City of Vancouver council rejected the development application for 21 purpose-built rental townhouses in Vancouver’s exclusive enclave of Shaughnessy last week, and the owner is now proceeding with building a mansion on that lot instead.

Councillors gave a variety of reasons for the rejection. Some were voicing concerns of about the compatibility of hospice use with the 3 1/2 storey townhouse development next door, which seems far fetched as a quick look at St John’s hospice at UBC (the low building on the right in the picture here) shows. There the hospice wanted to locate directly next to a 19 storey condo tower, and condo owners fought tooth and nail to stop the hospice from getting built. The difference there is that the condo tower was their first and it was the condo tower that was arguing that these are incompatible uses, while in Shaughnessy the hospice was first and was arguing that the townhouses are incompatible use. In both cases, some design changes were made to the respective new developments to enhance privacy of the respective other side. Bottom line, hospice and residential developments can happily co-exist, those that claim otherwise are plain NIMBYing.

Councillors gave a variety of reasons for the rejection. Some were voicing concerns of about the compatibility of hospice use with the 3 1/2 storey townhouse development next door, which seems far fetched as a quick look at St John’s hospice at UBC (the low building on the right in the picture here) shows. There the hospice wanted to locate directly next to a 19 storey condo tower, and condo owners fought tooth and nail to stop the hospice from getting built. The difference there is that the condo tower was their first and it was the condo tower that was arguing that these are incompatible uses, while in Shaughnessy the hospice was first and was arguing that the townhouses are incompatible use. In both cases, some design changes were made to the respective new developments to enhance privacy of the respective other side. Bottom line, hospice and residential developments can happily co-exist, those that claim otherwise are plain NIMBYing.

Another reason cited was construction noise that would impact the hospice. The city negotiated a good neighbour agreement that would pause construction during certain times of day to lessen the impact. No property, including the hospice, can reasonably expect a development bubble around their property. A good neighbour agreement is pretty much the best one can hope for. Now the hospice is getting a 12,000sf mansion development next door without a good neighbour agreement. To top things off, the hospice made it known during the public hearing that they are interested in buying the lot and developing a senior centre there. Apart from the obvious conflict of interest wrt stopping the townhouses, this also calls the hospice’s concerns about development related disruptions into question.

One green councillor argued they voted against the project because there wasn’t enough consultation, while the other two Green councillors said they voted against it because there was too much parking, parking that was added in response to community feedback during consultation.

Probably the biggest concern that was that “the rents are just going to be too high for people who rent to afford”. Which is a point that comes up a lot with new developments and deserves some unpacking.

20 fewer families in Vancouver

The bottom line of the council vote is that 20 fewer families will be living in Vancouver, or maybe 19 or 18 as the owner indicated he is planning to occupy the mansion with his extended family. Given Vancouver’s vanishing rental vacancy rate, it’s safe to assume that all these units will be occupied.

Who are these 20 families? We don’t know, we don’t know their faces. Which is what makes it so easy for council to vote them down. But it’s not the 20 families that can afford the rents in these Townhouses that will get pushed out of Vancouver as a result, these families will simply bid up rents somewhere else in the city. It’s lower income families further down the income distribution that will get pushed out of Vancouver as a result of council’s decision. This is a process that has been going on for quite a while now, with the City of Vancouver bleeding low income households and gaining high income households faster than the rest of the region.

It bears repeating that it’s the low income people that are most impacted by the decision to deny those townhouses to get built, a general phenomenon recently described in detail using panel data in the US by Evan Mast and umpacked by Stephen Quinn a couple of days ago.

It’s probably worth to spend a bit of time to contextualize this for the Vancouver setting.

Affordability

To start off, let’s look at the claim that the townhouses would be unaffordable. As Jill Atkey observed, a family moving into a 3 bedroom unit would need about $140k in pre-tax income to meet the standard affordability definition. Some people were quick to point to median household incomes as a proof that families won’t be able to afford them. But incomes, just like housing costs or rents, are a distribution. And needs of households vary.

