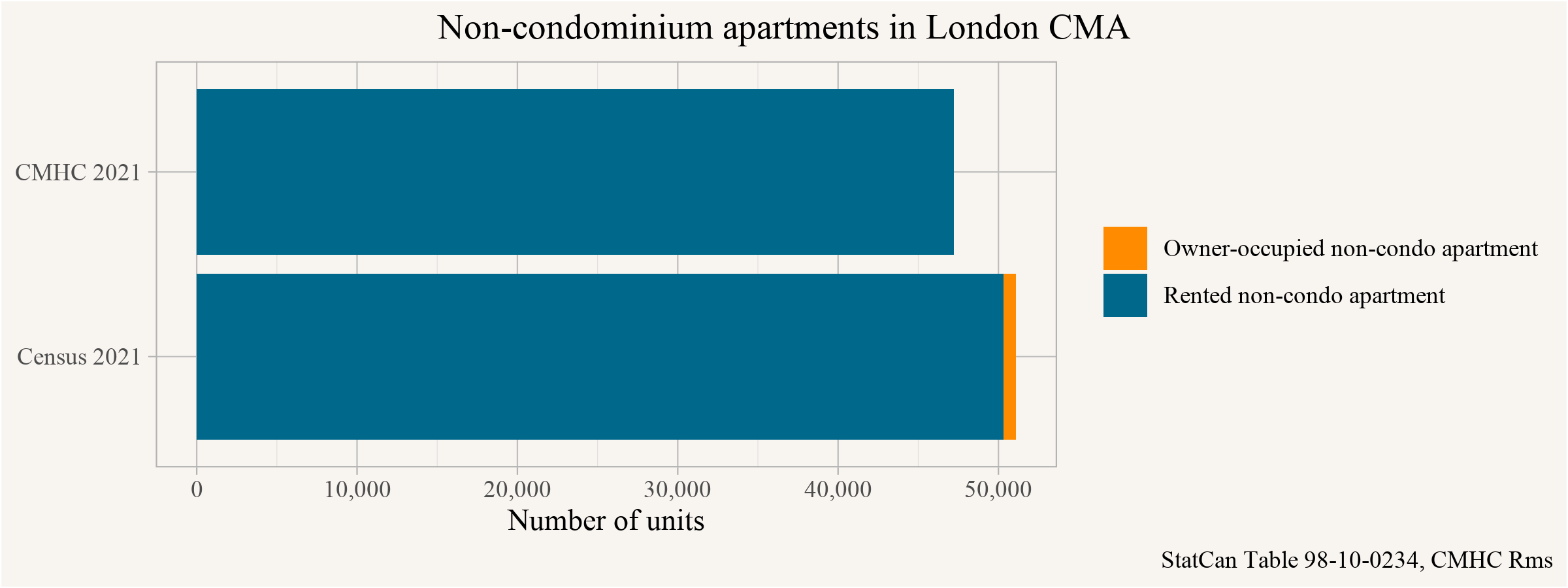

To confirm this we can compare the CMHC primary apartment rental market universe, which contains condominium titled purpose-built rental buildings, to the non-condominium apartment units identified in the census. One note here is that CMHC only counts structures with at least six rental units, while the census will identify buildings like single family homes with two secondary suites as apartments, so there are some differences to be mindful of.

The match between those two is quite strong, lending strong evidence to the hypothesis that a very large portion of the apartment condominium units are condominium titled purpose-built rental units.

