| Type | Units |

|---|---|

| Source: City of Vancouver | |

| Capacity in Existing Multifamily Zoning Districts | 25,700 |

| Capacity in Recently Approved CD-1 Districts (approved since 2009) | 15,137 |

| Capacity in ODPs, Community Plan Areas, and Policy Statement Areas | 35,420 |

| Total | 76,257 |

(Joint with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted at HomeFreeSociology)

Is there room for new housing? There are lots of ways to try and get at this question, driven by a variety of different value calculations (e.g. if you need housing you might look around and see room for more of it everywhere, but if you’re well-housed and like your neighbourhood just the way it is, then you might think there’s no room at all). But this can also be transformed into a technical question, where we can pin a definition down to potential methods for making more room. Here’s where we start to talk about planning concepts, including zoned capacity. Is there room for new housing in municipal planning practices and regulations?

BC has recently joined a host of other jurisdictions in passing a requirement that municipalities plan for housing needs, ideally making a lot more room for housing. In BC’s case this means planning for 20 years worth of growth required to meet housing needs. The calculation of housing need is, itself, a complicated endeavour, and we’re not convinced anyone is doing it quite right yet. But here we want to talk a bit about the planning side. If you have a number representing housing need to work toward, what does it mean to plan for that number?

As initially passed by the province, Housing Statutes Bill 44, Part 11 added Section 473.1 to the Local Government Act to require that “the statements and map designations included in an official community plan of the council of a municipality must provide for at least the 20-year total number of housing units required to meet anticipated housing needs, which total number is included in the most recent housing needs report.” Part 13 similarly added Section 481.7 to require municipal zoning by-laws to “permit the use and density of use necessary to accommodate at least the 20-year total number of housing units required to meet the anticipated housing needs, which total number is included in the most recent housing needs report received.” The bill further explained, in adding section 481.8, that “a zoning by-law must not establish conditional density rules for the purpose of achieving the minimum number of housing units required to be permitted.” Part 33 adds sections 565.08 and 565.09 to the City of Vancouver’s Charter with identical language. Later bills, including Bill 16 and Bill 18 from 2024, have further amended the Housing Statutes related to these acts (including requiring Vancouver to develop an OCP), but do not appear to have fundamentally altered their meaning. But what is their meaning? Aspects remain unclear. Moreover, as of this post, these parts of the bill have not yet been incorporated into the consolidated Local Government Act or Vancouver Charter (both purportedly current to April 24, 2024). This may be because they are not yet in force. According to the provincial timeline laid out by BC, June/July of 2024 will bring “guidance provided to municipalities to update Official Community Plans and zoning bylaws.” By Jan 1, 2025, “local governments must have completed their interim Housing Needs Report.” And due by by Dec 31, 2025: “municipalities update of their Official Community Plans and zoning bylaws (based on the interim Housing Needs Report).”

Both Planned Capacity and Zoned Capacity provide ways of defining the municipal planning side. Though still distinct, these terms have become increasingly connected insofar as rezonings that fit with Official Community Plans no longer go through City Council hearings. But “zoned capacity” is the way that the City of Vancouver has understood the task set for them by the province, building upon a contentious history of the term in local politics and their historical lack of an OCP. Effectively, this should translate into how much room for new housing has been opened up within current zoning. If there isn’t twenty years worth of anticipated housing need in there, then zoning needs to be modified so that more room for housing is opened up. But the devil is in the details, and when it comes to zoning, there are a LOT of details. Let’s take a closer look. In so doing, we’ll explore the concept a bit more in-depth, consider how conditions matter, add an estimate of the City of Vancouver’s zoned capacity that we did as part of the Metro Vancouver Zoning Project, and review the recent history of how the term zoned capacity has been used in Vancouver housing discussions.

Why do we care about zoned capacity?

Zoning has a complicated history, but it was initially marketed as a tool to direct and “rationally” manage growth - especially for the benefit of an emerging white middle class - rather than constrain or sharply limit growth. Correspondingly, the idea was that there should always be ample “zoned capacity” within existing zoning to enable growth. Zoning would direct developers where to go to build housing, but leave plenty of room overall for supply to meet demand.1

At some point a growing city will run out of zoned capacity as it gets used up, at which point the city needs to rezone to make more land, or height, or bulk, available for housing. Indeed, the planner Harland Bartholomew, hired by the City of Vancouver in the late 1920s to draft its first consolidated zoning plan, predicted his plan would only hold until around 1960. In effect, he thought he’d planned for about 30 years worth of housing need. Then the city would have to rezone to allow for more density. This is effectively what Vancouver started doing in many places after modernizing its zoning code in 1956 – right before the City turned around and downzoned many neighbourhoods in the mid-1970s. (von Bergmann and Lauster 2021, 2023a)

This all-too-brief history raises four characteristics of zoned capacity as a concept that are worth touching upon, and also speak to why we care about it.

- Zoned Capacity has important and long-known regulatory effects

- There are time lags that change these effects and challenge their observation

- Regulatory effects operate simultaneously at multiple scales

- Underlying regulations are complex and the capacity they create is tricky to define in practice

Harland Bartholomew was able to predict the need for updating and changing zoning over time based upon growth projections. In effect, he predicted that pressure from growth would rise over time as it bumped up against the constraints of his plan. With enough growth, it would become important to reconfigure the plan. In this, we can envision his plan as working something like a steam engine tank. We’ve long known it’s important how big that tank might be.

Just like it takes a little while for steam to build up in an engine, there are time lags to the effects of zoning constraints. If there’s enough room for growth in initial planning, then effects will be localized and overall pressure will be hard to detect. But as zoned capacity overall gets used up, the pressure rises everywhere contained by the code. Attributing this pressure back to the underlying regulation (specifying the size of our steam tank) can be challenged by the passage of time between observing the effects of pressure and onset of the zoning code. Putting this back in economics terms: the ability of supply to meet rising demand (a.k.a. supply elasticity) becomes increasingly constrained by zoning capacity in ways we shouldn’t expect to be stable over time, even though (and especially if) the underlying zoning code and map hasn’t changed at all. That boils over into rapidly rising prices.