And in situations like this it’s important to remember the fine print in Canada’s core housing need metric, in particular the part that looks at suitability of the unit. It essentially says that when it comes to 3 bedroom units, we should be looking toward families with children and ask if it’s affordable to them, the question if the 3 bedroom unit is affordable to a one-person household is not relevant. In fact, an overhoused household that spends more than 30% of their income on housing but could afford a right-sized unit in their neighbourhood is not considered to be in core housing need. One can argue about the details of the metric, but probably everyone can agree that the target population for a 3 bedroom townhouse is a family with children and not a 1 person household.

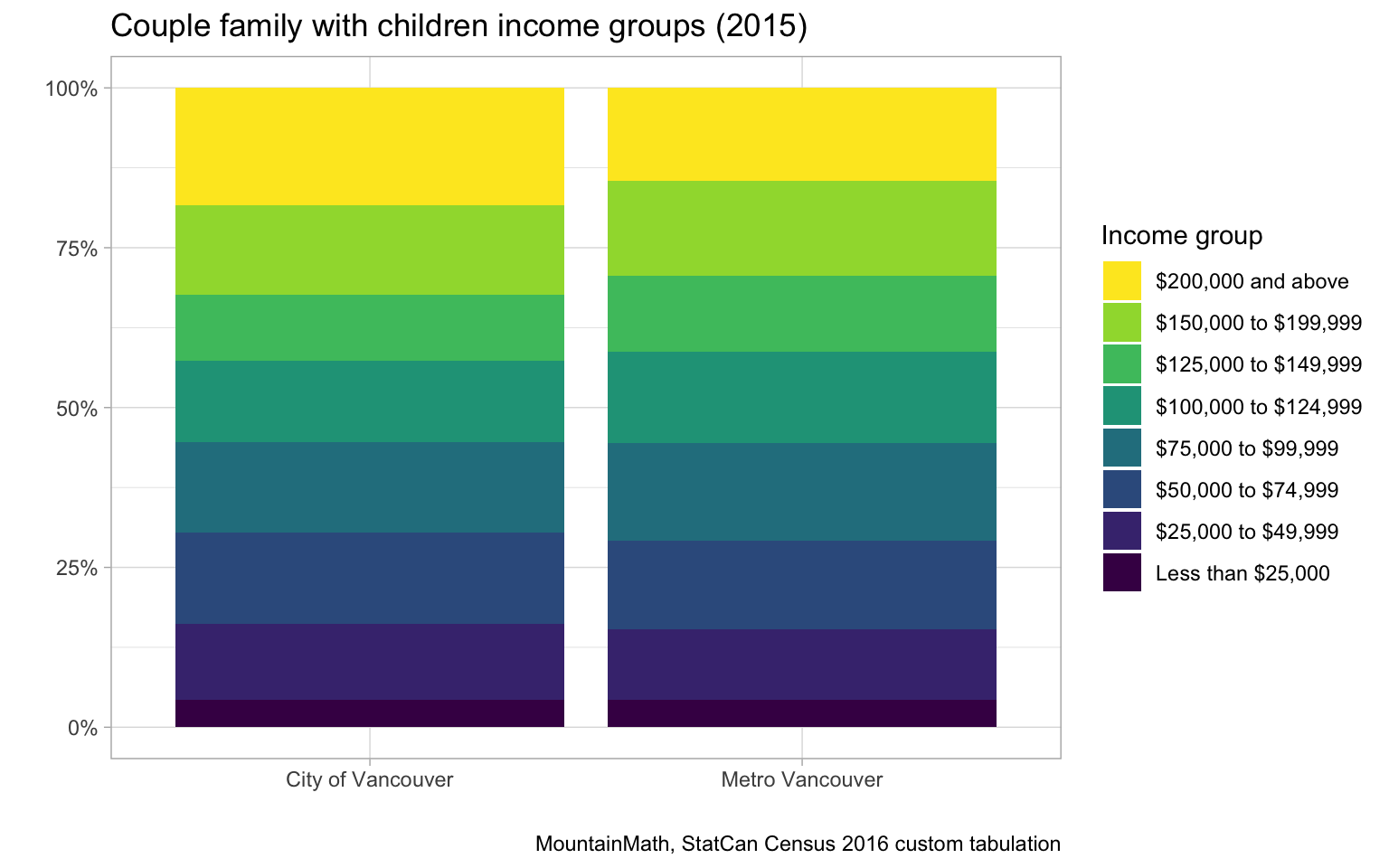

So let’s look at incomes of families with children at home. In 2015 the median income was $111,636 in the City of Vancouver and $112,167 in the Metro region. So the median family with children won’t be able to afford these townhouses, but what portion of families will? We don’t have data on that exact question, but we do have a crosstab that allows us to check what portion had an income of $150k or more in 2015.

In the City of Vancouver 32.3% of all families with children at home had an income of at least $150k in 2015, for Metro Vancouver the share is 29.4%. So these townhouses are affordable to almost one third of families with children at home.