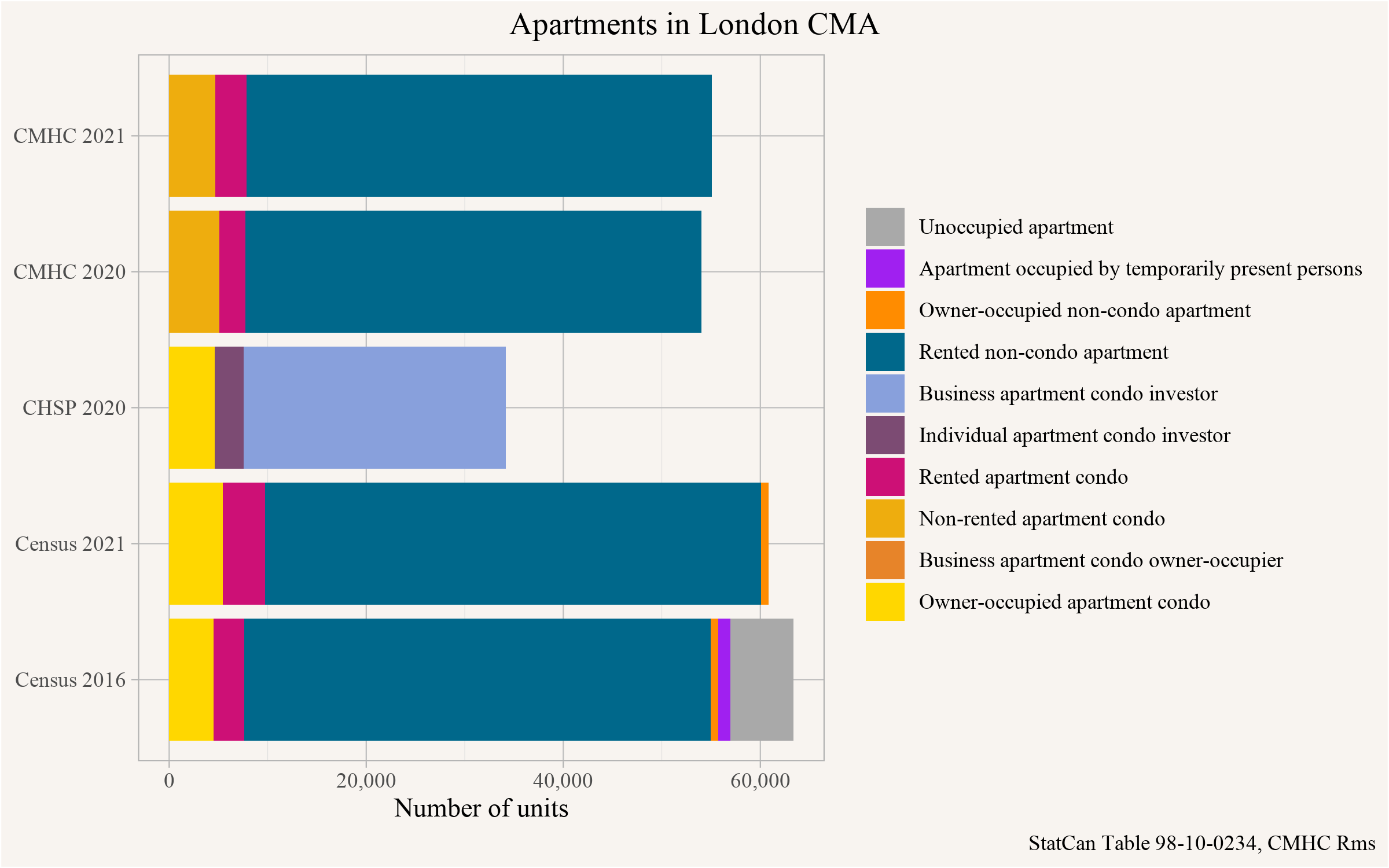

To wrap this up we can put those together to understand the total apartment building stock, remembering that CMHC rental apartments only count units with six or more units.

We added in data from the 2016 census for which we have information on how many apartment units were occupied by temporarily present persons or were unoccupied, to have a more complete picture of the entire apartment dwelling stock as classified by the census. Unfortunately we don’t have this data for the 2021 census at this point. The apartment stock has likely grown between the 2016 and 2021 census. This is meant for reference to contextualize the 2021 census data on the apartment units which are occupied by usual residents. Also note that “unoccupied” apartments should not be confused with long term empty homes.

This shows that the overall number of units estimated by CMHC and the census still line up reasonably well. the CHSP data only counts condominium apartments, and comparing to the other data sources we conclude that the overwhelming majority of business investor condominium apartments are in purpose-built rental buildings that neither CMHC, nor renters self-reporting in the census consider to be “condos.” Here the legal structure departs from the common-sense and practical definition. These units are not available for sale to residents, nor are they governed in a similar fashion to other condominium units. But the CHSP release ignores this distinction, correspondingly boosting estimates of investor-owned properties relative to if they were treated as singular purpose-built rental properties. The gap between the totals from the CHSP data and the other data sources is attributable to London also having purpose-built rental buildings that are not legally structured as condominium. Moreover, this highlights the distinction between properties and dwelling units, which makes it impossible to complete the comparison by adding in non-condominium apartment units in the CHSP data since the CHSP reports only on properties and does not allow to enumerate dwelling units.

New condo stock

To touch on a few other points, new condominium apartments will show up with higher rates of investor ownership in the CHSP data for several reasons. A simple one is unsold new inventory, which CHSP data will identify as investor units held by a business. Apart from that we generally see higher rates of transactions, and associated transactional vacancies, for new condominium apartment stock due to condominium apartment financing. Moreover, CHSP methods will likely under-estimate owner-occupiers for recent movers. This is basic context for anyone familiar with housing, making it surprising to see commentators trying to interpret this as a trend of increasing investor activity.

Emphasizing “foreignness”

Another problematic aspect of the choice of definitions in the CHSP release is the prioritization of “foreignness” in the classification of investment properties. The issue arises when an investment property has multiple owners on title, with some living in different jurisdictions. When classifying such a property as business and government owned, non-resident owned, out of province owned or in-province owned, priority is given if at least one of the owners falls into these categories in this order. This further emphasizes the “foreignness” bias inherent in CHSP’s owner matching methods. This is in contrast to how non-residency was treated in previous releases, where it was based on majority ownership or reported as mixed or pure residency status of owners.

