Metro Vancouver’s population is growing. For planning purposes we want to understand how our population will be growing. For that we need projections.

Here we need to carefully distinguish two related but distinct types of population projections.

- projections of population demand, and

- projections of population growth.

Projecting demand, or even just estimating current population demand, is complex. Demand is a function of a variety of factors, most importantly jobs, and amenities, as well as home prices and rents (in relation to incomes and wealth). Jobs and amenities, relative to other areas, determine the attractiveness of a region to in-migration (and the dissuasion to out-migration). Natural growth (birth minus deaths) is only a small factor in Metro Vancouver’s growth.

This attractiveness of a region sets an abstract upper limit for population demand. Actual population growth up to the abstract upper limit depends on the amount of available housing (relating to population demand via households). This is where we have to remember that demand is a function of price, and the abstract upper limit on population demand is built on the assumption that people can find housing at an acceptable price. In reality, the population demand is curbed through market prices for market housing, and waitlists for non-market housing. This is how population demand and population growth meet.

For planning purposes, defining demand through current market prices is tautological and not very useful. After all, population projections are often used to limit the amount of permitted housing. Which leaves us with the question: What is the cost of housing we should estimate population demand at?

For market housing, a good, albeit somewhat abstract, answer is Glaeser’s Minimum Profitable Production Cost (MPPC), that is the cost to add housing to a given market, which depends on construction cost (which will rise with density and could use some refinement), augmented by municipal service charges and possibly other charges, for example charges aimed to maintain livability, the cost of land (usually taken to be 20% of construction cost and service charges), and a developer profit. While the MPPC in Vancouver is high, the price of market housing is even higher than that. In the media this is often described as elevated land values. Land values of a housing unit is the residual value that buyers are willing to pay above what it costs to construct the unit (including development charges). That differential is negotiated through supply and demand of market housing.

Demand for non-market housing is, by definition, not negotiated through price. The distribution of non-market housing is done via eligibility criteria and waitlists. Demand can be approximated by the length of the waitlist, although that will generally be a substantial under-estimate in real life situations where wait list tend to be so long that many eligible households don’t even bother applying.

A look at population demand in Vancouver and Calgary

It is safe to say that Vancouver’s amenity value is comparatively high, but it is hard to quantify that. Quantifying the job market is much easier. For comparison we choose Calgary, also a city with high amenity value, although probably not quite as high even though it often features high in livability surveys. However, at this time Calgary facing a very different jobs market from Vancouver.

Calgary has a healthy existing housing supply to accommodate mild population growth with a primary market rental vacancy rate of 3.9% and a private condo rental vacancy rate of 2.7%. At the same time Calgary is continuing to add new housing units at a good pace with apartment building starts for the first six months of 2019 only 2.5% below the corresponding 10 year average and completions and apartment units under construction up by 15.9% and 14.0%, respectively.

Economic indicators in Calgary are slowly improving, but current economic conditions show a relatively high unemployment rate of 7.0%, above the Canadian average of 5.5%. At the same time, Calgary has a job vacancy rate of 2.5%, below the Canadian average of 3.1%. That means that unless economic conditions change we expect that on balance people to move away from Calgary over the long term.

This means that Calgary’s housing market likely has a bit of a buffer at this point so that population demand and population growth are roughly the same right now, which simplifies things.

In Vancouver on the other hand, population demand and population growth are quite different. Vancouver’s unemployment rate sits at 4.0% while the job vacancy rate of the economic region is 4.9%. The current population can’t fill the existing jobs, and with current primary and secondary market rental vacancy rates at an anemic 1.0% and 0.3%, respectively, there is no way for people wanting to fill those jobs to move into the region. Current population demand is significantly higher than population growth. Dwelling growth becomes a hard cap on population growth.

The silver lining in this desperate situation is that apartment building starts in the first half of 2019 is a whopping 102.7% above the corresponding 10 year average and completions and apartment units under construction are up by 41.9% and 78.1%, respectively. One should note however that at current rates at fairly high completions it would take about 15 months to complete the number of dwelling units needed to make room for the 26,537 workers (at a healthy average rate of 1.3 workers per dwelling unit, and completely ignoring the need for moving vacancies) to bring Vancouver’s job vacancy rate down to the Canadian average. And that’s not accounting for jobs created through continued economic growth or knock-on effects of the economic activity associated with adding these workers and filling the jobs. Thus it will take a while to clear the backlog of undersupply, let alone catch up with latent demand due to delayed household formation, overcrowded households and bring the rental vacancy rate up to healthy levels.

In clearing the backlog, Vancouver’s prices and rents will have to adjust to meet this demand, with recent demand side measures like the City of Vancouver Empty Homes Tax and the vacancy tax component of the provincial Speculation and Vacancy Tax helping ensure that properties get occupied and thus aiding the process of price and rent adjustments.

This means that at least for the shorter term future Vancouver will have to arrange itself with a significant gap between population demand and population growth, and the associated market selection mechanism sorting out who gets to come/stay and who gets pushed or shut out of market housing, and our non-market mechanisms selecting how gets to occupy non-market housing units.

Planning for growth

In our highly regulated building environment, population projections (and dwelling projections) are turned into a high-stakes game. In Vancouver, we rely on the Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy (RGS) to set population and dwelling growth targets, and distribute the growth across the municipalities within the region. Those targets are then used as a guideline for how much new construction to permit.

At the metro level, there are three possible outcomes:

- The RGS overestimates population demand and we permit more housing than needed.

- The RGS correctly estimates population demand and we permit exactly as much housing as needed.

- The RGS underestimates population demand and/or we permit too little housing.

In the first case, developers will simply stop building excess housing since providing housing in excess of demand becomes unprofitable fast. The second case essentially never happens, projections are always wrong. The third case is the case of a housing shortage, which leads to people getting shut out of the region, price growth for ownership and rental housing, and a dampening of the economy due to labour shortages.

The costs for under-estimating growth are high (while the cost to over-estimate growth is low). Time to take a more careful look at the RGS.

