There are many useful metrics to understand neighbourhood change, change in the income distribution, change in the share of population in low income and change in dwelling units, change in households who rent, or just overall population change and how that relates to zoning. All these tell us something about how neighbourhoods change, the metric we want to focus on in this post is the number of children under 15.

Children under 15 years of age tell us something about now demographic renewal works in neighbourhoods, about demographic sustainability. Some neighbourhoods have more children than others for a variety of reasons, ranging from preference to built form of housing. If a neighbourhood is dominated by 1-bedroom dwelling units there will be few children living there. What we are interested in in this post is how this changes over time, which neighbourhoods are gaining children and which ones are losing children? And why?

There are various processes that impact how the number of children in an area changes over time. Children get born to (or adopted by) families living in an area, and families with children move in and out of neighbourhoods. We will look at these two processes separately in another post, in this one we focus on the “renewal” aspect and the change in the number of children under 15 in each region, which combines these two effects. But before that we remind ourselves just how mobile residents of cities are.

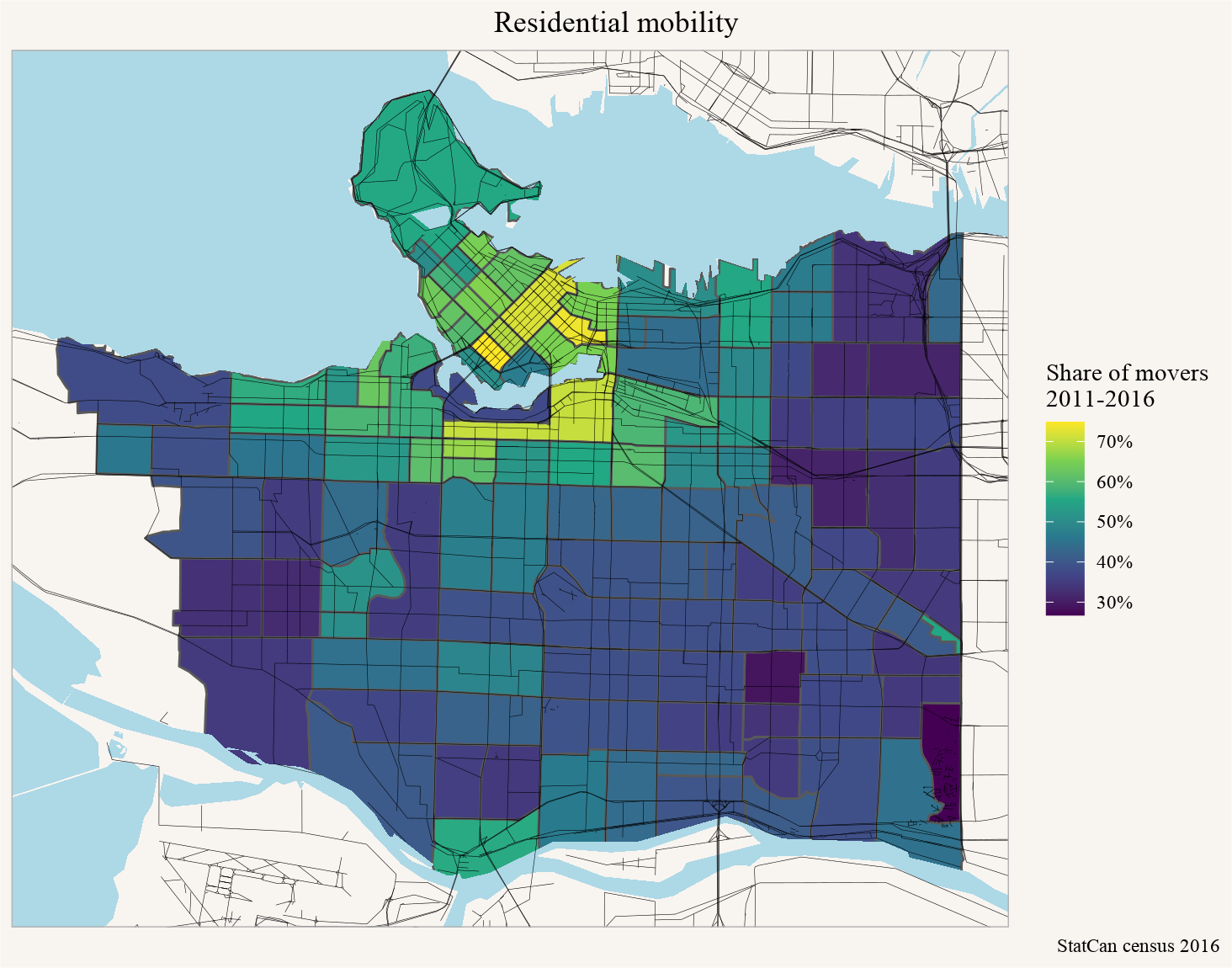

Residential mobility

A little under half of the residents (5 years or older) of the City of Vancouver lived at a different address five year prior, making residential mobility is a significant driver of neighbourhood change. It’s instructional to take a quick look what residential mobility looks like across the City of Vancouver.

There is significant variation in overall residential mobility, with the overall share of people that moved in the past five years ranging from just under 30% to over 70%, depending on the neighbourhood.

The difference in mobility has many reasons. Some are demographic, for example young people move more frequently than older people, so areas that attract a younger demographic will see higher rates of movers. There are also physical factors at play, for example when larger apartment buildings get built everyone in the new building will have lived in a different address five years prior.

But even the people that stay fixed at the same address between census periods change, they get older. These two processes, residential mobility and aging, and how they interplay with housing, determine how the age profile of a neighbourhood changes between census periods.

