Recently the City of Vancouver pivoted their planning for RS (“single family”) and RT (“duplex”) neighbourhoods from downzoning, to slow the pace of teardowns to adding infill as an incentive to to keep older buildings through extensive renovations, to now proposing the Making Room program to allow stratification and higher unit density, and Mayor Robertson adding an amendment to direct staff to look into also allowing multiplexes.

This change in policy grew out of a series of consultation processes, and it is quite interesting to browse through them chronologically and observe the shift in how participants talk about low density zoning.

Change is hard, and public opinion is by no means uniform in their views. Making Room if facing fierce opposition in some quarters, all the while there are those, including myself, that are arguing it does not go far enough.

Today the first part of Making Room is headed to council. The changes associated with this are small, but have symbolic importance. The RS zoning documents start out with the sentence

The intent of this Schedule is generally to maintain the single-family residential character of the RS-1 District

and the goal is to change this “to better reflect the form of development in those districts”, i.e. that we already allow multiple dwelling units on all lots in Vancouver.

The second important change is to remove the mandate on “poor doors” in RS zoning. Right now, a “single family” home can only have one front door, the door to the secondary suite must not be visible from the street to maintain the “single family character”. This is partially symbolic, but it also paves the way to properly design for two dwelling units within the “single family” home, making secondary suites more livable.

More important changes are headed to council later this year, with more to come after the election.

We would like to take the opportunity of today’s council meeting to look at the data on how people currently live in low-density zoning.

Population growth

The essence of Making Room is to allow more diverse housing types. Right now what’s legally allowed to be built in RS zones is a “single family home”, possibly with a suite and a laneway house. Suites can’t have front-facing doors in order to preserve the appearance of a “single family” neighbourhood, and the laneway house is restricted in size to about 700 square feet on regular sized lots. That means we allow a maximum of 3 units per lot, when we check our building stock we see we have on average a little less than half that. When it comes to suites we are close to equilibrium, with permit data indicating that we are building them at rates only slightly above the freqency of suites in the overall stock. We have been building around 400 laneway homes a year. Combined this has been barely enough to keep population in RS zones stable, with the east side of RS in Vancouver slightly gaining and the west side slightly draining population.

So when it comes to accommodating the population growth in the City, RS (and RT) are our deadbeat areas, whereas the multi-family areas pick up all the slack and accommodate the entire population growth. With RS, RT and FSD zones taking up 77% of residential land use, we are forcing all growth into the remaining 23% of residential land. Which forces us to build tall. And increasingly tear down smaller multi-family to make room for larger multi-family.

At the same time, we are aggressively renewing our single-family building stock without adding (significant) units, which leads to the City of Vancouver’s very ineffective construction process, where we tear down 1 unit for every 5 completed. And this does not only mean that we have to subtract one fifth of units from completion data if we want to talk about net new units, it also leads to unneccessary carbon emissions as we accommodate growth inefficiently.

Making Room asks low density zones to make room for our growing population by allowing new buildings to contain more units and accommodate more households. This helps improve the ratio of demolitions to completions and thus also reduce carbon emissions.

Complex households

There is a lot of talk about the current “single family” building stock accommodating multi-generational households. Children might move out of their parent’s home, but some come back after forming their own families and live on their parent’s property. Either in a secondary suite or a laneway house, or sometimes switching roles with their parents depending on family needs. This can be mutually beneficial, and there is some variation across cultures in it’s prevalence.