Benchmarking the RGS

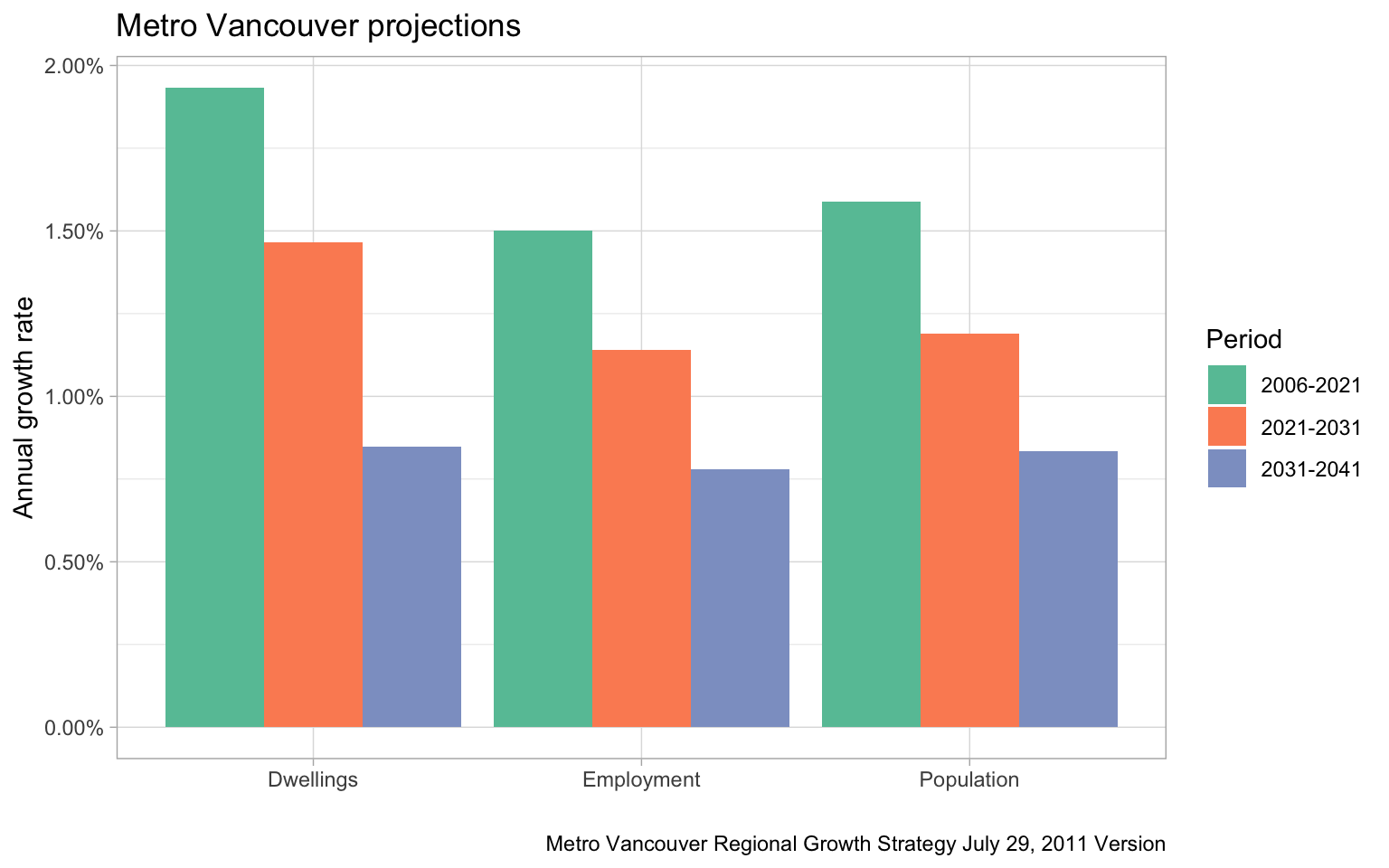

To illustrate this we can look at the (now dated) population projections by the Metro Vancouver Regional District, (now just called Metro Vancouver) from 2010.

The projections call for a slowing of the growth in the region over the years. In the beginning, dwelling growth exceeds population growth to account for shrinking household size, but curiously the model has almost identical dwelling and population growth rates for 2031 to 2041. Unfortunately there is no further explanation how the model was derived, but this seems to assume that household size stabilizes by the 2031-2041 period and all latent demand has been dealt with. Employment is projected to rise at a slightly slower rate than population, probably reflecting the shrinking portion of the population in the work force as the share of seniors continues to increase and the entry time in the labour market continues to get delayed due to increasing levels of education.

Long term projections are hard, so let’s focus on the short term until 2021. And interpolate values for the 5 year intervals given by census years that allow us to check how the projections held up. For simplicity, we will assume the growth rates to be constant within each interval, the exact way we interpolate does not make much of the difference for what follows. Projections are always bound to be different from actual numbers anyway, what this post focuses on is the relative difference between the three metrics.

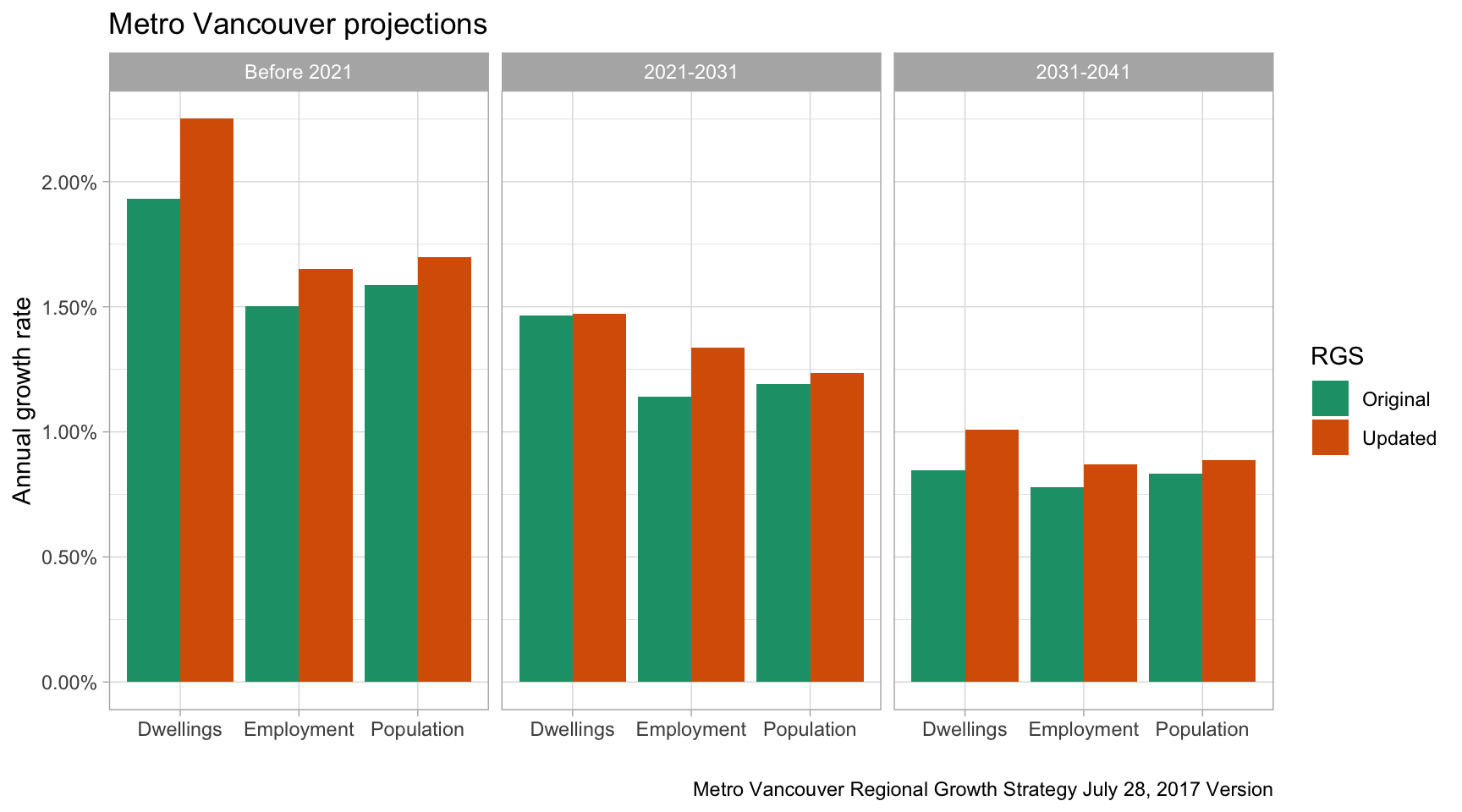

The Regional Growth Strategy was updated in 2017, and it is a worthwhile exercise to check how the updated projections compare.

We see that the updated projections sport slightly higher growth rates, and also remove the assumption of a stop to shrinking household size for the 2031-2041 period.

How to measure population, dwellings and employment

To understand population demand we need to at least measure population, dwellings and jobs/employment.

The question how to measure these metrics is surprisingly less straight-forward than it seems. Ideally we want high-frequency data so we can closely monitor how our region is changing. Annual data is probably good enough for that. StatCan has a number of annual tables at the CMA level that can inform on employment and population growth, although the employment tables are based on place of residence and not place of work. Which makes a difference when there are changes in net commute patterns for Metro Vancouver. The census also counts population and employment, although one needs to adjust for the census undercounts.