Children as an indicator of demographic renewal and sustainability

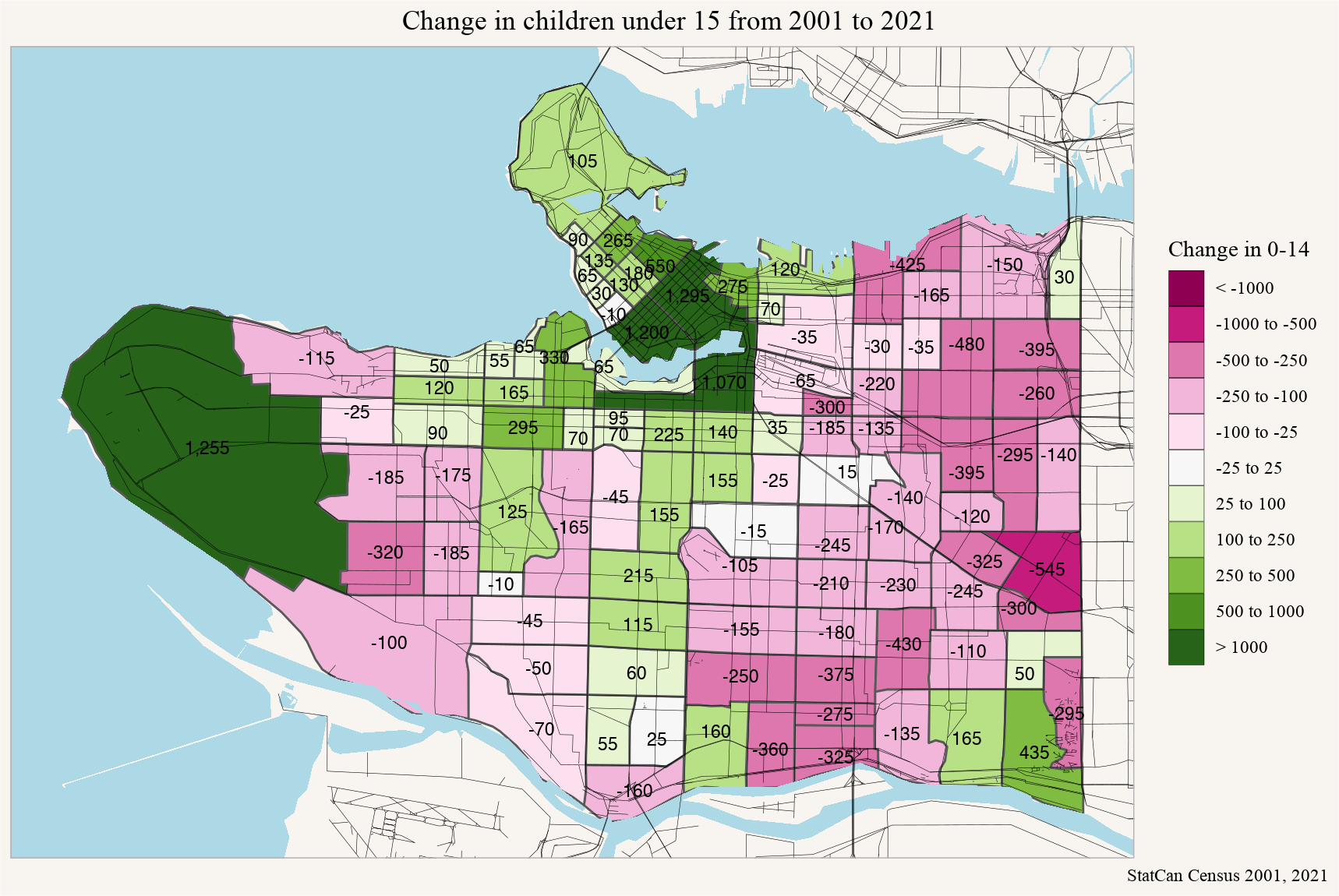

Overall population change shows us which areas are growing or declining in overall population, focusing in just on children separates out growth that is driven by other age groups, for example by growth in older populations. As people are living longer and the key demographic cohort of baby boomers is entering retirement age, children often get squeezed out. This process happens over the course of several census periods, we will look at the 20 year timeframe from 2001 to 2021.

For technical reasons we need to include Musqueam 2 into this because they did not have a separate census tract in 2001 and got lumped in with the neighbouring City of Vancouver census tract, and for good measure we add in the Point Grey Peninsula to the west that’s home to UBC, UEL and the UNA.

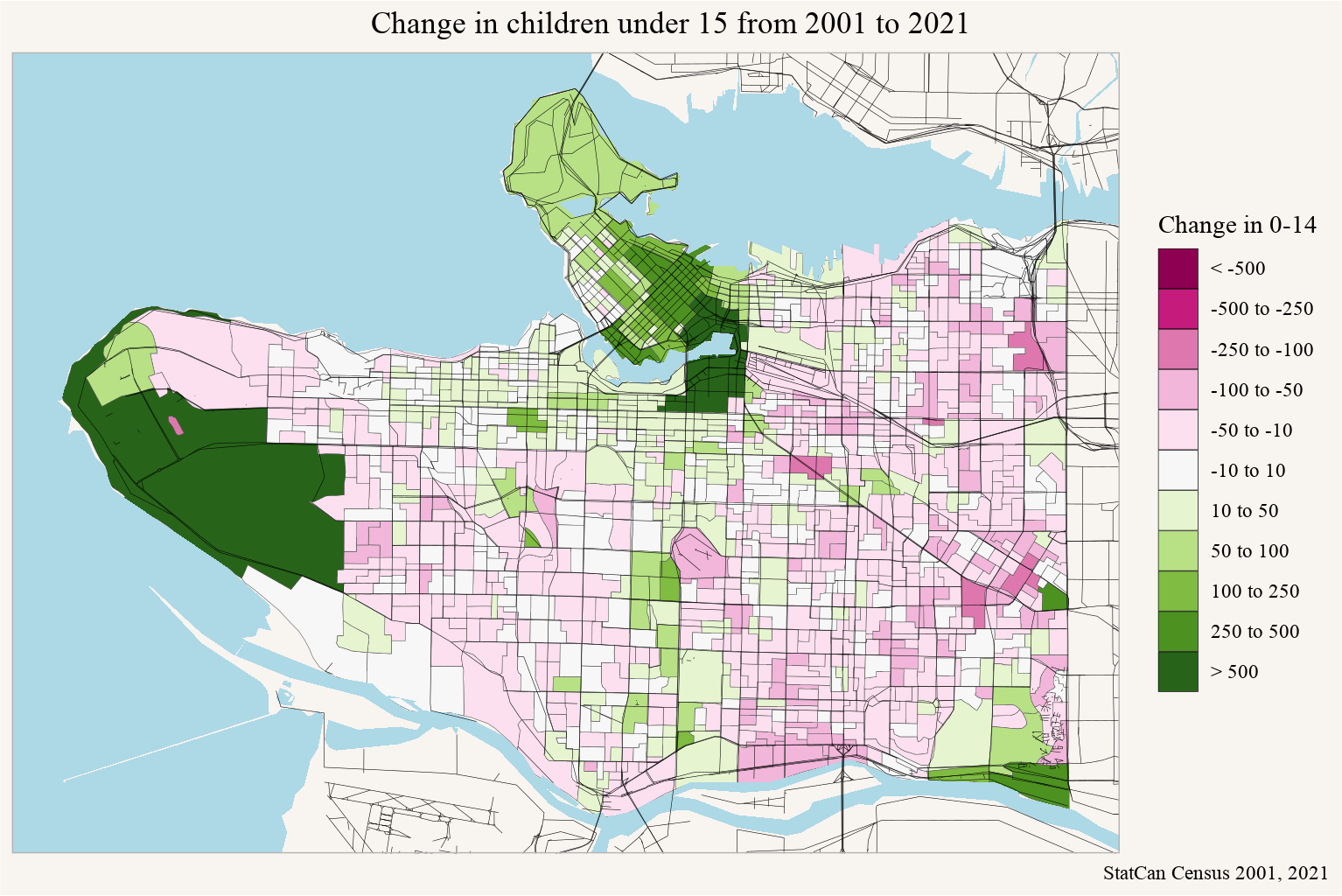

This shows that our city has been quite divided, with some areas gaining a lot of children, and others losing children.

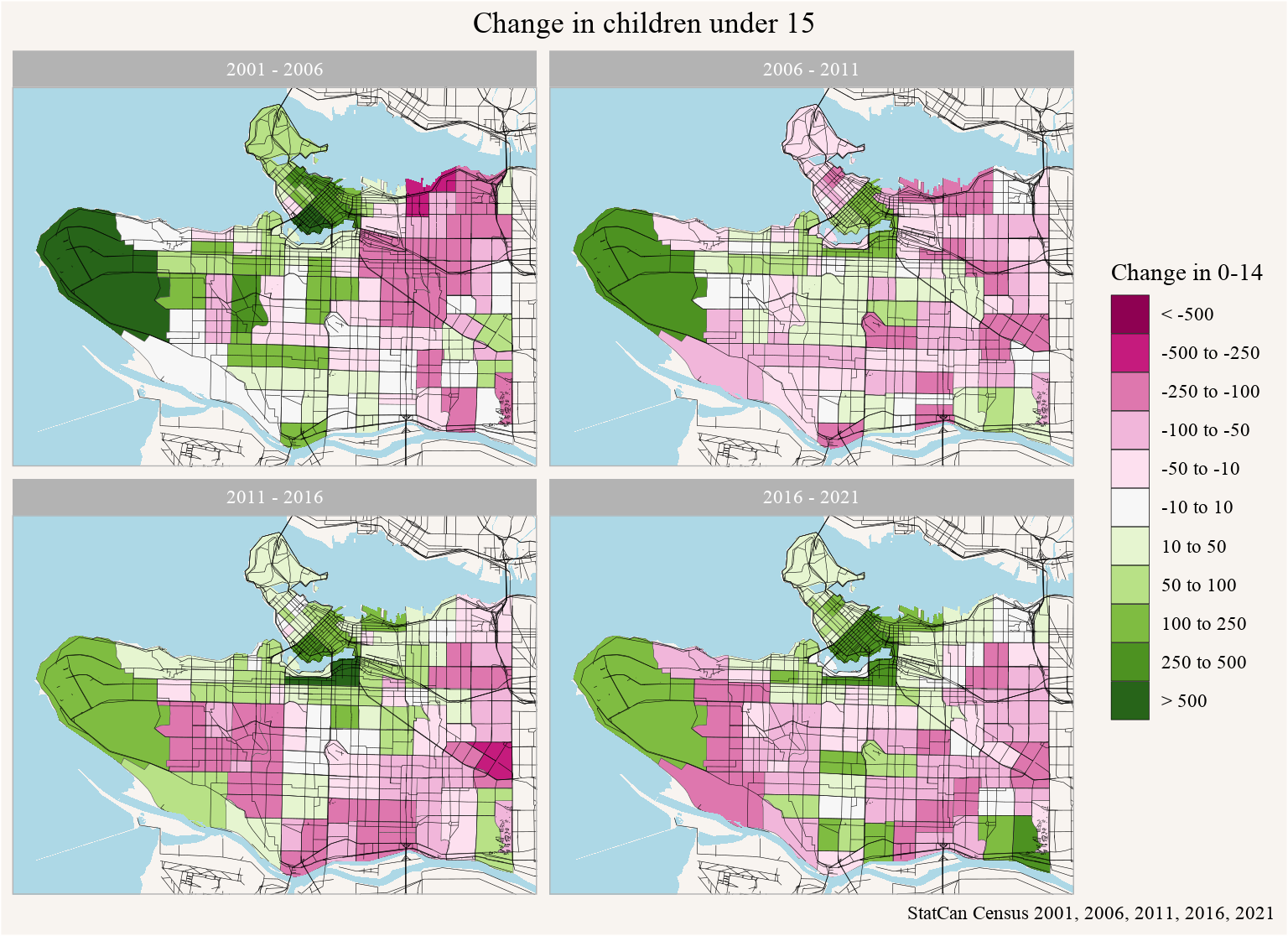

We can split this up in several ways, first taking a look at the inter-census periods separately.