Takeaway

In the past CHSP has added valuable data to enhance the understanding of housing in Canada. Unfortunately this release didn’t. The definitions used in the CHSP data release aren’t particularly useful to gain meaningful insights into Canadian housing, and the CHSP release fails to properly contextualize the data. Given owners’ shifting motivations and relationships to properties, we maintain that the most important question is how properties are used rather than how they are owned. That’s not to say that the complexities and motivations of ownership aren’t also interesting. But they’re not well captured here.

The choices by CHSP on how to slice the data are questionable on multiple grounds. We’ve demonstrated special problems with regard to how strata titled purpose-built rental apartments show up. The complete lack of disclosure of this when discussing condominium apartment investors in the CHSP overview analysis is highly misleading and in some cases directly responsible for the outright wrong news coverage on this.

Other context missing from the release is the historical data on multiple property ownership in Canada, readily available from other statistical datasets at StatCan, that would greatly assist in interpreting the data.

To move the discussion forward CHSP should focus on providing strong framing with data releases to avoid the media and public misinterpreting the data. Likewise, media, commentators, and the broader public need to pay more attention to definitions.

This does not mean that ownership of housing is not important; it is. But the motivations, expectations, and practices of property owners can prove elusive, and regularly shift over the course of the same underlying legal relationship. This is a challenge for trying to match data up to definitions of investment, let alone increasingly popular conceptualizations of terms like commodification and financialization as applied to housing, which rely upon strong assumptions about motivations, expectations, and practices. We’re very open to empirical contributions here, but ideally these contributions should directly address ambiguities and embrace underlying complexities, rather than sweeping them under the rug.

Lastly the meaning of ownership relative to renting is also complex and contingent. Aside from turning renters into owners, shifts in rental tenancy legislation can reset terms, providing access to the security many renters seek in ownership. In our mind a practical takeaway from the fact that many Canadians rent is that we should strengthen tenant rights, especially in the secondary market where most of the evictions happen.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2023-02-20 20:14:16 PST"## Local: master /Users/jens/Documents/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [df7e737] 2023-02-21: chsp investor post## R version 4.2.2 (2022-10-31)

## Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Ventura 13.2.1

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8/C/en_US.UTF-8/en_US.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] statcanXtabs_0.1.2 cancensus_0.5.5 cansim_0.3.14 cmhc_0.2.4

## [5] forcats_1.0.0 stringr_1.5.0 dplyr_1.1.0 purrr_1.0.1

## [9] readr_2.1.3 tidyr_1.3.0 tibble_3.1.8 ggplot2_3.4.0

## [13] tidyverse_1.3.2

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] lubridate_1.9.1 assertthat_0.2.1

## [3] digest_0.6.31 utf8_1.2.3

## [5] R6_2.5.1 cellranger_1.1.0

## [7] backports_1.4.1 reprex_2.0.2

## [9] evaluate_0.20 httr_1.4.4

## [11] blogdown_1.16 pillar_1.8.1

## [13] rlang_1.0.6 googlesheets4_1.0.1

## [15] readxl_1.4.1 rstudioapi_0.14

## [17] jquerylib_0.1.4 rmarkdown_2.20

## [19] googledrive_2.0.0 munsell_0.5.0

## [21] broom_1.0.3 compiler_4.2.2

## [23] modelr_0.1.10 xfun_0.37

## [25] pkgconfig_2.0.3 htmltools_0.5.4

## [27] tidyselect_1.2.0 bookdown_0.32

## [29] fansi_1.0.4 crayon_1.5.2

## [31] tzdb_0.3.0 dbplyr_2.3.0

## [33] withr_2.5.0 grid_4.2.2

## [35] jsonlite_1.8.4 gtable_0.3.1

## [37] lifecycle_1.0.3 DBI_1.1.3

## [39] git2r_0.31.0 magrittr_2.0.3

## [41] scales_1.2.1 cli_3.6.0

## [43] stringi_1.7.12 cachem_1.0.6

## [45] fs_1.6.0 xml2_1.3.3

## [47] bslib_0.4.2 ellipsis_0.3.2

## [49] generics_0.1.3 vctrs_0.5.2

## [51] tools_4.2.2 mountainmathHelpers_0.1.4

## [53] glue_1.6.2 hms_1.1.2

## [55] fastmap_1.1.0 yaml_2.3.7

## [57] timechange_0.2.0 colorspace_2.1-0

## [59] gargle_1.3.0 rvest_1.0.3

## [61] knitr_1.42 haven_2.5.1

## [63] sass_0.4.5Reuse

Citation

@misc{investing-in-definitions-and-framing.2023,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {Investing in Definitions and Framing},

date = {2023-02-20},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2023-02-20-investing-in-definitions-and-framing/},

langid = {en}

}