To further complicate matters, the pressure produced by zoning codes isn’t just limited to the neighbourhoods directly affected by them, or even the municipalities contained by the zoning bylaw overall. Instead, pressure is felt regionally, across municipalities, over a relatively integrated metropolitan housing market. It can even touch neighbouring metropolitan areas. This pressure is a systemic effect, layered over top of variation in code specifics at the local level.

Zoning codes and their interactions with planning are notoriously complicated, tending to grow more so over time. Indeed, Bartholomew’s development plan for the City of Vancouver WAS his zoning code. Since then, development plans have been layered over top of zoning codes, with the idea zoning might be progressively changed to enable plans (with the right contributions in place from developers). Meanwhile, zoning codes have become both increasingly technical and restrictive at the same time they’ve become riddled with conditional permissions. This makes it really difficult to define zoned capacity at any single point in time, let alone study how it changes over time.

So we’ve long known zoned capacity is really important. The province is putting this knowledge into action by requiring municipalities to do the work Bartholomew suggested they’d need to do about a century ago. But it’s also become really difficult to observe and measure zoned capacity, setting aside carefully linking its effects to market forces of supply and demand.

We can’t address all of these issues here, but we want to think a bit more about the complexity of measuring zoned capacity (point four above). What exactly should be considered “zoned capacity”? How can it be quantified, and how much is “enough” to allow for a given estimate of housing need, or (even better) for organic growth in response to demand? These are important questions that the province is trying to hammer out with municipalities right now. We will try to give some preliminary answers of our own through the following sections.

What is zoned capacity? – A closer look.

At a simple level, zoning spells out what can be built where. For residential uses, our main concern, zoning spells out where residential uses are allowed and how much housing can be built down to the lot level. Aggregated across lots, zoned capacity is the difference of how much housing is allowed to be built in the city by the zoning bylaw compared to the housing that currently exists. “How much housing” already raises an interesting measurement question: are we interested in residential floor space? Number of bedrooms? Or number of dwellings? Different aspects of zoning code have something to say to each metric.

As we turn to exploring the metric for specific municipalities, starting with Vancouver, we add further complexity. As noted above, neighbourhood plans in Vancouver frequently differ from zoning. Moreover, the zoning bylaw distinguishes between outright zoning, developments that the zoning bylaw allows to proceed by building permit, and conditional zoning developments that the zoning bylaw may or may not allow (typically through development permit) but don’t require a rezoning. “Conditional” zoning in Vancouver is often highly discretionary. A prominent example in Vancouver is C-2 zoning, which makes up much of the commercial strips along Vancouver’s arterials. It allows a list of specified commercial uses (e.g. bowling alleys and retail stores) outright, but dwelling uses are only conditionally allowed, after the Director of Planning or the Development Permit Board first reviews:

- the intent of the zoning Schedule and all applicable policies and guidelines adopted by Council; and

- the submission of any advisory group, property owner or tenant.

While the maximum amount of housing the Director of Planning may allow is clearly spelled out in the schedule, the actual amount of housing that can reasonably be expected on a given parcel is far less clear. It might change over time as council changes guidelines, and it also depends on neighbourhood feedback. Established developers with a good relation to planners and tight grasp on neighbourhood dynamics may have a pretty good idea of what they can expect to be able to build. Outside developers with little experience in Vancouver may misjudge a specific site’s development potential.

For estimating zoned capacity this creates the challenge that it’s uncertain what level of discretionary density can be achieved on a given site, and Vancouver rarely allows the maximum discretionary density to actually be constructed. (von Bergmann and Lauster 2024) It also creates problems for cross-jurisdictional comparisons with jurisdictions where conditional zoning or density bonus schemes are encoded in bylaws and are predictable.