That helps us see which areas show chronic census over census declines in the number of children, which ones saw sustained increases, and which were wavering.

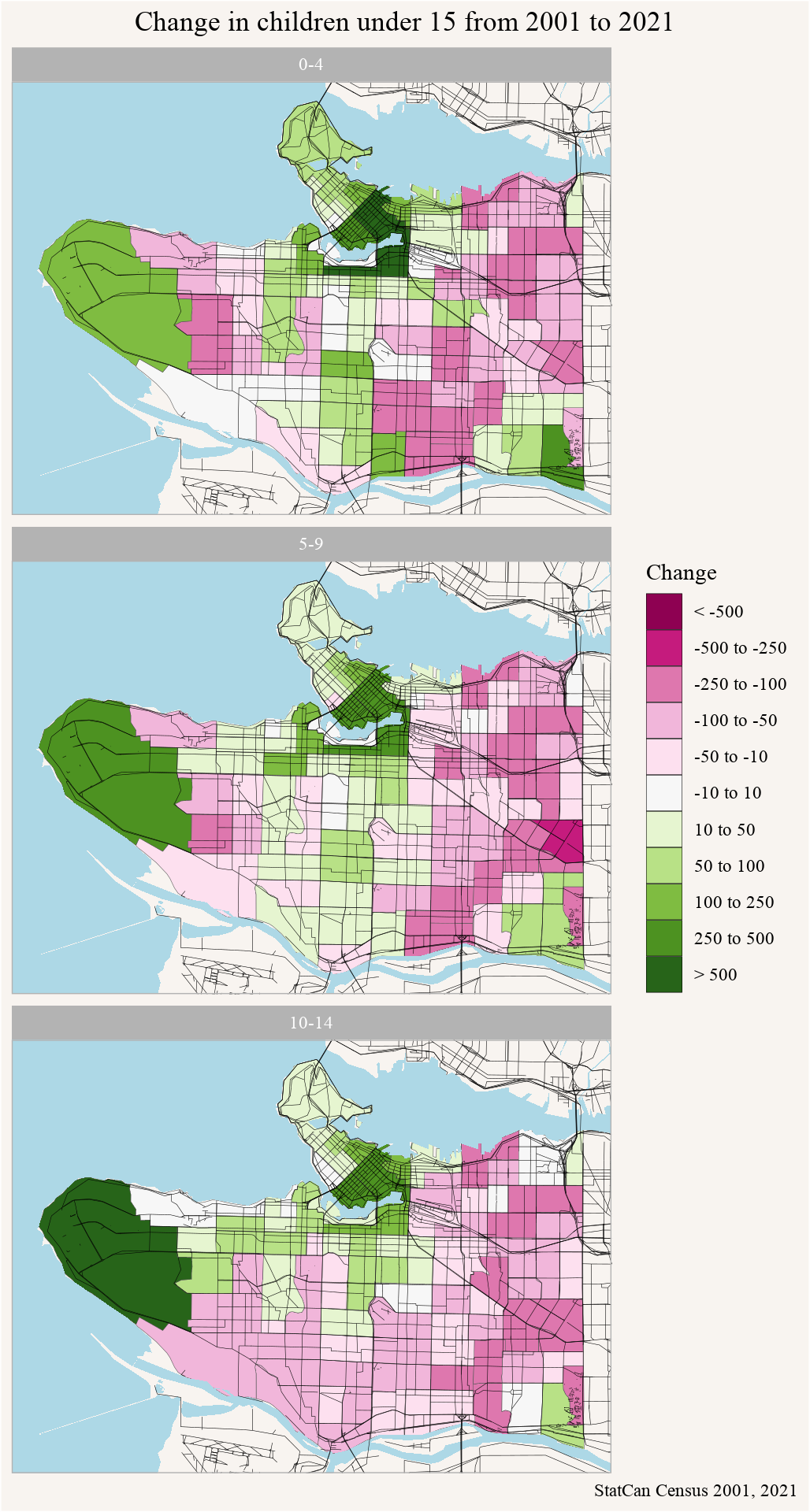

Another way to slice this is to look at each 5-year age group separately.

While there is a lot of similarity in growth across these age groups, it’s noticeable how growth in 10-14 year olds is more geographically constrained.

Children are good, actually!

When it comes to neighbourhood change we often ask if change is good or bad. And more often than not that’s ambiguous. A changing physical housing stock is perceived as bad by people attached to the existing physical form and as good by people looking for housing options that the existing stock does not offer. Overall population (and housing) increase is sometimes viewed as good, sometimes as bad, and at other times conditioned on who moves into new housing, with some people questioning who new housing is for, signalling a desire to control who moves into new housing. Increase in overall income in a neighbourhood is sometimes seen as a positive sign of growth, sometimes negatively as a sign of gentrification.

But children take a somewhat unique position in that they are almost universally seen as good, and a decline in children is seen as bad.

What causes change in children?

This leads to the question what kind of policies are impacting whether children row or decline in a neighbourhood. Looking at the images above an immediate candidate comes to mind. Housing. A key observation is that there are several processes that, assuming a the housing stock remains fixed, combine to work at reducing the number of children

- As Canada’s population ages and the age distribution shifts a lower share of homes will be available for young families. We get more one or two person households in single family homes now that we used to, and people may choose not rent out secondary suites they may have if they don’t need the income.

- Vancouver makes up the central part of the metro region, and central areas generally attract a lot of young (childless) professionals aged 25 to 34s. And with the outer parts of the region growing faster than the City of Vancouver (by design, that’s what the Metro Vancouver Growth Strategy is calling for) the City is becoming increasingly more “central” and not just the number but also the share of these young professionals has been growing. Which again leaves less space for young families in their late 30s and 40s, which is amplified by overall demographic shifts in the region and Canada overall.