StatCan does not have good tables on the number of dwelling units, although CHSP data is starting to use administrative data to count residential properties. Folding in unit counts for each property gets us closer to dwelling units, but this still fails to account for some informal dwellings, like non-authorized secondary suites. BC Stats has annual estimates of dwelling units that can also be used. The census has (private) dwelling counts, but they generally under-count as the census inevitably misses dwelling units, as we also need to account for collective dwellings.

Finer geography data, so data for municipalities within Metro Vancouver, are harder to get from the annual StatCan tables, although BC Stats has population estimates (and projections) at the municipal level, and custom tabulations are available at least for the larger municipalities. Census data is available on municipal and sub-municipal geographies, but the numbers still need to be adjusted for undercounts and net commute flows.

Sorting out these details takes more effort than what we are willing to spent on this post. We will focus on growth rates and differences over given time periods, what’s most important is to choose consistent metrics for this. Differences stemming from the particular choice of metric tend to divide out this way, and we will ignore related issues for this post as they are smaller than the effects we are interested in.

The RGS is unfortunately a bit vague on how exactly the base estimates were derived, stating that dwelling counts (just private or private and collective?) are based on the census, and population and employment (not jobs) estimates are derived from the census and were adjusted for census undercounts (probably via a custom-tabulation at the sub-metro level?).

Comparing metrics

Population counts at the metropolitan level are easily available from StatCan table 17-10-0135 that is already adjusted for census undercounts, but is anchored on July 1st, almost two months after the census. For Metro Vancouver, that came out at 2,188,743, quite close to the 2,195,000 from the Regional Growth Strategy.

Next up is the number of dwellings, those should be straight-up census numbers, but the RGS had 848,000 dwelling units and the 2006 census counted 870,992 private dwellings, not including collective dwellings. It’s unclear to me why these differ so dramatically.

Employment counts are harder than they should be. Moreover, employment is probably not the most relevant metric, it would be better to count jobs. Which is even harder. As the RGS employment estimates are based on the census, we can query the employment variable by place of work geography. We get a total employment of 1,113,465 people in Metro Vancouver, compared to 1,158,000 from the RGS.

The match is reasonably good, although our census numbers don’t include the census undercount yet. Undercounts are only available for the place of residence, not the place of work geography, but that difference will have a negligible effect. An alternative is to use Labour Force Survey data that is available annually, but only considers place of residence instead of place of work. For 2006 that estimate comes out as 1,139,800 for the (unadjusted) employment in Metro Vancouver in May 2006.

To move forward, we will focus on the growth of our measures rather than the absolute numbers, as differences in sources and methods tend to divide out that way. As this is something that should be monitored on an ongoing basis we will be relying on the annual StatCan tables for population and employment estimates, rather than the census estimates.

However, when we need finer regional breakup we are confined to census estimates.

Checking in with 2011 data

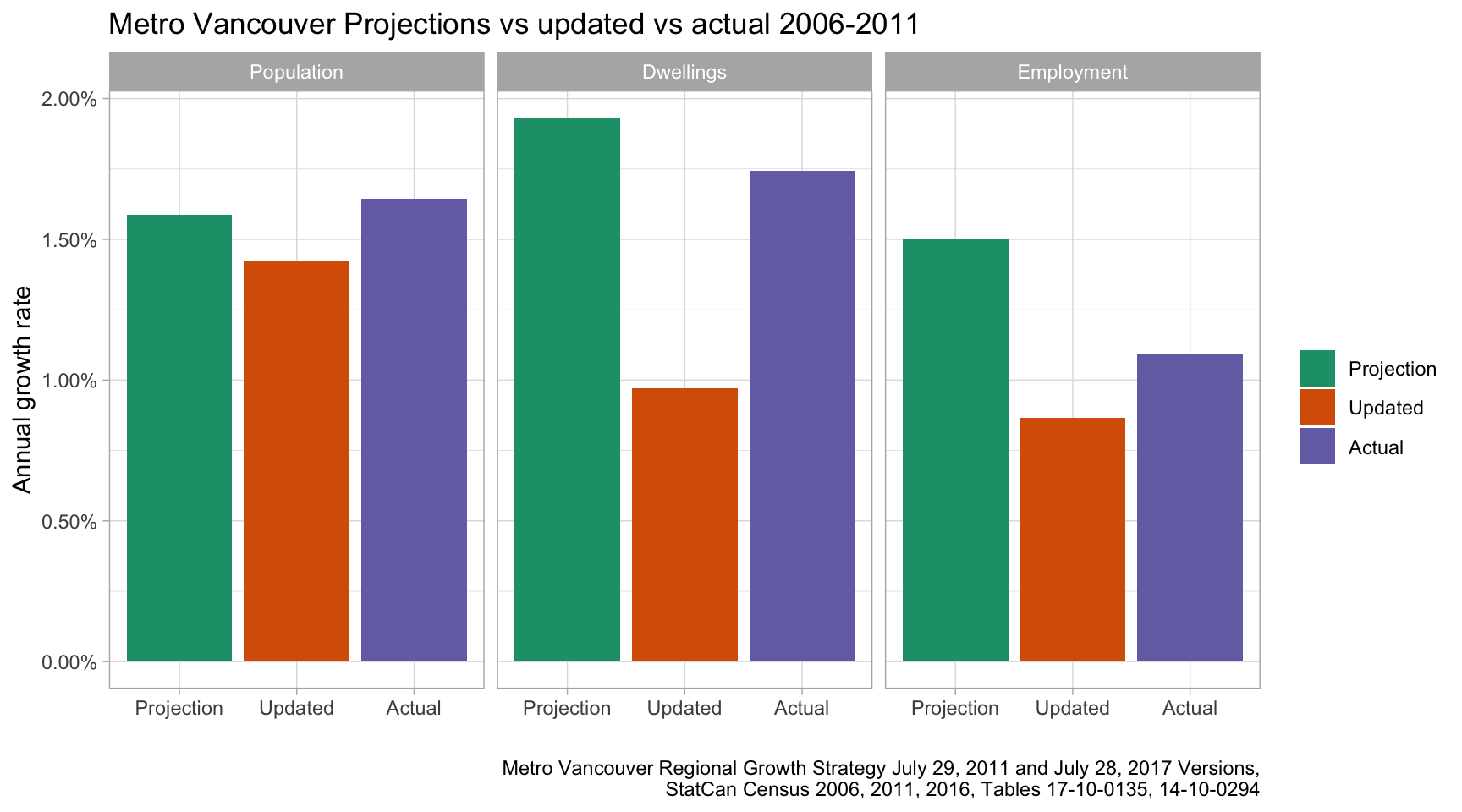

The 2011 Census data gives us the first reality check of the data. We use the baseline 2011 estimates from the updated Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy from 2017 as another point of comparison.

