Vancouver has low property taxes and high income taxes. Seattle is the opposite. What would it look like if British Columbia was more like Washington State? If we got rid of personal provincial income tax and recovered the revenue by raising the provincial portion of the residential property tax, a.k.a. the “school tax”.

The tax policy of British Columbia, when compared to Washington, is sending the message that it’s a great place to come and invest in property with it’s low property tax rate, but not such a great place to live and work with it’s higher income tax rate. There have been a number of initiatives to try and change this, from the BC Housing Affordability Fund that aims to raise property taxes for those that don’t work here, to the Extra School Tax on properties over $3M that raises property taxes on expensive properties and follows arguments for a progressive property tax, to the “speculation tax” that is being discussed and the details are getting fleshed out right now.

But there has been little public discussion about the simplest solution that is virtually impossible to avoid: Get rid of the provincial income tax and shift the entire tax load to property taxes. That would discourage using property as investment, soften price volatility and give people that work and pay taxes in BC an edge. This tax setup may seem a little radical to some in Vancouver, but it’s totally normal to people in Seattle.

The numbers

Let’s look at the numbers. The current BC budget for 2018∕2019 estimates a personal income tax revenue of $9.53 billion. The total 2018 property tax assessment for residential (Class 1) properties in BC was $1,445.51 billion for the 2018 tax year. So to offset the foregone income tax we would need an additional flat property tax rate of 0.66%. Or possibly choose something more complex like a progressive property tax. And we might want to exclude purpose-built rental buildings from this, that would certainly help get more of those built. (Although property taxes on rental buildings are tax-deductible, so the net effect on these is softer.) For now, let’s go with the flat tax.