Estimating Zoned capacity in Vancouver

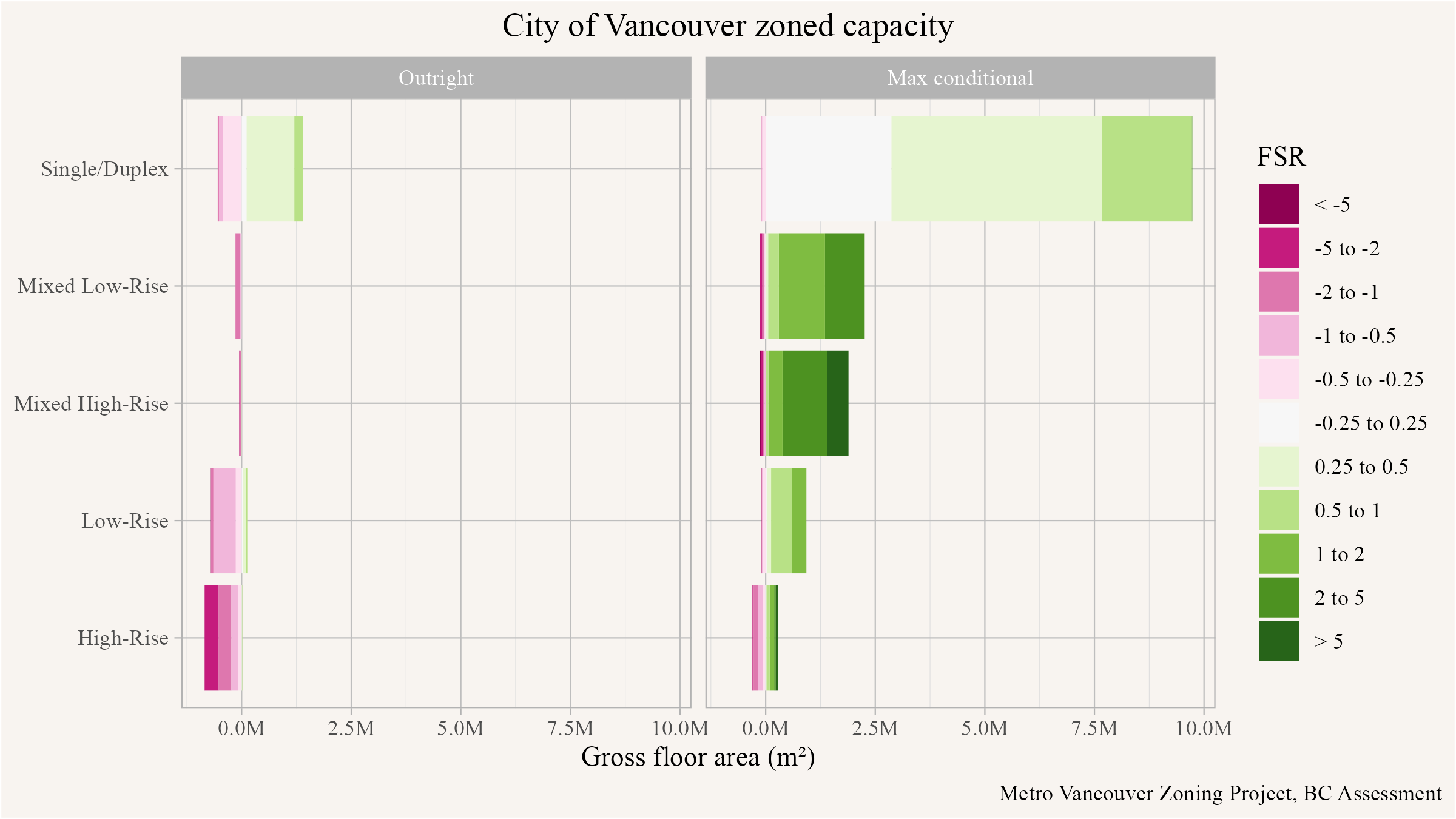

To make this uncertainty concrete, we can take a look at zoned capacity estimates in Vancouver that we did in conjunction with the Metro Vancouver Zoning Project, summarized in Figure 1. Here we focused on residential floor space. Our estimates are based on 2020 zoning data, so they do not reflect the recent changes to allow for multiplexes. They also require access to BC Assessment roll data to get a detailed understanding of current use, and this data is unfortunately not openly available.2 We express zoned capacity in terms of additional floor space allowed under current zoning and distinguished between outright and maximum conditional zoning to show the range of what might be allowed. Of note, the highly discretionary nature makes it difficult to distinguish which properties it may apply to, so we took the broadest possible approach and assumed that conditional zoning could be applied to all properties within each respective zone. Most of the additional zoned capacity in 2020 existed in RS and RT zones. It could be realized by tearing down smaller houses and replacing them with larger ones, probably adding more bedrooms, but generally very little in the way of more dwellings.

Were no new dwellings possible? If we consider theoretical maximum conditional zoning this adds considerable zoned capacity to low density zoning by allowing laneway houses and potential secondary suites, as well as highly discretionary density bonusing schemes that often rely on vague notions of “character” and aren’t available on all sites. The R1-1 multiplex zoning that came into effect after our estimates were done adds further conditional zoned capacity in terms of both dwellings (4-plex to 8-plex) and floor space.

On the larger-scale multi-family side we note that there is virtually no outright zoned capacity, and in fact a considerable amount of negative zoned capacity. Negative zoned capacity reflects the existence of non-conforming buildings that have a higher overall density than what current outright or conditional zoning allows. Some of these buildings pre-date the 1970s downzonings, others pre-date zoning altogether.

Setting these aside, there is some outright zoned capacity that our modelling could not account for. BC Assessment does not consistently keep data on floor area of rental buildings, and we have dropped rental buildings without information on existing floor area from the analysis. In most cases there was little zoned capacity available for these under existing zoning, but in some cases there were smaller footprint 3 storey rental buildings that could, conditionally, be torn down and replaced by slightly larger rental buildings without having to change zoning.

Most of the multi-family conditional zoned capacity exists in C-2 zones that conditionally allow for residential uses. To activate this requires redevelopment of the existing (mostly commercial) uses, and the conditional zoned capacity reflects the maximum allowable without changing the zoning, even if in practice this is rarely achieved. Some of the zoned capacity also exists within existing mixed use developments that have a residential component but do not achieve the full maximal conditional density.