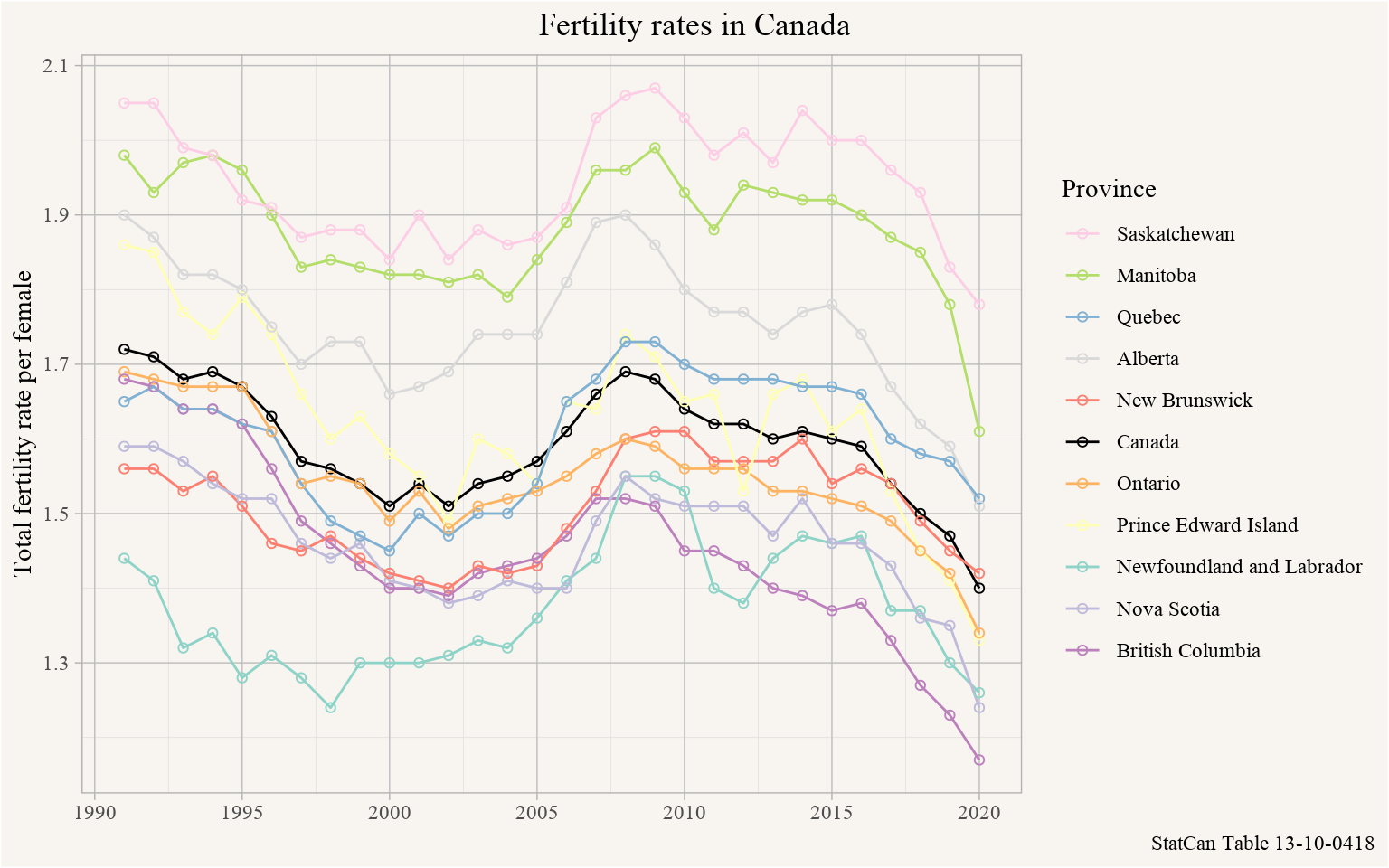

- BC has seen declining fertility rates of this time period and now has the lowest fertility rate in Canada, which is likely not independent of the other processes noted here.

- At the dame time, as people get richer they tend to consume more housing. Richer people are less likely to rent out a secondary suite (assuming they have one), and they are less likely to down-size or right-size their housing (having extra bedrooms is nice).

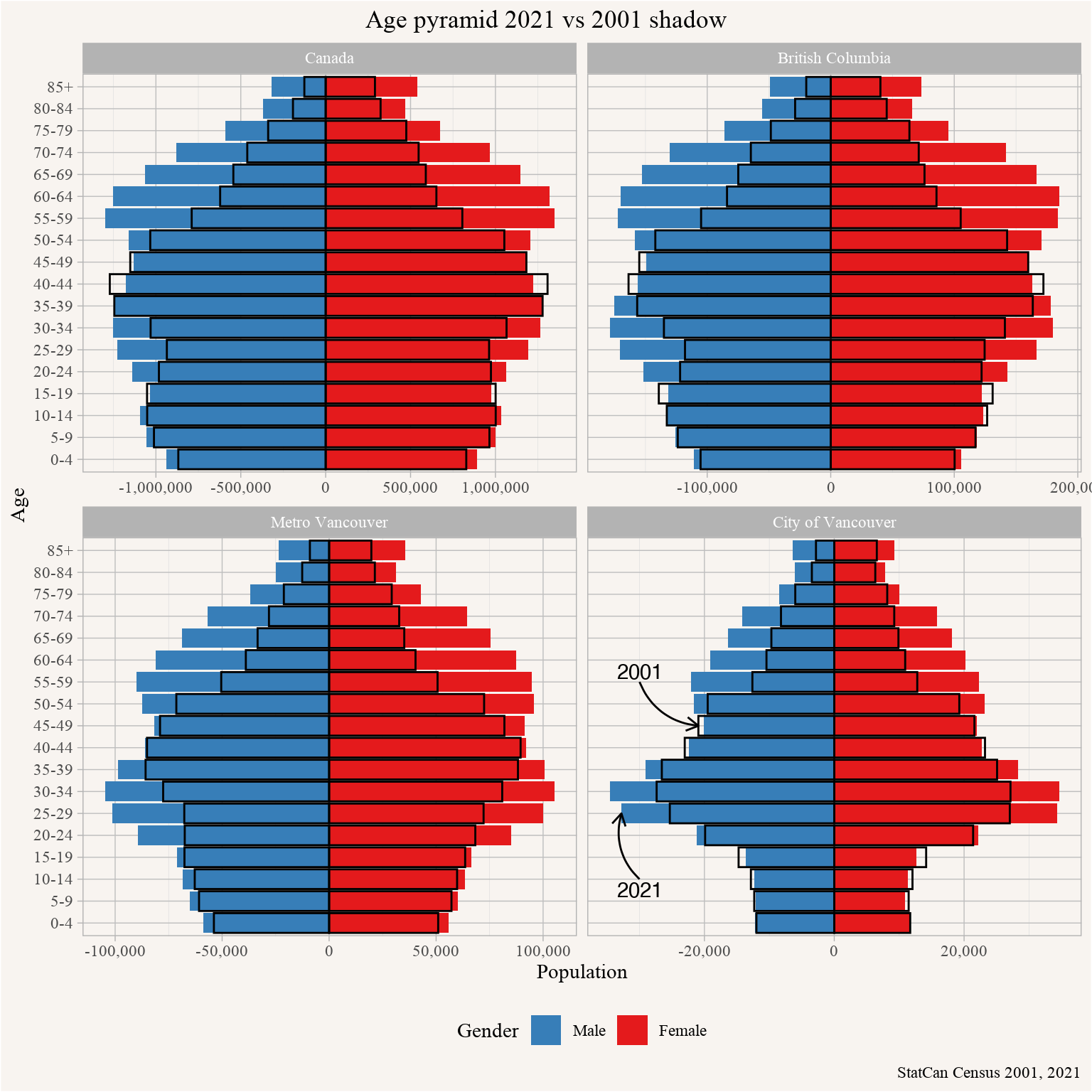

The first two demographic processes are demographic and we van visualize their effect by comparing the 2021 age pyramid of the City of Vancouver against their 2001 shadow, contrasted by Metro Vancouver, British Columbia and all of Canada.

Here we can observe several demographic trends combining. At the overall country level we can observe that Canada now has fewer people in their 40s than it did 20 years ago, this is part of the Gen-X demographic dip of people who were in their 20s in 2001, where can can identify the same dip (wedged between the Baby and Echo-Boomers). That Gen-X cohort did get boosted by immigration, but not enough to make up for the large number of boomers that have aged out of that age group between 2001 and 2021. We see very similar effects play out in British Columbia.

At the Metro Vancouver level in-migration was strong enough so that all age groups have gained, but the Metro region was growing faster (by design) than the City of Vancouver where that Gen-X cohort (and their children) got squeezed out. At the same time we see that the 25 to 34 year old age group has gained in prominence in the City of Vancouver, speaking to the big in-migration draw of the city for young professionals.

On net, for the City of Vancouver we have strong increases for population around 30, as well as the population 50 and above, squeezing out people in their 40s and children.

The third demographic process does not just touch Vancouver, but also shows up in province-wide numbers.

In the early 90s BC’s fertility rate was close to the Canadian average. After an initial dip the Canadian fertility rate recovered again around 2008, but at that point BC’s rate had already dropped significantly and showed a much smaller recovery. After 2008 the rates further declined, a trend that is driven by BC’s large CMAs with Victoria and Vancouver having a total fertility rate of 0.95 and 1.09, respectively, which is due to a range of demographic factors, but likely also at least partially impacted by the strong evidence of delayed household formation due to unavailability of housing in Vancouver.

These demographic processes combine with, and are partially caused by, the economic process to squeeze out families. But there is a way out: Add housing. If we add housing, we can make up for the demographic and economic shifts and provide space for families, and their children.

At least in theory. To investigate this in more detail we can look at the change in the number of children at a finer geographic resolution.

