Down south of the border, a politician who shall remain nameless campaigned on “draining the swamp” of Washington D.C., trafficked in countless conspiracies, and lied his way into office. His lies painted a picture of a United States turned dark, corrupt and menacing. He promised to fix it, Making American Great Again, mostly by shutting down globalization and kicking out the immigrants.

In Canada, we like to think we’re immune to this kind of rhetoric. But a strain has made its way into discussions concerning Vancouver, where the intersection of real estate, politics, and globalization are increasingly portrayed as a swamp in need of draining. We don’t believe most of those portraying Vancouver as swamp-like are intentionally lying (and in real life they surely favour the preservation of environmentally sensitive wetlands). Nevertheless many commenters are muddying the discourse with poorly sourced claims as a means of scoring political points and attacking various aspects of globalization.

It’s tricky to track down the spread of all the false claims out there. Fortunately a bunch of them were concentrated in a recent piece on “Dirty Money” in Macleans by Terry Glavin that views Vancouver as “a case study in the dark, broken and ugly side of globalization.” Recognizing that getting facts and interpretations right is often difficult for even the most well-intentioned, let’s work toward correcting a few misperceptions, line by line:

“At least 20,000 Vancouver homes are empty, and nobody’s really sure who owns them.”

Variations of similar statements permeate the media, with various degrees of factual accuracy. The most common misrepresentation is to refer to the 25k homes not “occupied by usual residents” as “empty”, which the above quote avoids by using an appropriately lower number.

The main issue with the above quote is that it’s portraying those “at least 20,000” homes as problematic vacancies, neglecting that that count includes moving vacancies around census day, empty suites (about 4000 of them), and units in buildings that completed around census time and did not have the time to fill in yet.

Accounting for these types of vacancies, we arrive at the ballpark of the Ecotagious Study based on BC Hydro data that found between 10,800 (for year-long vacancies) to around 13,500 (for four-month vacancies) and now the 8,481 empty homes through the empty homes tax declarations, although some of those empty homes found via the EHT are outside of the universe Ecotagious reported on.

When quoting these numbers, the key question is what are the numbers supposed to be used for. If it’s to highlight “problematic” vacancies, then the Ecotagious numbers probably get us the best estimate for that point in time. Since then the number has likely dropped due to Empty Homes Tax pressure, we will have to wait until the repeat of the Ecotagious study to get confirmation on by how much.

And the reason we don’t know who owns them is not for some nefarious reason but simply because the methods we have for estimating empty homes (other than the ones caught by the Empty Homes Tax) do not allow for the identification of units.

“Another 25,000 residences are occupied by homeowners whose declared taxable household incomes are mysteriously lower than the amount they’re shelling out in property taxes, utilities and mortgage payments.”