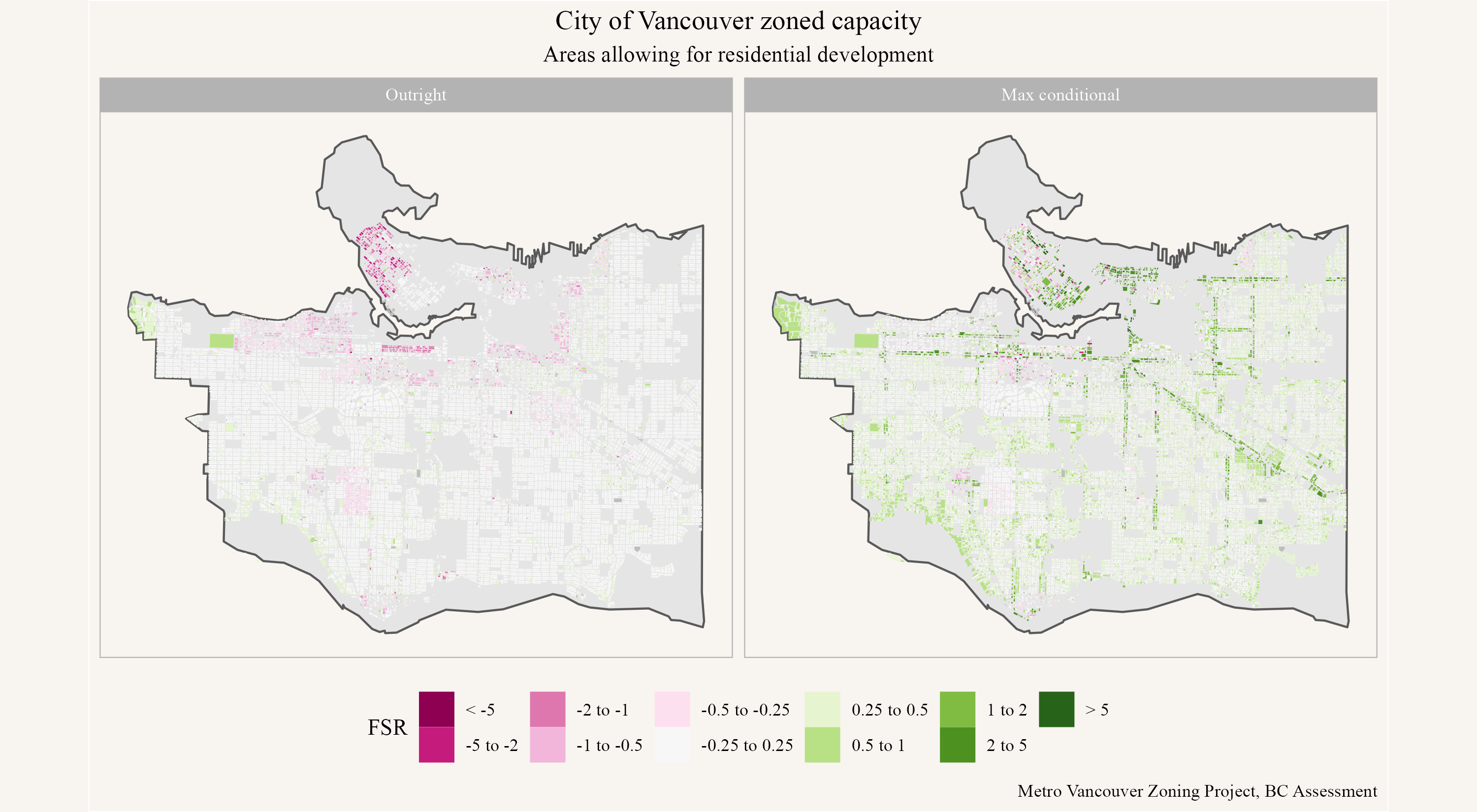

In Figure 2 we provide further context by mapping zoned capacity of each parcel zoned for outright or conditional residential use in the City of Vancouver. The map illustrates how most capacity sits along arterials within Commercial zones.

This view into the City of Vancouver zoned capacity opens up several questions on how zoned capacity might be useful. Zoned capacity generally requires teardown and redevelopment to unlock, although Aufstockung, the addition of storeys onto an existing building roughly translatable as “upstacking”, is in theory an alternative option. In practice economics and building engineering severely constrain the application of this strategy.

Zoned capacity and development outcomes

If we make room for more housing, will it get built? This is really important for linking zoned capacity to meeting housing need. And once again, the details matter here. If new zoned capacity adds more floor space without allowing for more dwellings (as has often been the case with single-family zones), then you probably won’t house many more people, perhaps just richer people. Other aspects of zoning codes (e.g. maximum heights, minimum setbacks, lot coverage rules, bedroom mix rules, minimum dwelling size, etc.) can also limit how much new housing gets added. Similarly, other policies (e.g. view corridors, non-market overlays, etc.) can alter the way zoning codes work to limit, or sometimes increase housing densities.

Development outcomes also respond to a variety of forces beyond municipal codes, of course. To (overly) simplify what’s likely to get built, it’s helpful to think in terms of developers making sequential assessments as per:

- What lots are for sale? (available capacity)

- What can be built on those lots? (zoned capacity)

- Is it worth it to build there? (viable capacity)

Even if zoned capacity gets added to a lot, it won’t matter for development outcomes unless the lot’s current owner either a) puts it up for sale, or b) partners up with a developer or takes on the role themselves. In practice, most developments involve a sale. (von Bergmann and Dahmen 2017) And there are many reasons why a property owner may not want to sell a property, even if the property is worth more as a redevelopment site than in its current use. It may be a single family home that the current owner lives in and does not want to move out of. It may be an investment or commercial property that generates a satisfactory steady income stream and the transaction friction is too high to trigger a sale. Owner decisions on the sale of properties are highly idiosyncratic.

Even if zoned capacity gets added to a lot, it won’t matter for development outcomes if the anticipated profit from redevelopment doesn’t make it worthwhile for a developer to take on. To calculate whether it’s worthwhile, developers typically write up a “pro forma” that pulls together their perceptions of residential demand (achievable sales prices and rents) with the likely costs involved in financing the purchase of the lot, construction, and getting their project through permissions. Since these can be difficult to estimate, risk assessments also have to be built in to costs. The numbers don’t always make it worthwhile, even when anticipated profit is less important (as for non-profit developers).

In practice, our simplified sequence is actually a bit more complicated. Developers often specialize in certain types of developments, and may as a first step seek out lots where these types are allowed to start looking for sales there, checking each sale for viability of redevelopment (2-1-3). If zoned capacity is tight speculative behaviour might emerge, where developers look at viability of redevelopment first and snap up likely sites when they go up for sale, speculating about the potential for upzoning in the future (3-1-2). Of note, these speculative behaviours can be avoided by providing ample zoned capacity, and providing it in location where housing demand is high, thus reducing the potential profit from as well as the need for speculation. New Zealand regulation, for instance, explicitly requires a competitive buffer be built into zoned capacity to keep land markets from tightening up and reduce speculation. (Ministry of Housing and Urban Development 2022)

Overcoming the inherent complexity to estimate the likely sale of a property for redevelopment requires a relatively sophisticated model, potentially informed by past data on property transactions and models of property values under current as well as redeveloped use, combined with pro formas incorporating redevelopment costs. (e.g. Romem (2022) or von Bergmann et al. (2023)).