This shows us at a more granular level where children have grown and where they haven’t, and how that might relate to housing. Olympic Village and Yaletown light up, both areas where we have added housing. Similarly the River District, properties along the Cambie Corridor, Joyce Collingwood. And the little triangle at Arbutus and 33rd that got rezoned around 2003 pops out, as well as some other spot developments across the city. We also see some change along arterials where we have added housing above commercial spaces. And of course the UBC area, where the UNA saw an explosion in housing over this period.

Housing

Which brings us to the question of where we added housing in this timeframe. We can approach this from two angles, one is looking for housing built after 2001, and the other is to look at zoning changes since 2001. We will go both routes, each has it’s own advantages and disadvantages. Looking at housing being built since 2001 we will catch a lot of 1:1 replacements of single-detached houses. Looking at zoning we just capture where housing has been allowed to go, not where it actually went. Except that in Vancouver zoning is tight, essentially no multi-family housing (the only way we add housing in appreciable ways) gets built without a rezoning or at least conditional approval by the director of planning. And the areas that conditionally allow adding multi-family housing are also quite limited.

For this part of the analysis we will focus on the City of Vancouver and disregard Musqueam 2 and the UBC area as we don’t have historical zoning or (openly available) building age data for those regions.

Zoning

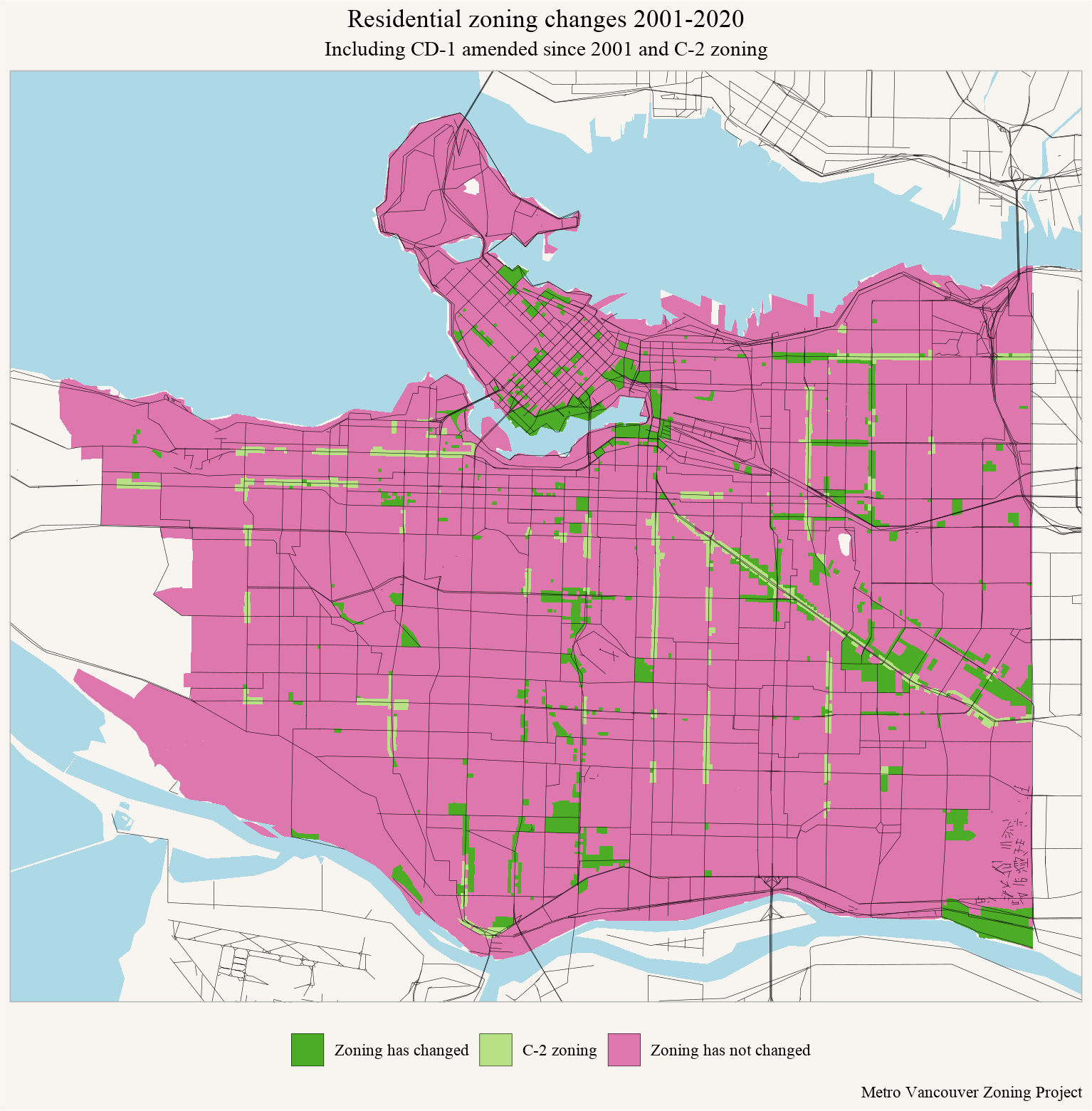

Let’s start with zoning. We have already looked at how zoning relates to overall population growth in Vancouver, but now we will refine this looking more specifically at change in zoning and how that relates to children. The idea is that it’s not so much the current zoning that determines how cities change, but if the zoning allows adding housing. Which in Vancouver mostly boils down to looking at where zoning has changed.

Drawing on our Metro Vancouver Zoning Project, in particular the historic zoning of the City of Vancouver we show all areas that have been rezoned to allow more housing since 2001. We also scraped the CD district schedule to include CD districts that have been amended since 2001, as for example has been the case with the “triangle” at Arbutus and 33rd to enable denser housing.

If this map looks rather scarce, then that’s because it is. The only actual rezoning that is not a spot-zoning in this time period is the RM-7 at Renfrew-Collingwood, but looking at the change in children map it does not seem to have resulted in a net increase in children. We will revisit this when looking at buildings by age.