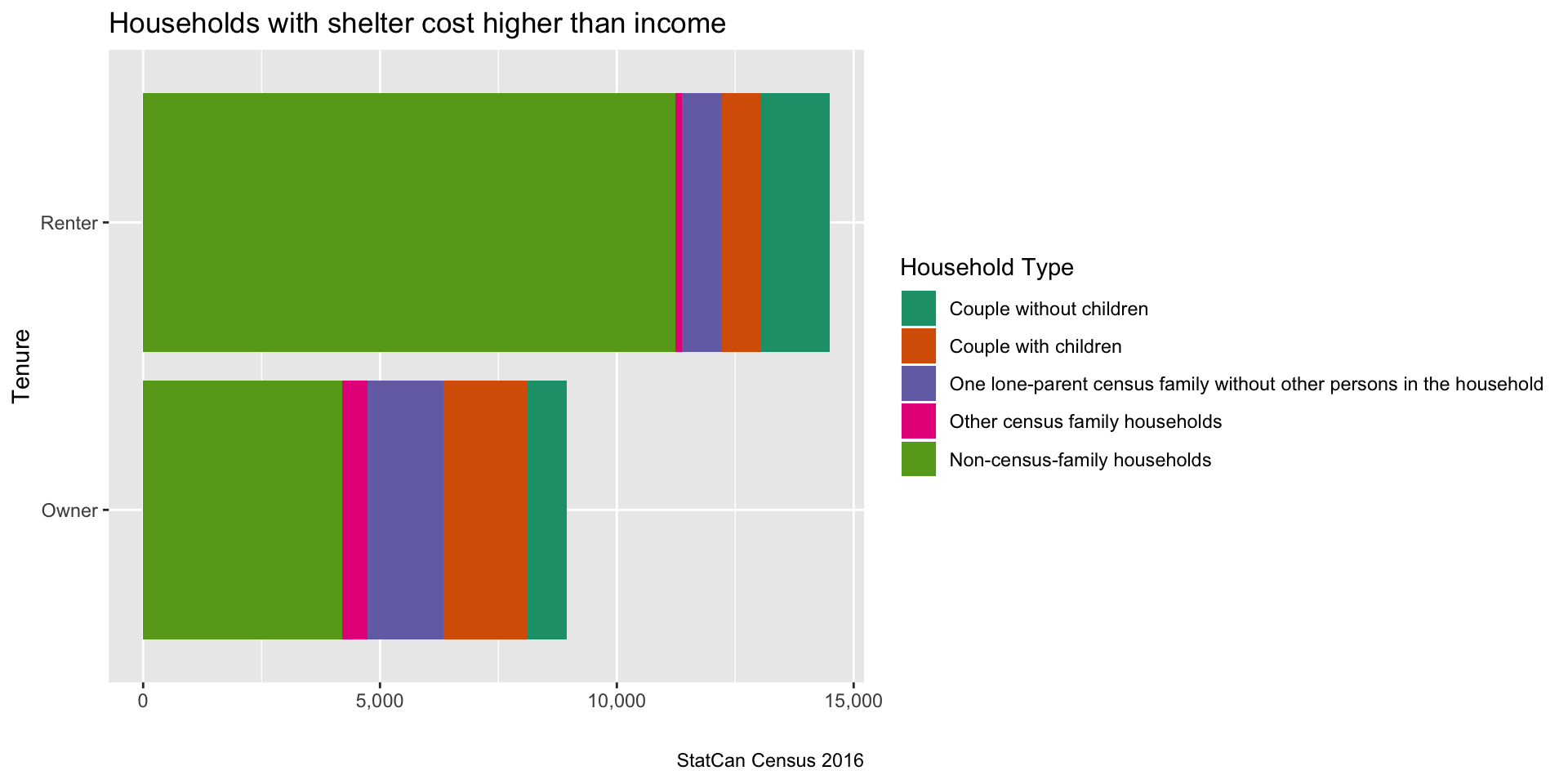

That’s plain false, we have looked at this before. The 2016 census counted only 8,940 owner households with higher shelter costs than income. An additional 14,510 renter households paid more than their income in rent and utilities, making for a total of 23,450 households in the City of Vancouver that had higher shelter cost than income, most of which were renter households.

The wording of the sentence, followed by the next talking about tax avoidance in British Columbia real estate, seemingly suggests that the majority of these 23,450 households were cheating in some way. Let’s take a closer look at these households with shelter cost higher than income.

One of us (Jens) is partially responsible for bringing this stat into circulation and failing to provide more extensive context from the get-go.

Looking more closely, we see that the bulk of these households are non-census-family households, probably roommates in many cases. Students likely account for a lot of the data. Single parents are also common. While there are some indications of irregularities in the data worth investigating further, broadly suggesting all these households are tax cheats is irresponsible.

“Non-residents own roughly $45 billion worth of Metro Vancouver’s residential properties, and non-residents picked up one in five condominiums sold in Metro Vancouver over the past three years.”

The first part is fairly accurate, CHCP reports that $43 billion worth of residential properties in Metro Vancouver were owned by non-residents. Of course that’s less than 5% of the total value of $884.50 billion.

The second part is a prime example of making statements without understanding the data. We don’t have data on non-resident buyers, presumably referring to buyers with primary resident outside of Canada at the time of the sale.

Considering similar statements in an earlier article by the same author, our best guess is that the author was referring to non-resident owners of condos that were built between 2016 and late 2017. Owners of recently built condos could be taken as a proxy for buyers if one makes some assumptions on resales.

Except the ratio of condo units built between 2016 and late 2017 that were held by non-resident owners is one in 7.1 for Metro Vancouver, and for the City of Vancouver that the previous article was referring to the ratio is one in 6.5. (CANSIM 33-10-0003)

In summary it seems the original statement is the product of playing loose with definitions, Metro vs City mixup and aggressive rounding to pump up the numbers.

“But Transparency International reckons about half of Vancouver’s west-side residences are owned by mystery trusts or shell companies.”

Big if true, a claim so outrageous that it needs data to back it up. It seems that this is based on a transparency international report that the author also referred to in a February column, where the author characterized this as “Transparency International estimates that perhaps half of Vancouver’s high-end residences are now owned by shell companies or trusts”. Now this has morphed into “about half of Vancouver’s west-side residences”. It’s good to remember what the Transparency International study actually did, it looked at the 100 most expensive properties in Metro Vancouver and found that 46 of these were owned by companies or trusts (not all of which have opaque ownership).