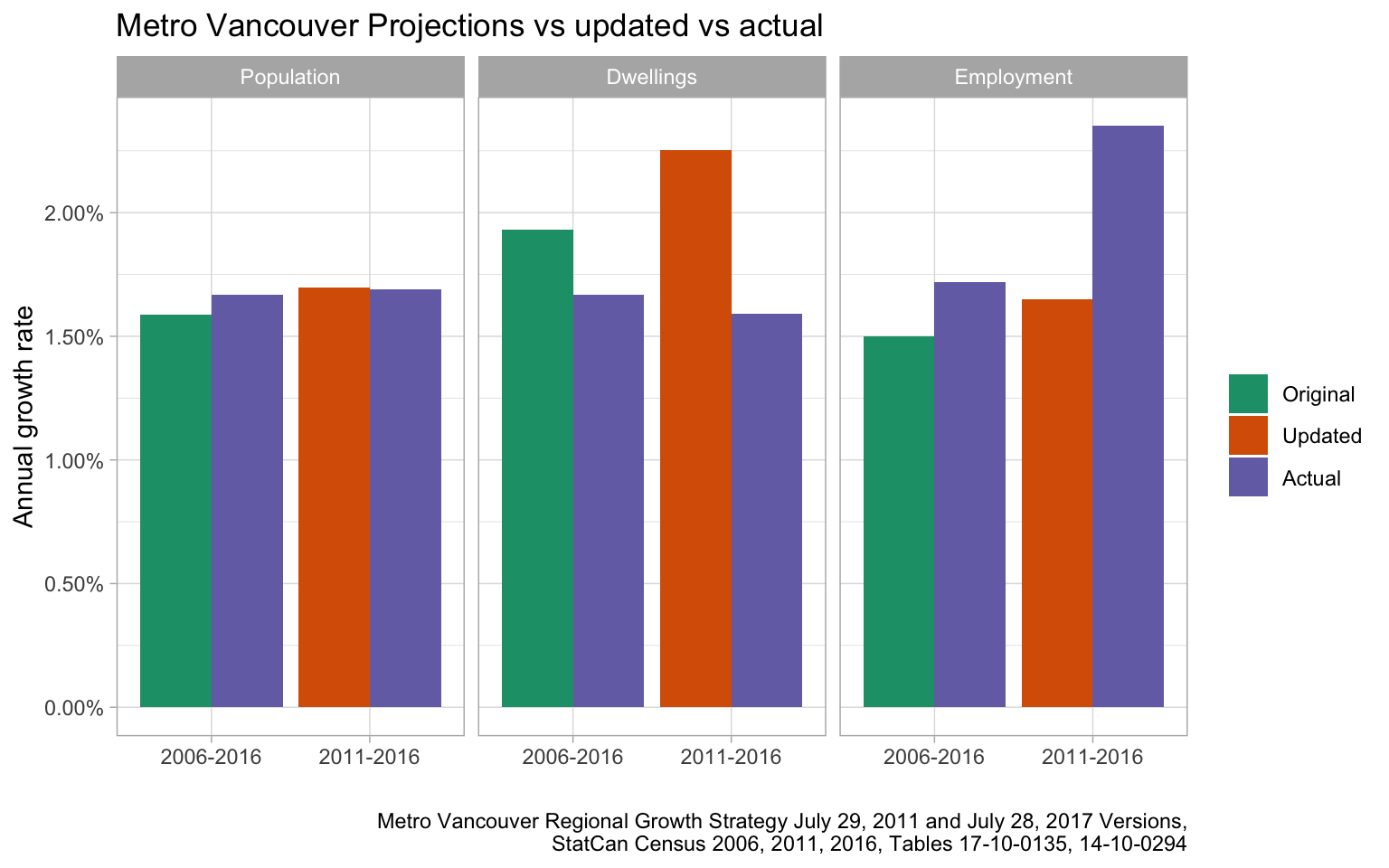

We compare the annual growth rates for the 2006-2011 timeframe as projected by Metro Vancouver in 2011 to the original 2006 base line and updated 2011 base lines, to the “actual” change based on Census (for private dwellings) and annual StatCan tables (for population and employment). Calling these “actual” is a bit ambitious, as we are glossing over details as we have explained above, but we will run with this for now.

What this shows is that population came in roughly as projected, whereas employment fell a bit short (which should not be surprising considering financial crisis hit in that time window). What’s a real head-scratcher is the change in dwellings, where projections came a bit short of the actual, and the two Regional Growth Strategy baseline differ significantly. This points to a change in methods in the RGS.

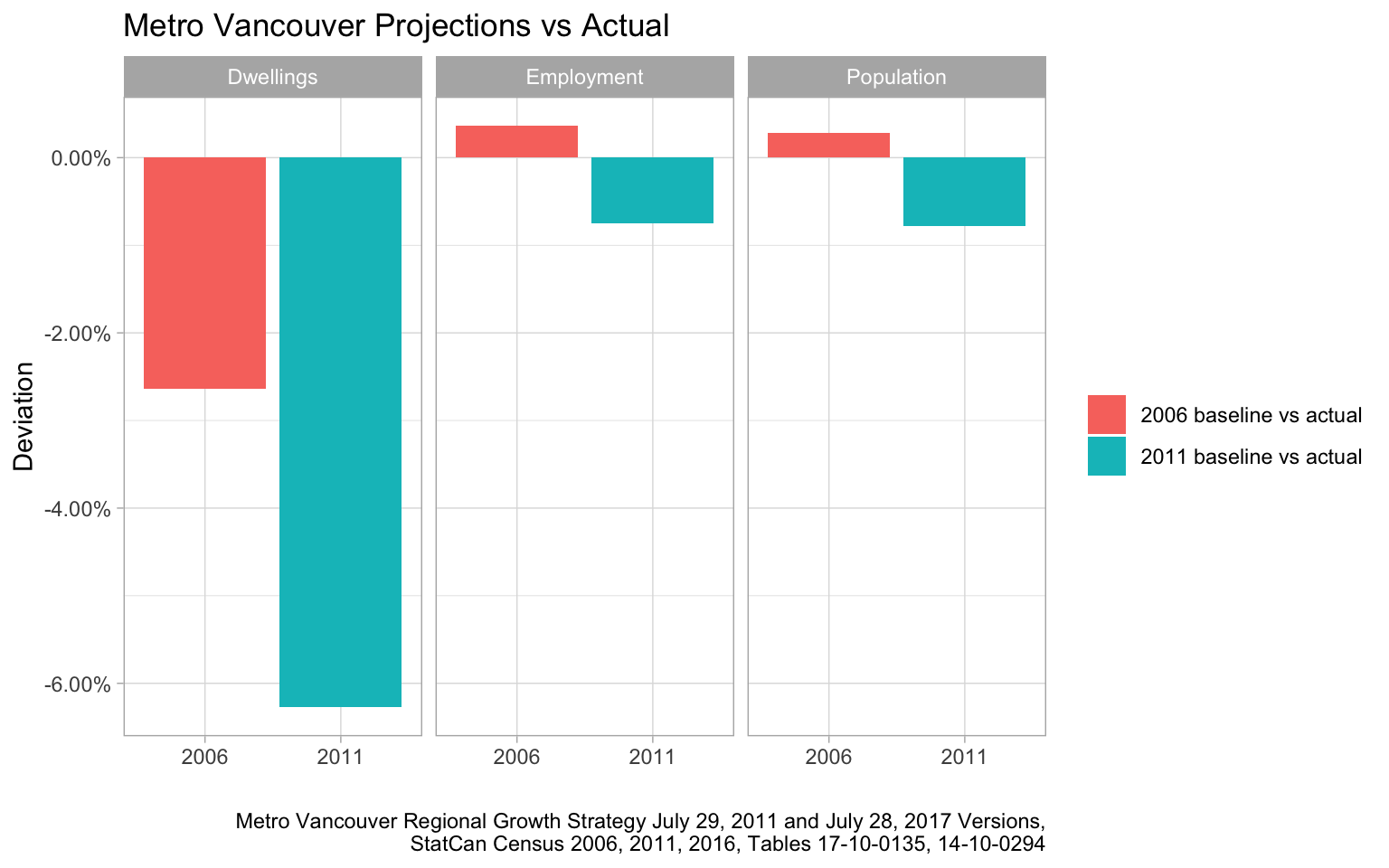

We can also look at how our population, dwelling and employment estimates line up with the 2006 and 2011 baseline estimates from Metro Vancouver.