Building age

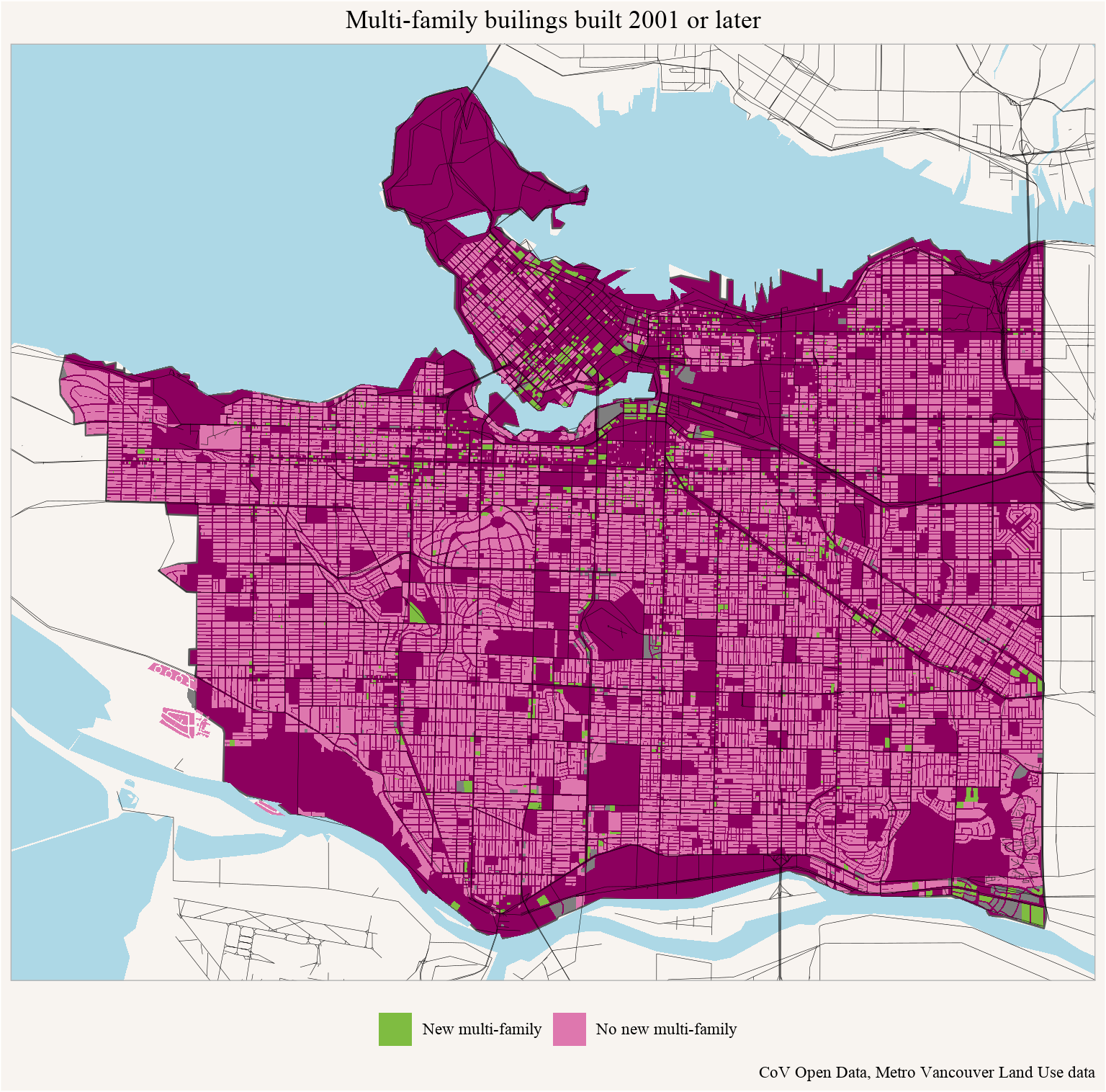

Another way to look at this is by building age, and our interactive map of Vancouver properties allows us to specify dynamic age cutoffs to investigate this. However, most new buildings are unproductive 1:1 replacements of single family homes, so it’s more useful to look what happens when we filter them out. Our land use data on these online maps are a little bit outdated, so we will make some fresh maps here.

However, even the newer Metro Vancouver Land Use data is already out of date and might miss some recent rezonings, so we also fold in the zoning data to make sure we can capture recent rezonings. This process would be a lot easier if we could just use the more detailed BC Assessment Roll Data, but unfortunately our province still believes that provincial housing data should not be openly available but be sold for revenue generation or available under strict NDAs, which is not worth the trouble for a blog post like this.

This gives a much more pinpointed view as to which property parcels saw new multi-family development. They don’t match up perfectly with rezonings, but the correspondence is quite good. The addition of new multi-family housing in C-2 zones, as well as Renfrew-Collingwood’s RM-7, is quite sporadic though, as one would expect when comparing the effects of rezonings to the conditional zoning under C-2 and RM-7.

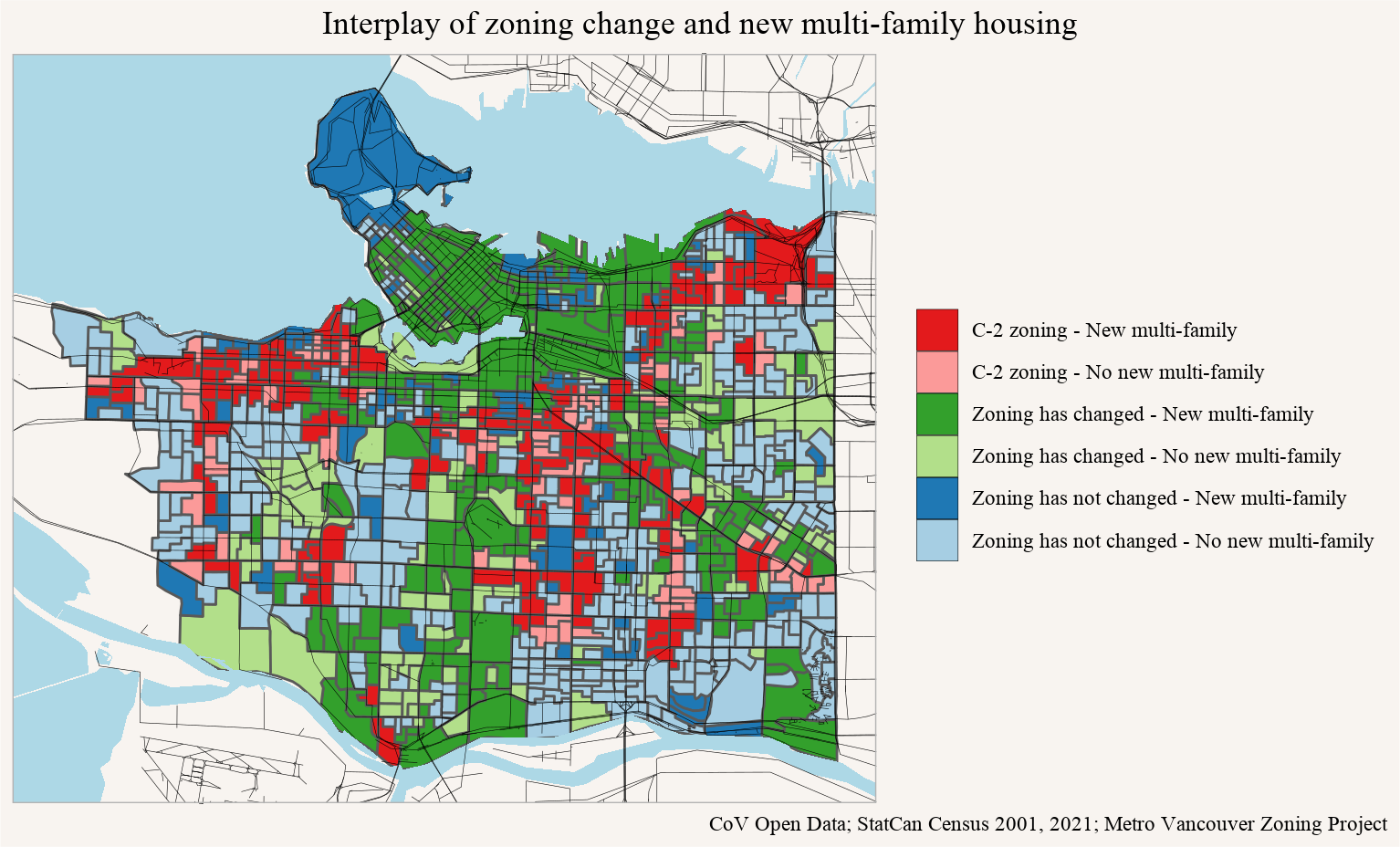

Visual inspection suggests that the change in children map lines up quite well with the change in zoning or the new multi-family building maps. Time to quantify this a little more. As a first step we can take the zoning map and new multi-family buildings map to label each census area in the change of children map by whether parts of it saw a zoning change or new multi-family developments. This process labels the dissemination areas in Vancouver as follows.

Comparing to the previous to maps we note that the areas don’t resemble the zoning changes or new developments in great detail, they are much larger. But those are the regions we are dealt by the census, and they can’t be changed without going through the work of pulling custom tabulations. But this should be good enough to give us a rough idea, we can use these labels to group the regions and count up the change in children in each group.