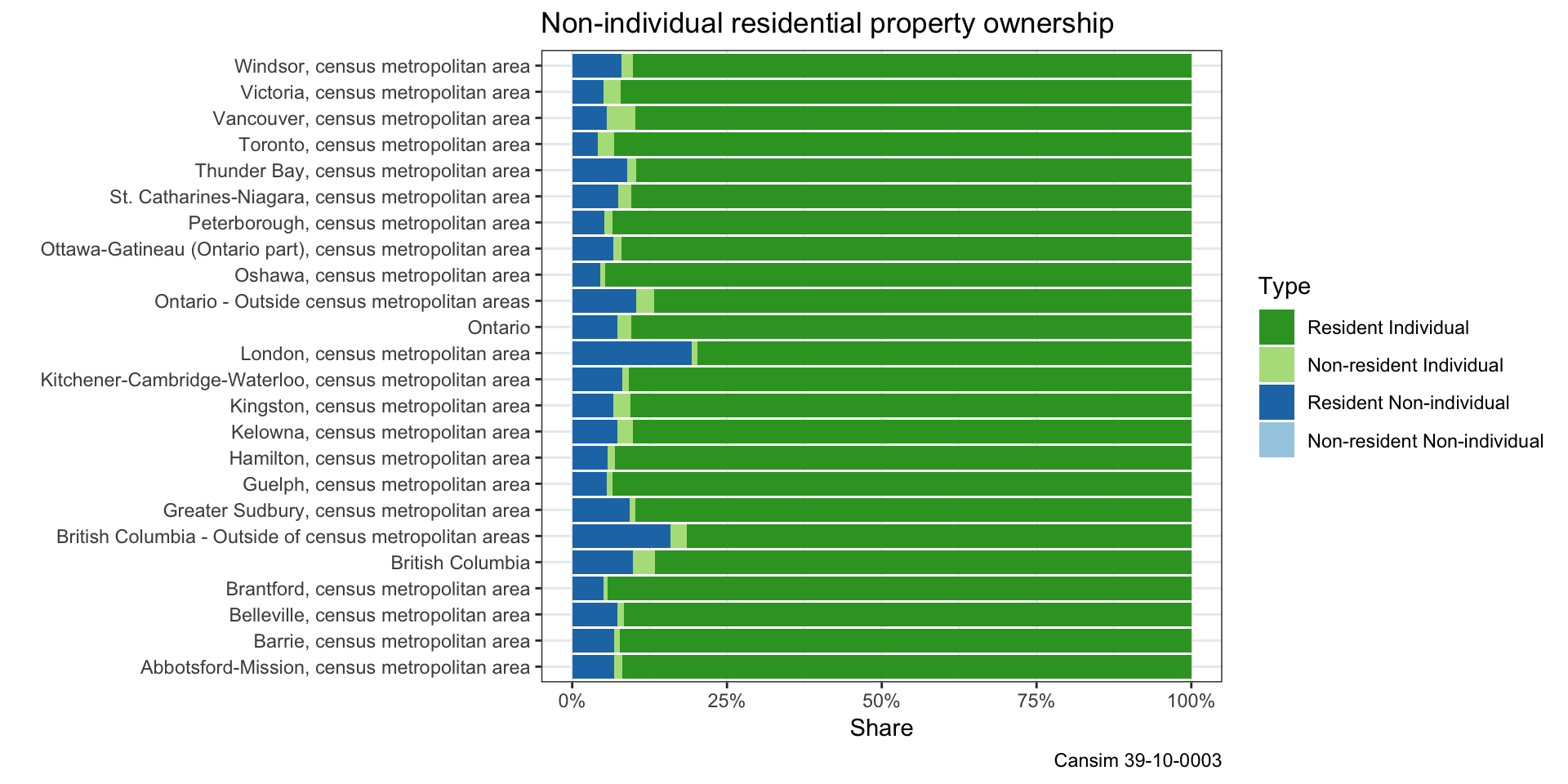

Via StatCan’s CHSP (CANSIM 39-10-0003) we now know that 5.61% of Metro Vancouver’s residential properties are owned by companies or trusts (or “non-individuals”), roughly in line with most other Canadian metropolitan areas in BC and ON as the following graph shows. Needless to say, the 100 most expensive properties on Vancouver’s west side are likely quite distinct from the rest.

Even after adding the non-resident owners to the non-individual owners, Vancouver still looks a lot like most other metro areas. In fact, the only metro area that really stands out is London, ON. Otherwise it’s the non-metropolitan portions of BC and ON that have the highest representation of company and trust ownership structures.

“In Metro Vancouver, homeownership costs amount to 87.8 per cent of a typical household’s income”