This shows that the Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy did a decent job at projecting jobs and population, but came in systematically short of their dwelling targets. The smaller differences aren’t concerning and expected when using different metrics, but it would be prudent to better understand the apparent dwelling shortfall in the RGS. It would be good to better understand exactly how Metro Vancouver derives their estimates and projections.

Checking in with 2016 data

The 2016 census gives us another opportunity to check the projections against the data. We can use the projections from the original and the updated Growth Strategy and compare them to our estimates based on Census data and annual tables.

We see that the population grew faster than projected off the 2006 baseline, but a bit slower than projected off the 2011 baseline. Dwellings consistently grew slower than projected while employment consistently outperformed projections.

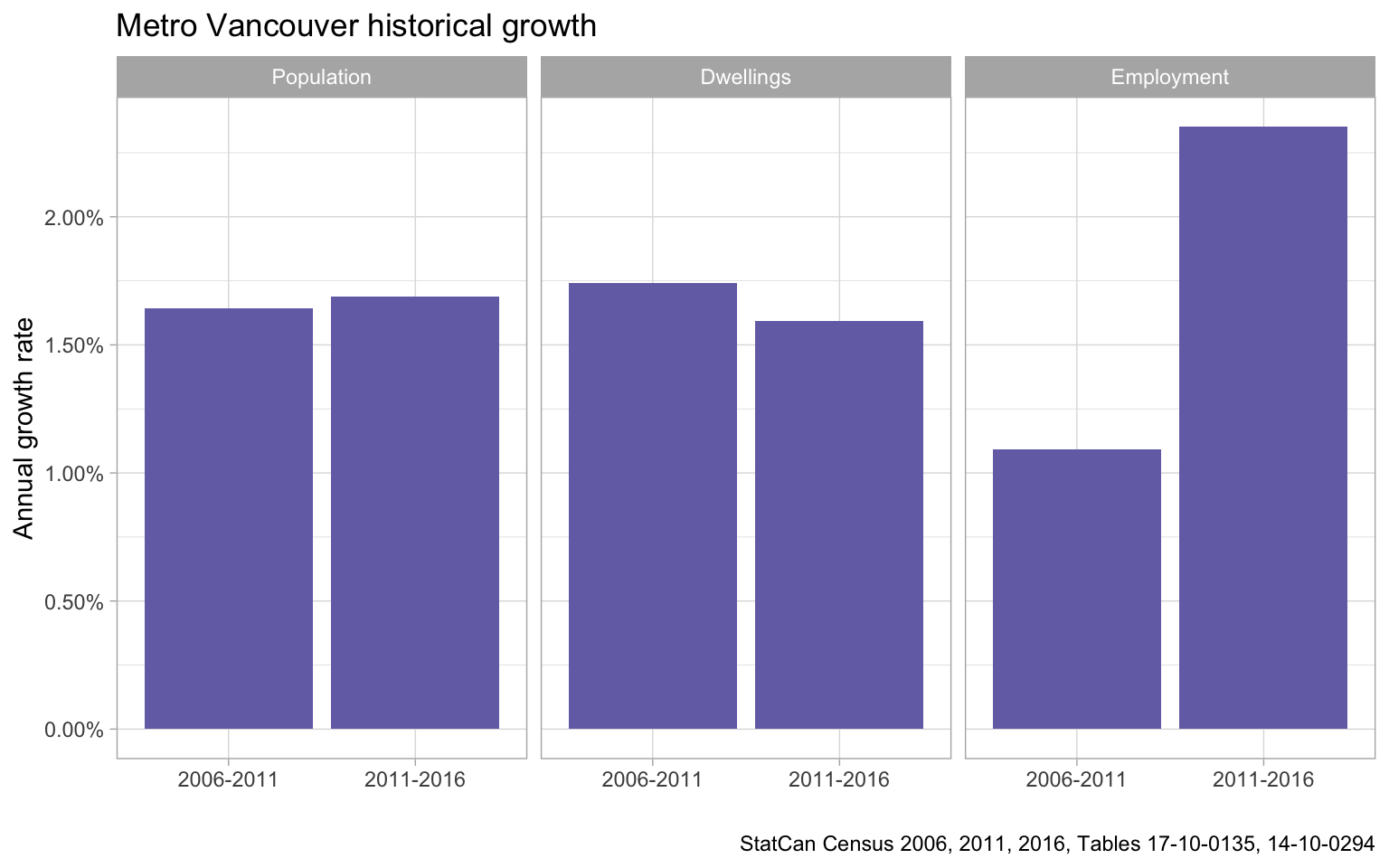

Another interesting takeaway from the data is to just look at the trend in our “Actual” data.

This shows that dwelling growth slowed somewhat after 2011, while population growth slightly increased and employment growth increased dramatically, recovering from the slower growth during the economic slowdown around 2008.