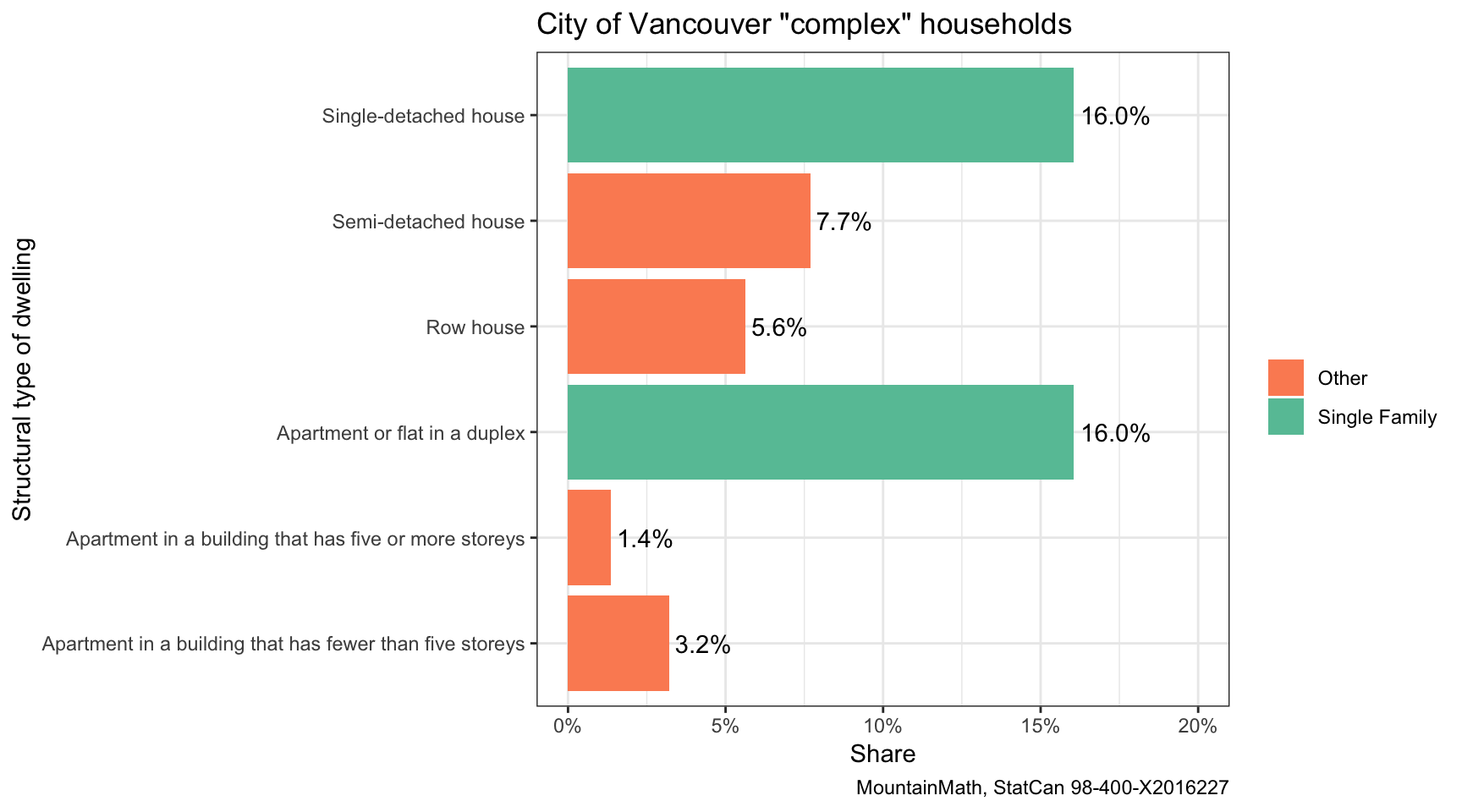

Next to multi-generational households, we have more general multi-family households and other forms of “complex households”, for example couple family (or lone parent) households (with or without children) with additional unrelated persons in the household. For the purpose of this section we want to focus on these “complex” households, while excluding roommate type households (two-or-more person non-census-family households).

Making Room asks to also allow other ways to split up homes and allow stratification and designing for multiple separate units. While current zoning allows for three units on a lot, it does not allow for three equal units.

An interesting question is how many “complex households” there are in “single family” homes, and how has this evolved over time.

We see that 16% of households in both single detached, as well as suited single detached (“duplex”) units are “complex households”, which is a sizable share. Again, this includes multi-family households, as well as family households with unrelated persons. Is 16% high enough to justify mandating the current form of single ownership “single family” homes? Making Room would not disallow the use of homes as multi-family homes, and it would not disallow building new homes to fit that model. All it does allow to also build and design for other uses that would prefer to split up homes into smaller owenrship portions.