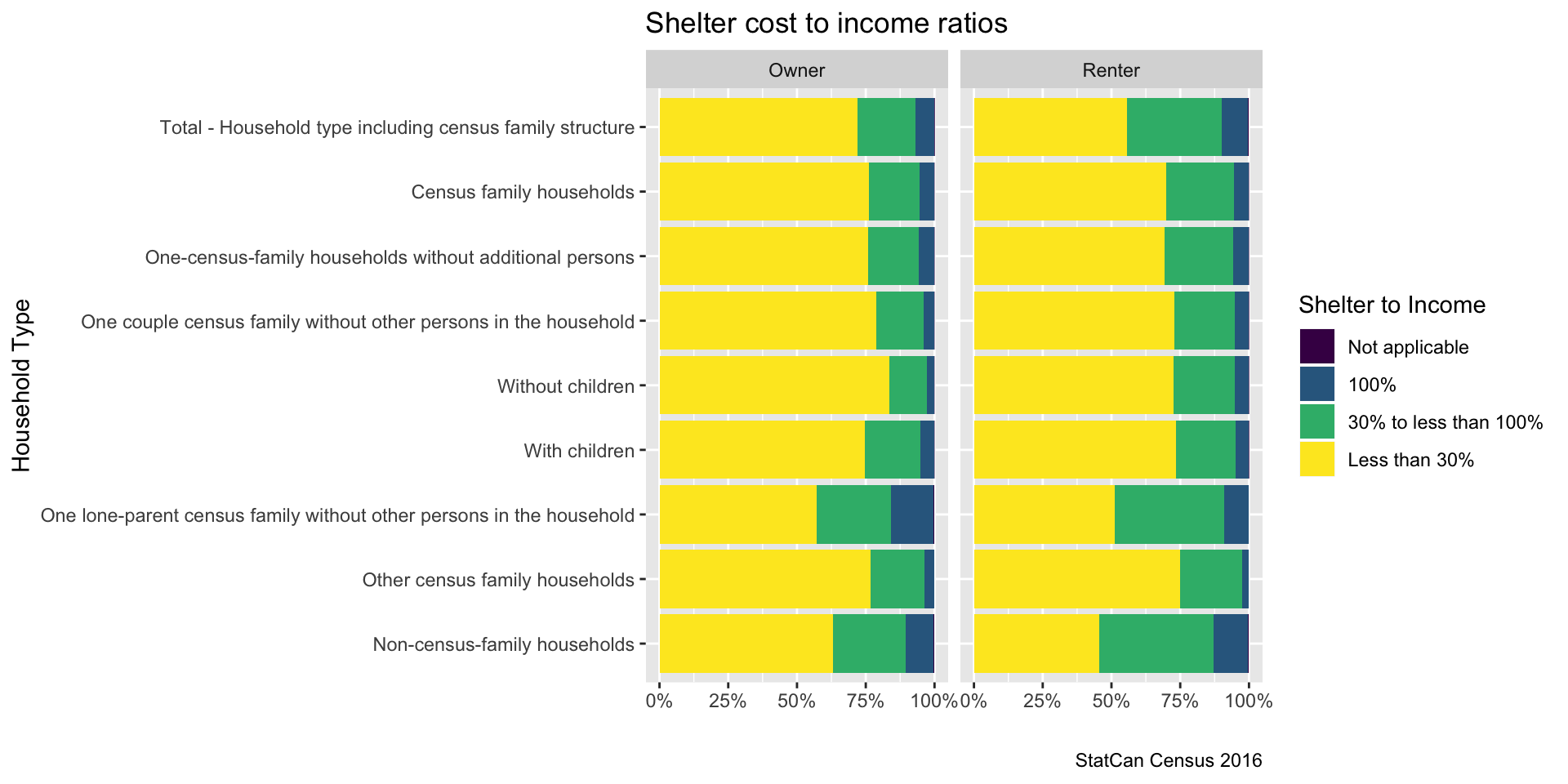

It does not. Most people spend far less, as the following graph on share of income spent by owners on shelter costs demonstrates.

The author appears to be conflating running shelter costs of owner households with the RBC affordability metric which compares the cost of financing the typical home for sale in the region to the typical household income. The latter metric may (imperfectly) reflect some of the difficulty now facing those wishing to jump from renting to owning, but has little bearing on how much typical households currently spend in either category.

“Vancouver has also become a major global hub for organized crime networks based in China.”

Here the author immediately pivots to the opioid crisis and the suspicious transactions identified in the recent money laundering report concerning lax oversight of casinos, attempting to link these to broader affordability issues and to globalization. To be clear, both the opioid epidemic and money laundering are serious issues in their own right. The fentanyl crisis has killed way too many British Columbians. As a recent report by Sandy Garossino notes, the criminal organizations associated with money laundering through BC Casinos have also claimed multiple lives. We should be outraged by the crisis and the crime ring, but it’s wrong, as Garossino adds, that this, “mainly bugs us because we figure it’s driving up the cost of housing in Vancouver.” The opioid epidemic demands more sustained attention than it’s likely to receive as a prop for tarring globalization. That’s not at all what it’s about. It requires a comprehensive re-think of our health care systems, pain management strategies, and criminalization of drug use, and the biggest villain in the story so far appears to be a major American pharmaceutical company. As for money laundering, further reporting on its role within the real estate sector has been promised by the Attorney General, but so far it’s not clear that shady practices - while certainly present - have had much to do with driving up real estate prices. As multiple commenters have noted, even if all the $100 million so far reported to have been laundered in our casinos over 10 years was re-invested in real estate, it would represent at most tiny fraction of total real estate transactions. Property transfer tax data shows that Metro Vancouver averaged $5.2bn worth of residential real estate transactions each month in 2017, dropping to $4.5bn during the first 5 months of 2018. There are real reasons to be outraged over the opioid epidemic and money laundering. But the link between these issues and affordability remains tenuous, and insisting upon the link in the absence of further reporting diminishes the importance of the documented damage they’ve already generated without pointing toward any good solutions for affordability, the opioid crisis, or tackling money laundering.