Despite this complexity, a few takeaways are worth pointing out. In general, the more additional zoned capacity is added on a given site, the greater the possible profit to redevelopment. The greater the number of lots with additional zoned capacity, the more likely you are to get sales that lead to redevelopment. Similarly, the greater the number of lots with additional zoned capacity, the less competition between developers to buy those lots, driving down the price of land as an input to development. By contrast, concentration of additional zoned capacity across a narrow range of lots works in the opposite direction, driving up developer competition for the possible profit, inducing speculation, and driving up land as an input to development. Lack of zoned capacity forces developers to either turn elsewhere to build housing, or to engage in riskier, lengthier, and more expensive negotiations to rezone properties, driving down development overall.

With this understanding we return to our central question, what’s the minimal amount of zoned capacity for the housing market to function fairly freely? A reasonable answer might be to take one-and-a-half to two full development cycles as a minimum timeline, and take an estimate of the existing housing shortfall plus housing required for anticipated demand growth, as the basis for projection. This tells us how much housing we expect to get built in an unrestricted market. To be safe we want to take upper ends of the confidence intervals on the housing estimates. For the housing market to function freely we will want to add in a competitiveness margin to ensure that developers aren’t bidding up prices by having to compete for the same land. The appropriate size of this margin is difficult to rationalize, looking at what others have done we note that New Zealand chose 20%. (Ministry of Housing and Urban Development 2022) This would then be the minimum amount of economically viable and likely available zoned capacity to ensure a freely functioning housing market.

Recent Development by Zoning Type in Vancouver

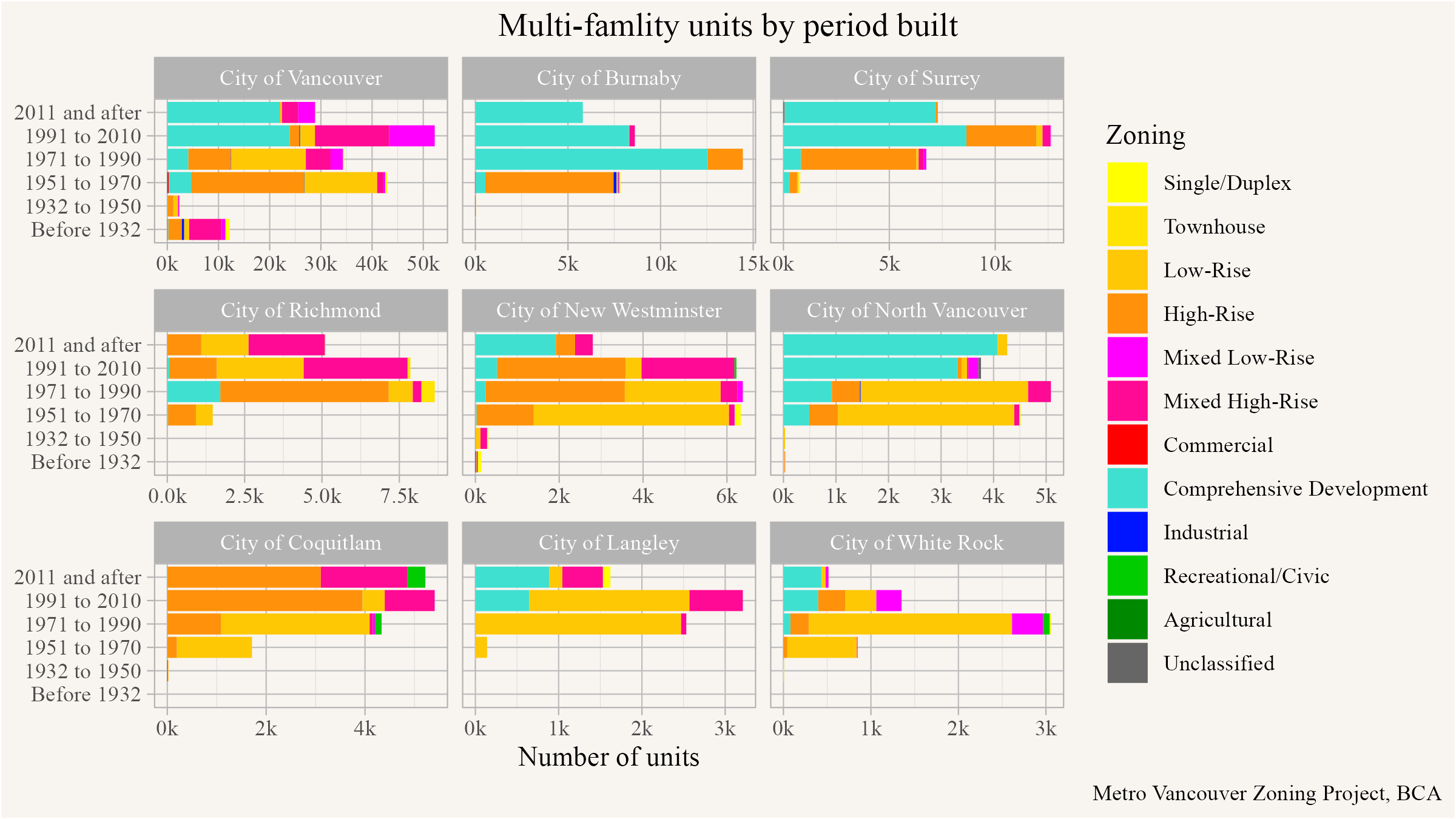

Drawing from our work codifying zoning codes up to 2020, we can take a look at how development has unfolded within the City of Vancouver, as well as some of its surrounding municipalities. Where has new multi-family housing gone by zone?