Geography of mutiple-census-family households

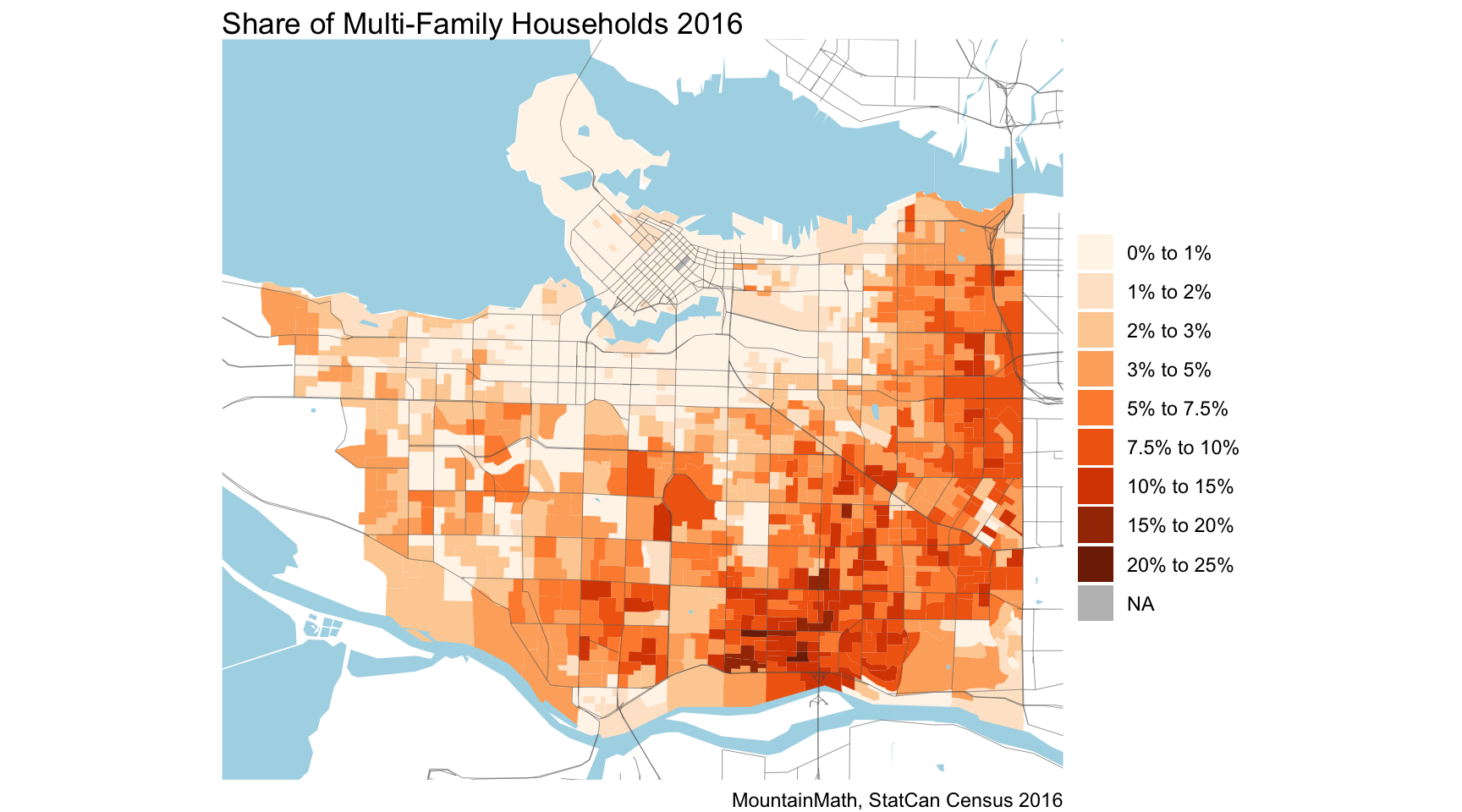

Looking at the geography of multiple-census-family households (skipping census family households with persons not in the census family that we aggregated into “complex households” above) can give us more information on where these households live.

As expected, multi-family households are more prevalent in the “single-family” areas on the east and south side of Vancouver. We can derive further insight by looking at the change in the share of multi-family households over the past ten years.

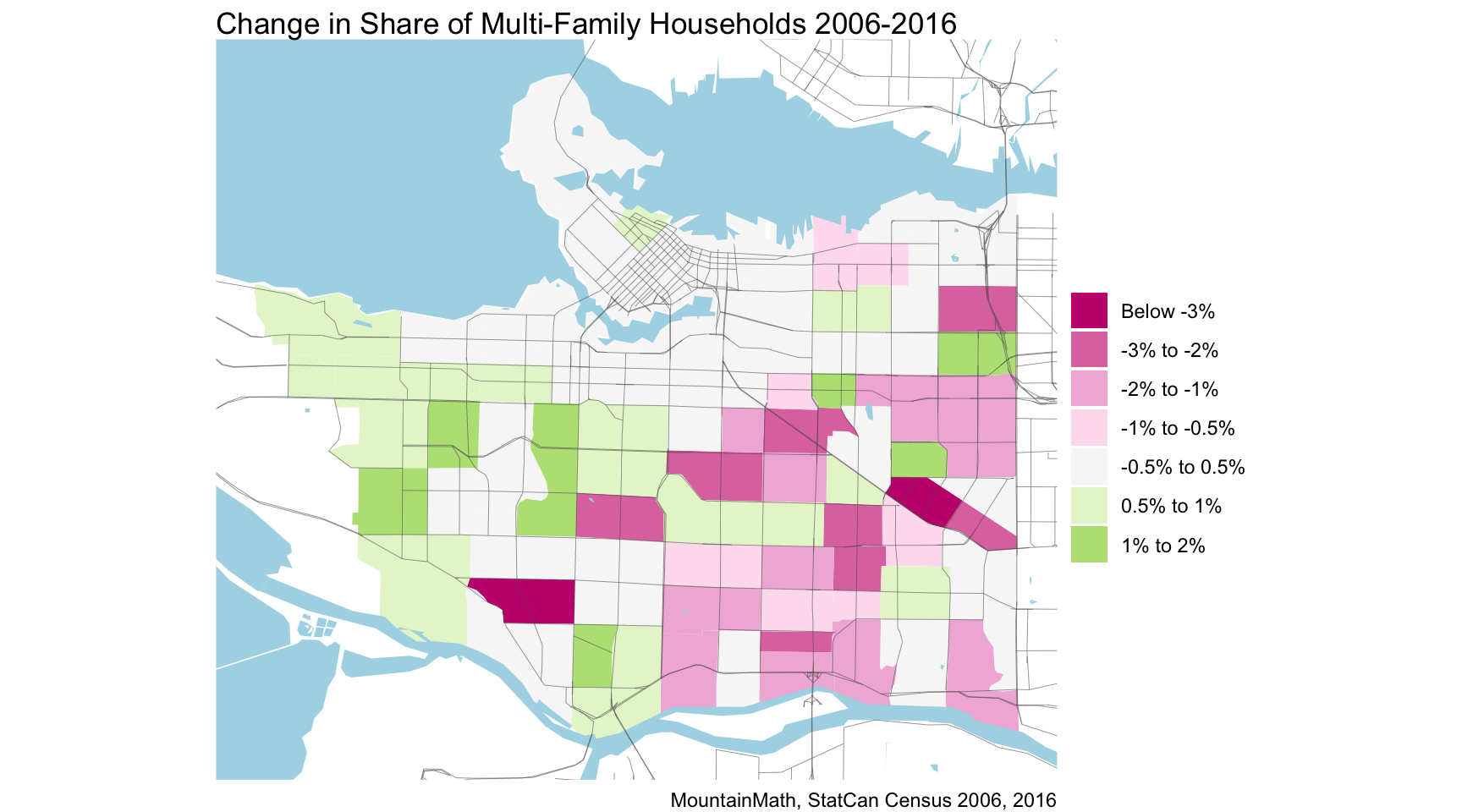

Overall, the share of multi-family households decreased slightly from 2.82% of households in 2006 to 2.53% in 2016. We have seen that multi-family households cluster geographically, and we can check how the geographic distribution has changed over time.