“Freeland could have been describing Vancouver: ‘Median wages have been stagnating, jobs are becoming more precarious, pensions uncertain, housing, child care and education harder to afford.’”

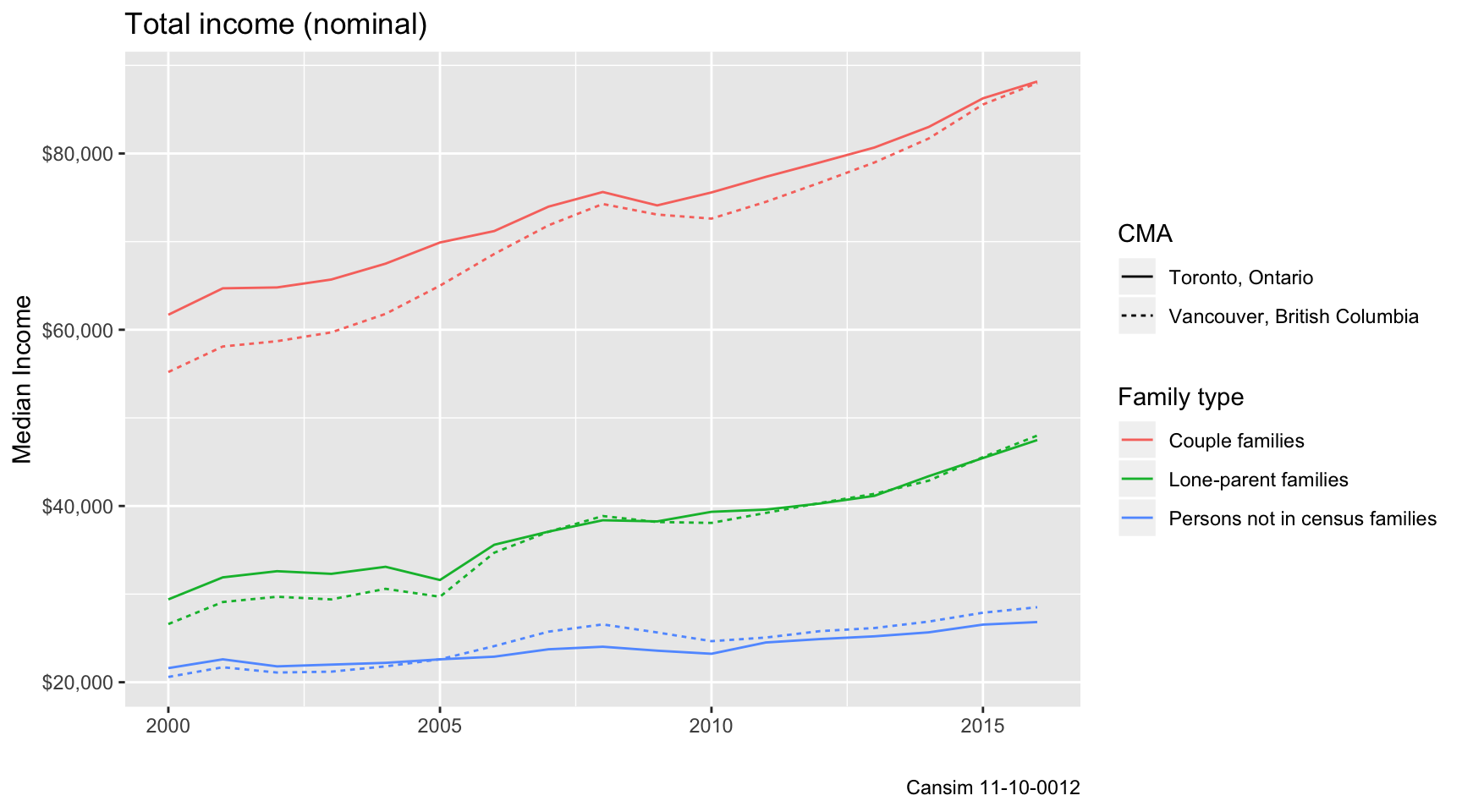

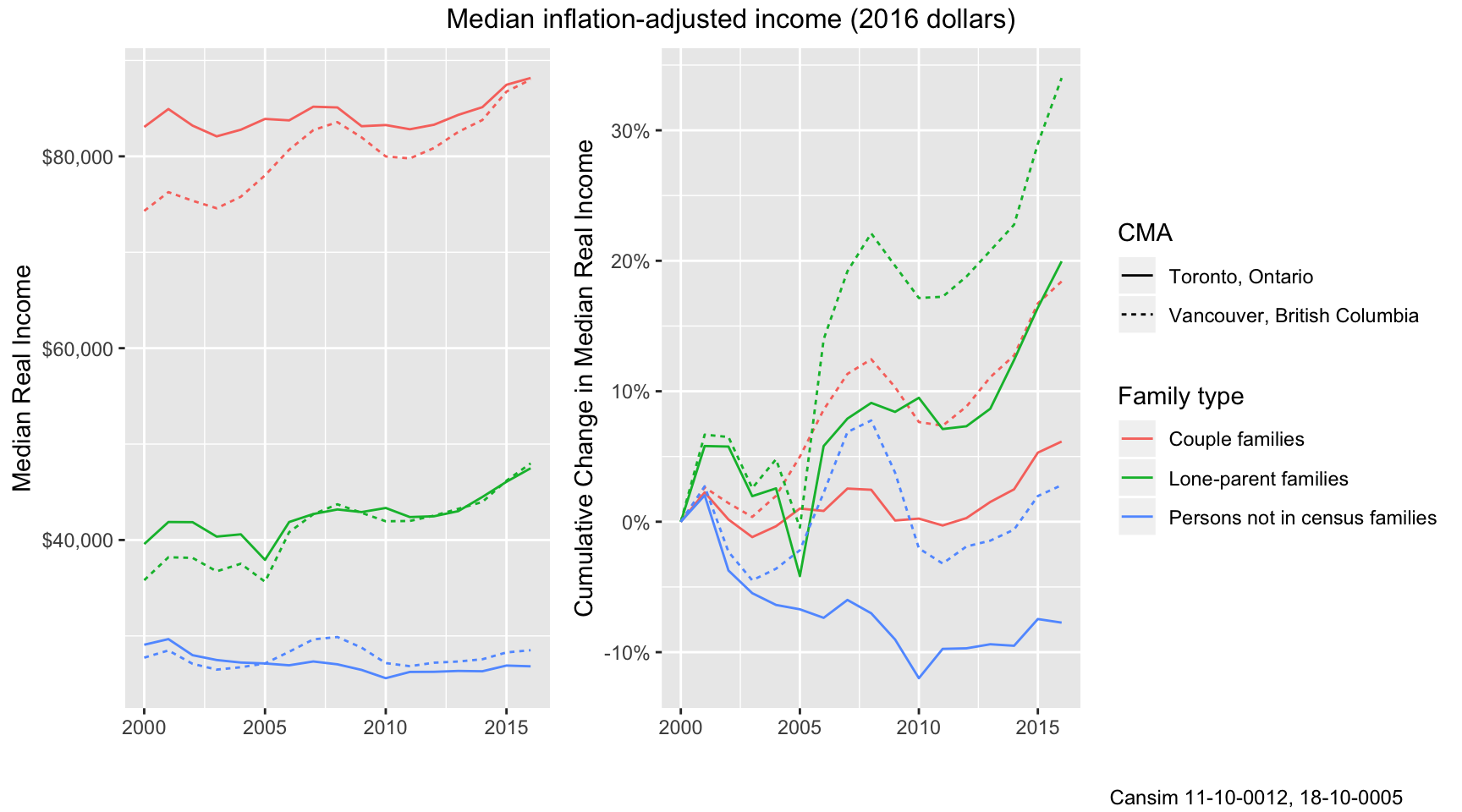

This is plain false. To its credit, back in February the NDP government moved to make childcare much more affordable for British Columbians. Why ignore this progress? Moreover, Vancouver has seen strong jobs and income growth. To gauge wage growth, we look at full-time employment income for couple families, lone parent families and unattached individuals and compare the trajectories to Metro Toronto.

We see that Vancouver CMA has overtaken Toronto for non-family individual income and lone-parent median income, and almost closed the gap on couple family income.

We see that Vancouver CMA has overtaken Toronto for non-family individual income and lone-parent median income, and almost closed the gap on couple family income.