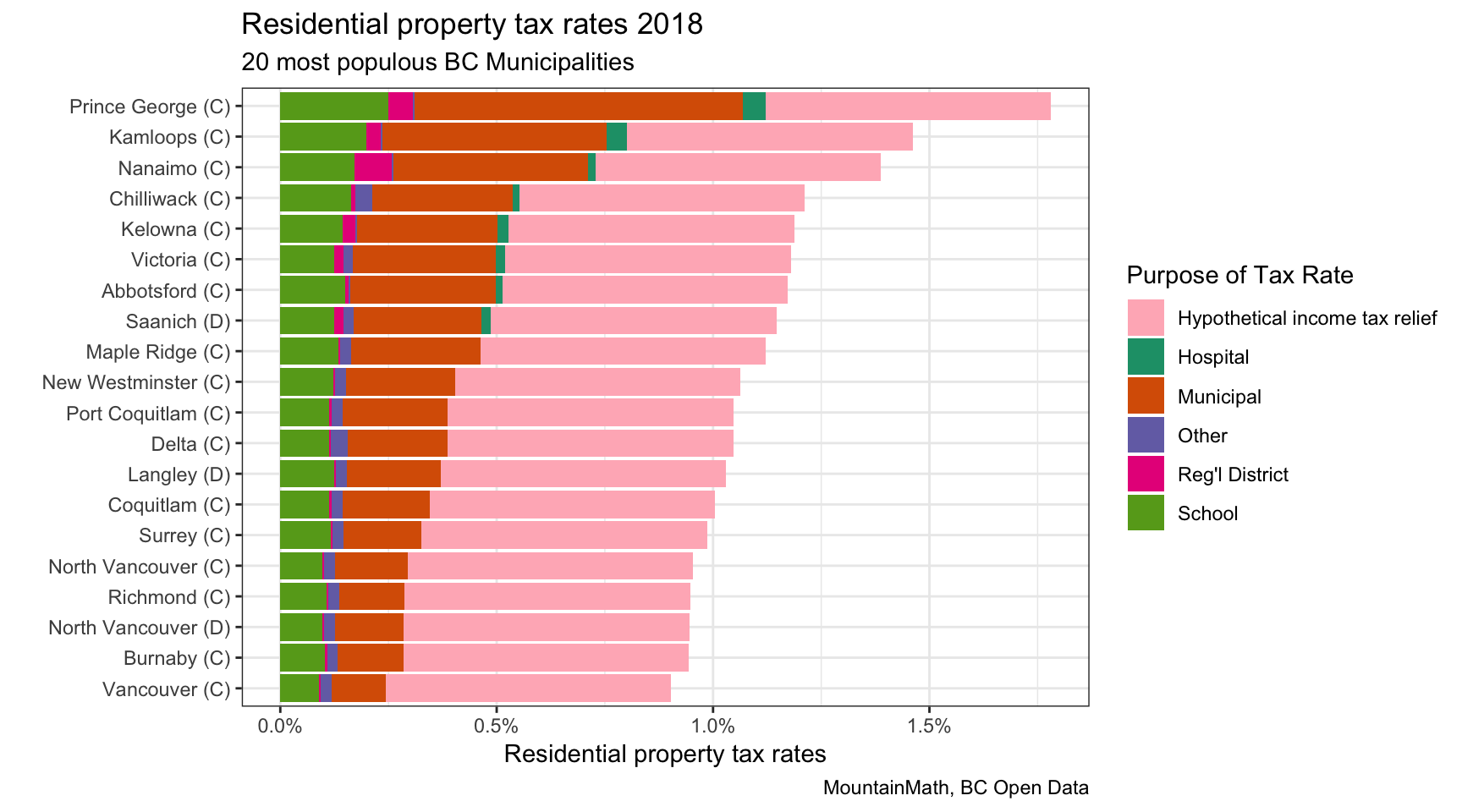

The property tax rate in King County is 1.02%. How would that compare with British Columbia’s rates? Let’s add in the “hypothetical income tax relief” portion of the property tax.

This shows that if we followed Washington State’s example and nixed our provincial income tax and recovered the lost revenue from property taxes, most of the larger cities would end up with a tax rate similar to Seattle’s.