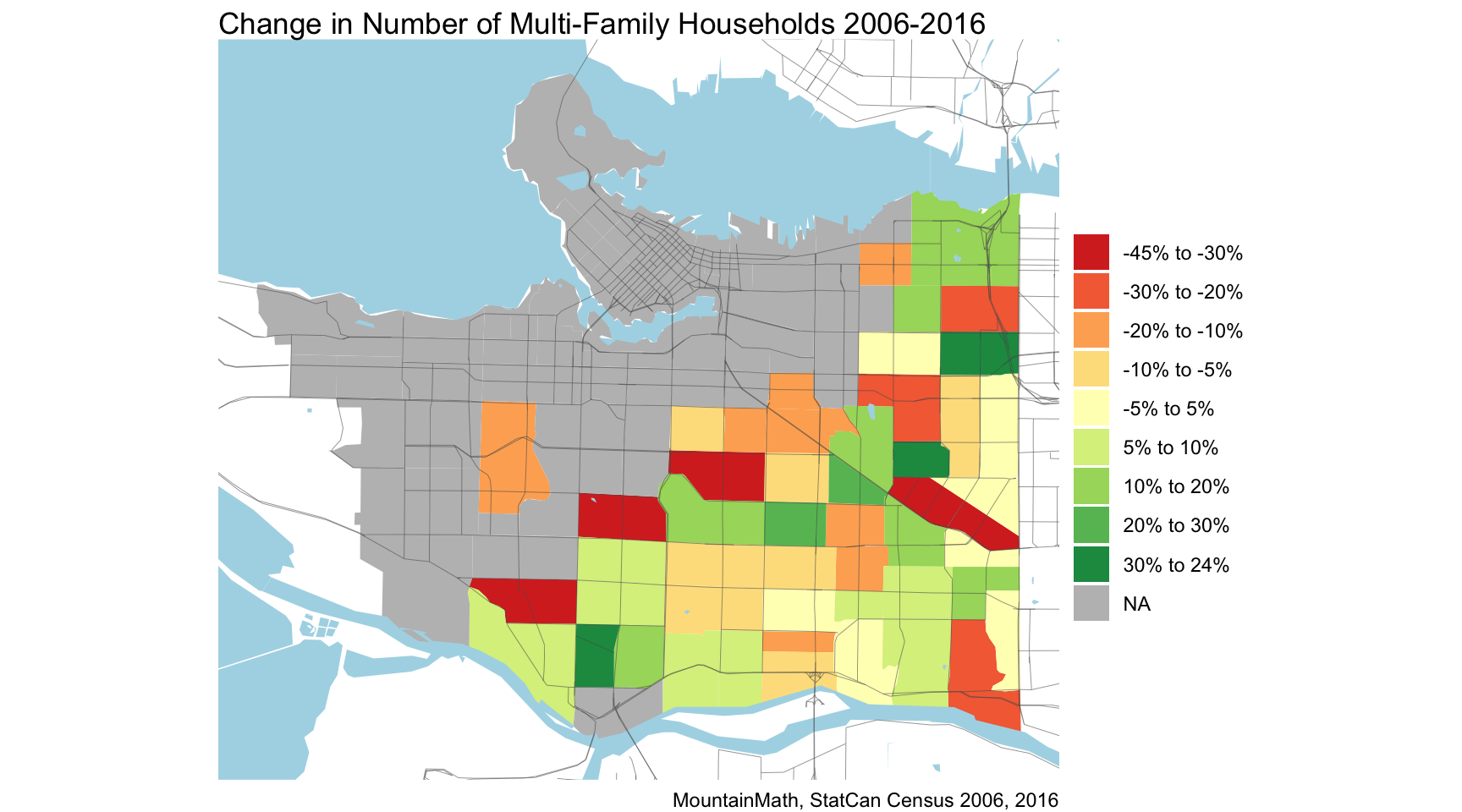

Surprisingly we see that the share of multi-family households generally declined on the east side and and increased on the west side. The change in share can be confounded by an increase in the number of households, we can also look at the change in number of multi-family households to get a different view on the change, greying out areas with fewer than 50 multi-family households in 2006.

This only gives data on the east and south side areas, but it shows that increasing number of household has masked an actual increase in the number of multi-family households in some areas.