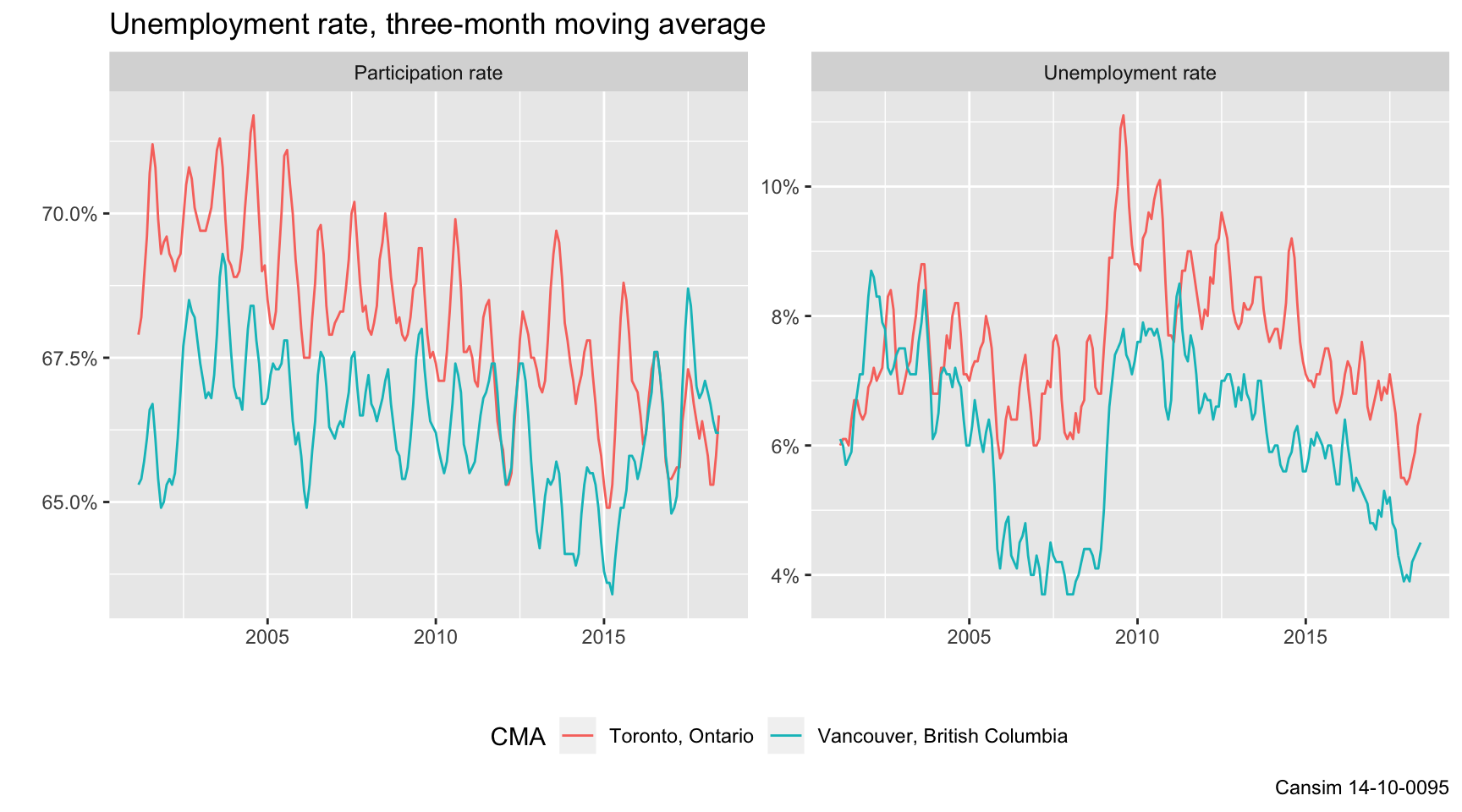

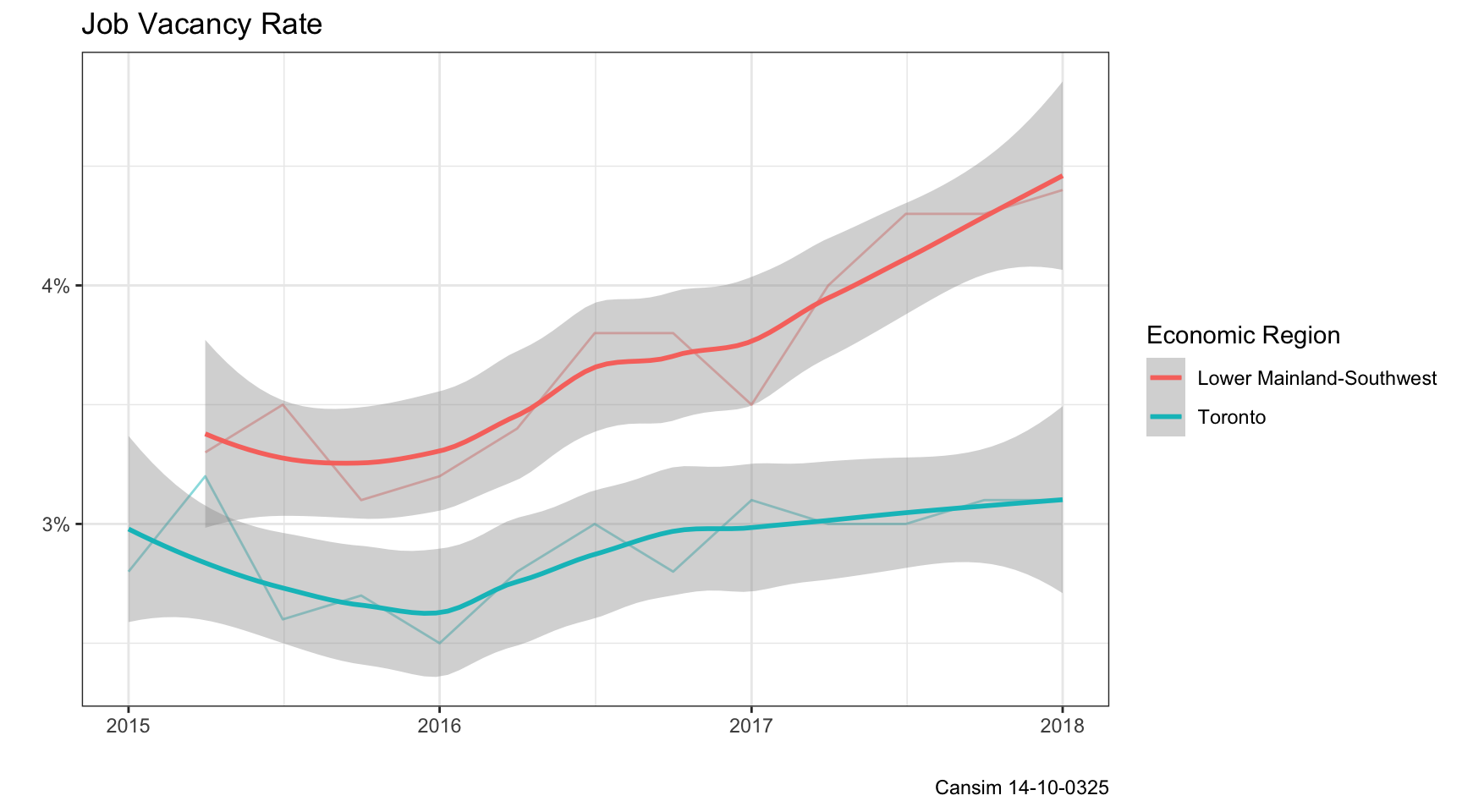

This shows how Vancouver’s labour force participation rate has increased with respect to Toronto while the unemployment rate decreased. Lastly we can look at the regional job vacancy rate for the respective economic regions to see how Vancouver’s job market is much stronger than the labour force is able to fill.

Afterword

In our hyper-polarized environment it is probably not enough to simply point out factual errors without further comment. So we take this opportunity to state that we strongly support stricter oversight and enforcement of money-laundering, as well as implementing measures to increase transparency in property ownership. We are also gravely concerned about Vancouver’s affordability problems. We’ve supported a number of housing policies recently put forward by local governments, including the empty homes tax, the school tax, and the boost to social housing investments, all aimed at fixing regulation and providing more housing to those most in need. It’s important to separate out what governments are doing right from where they might be failing. This is where swamp imagery fails us, blending everything together and dragging it all into the mud.

We think fixing our affordability problems is going to involve making tough choices and policy tradeoffs, and we should approach them with a clear sense of what’s at stake rather than mixed up facts, vague swamp-ish imagery and the sense it can all be blamed on the dark, corrupting forces of globalization. We’ve all seen where that last route can take us.