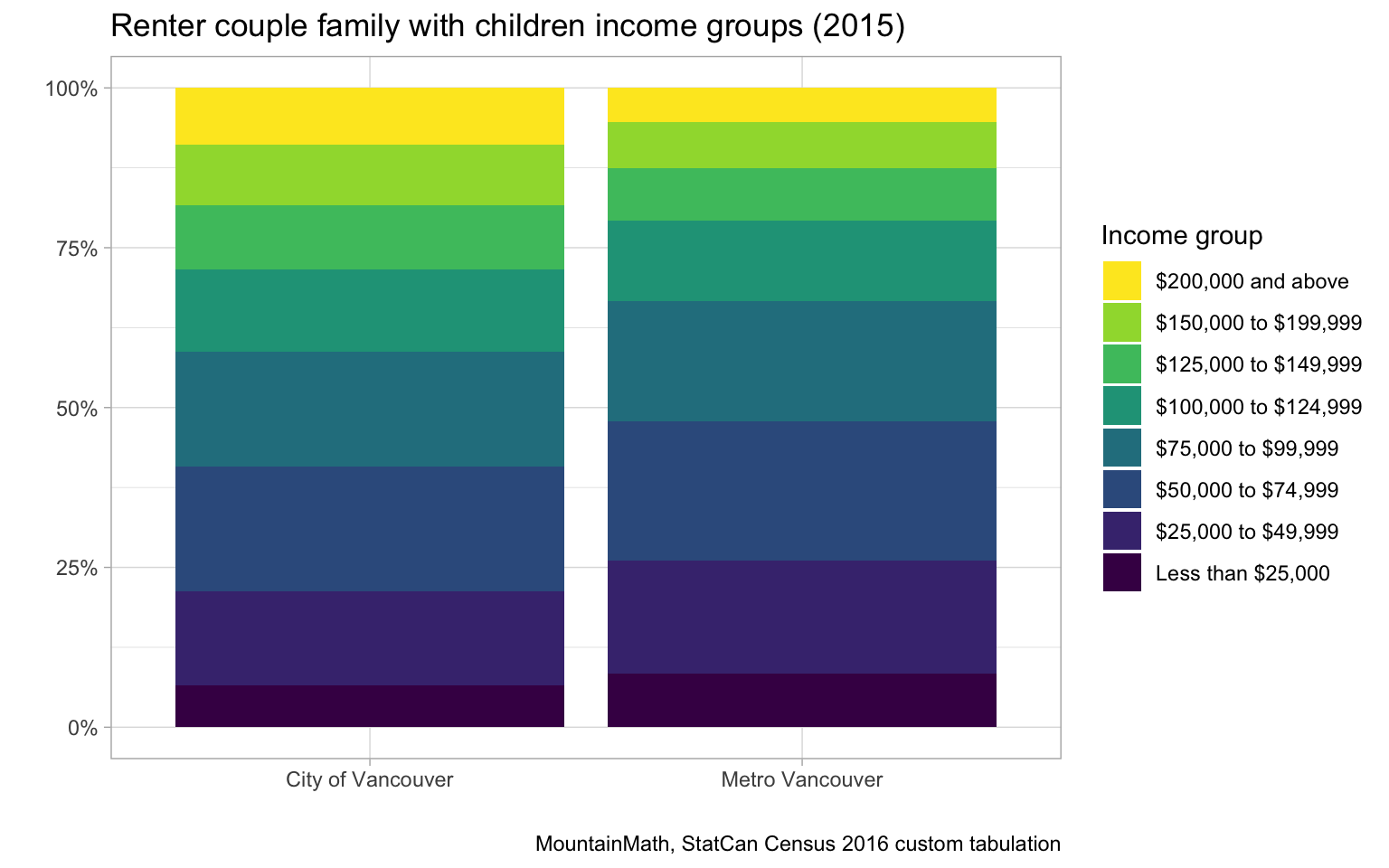

Renter households tend to have lower incomes, as a second metric we can just look at renter households in market rentals.

The shares of families with children at home making at least $150k in 2015 are 18.3% and 12.6% for the city and the Metro area, respectively. That’s a significantly lower portion, but still a sizeable contingent of families, even at the $150k level instead of the more stringent $140k affordability cutoff. And that’s not accounting for these townhouses being centrally located with excellent access to transit which translates into transportation (and time) cost savings. And that family incomes have risen substantially since and will have increased, and with them the share to whom the townhouses would be affordable.

The simple reality that income is a distribution, and that there is a sizable portion of families that can afford to rent these townhouses, should not need pointing out. And of course we knew that since the townhouses would have gotten rented out. When someon is arguing that these won’t be affordable, they essentially say that they won’t be affordable to the population they care about. But that’s a very short-sighted argument, housing units are part of a complex housing system.

System effects

So lets assume council really did not care about families with children in the top 30% (or 15%) of the income distribution. As explained above, those families aren’t the ones that will get displaced from Vancouver as a result, the perverse effect of council’s decision is that it’s lower income families that get pushed out.

We need to think of housing as a system. Only allowing housing for you favourite clientele, or only allowing your favourite type of housing, is not going to solve our housing crisis. We do need more housing of all types, non-market housing as well as market housing. We simply don’t have the capacity