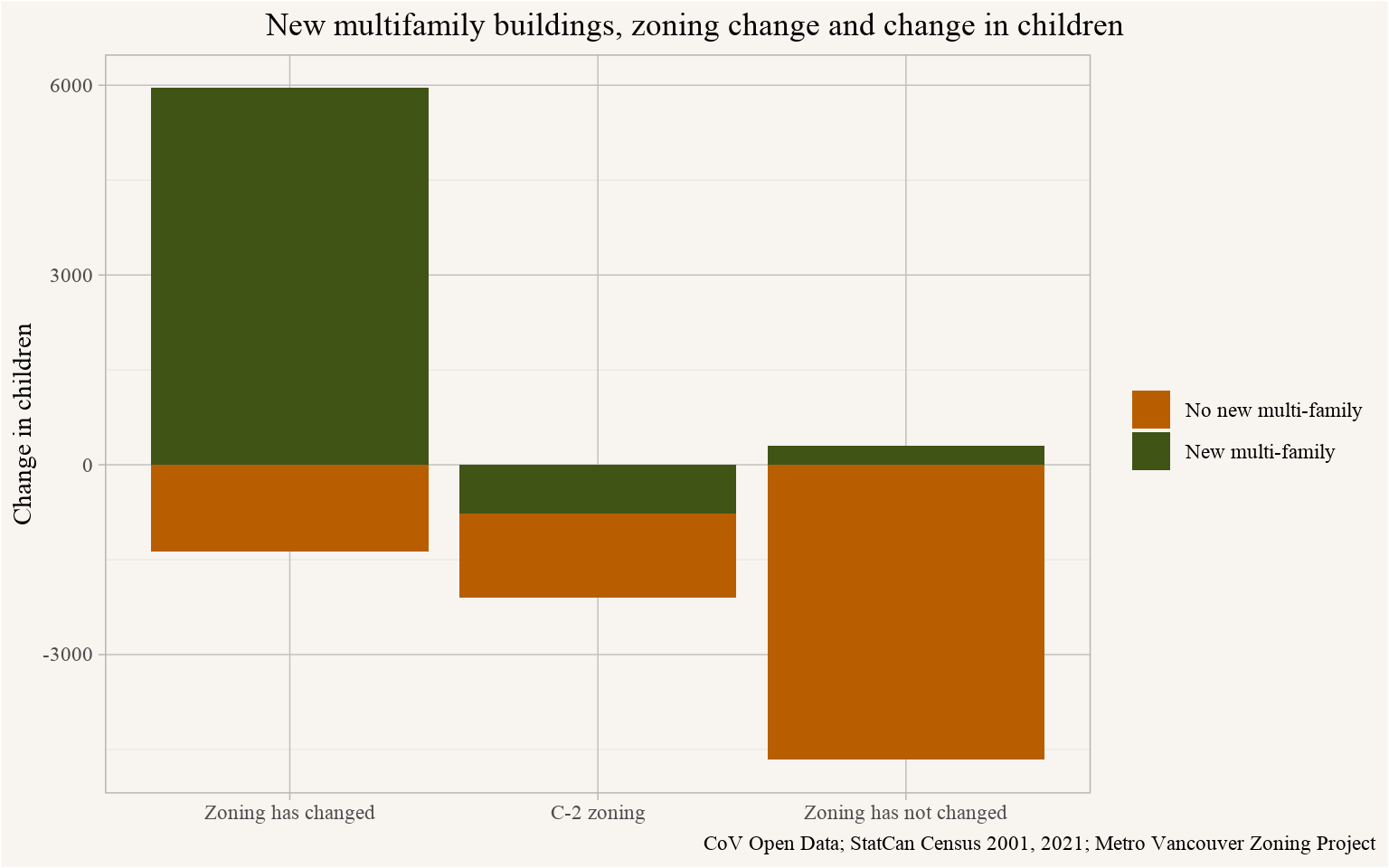

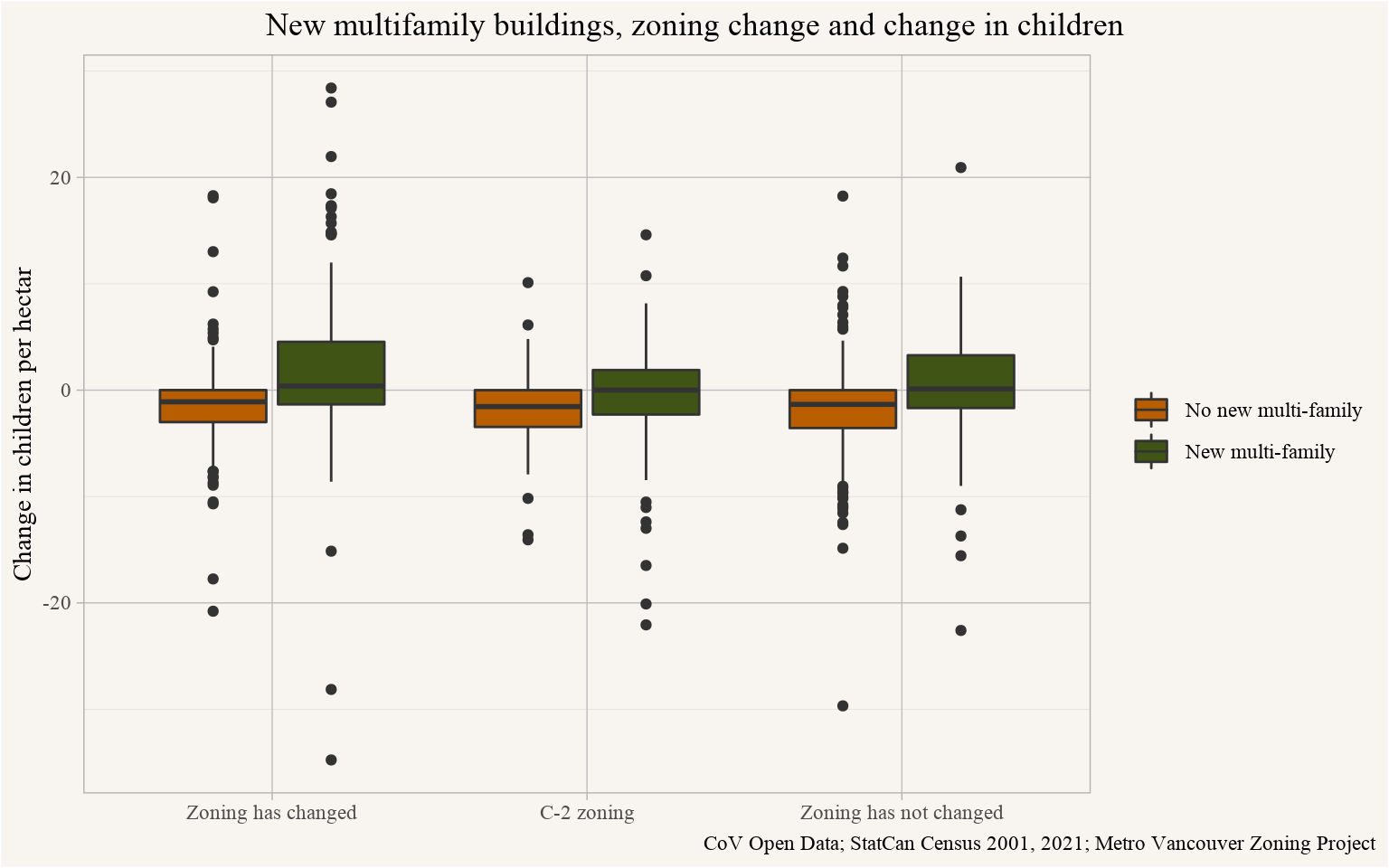

This suggests that, using our categories, Vancouver adds children primarily via rezonings, and while conditional C-2 zoning may generate new multi-family housing, it does not seem to add children. This is worth investigating a little further, there is the same data as boxplot normalized by area of each dissemination area.

Here C-2 comes out much more ambiguous, with some area containing C-2 zoning gaining children and some dropping children. Typically C-2 areas will only make up small parts of dissemination blocks, with the surrounding areas adding on their own loss or gain of children, which is probably closer to what we see in C-2 areas that have not seen new multi-family development, which on average amounted to a loss in children.