Regional breakdown

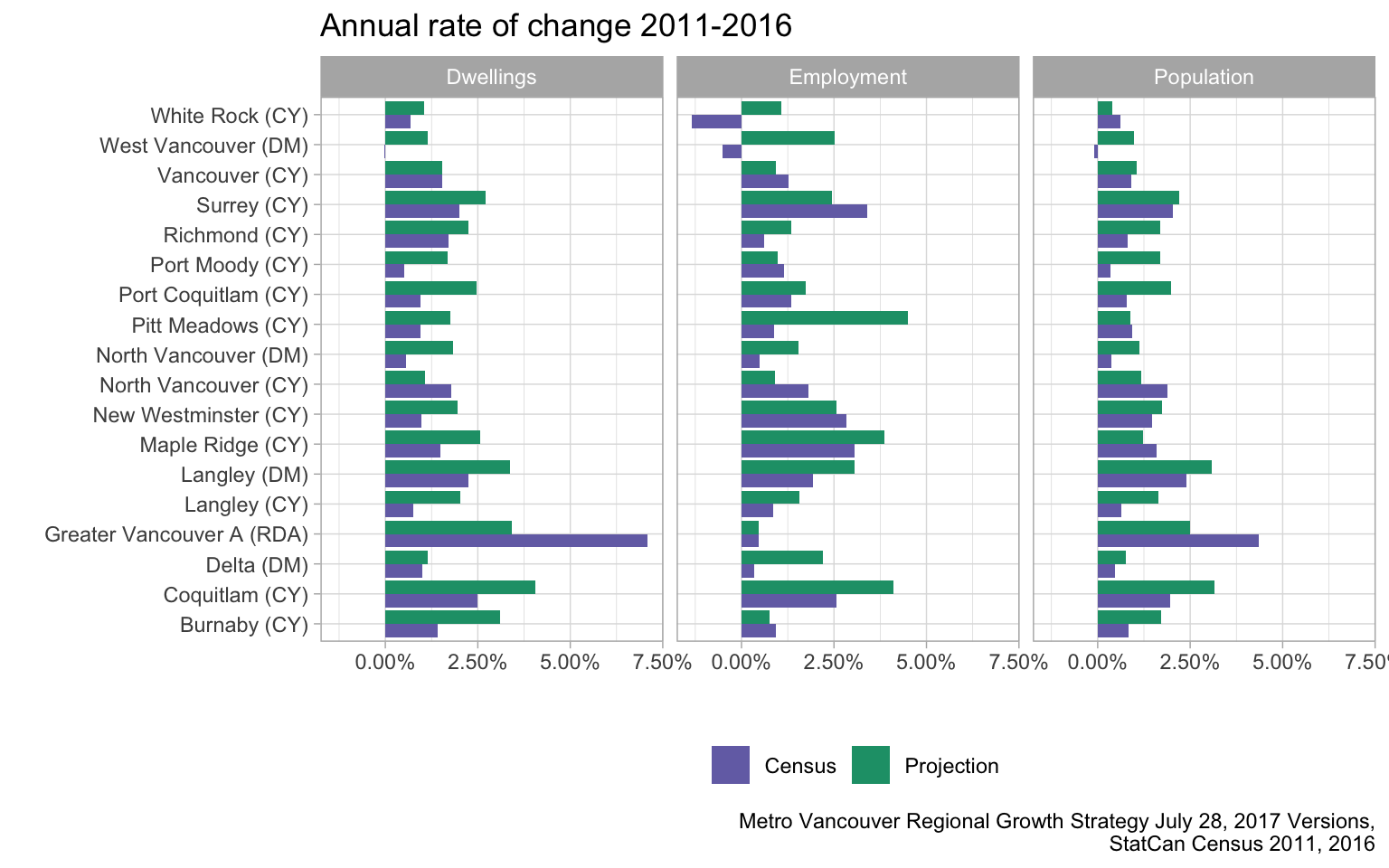

Another aspect of the Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy is the regional allocation of the growth. Here we are working exclusively with the updated Growth Strategy. For this we can’t get away with using annual population and employment data any more but have no choice but go with census data. This means we have to worry about census undercounts, but this is where things get tricky. Those estimates aren’t easily available at the municipal level, and one would expect significant regional variation that simply using metro estimates isn’t particularly informative. BC Stats has custom population estimates at the municipal level that include the census undercount, and StatCan probably has custom estimates as well. We will skip over this detail, the difference in census coverage rates between the census years should not impact our results by much.

Moreover, we can’t lazily assume that place of residence and place of work (roughly) coincides like we did when looking at the Metro level, we will have to be careful about how we count employment. Again, a custom tabulation would be helpful for this, but we will make due with adjusting employment numbers by net commuter flow between municipalities, recognizing that we are missing flows between municipalities with fewer than 20 commuters.

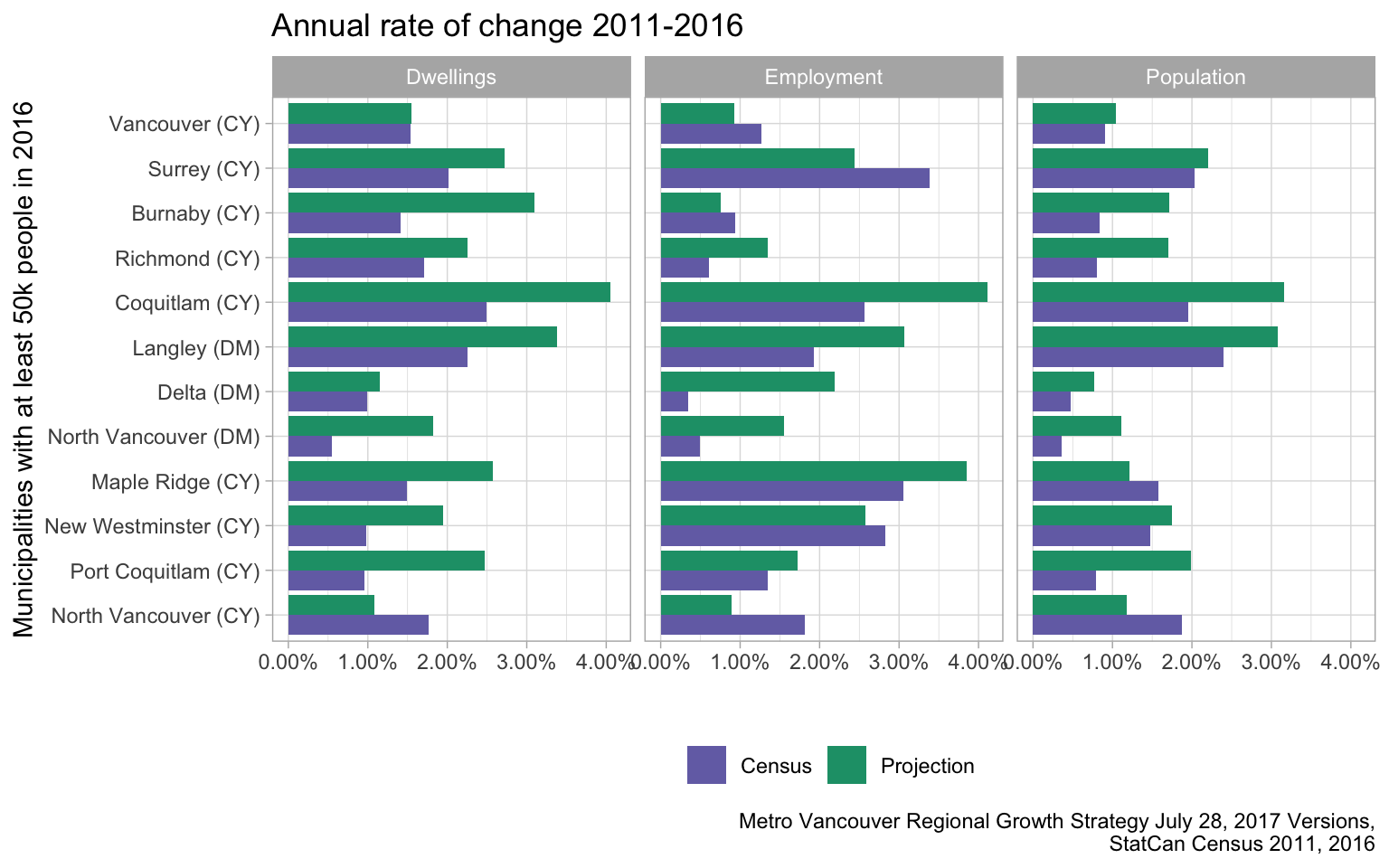

Again, projections are just projections, and our census numbers do not account for census undercounts, although most of these will divide out when taking differences. And our employment estimates, especially for smaller municipalities, should be taken with caution because our commute flow data dropped flows below 20 commuters. Thus it makes more sense to focus on the more populous municipalities.

The City of North Vancouver is the only municipality that exceeded its projections on all three metrics. The City of Vancouver, Surrey, New Westminister and Burnaby all exceeded their employment projections, while at the same time falling short of their dwelling (and their population) projections. All of the other larger municipalities, with the exception of Maple Ridge, came in below their projections on all three metrics.