In accordance with our estimates of zoned capacity, there was practically no outright zoned capacity left for multi-family housing in the City of Vancouver (upper left corner). Low-rise and high-rise zoning meant to support multi-family housing was effectively all used up for development by 1991. Conditional zoned capacity for housing remained for lots within Commercial zones, and these have been intensively developed since 1991, coded as Mixed Low-Rise and Mixed High-Rise below. But most housing built since 1991 has been constructed on individually tailored rezoned properties, the most uncertain, time-consuming, and expensive pathways to redevelopment, coded as Comprehensive Development (CD) below. The same pattern of a shift to rezonings in response to declining zoned capacity for multi-family housing is also evident across the region, showing up clearly in Burnaby, Surrey, New Westminster, North Vancouver, White Rock, and even Langley. Richmond and Coquitlam have so far bucked the trend toward rezoning, but still show increasing reliance upon placing new housing in mixed-use commercial developments.

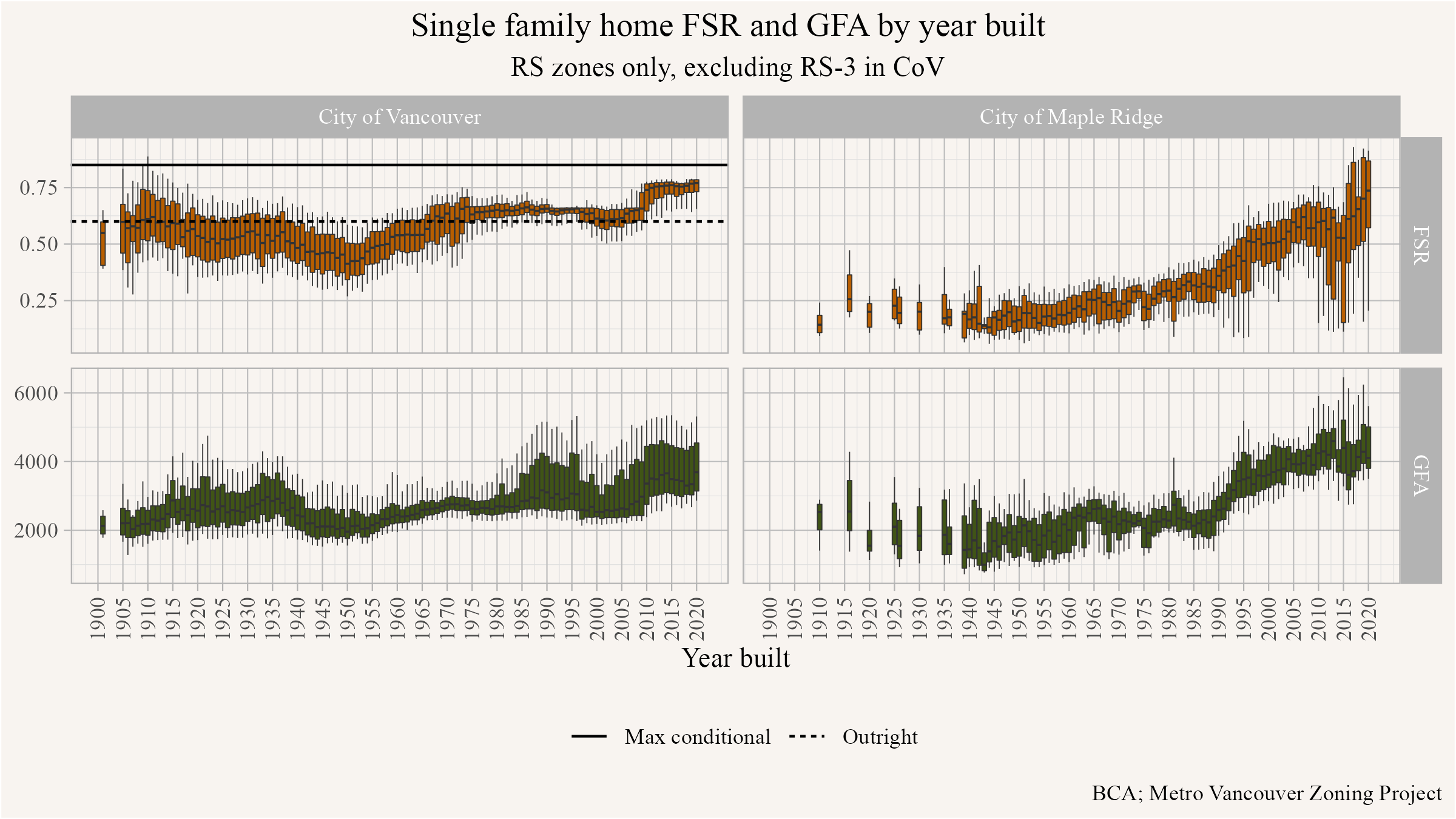

What about single-family lots? Recent provincial legislation was intended to enable multiplexes by right across most urban areas of the province. It’s not yet clear how this will be implemented by municipalities, and there are signs many will attempt to do as little as possible to add more zoned capacity in this way. In the meantime, we can look at how low-density housing developers have responded to floor space constraints within the zoning code over time. Here, too, there is evidence that they have increasingly built as much floor space as the City allowed, reaching zoned capacity for each lot without generally adding much in the way of new dwellings.

Estimating Zoned Capacity for 20 Years of Housing Need

Let’s return to our central question. How do we add enough room for housing to meet housing needs? In particular, how do we get enough zoned capacity to insure we’re meeting at least twenty years of housing need, assuming we have a working estimate of housing need?