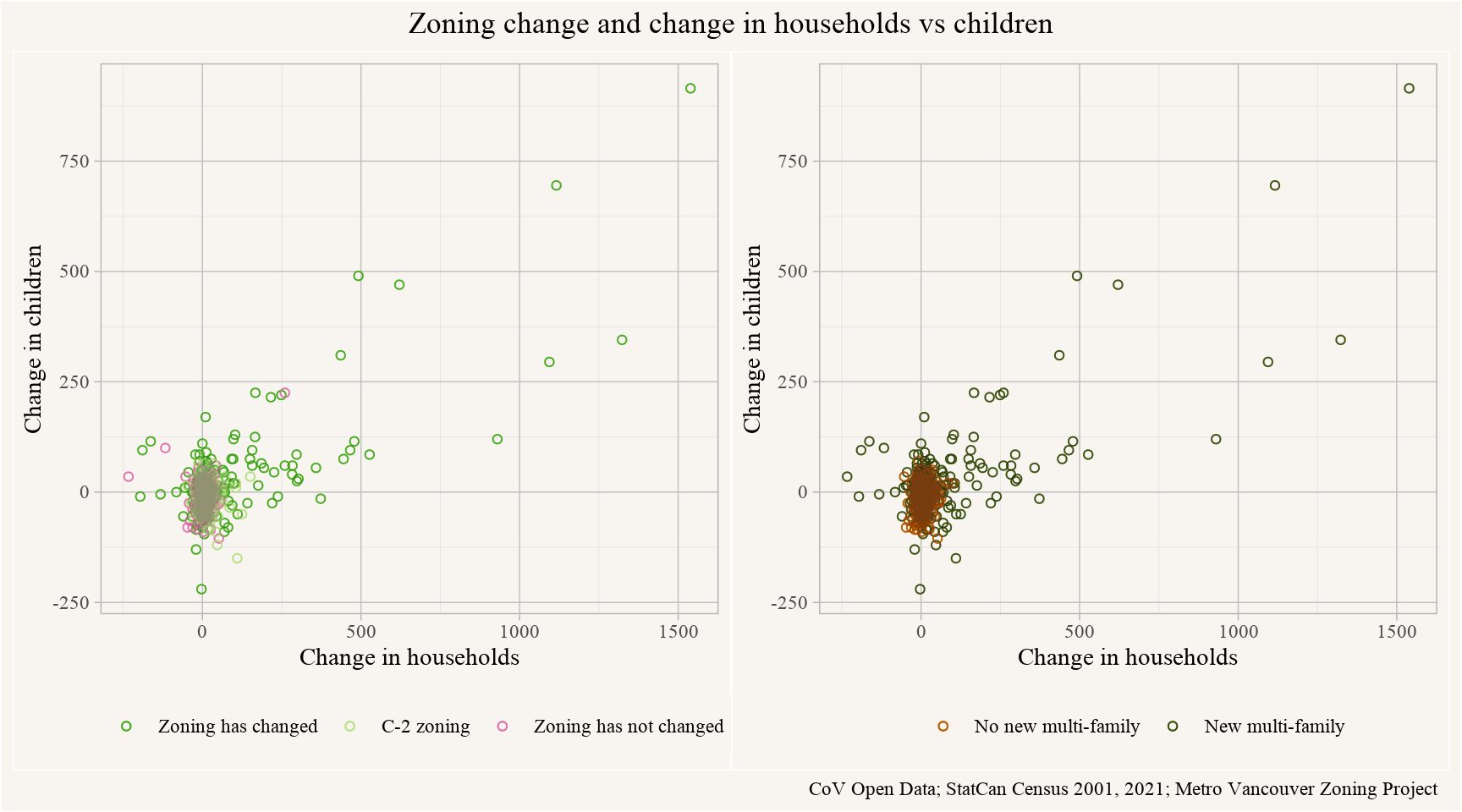

The census also has information on the number of households in each region, so we can compare the change in households to the change in children, coloured by the presence of zoning change (or new multi-family housing) in each region.

This again shows that children generally scale with the number of households. Fitting a linear model that also includes the starting number of children in each region we get that by 2021 each region roughly lost 21% of their 2001 children, offset by gaining 0.42 per net new household gained 2001-2021, explaining about 57% of the variation.

Upshot

Cities are changing. No matter if their physical form changes or not. City councillors and city planners direct how change in the city happens. There are many competing priorities of how we want our city to change, in this post we are singularly focused on understanding change in terms of the population of children under 15 years old.

Taking this as a metric, council and planners have steered most of the city into decline and funnelled all growth in children into small areas where they allowed new multi-family development that adds enough housing to counter-act the decline elsewhere in the city.

City-wide the decline has been small with children under 15 dropping 99%, but the geographic disparities had ripple effects throughout the city with school enrolment dropping in declining neighbourhoods contrasted by overfull schools and pressure on amenities in the growing parts. This trend and the mechanisms behind it have been clear for a long time now, yet council and planners have actively designed Vancouver to grow slower than the overall region, making the city increasingly exclusive, with the predictable consequence of squeezing out families with children.

Over the years councils have introduced several measures aimed to counter-act these trends. The legalization of secondary suites, the introduction of laneway houses and legalization of duplex fall into this category. But these efforts were too timid to halt the decline of children in the low-density neighbourhoods, with council making compromises like forcing laneway homes to be unnecessarily small, and reducing the overall floor space a duplex can achieve in order to limit uptake to appease voices that were more concerned about “neighbourhood character” than about declining children.

Other measures include mandated minimum shares of two and three bedroom units in multi-family developments, which led to an increase in children in areas where new multi-family housing was allowed. And at the same time produced the geographic disparities that created challenges for many families in the city.

Just to be clear, there is nothing special about the the development being multi-family vs single family in order to add children, other than multi-family developments are the only way Vancouver has added significant amounts of housing. Adding single-family housing would also work, except we haven’t, on net, done that in significant ways. Focusing on adding multi-family housing concentrated in a few select areas of the city, as Vancouver is done, is of course a choice. A different option would be to reduce minimum lot and frontage requirements and allow higher FSR to densify single-family areas with denser freehold housing, or with six-plexes as has been proposed by the mayor, maybe sprinkled with low-rise apartment buildings when the opportunity arises. But this would have to be done in a way that allows for faster change than what we have seen with suites, laneways and duplexes. And it remains to be seen if Vancouver is courageous enough to embrace families over their fear of change in low-density areas.

As usual, the code for this post is available on GitHub for anyone to reproduce or adapt.

Reproducibility receipt

## [1] "2022-05-11 18:09:59 PDT"## Local: master /Users/jens/Documents/R/mountaindoodles

## Remote: master @ origin (https://github.com/mountainMath/doodles.git)

## Head: [29c1196] 2022-05-12: children are good## R version 4.2.0 (2022-04-22)

## Platform: aarch64-apple-darwin20 (64-bit)

## Running under: macOS Monterey 12.3.1

##

## Matrix products: default

## BLAS: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRblas.0.dylib

## LAPACK: /Library/Frameworks/R.framework/Versions/4.2-arm64/Resources/lib/libRlapack.dylib

##

## locale:

## [1] en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8/C/en_CA.UTF-8/en_CA.UTF-8

##

## attached base packages:

## [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

##

## other attached packages:

## [1] cansim_0.3.11 patchwork_1.1.1

## [3] sf_1.0-7 cancensus_0.5.1

## [5] tongfen_0.3.5 mountainmathHelpers_0.1.4

## [7] forcats_0.5.1 stringr_1.4.0

## [9] dplyr_1.0.8 purrr_0.3.4

## [11] readr_2.1.2 tidyr_1.2.0

## [13] tibble_3.1.7 ggplot2_3.3.6

## [15] tidyverse_1.3.1

##

## loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

## [1] httr_1.4.2 sass_0.4.1 bit64_4.0.5 vroom_1.5.7

## [5] jsonlite_1.8.0 modelr_0.1.8 bslib_0.3.1 assertthat_0.2.1

## [9] cellranger_1.1.0 yaml_2.3.5 pillar_1.7.0 backports_1.4.1

## [13] glue_1.6.2 digest_0.6.29 rvest_1.0.2 colorspace_2.0-3

## [17] htmltools_0.5.2 pkgconfig_2.0.3 broom_0.8.0 haven_2.5.0

## [21] bookdown_0.26 scales_1.2.0 tzdb_0.3.0 git2r_0.30.1

## [25] proxy_0.4-26 generics_0.1.2 ellipsis_0.3.2 withr_2.5.0

## [29] cli_3.3.0 magrittr_2.0.3 crayon_1.5.1 readxl_1.4.0

## [33] evaluate_0.15 fs_1.5.2 fansi_1.0.3 xml2_1.3.3

## [37] class_7.3-20 geojsonsf_2.0.2 blogdown_1.9 tools_4.2.0

## [41] hms_1.1.1 lifecycle_1.0.1 munsell_0.5.0 reprex_2.0.1

## [45] compiler_4.2.0 jquerylib_0.1.4 e1071_1.7-9 rlang_1.0.2

## [49] classInt_0.4-3 units_0.8-0 grid_4.2.0 rstudioapi_0.13

## [53] rmarkdown_2.13 gtable_0.3.0 DBI_1.1.2 curl_4.3.2

## [57] R6_2.5.1 lubridate_1.8.0 knitr_1.38 fastmap_1.1.0

## [61] bit_4.0.4 utf8_1.2.2 KernSmooth_2.23-20 stringi_1.7.6

## [65] parallel_4.2.0 Rcpp_1.0.8.3 vctrs_0.4.1 dbplyr_2.1.1

## [69] tidyselect_1.1.2 xfun_0.30Reuse

Citation

@misc{children-are-good-actually.2022,

author = {{von Bergmann}, Jens},

title = {Children Are Good, Actually},

date = {2022-05-11},

url = {https://doodles.mountainmath.ca/posts/2022-05-11-children-are-good-actually/},

langid = {en}

}