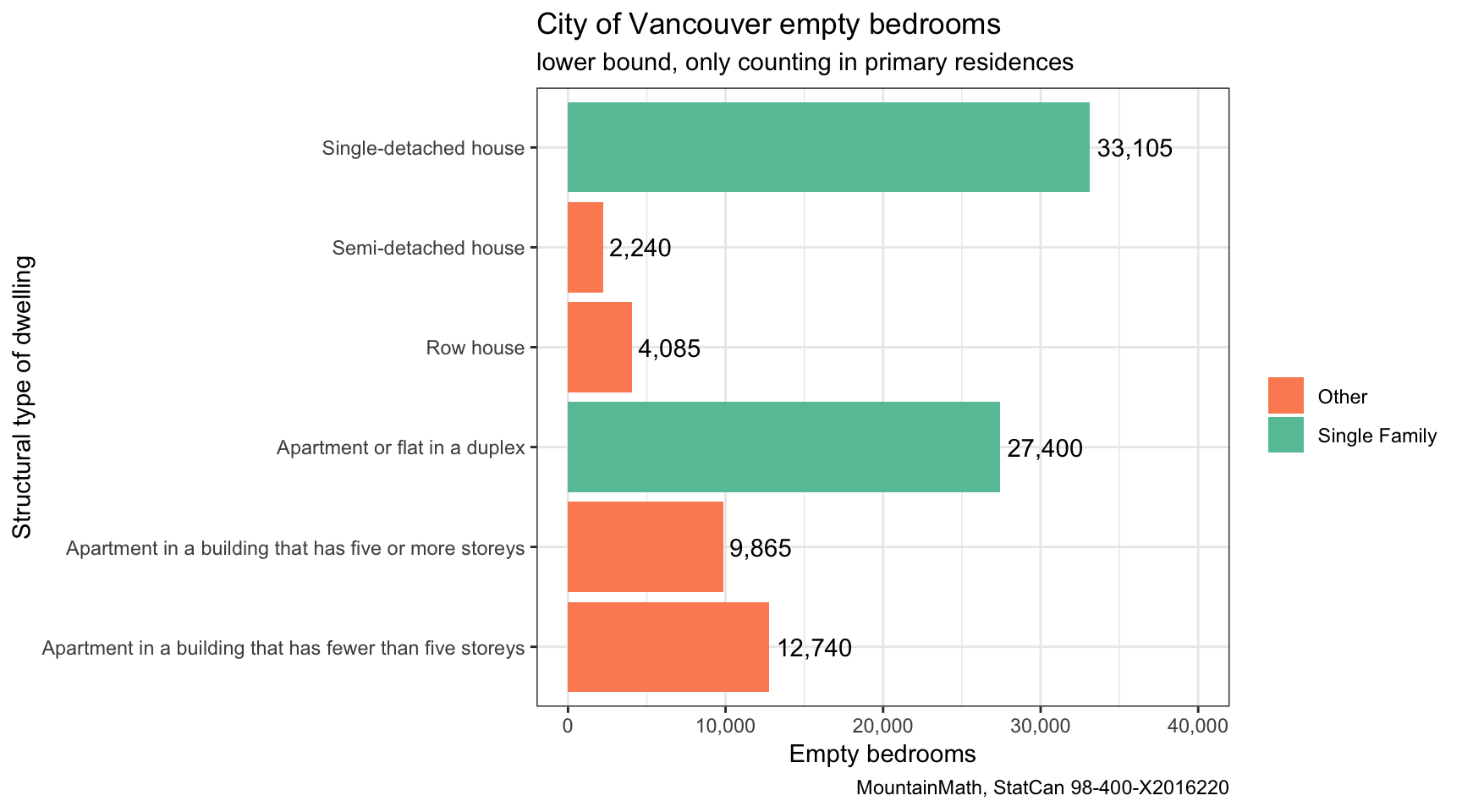

Empty bedrooms

Vancouver has seen lots of discussions on empty homes. We read in the news how “unoccupied or under-utilized” homes should return to the market and be made available for purchase or long-term rental. Which is a good short-term initiative to increase the supply of available housing units, and at the same time ease worries about new buildings remaining empty. Here “under-utilized” refers to the the temporal nature, where for example a vacation home may only be occupied for a short period during the year. But homes can also be “under-utilized” if they have more bedrooms than the household requires. It is virtually impossible to ensure optimal utilization of homes, often considerable time passes after children move out and leave bedrooms empty until parents may (or may never) downsize. People purchase homes with additional bedrooms in anticipation of a growing family. Some people simply like and can afford to have extra bedrooms in their home in case of visitors or for other purposes.

But during a housing crisis, where we are comfortable to penalize units that are “under-utilized” temporally, we have to ask ourselves why we mandate “overhousing” through zoning that has the effect of forcing homes with more bedrooms than needed. Just to be clear, Making Room does not disallow overhousing, or restrict the number of bedrooms that could currently be built. But it allows homes to be subdivided (and stratified) into units that are right-sized.

To measure the degree of “overhousing” we can count “empty bedrooms”. For this we give each person in a household their own bedroom. We could go a bit further and assume couples share a bedroom like we have done in this interactive map, but for this purpose we want to keep it simple. That means for example that we count a couple household with 1 kid to have no extra bedrooms if they live in a home with three or fewer bedrooms. We count studio apartments as 1 bedrooms here, and the other assumptions around large number of bedrooms or large household size are engineered to under-estimate the count of empty bedrooms. For details check out the code.

So how many empty bedrooms are there in low-density zoning? The census can’t quite answer than, but it can answer how many empty bedrooms there are in low-density housing units, the vast majority of which are situated in low-density zoning.

The result is really quite telling. Out of the 89,435 extra bedrooms, 60,505 of which are in “single family” homes. And this is not counting bedrooms in unoccupied or temporarily occupied homes (or suites).

As an aside, we can also split the count of empty bedrooms by tenure. It should not surprise that renter households tend to be overhoused much less frequently with 3.16% of renter households having extra bedrooms versus 15.2% of Owner households across all structural types of dwellings.

Part of that is confounded by owner households being over-represented in “single family” homes, but even when just looking within single detached (so unsuited single family) homes we have 12.8% of renter households overhoused versus 25.6% of owner households.