There remain a variety of technical obstacles in estimating zoned capacity and how it could be operationalized for planning purposes. One obstacle is sorting outright from conditional uses in establishing what counts as zoned capacity. BC’s legislation has seemingly forbid “conditional density” from counting, that is density enabled conditional on provision of benefits to the City in exchange (a.k.a. density bonusing). But that leaves open the possibility that other conditional zoning, like with the City of Vancouver’s Commercial zoning, might still count, potentially still requiring multi-unit housing to continue to go through lengthy, uncertain, and expensive negotiations and development permitting processes before approval. Another obstacle is remaining uncertainty over whether zoned capacity will lead to development. And unfortunately recent history is a poor guide here, especially insofar as for many Metro Vancouver municipalities, the majority of development has not been enabled via outright or even conditional zoning, but rather reactive spot rezoning via Comprehensive Development, which makes it difficult to learn about development patterns moving forward from historical data.

While it’s tricky and complicated in practice, what we can do here is at least list the ingredients needed to estimate zoned capacity in a way that’s useful for planning purposes. To know if you have enough zoned capacity to meet a particular estimate of housing need would require:

- Zoning data that’s properly coded for the understanding what can be built on each lot. In principle municipalities have such data, although our work on the Metro Vancouver Zoning Project has shown that it’s much less clear if it’s coded in a form that’s legible and comparable.

- Data on the existing use of the property. In theory this is available from the BC Assessment Authority, but in practice there are issues, for example most purpose-built rental buildings don’t have information on the existing square footage of the building.

- A model of likelihood of sale of current properties. This can be idiosyncratic, as noted above, but could be built on a history of transactions, and possibly weighted by the development option (see below).

- A model of property values under current use. A shortcut to this may rely on assessed values from BC Assessment, but it might need adjusting if property markets move quickly or in cases like purpose-built rental buildings where assessments are based on the income approach instead of resale value.

- A model of values of potential redeveloped use. This is a bit more complex as it requires a model able to estimate the value of a hypothetical property that does not yet exist. Not just on one particular site but on every site across the city. The difference between the value of the existing use and the hypothetical redeveloped use is the development option. This is not dissimilar from the work that has been done modelling the potential provincial SSMUH and TOA impacts in BC. (von Bergmann et al. 2023)

- A model that takes the economically viable zoned capacity together with likely sales, the development option and historical redevelopment data to estimate the likelihood of development of economically viable zoned capacity. This is the only way to get at whether enough capacity has been zoned to enable meeting estimated needs.

- In the case of existing shortages that are to be reduced, a model of how supply effects impact prices and economic viability given expectations about demand, which recursively flows back into previous points in a way enabling calculation across twenty years of expected development.

In summary, it will be very challenging to arrive at useful estimates of zoned capacity for planning purposes in BC. From a technical perspective, the main missing ingredient is accurate information on zoning, the other parts have in principle been done in BC for other work. (von Bergmann et al. 2023) From a practical perspective the fact that some of the underlying essential data, namely property roll and sale data, is locked up provides a challenge that prevents efficient and open analysis. This amplifies concerns that there may not be enough expertise within municipalities to carry out these estimates in a reasonable way. Centralizing zoned capacity estimates within the province could be more useful, especially if facilitated by reform providing a provincial template for consistent zoning codes that municipalities could pick and choose from as they seek to reach housing need targets. It remains unclear why our province needs thousands and thousands of different zones while e.g. Japan, a country with 25 times the population of BC, is doing fine with just 12. And probably more important than just making it easier to understand zoned capacity, provincial or national zoning codes would increase certainty and transparency, reduce costs to build housing and increase competition in the developer market.

Of note, we have dealt mostly with the complexity of estimating zoned capacity. As laid out in earlier sections, zoned capacity also works at a lag and operates across multiple scales. The lag is effectively built into provincial requirements to plan ahead for twenty years, but there is little justification as to why this is the best way to think about lagged effects. Ideally zoned capacity is constantly being reevaluated, leaving lots of excess room to accommodate growth in response to shifting demand. The issue of how zoned capacity relates to multiple scales also remains. In particular, while zoned capacity is estimated (and controlled) at the municipal level, we expect its effects to be felt across regional levels. This is also an issue plaguing estimation of housing needs, of course. Neighbouring municipalities clearly affect each other in ways that are difficult to disentangle to assign individualized housing need targets or the zoned capacities required to meet them.

Conclusion

Recent legislation in BC correctly places lack of zoned capacity as an important cause of our housing crisis, and looks to reform how it works. In this, the province is clearly aiming at moving planning from what we’ve called our current spot-discretionary regime back into a planning for growth regime.3 Requiring municipalities to estimate their zoned capacities and fix them to 20 years of housing need has been joined to SSMUH and TOA legislation. SSMUH legislation in theory challenges the exclusion of multiplexes from low density zones, adding outright zoned capacity. At the same time the TOA legislation attempts to add capacity for development around transit stations, but the implementation details and if and how this flows into zoning have largely been left to municipalities.

The province also gave municipalities tools to allow them to actually zone for the development they want instead of relying on rezonings in order to extract financial or in kind contributions from developers going beyond DCC/DCLs, and they have created legislation that supports implementing tenant relocation policies at the Development Permit stage of the process instead of having to rely on rezonings for this. Additionally they have streamlined the rezoning process for projects that are compliant with community plans to remove some discretion.