to build enough non-market housing for everyone, we also need to build more market housing to lower the entry rents to market housing. The problem needs to be attacked from both sides. We understand well how vacancy rates relate to rent increases, and cities like Seattle show that a massive increase in building can indeed lead to lower rents last year, with now rents rising much slower than the national average and landlords giving out perks to attract renters before adjusting for the increase in quality that the influx of new units brings.

Upshot

Not building those townhouses does not reduce demand, it merely reduces the number of people than can live here, and increases competition for the remaining units. Of course 21 townhouses by themselves don’t make much of a difference in placating our latent demand for housing. And given how long it took council to debate this one project I am having my doubts that a reasonable number of smaller rental projects can get approved if things continue at this pace. Unless council is going for larger projects like some of the MIRHPP that are in the pipeline (and haven’t dropped out yet). Personally, I prefer the shorter “missing middle” type housing, including townhouses and lowrise, but I will take any rental housing Vancouver can get. It’s badly needed, and the MIRHPP projects include 20% of below market rental units as an added incentive. Hopefully that will soften some of the affordability concerns from those people that can’t wrap their head around the system effects. We shall see how council will handle the MIRHPP projects when they are coming up for a vote.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{shaughnessy-townhomes.2019,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Shaughnessy {Townhomes}},

date = {2019-07-07},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-07-07-shaughnessy-townhomes/},

langid = {en}

}