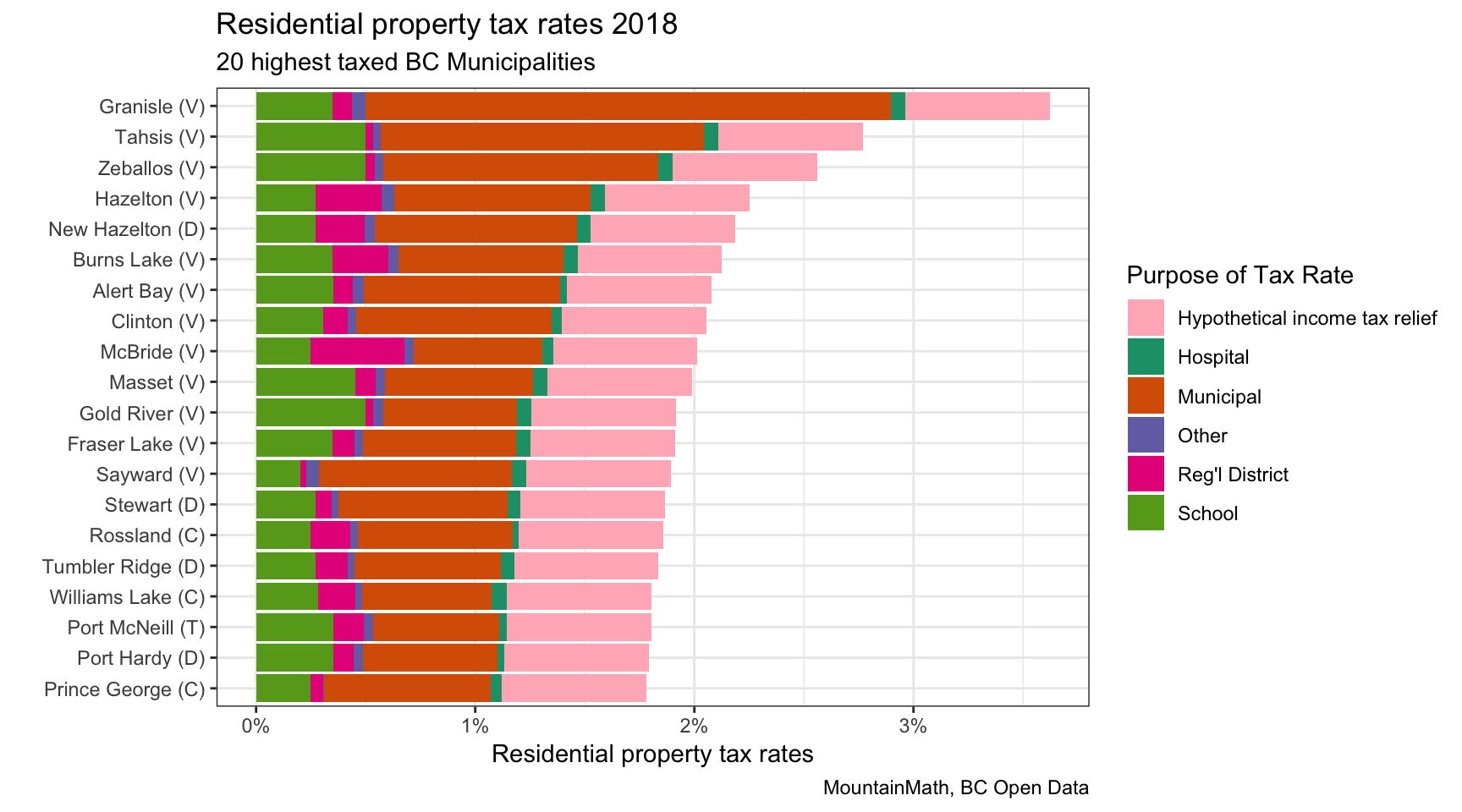

But how about the smaller cities? Let’s take a look at the highest taxed municipalities.

We see that the spread is not that large, although a few of the very small municipalities have substantially higher tax rates. So substituting the income tax revenue through increased “school tax” brings essentially all of British Columbia into the range of King County’s property taxes.

The effect on homeowners

Let’s look at what this translates into on the ground. For Metro Vancouver we had an average owner-occupied home value of $1,005,920 in 2016, and average annual shelter costs, including mortgage payments, property taxes and regular home maintenance, but also utilities, of $19,464. (Averages are better suited than medians for this kind of calculations, but that choice does not make much of a difference for the results). This shows that the average shelter cost would go up by $6,635, an increase of the average running shelter cost by 34.1%.

That looks like a substantial increase, but we need to remember that this is offset by getting rid of the provincial income tax. The average effective provincial tax rate was 5.61%, so people will have on average 5.61% more after-tax income to take home. Homeowners in Metro Vancouver had an average household income of $115,760, resulting in a lowballed average increase in after-tax income of $6,490.43. That number is lowballing it since Metro Vancouver homeowners tend to have higher incomes than the average British Columbia household, so they will have a higher effective provincial tax rate and thus higher savings.

Winners and losers

Whenever there is a change in the tax system there will be winners and losers. The hypothetical tax change is revenue neutral, so on average everyone comes out even. Except homeowners that don’t live or don’t pay taxes in BC, those will pay extra. So the BC taxpaying resident will come out on top. On average, and that is also supported by our rough analysis using census data above.

Some will pay extra, in particular homeowners in high-value homes with low income, including some seniors. Others would end up on top, for example high earners in lower value housing or renting.

It would probably be worthwhile to dig down further and understand who the winners and losers would be after such a policy change.

Impact on property values

But higher property taxes depress property values. But by how much? On the other hand, increasing after-tax income puts upward pressure on home prices. Estimating and comparing these effects is tricky business. But we can give a simplified heuristic argument to get a rough idea of the possible effects.

We can estimate the effect of raising property taxes on home values by computing the present value of the additional future tax payments. Using a discount rate of 3.5% we get a present value of 12.1% of the home value assuming a 30 year revenue stream, or if we assume perpetual payments we get 18.8% of the home value. That gives us a range by which this could lower home values.

For people working and paying taxes in BC this would be offset by a the ability to spend more on housing due to lower income taxes. Estimating the effect of that is a bit harder as it requires a lot more assumptions. Perhaps a simple way to estimate it is to compare (a portion of) the present value of the tax savings and compare that to home values. If we dedicate the entire tax savings to housing we an upward pressure on home prices by 11.9%, if we only dedicate a third of the tax savings to housing and spend the remainder on other things we get an home price increase of 3.96%. So rising after-tax income would somewhat offset the downward pressure from property taxes.

On balance the tax shift will likely exert a little downward pressure on home prices. Which in turn would require rising the hypothetical property tax relief rate a bit. But simple math shows things would stabilize pretty quickly.

Again that’s an over-simplified view on the issue, and things are never that simple. Especially when it comes to Vancouver real estate. I will leave it to the economists to refine this appropriately.

As always, the code underlying this post is available on GitHub, feel free to grab it and adapt four your own purposes.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{taxing-property-instead-of-income-in-b-c.2018,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Taxing Property Instead of Income in {B.C.}},

date = {2018-08-10},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2018-08-10-taxing-property-instead-of-income-in-b-c/},

langid = {en}

}