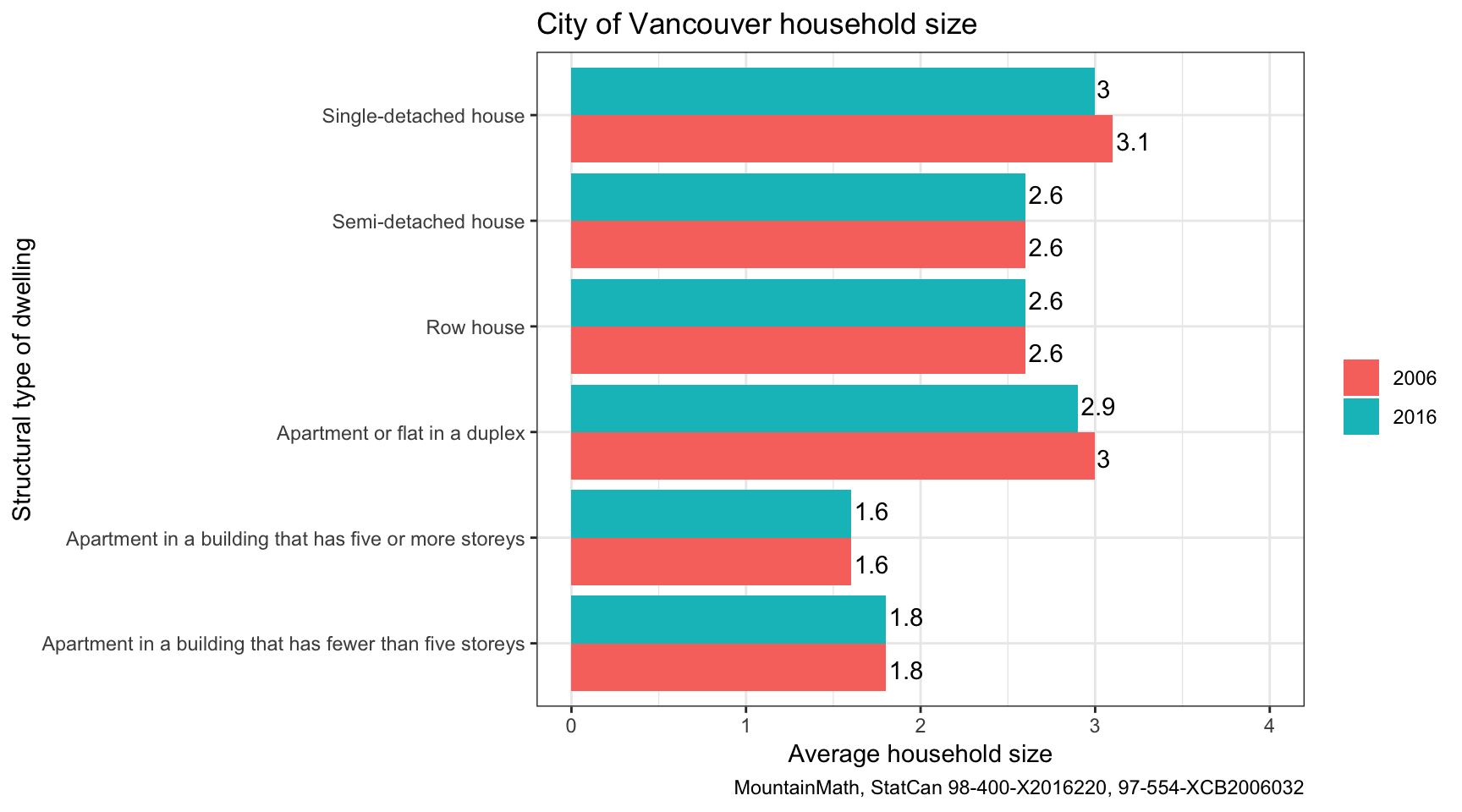

Household size

A related dimension is that of household size. We can compare how the average household size has changed since 2006 by structural type of dwelling.

This shows that both Single Detached and Duplex (a.k.a. suited single detached) units have seen a drop in household size, while household size has remained constant in the other dwelling types.

This shows that overhousing has been increasing in these dwelling types.