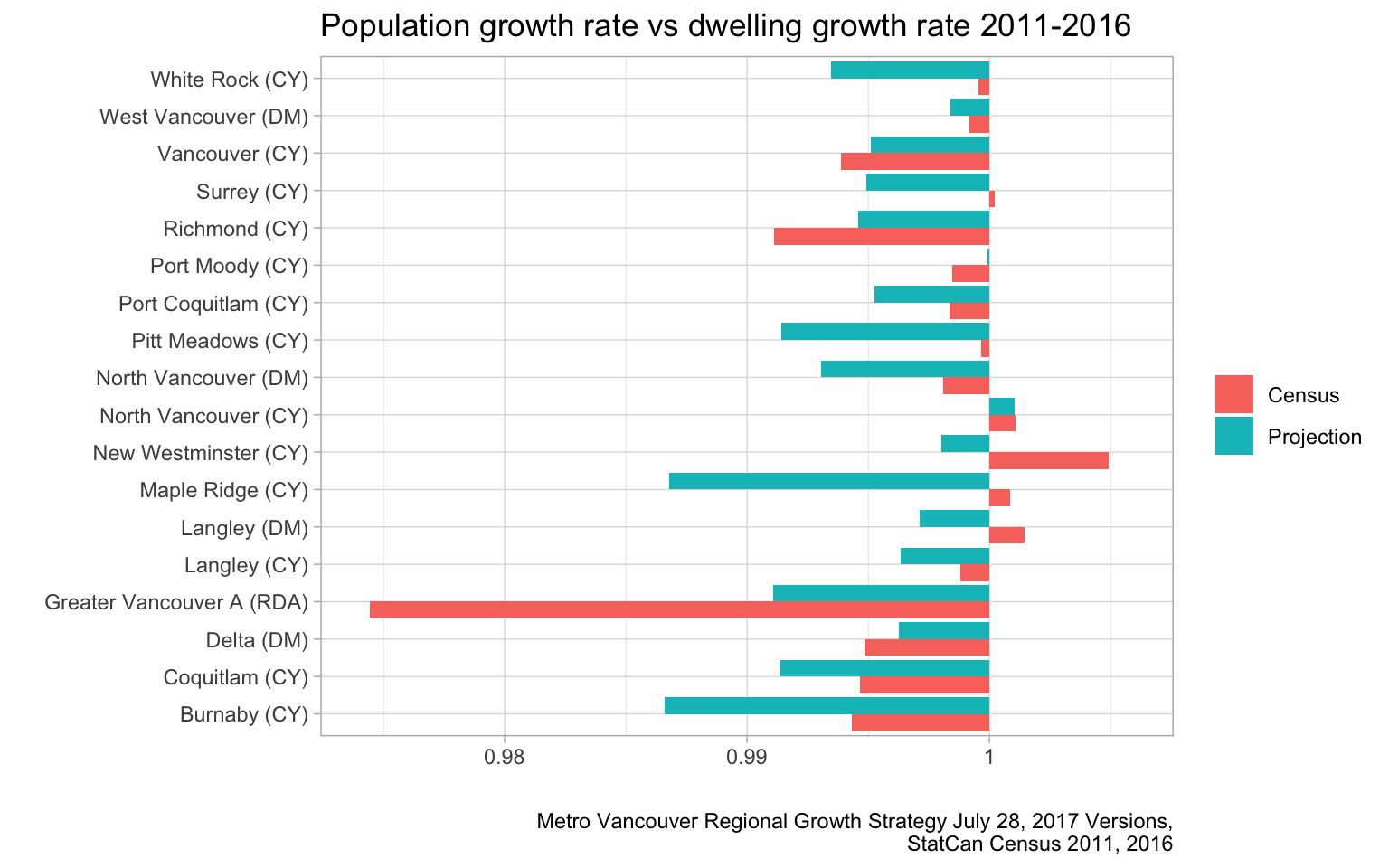

Unfortunately Metro Vancouver did not detail how they arrived at their projections, so it is difficult to read too much into this discrepancy. But it provides a good opportunity to re-evaluate the metrics and assumptions they are based on. What we do see is a very good correspondence between dwelling and population growth, as is to be expected.

Of particular interest is the relationship between these metrics, in particular the one between dwellings and population. It can be useful to break down population change into population change due to change in dwelling units, population change due to change in household size and population change due to change in the rate of unoccupied dwelling units as we have explained before, with each component mapped out across Canada.

Generally we expect population to grow slower than dwellings due to shrinking household size, but this is not always the case as the data shows. For example, household size increase in the City of North Vancouver, and the increase was large just enough to make up for a slight increase in dwellings not occupied by usual residents. Maple Ridge and the District of Langley on the other hand experienced a slight drop in household size, but this was more than made up for by a drop in dwellings not occupied by usual residents. New Westminster saw both, an increase in household size and a drop in dwellings not occupied by usual residents, which boosted the ratio. Our interactive map makes it easy to explore the reasons for these census ratios in the case of the population in private households only as well as in a more complex visualization for the entire population (which slightly changes the interpretation for Maple Ridge, presumably due to an increase in collective dwellings).

We should point out that for Electoral A there has been a significant number of reclassification from collective to private dwellings within parts of UBC student housing that register as unoccupied by usual residents in the census, as well as significant new construction, both of which add to “unoccupied” dwellings and drag down the ratios from the census shown in the graph above.

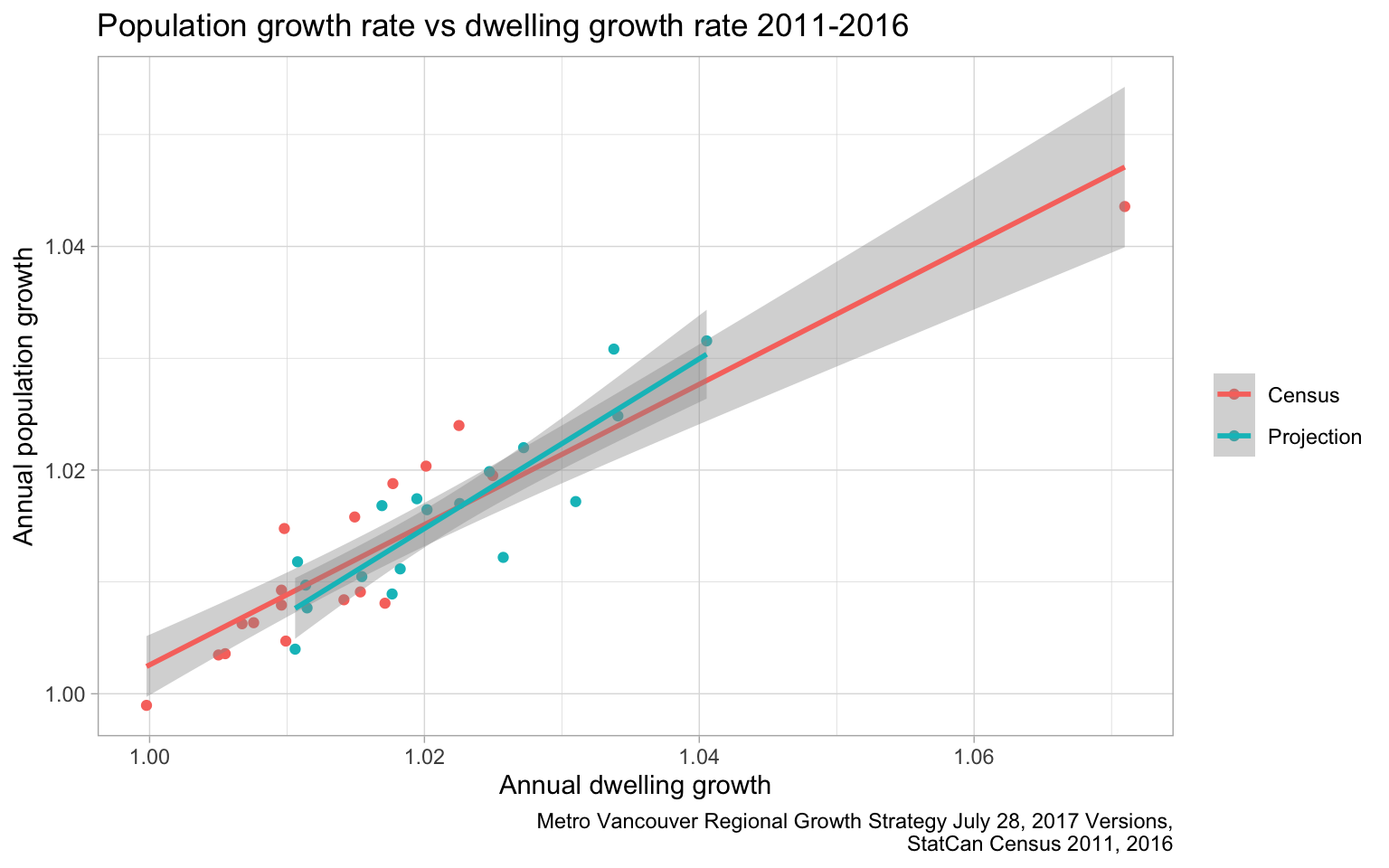

To quantify the relationship between population and dwelling growth rates we can fit a simple linear model to the RGS targets, as well as to growth rates derived from census data.