When moving back toward the planning for growth regime, the concept of zoned capacity becomes useful again. And the province is incorporating zoned capacity back into planning processes. But given the history of spot-discretionary planning in some parts of BC with heavy reliance on discretionary planning processes, the checkered history of the usage of the term in Vancouver in particular, and the technical difficulties in usefully operationalizing this concept, it will likely be a bumpy road. Indeed, Vancouver is having a hard time even meeting very cautious and short-term housing approval targets. It makes sense for the province to continue a strategy of consultation with municipalities, but we suggest there are some red flags to be raised over leaving implementation to municipalities. That’s both because a) many municipalities appear to be actively working against the intent of the provincial legislation, and b) even if they weren’t, it has become very difficult for them to do the technical work required to estimate either their housing needs or their zoned capacity. To put it more succinctly, there’s still a devil at work in the municipal response, and that devil is all too likely to appear in the details, even where municipalities are doing their best to keep it out.

Appendix - recent usage of the term “zoned capacity” in the City of Vancouver

The usefulness of the concept of zoned capacity hinges on the way development is carried out. With the downzoning in the mid-70s the City of Vancouver transitioned into the spot-discretionary planning regime and started to increasingly rely on one-off spot zoning and discretionary conditional zoning for growth. In this planning regime zoned capacity was reduced to a minimum in order to control development. The (former) RS and to some extent the RT zones where secondary suites and laneway houses could be added, if often conditionally, offered a bit more of a nod to zoned capacity. But overall the shift to a spot-discretionary regime fatally compromised the very concept of zoned capacity, and discussions around zoned capacity in the City of Vancouver have accordingly become confused and erratic. Neither council, nor staff, nor the general public seem to have a clear understanding how to approach the concept.

Zoned capacity estimates by staff, pegged at October 1996 and discussed in a report to council in 1998, do try to estimate build-out under existing zoning, but also include development potential they envision on sites that currently have no zoning for residential use in place. (And projections of how much population growth can be accommodated are hopelessly naive and certain to generate severe housing shortages if taken at face value. (von Bergmann and Lauster 2022))

In the years that followed, council often tried and failed to get zoned capacity estimates: (Woodsworth Tuesday, January 18, 2011) (Motion by Councillor Carr February 14, 2012) (Motion by Councillor Hardwick).

The starting point of the broader public zoned capacity discussions was probably a consultant report from 2014 that showed up in an administrative council report in the June 2, 2015 council meeting, as well as the 2019 follow-up report. Here we won’t comment on the report, and how it handled the question and tried to identify causal system-wide effects of CACs, but direct attention to the zoned capacity estimates in the report being based on staff estimates that explicitly include developments in principle contemplated in community plans with no actual zoning in place to support them. As source for estimates, the report cites the City of Vancouver, breaking out the following Development Potential reproduced in Table 1.

The 2019 report on the same topic updates the estimates of Development Potential, shown in Table 2 and again attributed to the City of Vancouver, and while it walks back some of the more egregious conclusions found in the first report, it still struggles with basic economics.

| Type | Units |

|---|---|

| Source: City of Vancouver; Note these figures are the City’s estimate of residential capacity by zone to 2041; there is additional residential capacity beyond 2041 in these zones. | |

| Estimated capacity in Existing Multifamily Zoning Districts | 43,100 |

| Estimated capacity in Recently Approved CD-1 Districts (approved since 2009), net of unit completions | 5,725 |

| Estimated capacity in ODPs, Community Plan Areas, and Policy Statement Areas | 46,388 |

| Total | 95,213 |

The numbers on capacity in existing multifamily zones are difficult to reconcile with reality, and we guess that the City was counting potential development in commercial zones, in particular in C-2 zoning. The bulk of the capacity explicitly required a rezoning. Despite this, the report and the subsequent public discussion frequently referred to the totals as zoned capacity.

The 2019 consultant report does acknowledge some of the difficulties with the development capacities it presents:

- A large part of the 43,000 unit capacity in existing zoning districts should be regarded as “paper” capacity that is not all readily available for development in the short term. Much of this capacity is “unused” density on sites that have already been developed and are not economically viable for redevelopment. For example, there are existing 3 storey residential buildings in locations zoned for 4 storeys. Until these properties redevelop, which may be many years in the future depending on the condition of the existing buildings, the unused zoning capacity exists on paper but is not practically available. If for illustrative purposes we assume that only half of this “paper” capacity is available for development in the short term, then the available total capacity is about 74,000 units or 19 years at the recent rate of development.

- In order to avoid even more upward pressure on land value, the market needs significantly more capacity than will be developed in the short term.

- Planning for significant increases in capacity takes years in Vancouver. The entire three-phase Cambie Corridor plan, focused on the Canada Line, took 10 years. Rezonings consistent with the plan have already occurred, but many of the sites are still in the approvals process.

Staff, including former head planner Gil Kelley, have at times made strong assertions about having enough zoned capacity, while at other times Staff have made some rather crude attempts to explain that zoned capacity is not a useful concept, as they did again in response to the motion by Councillor Hardwick.

These difficulties with talking about zoned capacity should not surprise, given the incompatibility of zoned capacity with the spot-discretionary planning regime. The City’s alternative concept of Development capacity can be understood as relating to economically viable and realistically expected to turn over zoned capacity in that it estimates expected future development, where the target is not the context of a freely functioning housing market or provincially defined housing need, but that of an informal quota set by regional planning. (von Bergmann and Lauster 2023b)

References

Footnotes

In practice restricting what can be built in some locations and trying to shift development to other areas does sacrifice some value and growth. Location matters.↩︎

This is something the province could (and should) change, as we have argued before there are large benefits to making this data openly available that far exceed the benefits of being able to sell this data, the main reason why it remains locked up for general public use.↩︎

see von Bergmann and Lauster (2023b) for details on these terms.↩︎

Reuse

Citation

@misc{zoned-capacity-promise-and-pitfalls.2024,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens and Lauster, Nathan},

title = {Zoned {Capacity} - Promise and Pitfalls},

date = {2024-05-31},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2024-05-31-zoned-capacity-promise-and-pitfalls/},

langid = {en}

}