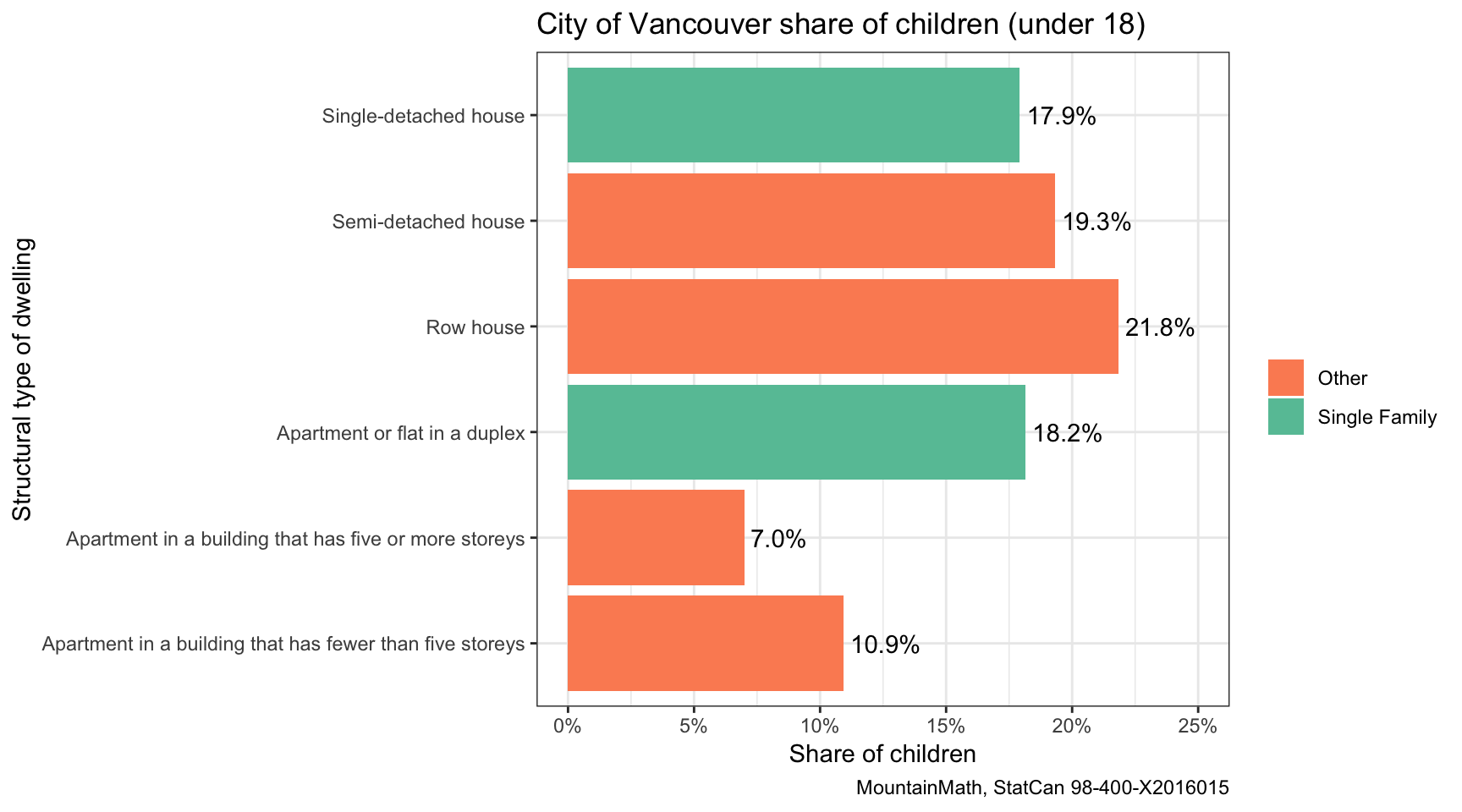

Children

“Single family” zoning emphasizes “family”, which in people’s minds usually means “family with children”. One question we can ask is what portion of people are children in each dwelling type.

The results are quite surprising, at least to us. Row/Townhouse and Semi-detached (commonly referred to as “side-by-side duplex”) dwelling units have the highest share of children, followed by suited “single family” homes (“duplex”) and single detached homes. Unsurprisingly, the share of children is much lower in apartments, with low-rise registering with a higher share of children compared to taller apartments.

If accommodating families with children is one of the priorities, then Making Room is moving in exactly the right direction in that regard.