As usual, the underlying R Notebook for this post that includes all the code for the graphs and numbers in this post is available on GitHub. Feel free to download it to reproduce the analysis or adapt it for your own purposes. Hopefully this kind of transparent and reproducible analysis can help establish a shared base of facts. And reduce the amount of guessing needed to make sense of people’s numbers and statements.

Update (July 27, 2018)

Several people have pointed out via Twitter and comments that inflation-adjusted income growth might be a better metric to use. And that’s a good point. In the context of housing we often have nominal housing prices in mind, so nominal income can be a good metric in this context. But inflation-adjusted incomes add another important perspective.

Here we used Canada-wide inflation estimates, Vancouver’s income growth looks even stronger when normalizing by CMA-specific CPI. (Digging into the reasons for this would probably make another interesting blog post.) The two graphs show the inflation-adjusted incomes, as well as change in adjusted incomes indexed to 2000. We can clearly see the growth in all categories, both in absolute terms, as well as in relative terms compared to Toronto. Despite this, the notion of “stagnant incomes” in Vancouver is quite pervasive in news stories.

PS

This was written jointly with Nathan Lauster and cross-posted on his blog.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{fact-checking-vancouver-s-swamp-drainers.2018,

author = {Lauster, Nathan and {von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Fact-Checking {Vancouver’s} {Swamp} {Drainers}},

date = {2018-07-22},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2018-07-22-fact-checking-vancouver-s-swamp-drainers/},

langid = {en}

}