Census data gives a better fit than to the RGS projections, with an adjusted R2 of 0.849 for census data and 0.776 for the RGS. This points to room for refinement. One should be able to improve the model fit by accounting for collective dwellings, as well as number of units completed in the months before census day for each of the census years, which has a noticeable impact on the number of unoccupied units as we have explained before. A more detailed understanding of the number of bedrooms of the added (and lost) dwelling units, as well as tenure, is a great predictor of household size, information on the mix of bedrooms should give another significant boost to improve the model fit. Lastly, we need to recognize that change in wealth is another measure, as change in wealth is generally associated with consumption of more housing (and shrinking household size).

The takeaway is that the relationship between new dwelling units and population growth is very predictable, and in our supply constrained market we find that population growth is constrained by dwelling growth.

Planning for the region

Dwelling growth in our region is highly regulated. The Regional Growth Strategy is only a guiding document, but it is often used as a plan that allocates growth to the region overall and distributes it within the region.

We have already seen that there are significant latent population pressures, partially due to dwelling growth targets set out by the Growth Strategy not being met, and partially by these targets likely being too low. Here we want to focus on how the Growth Strategy is distributing that growth, and how that might relate to people’s preferences.

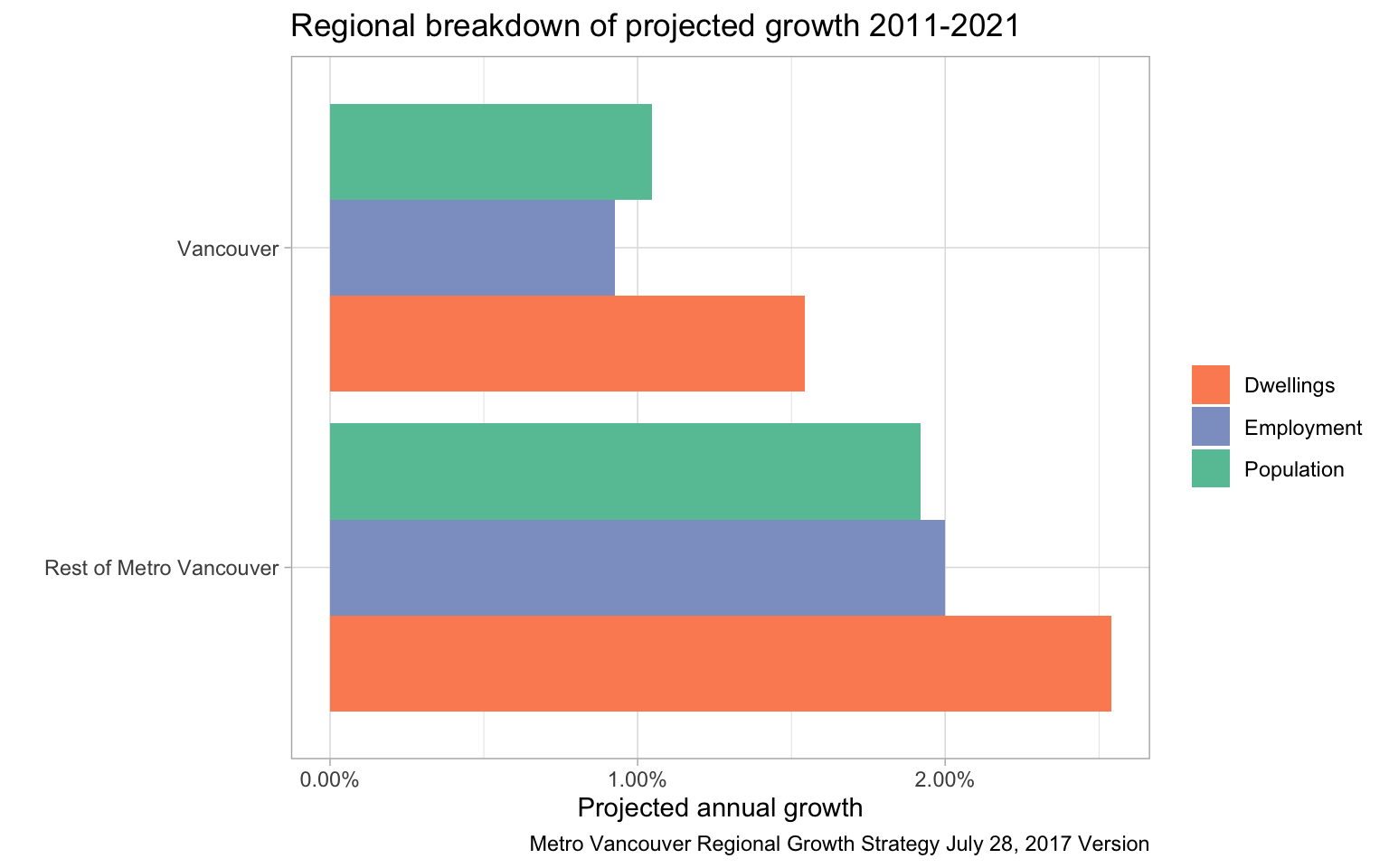

We have already seen above that the projections assume stronger growth in some of the outlying regions than in some of the central regions. To bring this out more, we compare the projected growth in the City of Vancouver to the rest of Metro Vancouver.

The Regional Growth Strategy is projecting that the City of Vancouver will grow slower than the rest of the region. This makes sense if we assume that, on balance, people would rather live further out than they do right now. But I all evidence points toward the opposite being true, that is that people would, on balance, rather live in the City of Vancouver than in more outlying municipalities. Allocating growth in direct opposition to people’s preferences serves to drive up prices and rents in the central areas, and to drive low income people out. Which is exactly what we have seen when looking at income data where incomes have rising much faster in the City of Vancouver than in Metro Vancouver overall, with the higher income brackets growing faster and low income brackets dropping faster in the City of Vancouver.

Upshot

The last two sections illustrate two main dangers of an overly restrictive planning regimen.

- When planners don’t manage to hit their dwelling targets, or set their dwelling targets too low, we end up with higher population pressures and hit labour market constraints.

- When planners don’t manage to allocate the growth within the region according to people’s preferences, it will create artificial price gradients and push people out of their preferred areas and lengthen commutes.

Both of these outcomes have strong negative consequences for individuals, as well as the for the region overall. This is why it is very important that planners pay close attention to early warning signals of dwelling shortages as well as within-region location preferences.

More transparent models would also be helpful, especially given how high the stakes are when the dwelling targets are set too low. It would be helpful if planners, maybe in conjunction with economists, could explain better what consequences different planning scenarios may likely have for the region, so the politicians and the general public can make better decisions on how the region should grow.

In our highly regulated environment it is prudent to develop better metrics that can be updated regularly and that help inform of region-wide housing shortages, as well as more localized housing shortages within the region. Recently Nathan Lauster and I set out to draw up an outline of how such metrics could be constructed, a task we are planning on following up on with more concrete metrics and code that implement them.

As usual, the code for the analysis is available on GitHub.

Reuse

Citation

@misc{on-vancouver-population-projections.2019,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {On {Vancouver} Population Projections},

date = {2019-08-01},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2019-08-01-on-vancouver-population-projections/},

langid = {en}

}