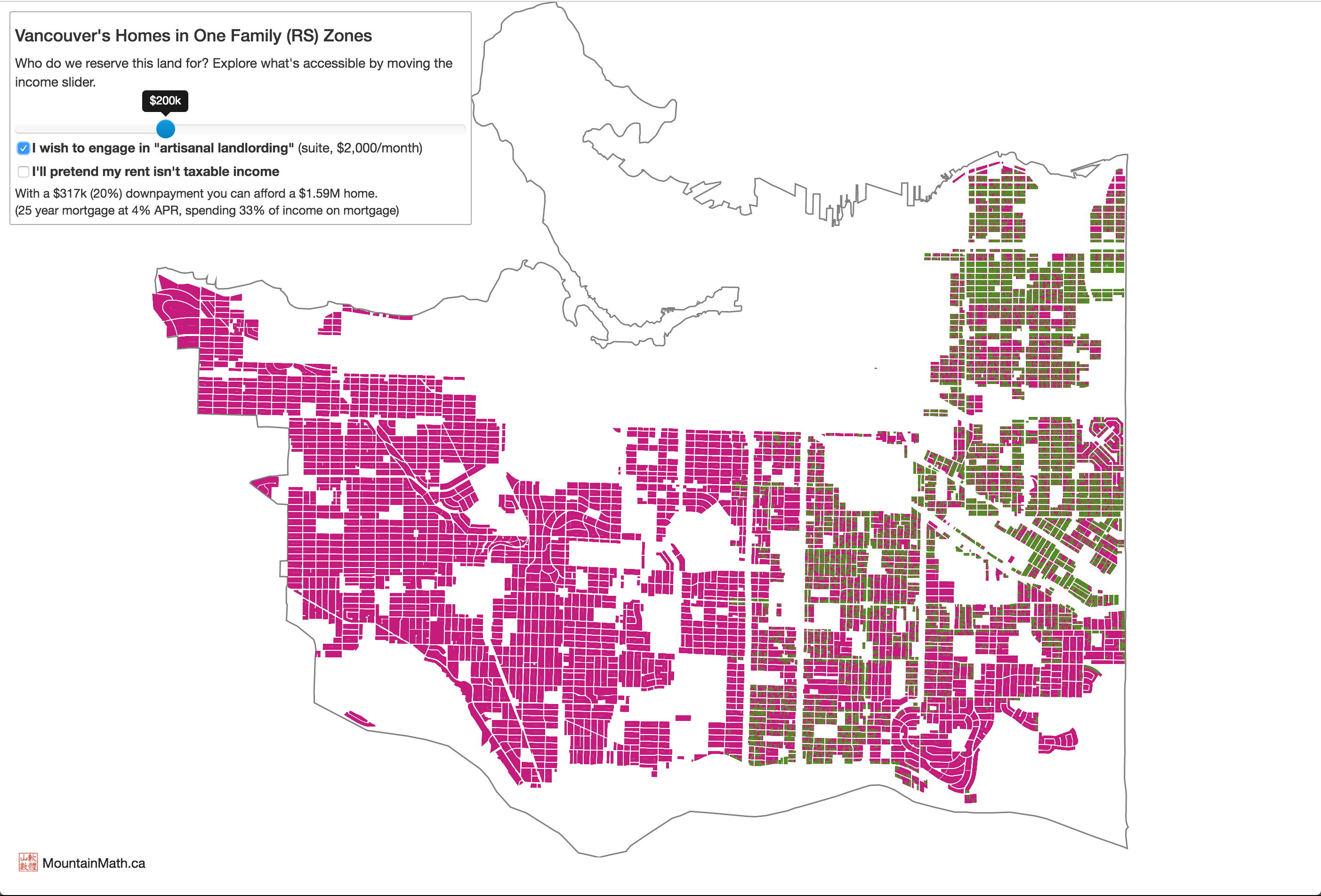

Affordability

Ownership in low-density zones has been rapidly moving out of reach for the majority of Vancouver families, which begs the question who is served by maintaining low-density zoning.

Ownership in low-density zones has been rapidly moving out of reach for the majority of Vancouver families, which begs the question who is served by maintaining low-density zoning.

Making Room proposes to allow stratification of housing units, which in principle gives the option of either buying the traditional “single family home” and renting out a suite, or stratifying the suite as a separate unit (assuming compliance with building codes) and only buying one of the two. Looking at how this plays out in Mount Pleasant RT zones where we have been allowing stratification and multi-plexes in connection with character retention and infill we see that this can substantially lower per-unit cost while only slightly inflating land values.

Making Room is bound to lower the bar of entry into low-density neighbourhoods. And reduce debt levels, the best mortgage helper is a lower mortgage (so stratifying the suite and selling it separately instead of taking on more debt and renting out the suite). But we are starting off from really high unafforadbility levels, moving to duplexes will make it still challenging to again be affordable to average families. Median incomes of City of Vancouver families with children was $112k in 2015. Building stock will take time to turn over and adapt to new regulation, most of the stratified duplexes coming out of this process will be new stock and thus more expensive. Moving beyond duplexes to multiplexes will further increase options and probably reach the majority of Vancouver families with children, we will have to do more analysis or wait for the staff report to quantify that.

So does Making Room go far enough to restore basic levels of inclusivity in Vancouver? I don’t think so. We have seen how low income residents have gotten pushed out of City of Vancouver proper, with the top income brackets registering very strong growth. At a rate that’s noticeably higher than Metro or Canadian averages. Median incomes in the City of Vancouver used to lag the City of Toronto in 2005, but in 2015 City of Vancouver came out on top of City of Toronto. Inflation-adjusted average City of Vancouver home values have increased 89.1% 2006 to 2016, average inflation-adjusted ownership costs have increased 16.2% and average inflation-adjusted rent has increased 21.3%. At the same time, inflation-adjusted average family incomes have increased 16.3%.

This is reflected at the individual household level in that the share of shelter-cost-burdened households, those paying more than 30% of income on housing, has decreased 2006 to 2016. And this still holds true when running this separately for renter and owner households.

So affordability actually increased using the CMHC 30% of income on shelter metric, due to strong income growth, self-selection in migration patterns by wealth and income, and tighter distributional matching of incomes to housing costs. The losers in the process are those without access to wealth, high income or both. It will take time to reverse some of this development. This will require a massive investment into public housing, as well as lowering the entry-point to market housing. Making Room works on that latter part, and ideally it can get expanded to higher density of maybe 6 units per lot to reach further down the income distribution. At the same time we need to find ways to address the lower ends of the income distribution that the Vancouver market simply won’t be able to serve, even if the market corrects somewhat.

The city has been working of subsidized rental models via inclusionary zoning, and providing land for alternative ownership models. The province and the federal government are starting to take their role in the public housing sector more seriously. But it will take more than what is currently being offered to undo the results of decade-long inaction on the public housing front.

Upshot

The data of how low-density housing is getting used points toward the Making Room initiative going in the right direction. There are many factors contributing to Vancouver’s affordability problem, the abundance of low density zoning close to the centre of our metropolitan area is an important one. Many Vancouverites look with envy toward Vienna for their affordable housing, but often neglect that, among other important differences, Vienna does not have low density areas so close to the city centre like Vancouver does.

As usual, the code that made this post is available on GitHub, including for gathering the required data, generating the graphs and all numbers quoted in the text. Feel free to download it to reproduce or adapt for your purposes.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{making-room.2018,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Making {Room}},

date = {2018-07-17},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2018-07-17-making-room/},

langid = {en}

}